Local anesthetic nerve block

Local anesthetic nerve block (local anesthetic regional nerve blockade, or often simply nerve block) is a short-term nerve block involving the injection of local anesthetic as close to the nerve as possible for pain relief. The local anesthetic bathes the nerve and numbs the area of the body that is innervated by that nerve. The goal of the nerve block is to prevent pain by blocking the transmission of pain signals from the surgical site. The block provides pain relief during and after the surgery. The advantages of nerve blocks over general anesthesia include faster recovery, monitored anesthesia care vs. intubation with an airway tube, and much less postoperative pain.[1]

There are various types of nerve blocks currently performed. Therapeutic blocks may be used for acute pain patients, diagnostic blocks are used to find pain sources, prognostic blocks are used to determine subsequent pain management options, preemptive blocks minimize postoperative pain, and some blocks can be used in place of surgery.[2] Certain surgeries may benefit from placing a catheter that stays in place for 2–3 days postoperatively. Catheters are indicated for some surgeries where the expected postoperative pain lasts longer than 15–20 hours. Pain medication can be injected through the catheter to prevent a spike in pain when the initial block wears off.[3]

The duration of the nerve block depends on the type of local anesthetics used and the amount injected around the target nerve. There are short acting (45–90 minutes), intermediate duration (90–180 minutes), and long acting anesthetics (4–18 hours). Block duration can be prolonged with use of a vasoconstrictor such as epinephrine, which decreases the diffusion of the anesthetic away from the nerve.[3]

Local anesthetic nerve blocks are sterile procedures that can be performed with the help of ultrasound, fluoroscopy (a live X-ray), or CT. Use of any one of these imaging modalities enables the physician to view the placement of the needle. Electrical stimulation can also provide feedback on the proximity of the needle to the target nerve.[3]

Mechanism of action

Local anesthetics act on the voltage-gated sodium channels that conduct electrical impulses and mediate fast depolarization along nerves.[4] They target open channels, bind on the inner side of the nerve membrane, and prevent ion flow.[5] The duration of the block is mostly influenced by the amount of time the anesthetic is near the nerve. Lipid solubility, blood flow in the tissue, and presence of vasoconstrictors with the anesthetic all play a role in this.[3] A higher lipid solubility makes the anesthetic more potent and have a longer duration of action; however, it also increases the toxicity of the drug.[3]

Toxicity and nerve injury

Local anesthetic toxicity is indicated by numbness and tingling around the mouth, metallic taste, or ringing in the ears. Additionally, this may lead to seizures, arrhythmias, and may progress to cardiac arrest. This reaction may stem from an allergy, excessive dose, or intravascular injection.[6] Other complications include nerve injury which has an extremely low rate of 0.029-0.2%.[7] Some research even suggests that ultrasound lowers the risk to 0.0037%.[7] The use of ultrasound and nerve stimulation has greatly improved practitioners’ ability to safely administer nerve blocks. Nerve injury most often occurs from ischaemia, compression, direct neurotoxicity, or needle laceration, and inflammation.[7]

Common local anesthetics and adjuvants

Local anesthetics are broken down into 2 categories: ester-linked and amide-linked drugs. The esters include benzocaine, procaine, tetracaine, and chloroprocaine. The amides include lidocaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine, bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and levobupivacaine. Chloroprocaine is a short-acting drug (45–90 minutes), lidocaine and mepivacaine are intermediate duration (90–180 minutes), and bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine are long-acting (4–18 hours).[3] Drugs commonly used for peripheral nerve blocks include lidocaine, ropivacaine, bupivacaine, and mepivacaine.[6] These drugs are often combined with adjuvants with the end goal of increasing the duration of the analgesia or shortening time of onset. Additives may include epinephrine, clonidine, and dexmedetomidine. Vasoconstriction caused by local anesthetic may be further enhanced synergistically with the addition of epinephrine, the most widely used additive. Epinephrine increases the length of analgesic duration and decreases blood flow by acting as an agonist at the α1-adrenoceptor. Use of epinephrine is controversial due to its potential neurotoxicity but is a valuable biomarker for intravascular injection. It is recommended that epinephrine be used only with nerve blocks performed without ultrasound guidance . Dexmedetomidine is not as widely used as epinephrine. Studies in humans indicate improved onset time and increased duration of analgesia.[8]

Upper Extremity Nerve Blocks

The brachial plexus is a bundle of nerves innervating the shoulder and arm and can be blocked at different levels depending on the type of upper extremity surgery being performed. Interscalene brachial plexus blocks can be done before shoulder, arm, and elbow surgery.[9] It is done at the neck where the brachial plexus emerges between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. Lidocaine is injected first to numb the skin and then a blunt needle is used to protect the nerves from damage as the physician places the needle very close to the nerves. The needle goes in about 3–4 cm and a single shot of local anesthetic is injected or a catheter is placed.[9] There is a very high chance that the phrenic nerve, which innervates the diaphragm, will be blocked so this block should only be done on patients who have use of their accessory respiratory muscles.[9] The block may not block the C8 and T1 roots which supply part of the hand, so it is usually not done for hand surgeries.[9] The supraclavicular and infraclavicular blocks can be performed for surgeries on the humerus, elbow, and hand.[10] These blocks are indicated for the same surgeries but they provide different views of the nerves, so it depends on the individual patient's anatomy to determine which block should be performed. A pneumothorax is a risk with these blocks, so the pleura should be checked with ultrasound to make sure the lung was not punctured during the block.[10] The axillary block is indicated for elbow, forearm, and hand surgery.[10]

Lower Extremity Nerve Blocks

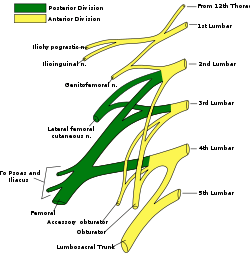

The femoral nerve block is indicated for femur, anterior thigh, and knee surgery.[11] It is performed slightly inferior to the inguinal ligament, and the nerve is under the fascia iliaca.[11] The sciatic nerve block is done for surgeries at or below the knee.[10] The nerve is located in the gluteus maximus muscle.[11] The popliteal block is done for ankle, achilles tendon, and foot surgery. It is done above the knee on the [11] posterior leg where the sciatic nerve starts splitting into the common peroneal and tibial nerves.[11] The saphenous nerve block is often done in combination with the popliteal block for surgeries below the knee.[11] The saphenous nerve is numbed at the medial part of the lower thigh under the sartorius muscle.[11] The lumbar plexus block is an advanced technique indicated for hip, anterior thigh, and knee surgery.[12] The lumbar plexus is composed of nerves originating from L1 to L4 spinal roots such as the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, femoral, and obturator nerves.[12] Since the plexus is located deep, there is an increased risk of local anesthetic toxicity, so less toxic anesthetics like chloroprocaine or mepivacaine mixed with ropivacaine are often recommended.[12] A curvilinear ultrasound probe can be used but it is often difficult to see the plexus, so a nerve stimulator is used to locate it.[13]

Paravertebral Nerve Block

The paravertebral block is versatile and can be used for various surgeries depending on the vertebral level it is done. A block at the neck in the cervical region is useful for thyroid gland and carotid artery surgery.[14] At the chest and abdomen in the thoracic region, blocks are used for breast, thoracic, and abdominal surgery.[14] A block at the hip in the lumbar region is indicated for hip, knee, and anterior thigh surgeries.[14] The paravertebral block provides unilateral analgesia, but bilateral blocks can be performed for abdominal surgeries.[15] Since it is a unilateral block, it may be chosen over epidurals for patients who can't tolerate the hypotension that follows bilateral sympathectomy.[15] The paravertebral space is located a couple centimeters lateral to the spinous process and is bounded posteriorly by the superior costotransverse ligament and anteriorly by the parietal pleura.[15] Complications include pneumothorax, vascular puncture, hypotension, and pleural puncture.[15]

References

- ↑ "About Regional Anesthesia / Nerve Blocks". UC San Diego Health. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ↑ Derrer, David T. "Pain Management and Nerve Blocks". WebMD. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gadsden, Jeff. "Local Anesthetics: Clinical Pharmacology and Rational Selection". NYSORA. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ↑ Marban E, Yamagishi T, Tomaselli GF (1998). "Structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels". The Journal of Physiology. 508 (3): 647–57. PMC 2230911

. PMID 9518722. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.647bp.x.

. PMID 9518722. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.647bp.x. - ↑ Strichartz G (1976). "Molecular mechanisms of nerve block by local anesthetics". Anesthesiology. 45 (4): 421–41. PMID 9844. doi:10.1097/00000542-197610000-00012.

- 1 2 "Common Regional Nerve Blocks" (PDF). UWHC Acute Pain Service. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 David Hardman. "Nerve Injury After Peripheral Nerve Block: Best Practices and Medical-Legal Protection Strategies". Anesthesiology News. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ Brummett CM, Williams BA (2011). "Additives to local anesthetics for peripheral nerve blockade". International Anesthesiology Clinics. 49 (4): 104–16. PMC 3427651

. PMID 21956081. doi:10.1097/AIA.0b013e31820e4a49.

. PMID 21956081. doi:10.1097/AIA.0b013e31820e4a49. - 1 2 3 4 "Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block". NYSORA. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Upper Extremity Nerve Blocks" (PDF). NYSORA. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Lower Extremity Nerve Blocks" (PDF). NYSORA. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Lumbar Plexus Block". NYSORA. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ "Lumbar plexus block:". Cambridge. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Regional anesthesia for surgery". ASRA. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Scott W Byram. "Paravertebral Nerve Block". Medscape. Retrieved 4 August 2017.