Saint George and the Dragon

The episode Saint George and the Dragon appended to the hagiography of Saint George was Eastern in origin, brought back with the Crusaders and retold with the courtly appurtenances belonging to the genre of Romance.[1] The earliest known depictions of the motif are from 10th- or 11th-century Cappadocia[2] and 11th-century Georgia;[3] while the veneration of Saint George as a soldier saint goes back to the 7th century at least, the earliest known surviving narrative of the dragon episode is an 11th-century Georgian text.[4]

In Western tradition, the dragon was combined with the already standardised Passio Georgii in the second half of the 13th century, first in Vincent of Beauvais' encyclopedic Speculum Historiale and Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend (1260s), rising to great popularity as a literary and pictorial subject in the Late Middle Ages.[5] The legend gradually became part of the Christian traditions relating to Saint George and was used in many festivals thereafter.[6]

Legend

According to the Golden Legend, the narrative episode of Saint George and the Dragon took place somewhere he called "Silene", in Libya; the Golden Legend is the first to place this story in Libya. In the tenth-century Georgian narrative, the place is the city of Lasia, and the idolatrous emperor who rules the city is called Selinus.[7]

The town had a small lake with a plague-bearing dragon living in it and poisoning the countryside. To appease the dragon, the people of Silene fed it two sheep every day. When they ran out of sheep they started feeding it their children, chosen by lottery. One time the lot fell on the king's daughter.[8] The king, in his grief, told the people they could have all his gold and silver and half of his kingdom if his daughter were spared; the people refused. The daughter was sent out to the lake, dressed as a bride, to be fed to the dragon.[7]

Saint George by chance rode past the lake. The princess tried to send him away, but he vowed to remain. The dragon emerged from the lake while they were conversing. Saint George made the Sign of the Cross and charged it on horseback, seriously wounding it with his lance. He then called to the princess to throw him her girdle, and he put it around the dragon's neck. When she did so, the dragon followed the girl like a meek beast on a leash.

The princess and Saint George led the dragon back to the city of Silene, where it terrified the populace. Saint George offered to kill the dragon if they consented to become Christians and be baptised. Fifteen thousand men including the king of Silene converted to Christianity. George then killed the dragon, and the body was carted out of the city on four ox-carts. The king built a church to the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint George on the site where the dragon died and a spring flowed from its altar with water that cured all disease.[9]

Iconography

Iconography of the horseman with spear overcoming evil was widespread throughout the Christian period.[10] In Pharaonic mythology, the god Setekh murdered his brother Osiris. Horus, the son of Osiris, avenged his father's death by killing Setekh. French researchers at the Louvre interpret a fourth century AD Coptic stone fenestrella of mounted hawk-headed figure (inferred as Horus) fighting a crocodile as Horus killing a metamorphorsed Setekh.[11] The linguistic similarity of George and Horus leads them to postulate the identity of the two characters.

Medieval iconography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Icons of Saint George and the Dragon. |

- Eastern

Some icons depicting the saint as a horseman killing the dragon date to the 12th century. Older (11th-century) icons from Georgia (Labechina, Ipari) show George as a horseman slaying a human enemy rather than a dragon. The motif becomes popular especially in Georgian and Russian tradition, but it is also found in Greek icons (where the earlier mode of depiction of George as a soldier on foot and without the dragon remains more common). The saint is depicted in the style of a Roman cavalryman in the tradition of the "Thracian Heros".

In Russian tradition, the icon is known as Чудо Георгия о змие, i.e. "the miracle of George and the dragon". The saint is mostly shown on a white horse, facing right, but sometimes also on a black horse, or facing left.[12] The princess is usually not included. Some icons show George killing the dragon on foot. Another motif shows George on horseback with the youth of Mytilene sitting behind him.

St George of Labechina (11th century), Racha, Georgia

St George of Labechina (11th century), Racha, Georgia Icon of St. George from Likhauri (Ozurgeti Municipality), Georgia (12th century?)

Icon of St. George from Likhauri (Ozurgeti Municipality), Georgia (12th century?) 12th century Byzantine depiction of Saint George and the Dragon (steatite)

12th century Byzantine depiction of Saint George and the Dragon (steatite).jpg) 14th-century icon from Novgorod

14th-century icon from Novgorod 14th-century icon from Rostov

14th-century icon from Rostov.jpg) A 15th-century Georgian cloisonné enamel icon

A 15th-century Georgian cloisonné enamel icon_by_shakko_01.jpg) 15th-century wooden sculpture from Rostov

15th-century wooden sculpture from Rostov

Icons of Saint George killing the dragon on foot:

15th-century Greek icon of Saint George killing the dragon on foot.

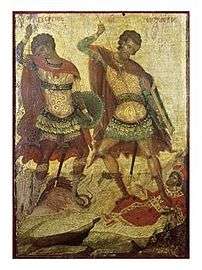

15th-century Greek icon of Saint George killing the dragon on foot. Michael Damaskinos (16th century), Saint George killing the dragon, alongside Saint Demetrios killing Kaloyan.

Michael Damaskinos (16th century), Saint George killing the dragon, alongside Saint Demetrios killing Kaloyan.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint George and the Dragon in medieval miniature. |

- Western

The motif of Saint George as a knight on horseback slaying the dragon first appears in western art in the second half of the 13th century. The tradition of the saint's arms being shown as the red-on-white St. George's Cross develops in the 14th century.

Miniature from a Passio Sancti Georgii manuscript (Verona, second half of 13th century)

Miniature from a Passio Sancti Georgii manuscript (Verona, second half of 13th century) Miniature from a manuscript of Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1348.

Miniature from a manuscript of Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1348. Book of Hours (c. 1380?).

Book of Hours (c. 1380?). Miniature from a manuscript of Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1382.

Miniature from a manuscript of Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1382. De Grey Hours (c. 1400)

De Grey Hours (c. 1400) Miniature from Heures de Charles d'Angoulême, Cognac, France, f.53v (1475–1500)

Miniature from Heures de Charles d'Angoulême, Cognac, France, f.53v (1475–1500)

Renaissance

- Paolo Uccello, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1470. National Gallery, London.

- Giovanni Bellini, Saint George Fighting the Dragon, c. 1471. Pesaro altarpiece.[13]

- Lieven van Lathem, Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1471)

- Bernt Notke, Saint George and the Dragon, Storkyrkan in Stockholm, ca. 1484–1489.[14]

- Andrea della Robbia, terracotta, c. 1490

- Albrecht Dürer, woodcut, 1501/4

- Raphael (Raffaello Santi), St. George, 1504. Oil on wood. Louvre, Paris, France.

- Raphael (Raffaello Santi), St. George and the Dragon, 1504–1506. Oil on wood. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States

- Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), Saint George and the Dragon, 1555.[15]

Bernat Martorell - Saint George Killing the Dragon (1435)

Bernat Martorell - Saint George Killing the Dragon (1435).jpg)

.jpg) Woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1501/4).

Woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1501/4).- St. George on Horseback, Meister des Döbelner Hochaltars, 1511/13, Hamburger Kunsthalle

- Woodcut frontispiece of Alexander Barclay, Lyfe of Seynt George (Westminster, 1515).

Early modern and modern art

Paintings

- Peter Paul Rubens, Saint George and the Dragon, 1620.

- Salvator Rosa, San Giorgio e il Drago

- Mattia Preti, St George triumphant over the dragon, 1678, at St. George's Basilica, Malta in Victoria Gozo.

- Edward Burne-Jones, St. George and the Dragon, 1866.[16]

- Gustave Moreau, St. George and the Dragon, c. 1870. Oil on canvas. The National Gallery, London.

- Briton Rivière, St. George and the Dragon, c. 1914.

- Uroš Predić, St George Killing the Dragon, 1930

Sculptures

- The sculptures which form part of the clock of Liberty's store in Regent Street, London (19th century).[17]

- Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, Saint George and the Dragon, bronze, State Library of Victoria, 1889[18]

- Salvador Dalí, Saint George and the Dragon, Open Air Museum in Cosenza, 1947

Mosaic

- Edward Poynter, Saint George for England, 1869. Central Lobby in the Palace of Westminster.

Engravings

- Benedetto Pistrucci, engraving for coin dies, 1817.

Prints

- On banknotes issued by the Bank of England:

Unknown painter from Ukraine, 18th century

Unknown painter from Ukraine, 18th century Pendant with Saint George by Lluís Masriera i Rosés (1902), Barcelona

Pendant with Saint George by Lluís Masriera i Rosés (1902), Barcelona St. George and the Dragon by Briton Reviere (c. 1914)

St. George and the Dragon by Briton Reviere (c. 1914) 1914 sovereign with Benedetto Pistrucci's engraving

1914 sovereign with Benedetto Pistrucci's engraving Reverse of an English £1 note of 1940

Reverse of an English £1 note of 1940 WWI British recruitment poster

WWI British recruitment poster

Coats of arms

- Austria: Pitten, Sankt Georgen an der Gusen, Sankt Georgen an der Leys, Sankt Georgen an der Stiefing, Sankt Georgen im Attergau, Sankt Georgen ob Murau.

- Croatia: Kaštel Sućurac.

- Czech Republic: Brušperk.

- Denmark: Holstebro.

- France: Aydoilles, Couilly-Pont-aux-Dames, Ligsdorf, Maulan, Mussidan, Saint-Georges (Moselle), Saint-Georges-Armont, Saint-Georges-d'Espéranche, Saint-Georges-d'Oléron, Saint-Georges-d'Orques, Saint-Georges-de-Reintembault, Saint-Georges-du-Bois, Saint-Georges-du-Vièvre, Saint-Georges-sur-Baulche, Saint-Georges-sur-Loire, Saint-Jurs, Saorge, Sospel, Villeneuve-Saint-Georges.

- Georgia.

- Germany: Bürgel, Hattingen, Mansfeld, Rittersbach, St. Georgen im Schwarzwald, Schwarzenberg.

- Hungary: Bácsszentgyörgy, Balatonszentgyörgy, Borsodszentgyörgy, Dunaszentgyörgy, Homokszentgyörgy, Pécsvárad, Szentgyörgyvár, Szentgyörgyvölgy, Tatárszentgyörgy.

- Italy: Reggio Calabria.

- Lithuania: Marijampolė, Prienai, Varniai.

- Netherlands: Ridderkerk, Terborg.

- Poland: Brzeg Dolny, Dzierżoniów, Milicz.

- Romania: Suceava, Sfântu Gheorghe.

- Russia: Moscow, Moscow Oblast.

- Serbia: Srpski Krstur.

- Slovakia: Svätý Jur.

- Spain: Alcalá de los Gazules, Golosalvo, Puentedura.

- Switzerland: Castiel, Kaltbrunn, Ruschein, Saint-George, Schlans, Stein am Rhein, Waltensburg/Vuorz.

- Ukraine: Kiev Oblast, Liuboml, Nizhyn, Taikury, Volodymyr-Volynskyi.

Coat of arms of Marijampolė, Lithuania

Coat of arms of Marijampolė, Lithuania Standard of the President of Georgia

Standard of the President of Georgia

Literary references and popular culture

- William Shakespeare refers to Saint George and the Dragon in Richard III ( Advance our standards, set upon our foes Our ancient world of courage fair St. George Inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons act V, sc. 3) also in King Lear (act I).

- Edward Elgar, The Banner of St George: a ballad for chorus and orchestra, words by Shapcott Wensley, 1879.

- A 17th-century broadside ballad paid homage to the feat of George's dragon slaying. Titled "St. George and the Dragon", the ballad considers the importance of Saint George in relation to other heroes of epic and Romance, ultimately concluding that all other heroes and figures of epic or romance pale in comparison to the feats of George.[20]

- The 1898 Dream Days by Kenneth Grahame includes a chapter entitled The Reluctant Dragon, in which an elderly Saint George and a benign dragon stage a mock battle to satisfy the townsfolk and get the dragon introduced into society. Later made into a film by Walt Disney Productions, and set to music by John Rutter as a children's operetta.

- In 1935 Stanley Holloway recorded a humorous retelling of the tale as St. George and the Dragon written by Weston and Lee.

- The Dragon Knight, a series of books by Gordon R. Dickson, adopted this story as a past event into its canon, significant in that dragons had since referred to humans as 'georges.' The story of Saint George and the Dragon is referred to on occasion, but never told. The first book in the series, The Dragon and the George, is a retelling of a previous short story by the same author, "St. Dragon and the George".

- In the 1950s, Stan Freberg and Daws Butler wrote and performed St. George and the Dragon-Net (a spoof of the tale and of Dragnet) for Freberg's radio show. The story's recording became the first comedy album to sell over a million copies.

- EC Comics published a comic called "By George!!" in Weird Fantasy #15 (1952). The story revealed that the 'dragon' was in fact a lost, misunderstood alien child who did not mean any harm.

- The poem "Fairy Tale" by Yury Zhivago–the main character from Boris Pasternak's novel Doctor Zhivago (1957)–relates a modified account of this legend; Yury's poem differs in that it is nonreligious and makes no mention of the village.

- The 1962 film The Magic Sword is loosely based on the legend.

- The 1968 children's book The Iron Man, by Ted Hughes, is a contemporary re-telling of the myth in which nature (the dragon, named the 'space-bat-angel-dragon' in the book) and man eventually work together symbiotically, creating harmony on Earth after the eponymous Iron Man defeats the beast in a contest of endurance.

- A 1975 episode of Space: 1999 titled "Dragon's Domain" made reference to the legend of Saint George and the Dragon. A crewman from the space station heroically kills a dragon-like creature after it has consumed other astronauts. The main character played by Barbara Bain eventually concludes that the crewman's story will create new mythology similar to the legend of Saint George.

- The 1981 Paramount Pictures/Disney film Dragonslayer was loosely based on the tale.[21]

- The story was referenced on the cover of the 1983 Bob Marley & The Wailers album Confrontation which shows a recently deceased Bob Marley in the place of Saint George.

- Margaret Hodges retold the legend in a 1984 children's book (Saint George and the Dragon) with Caldecott Medal-winning illustrations by Trina Schart Hyman.

- In Elizabeth Kostova's The Historian,[22] Saint George is chronicled as being the saint who killed Vlad Tepesh[23] (also known as Dracula, which means "son of the dragon" or "son of the devil").

- In Graham McNeill's Horus Heresy novel Mechanicum, Book 9 of the Horus Heresy book series, the story is retold and George is revealed to be the future Emperor of Mankind.[24]

- The animated series Ben 10: Ultimate Alien has "Sir George", a thousand year old immortal who slays an extra-dimensional dragon called "Diagon".

- In 2004, a made-for-TV movie alternatively titled Dragon Sword or George and the Dragon, starred James Purefoy and Piper Perabo.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Duncan Robertson, The Medieval Saints' Lives (1998), pp 51f. suggested that the dragon motif was transferred to the George legend from that of his father fellow soldier saint, Saint Theodore Tiro. The Roman Catholic writer Alban Butler (Lives of the Saints) was at pains to credit the motif as a late addition: "It should be noted, however, that the story of the dragon, though given so much prominence, was a later accretion, of which we have no sure traces before the twelfth century. This puts out of court the attempts made by many folklorists to present St. George as no more than a Christianized survival of pagan mythology." See also: 'To the Glory of St George' in: Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books.

- ↑ Walter 2003:128, noted by British Museum Russian Icon "The Miracle of St George and the Dragon / Black George".

- ↑ Christopher Walter, The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition 2003:141, notes the earliest datable image, at Pavnisi, Georgia (1154–58)

- ↑ Patriarchal Library, Jerusalem, codex 2, according to Christopher Walter, The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition 2003:140; Walter quotes the text at length, from a Russian translation.

- ↑ Margaret Aston, Faith and Fire Continuum Publishing, 1993 ISBN 1-85285-073-6 page 272

- ↑ Christian Roy, 2005, Traditional Festivals ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5 page 408; Dorothy Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe, (BiblioBazaar), 2008 ISBN 1-4375-2015-4, page 67

- 1 2 Quoted in Walter 2003:141.

- ↑ The Book of Saints and Heroes by Mrs. Lang

- ↑ Thus Jacobus de Voragine, in William Caxton's translation (On-line text).

- ↑ Charles Clermont-Ganneau, "Horus et Saint Georges, d’après un bas-relief inédit du Louvre". Revue archéologique, 1876

- ↑ "Horus on horseback | Louvre Museum | Paris". www.louvre.fr.

- ↑ notably the icon known as "Black George", showing the saint both on a black horse and facing left, made in Novgorod in the first half of the 15th century (BM 1986,0603.1)

- ↑ Archived February 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Nordisk familjebok. 1914.

- ↑ Archived September 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Burne-Jones, Sir Edward. "St. George and the Dragon". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ The Liberty Clock waymarking.com.

- ↑ "Forecourt Statues of The State Library of Victoria". THE GARGAREAN. WordPress.com. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "Withdrawn Banknotes: Reference Guide" (PDF). Bank of England. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ↑ "New Ballad of St. George and the Dragon (EBBA 34079)". English Broadside Ballad Archive. National Library of Scotland - Crawford 1349: University of California at Santa Barbara, Department of English. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ No Land is an Urland- The Creation of the World of Dragonslayer by Danny Fingeroth from Dragonslayer- The Official Marvel Comics Adaptation of the Spectacular Paramount/Disney Motion Picture!, Marvel Super Special Vol.1, No. 20, published by Marvel Comics Group, 1981

- ↑ The Historian

- ↑ Vlad tepes

- ↑ McNeill, Graham (2008). Mechanicum: war comes to Mars (mass market paperback) (print). Horus Heresy [book series]. 9. Cover art & illustration by Neil Roberts; map by Adrian Wood (1st UK ed.). Nottingham, UK: Black Library. pp. 212–215, 360–364. ISBN 978-1-84416-664-0.

References

- Loomis, C. Grant, 1949. White Magic, An Introduction to the Folklore of Christian Legend (Cambridge: Medieval Society of America)

- Whatley, E. Gordon, editor, with Anne B. Thompson and Robert K. Upchurch, 2004. St. George and the Dragon in the South English Legendary (East Midland Revision, c. 1400) Originally published in Saints' Lives in Middle English Collections (on-line text: Introduction).

- Catholic Encyclopedia, "Saint George"

- (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications) (On-line Introduction)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint George and the Dragon. |

- Saint George Legend explained in Javascript by Tomás Corral

- Saint George church in Dolinka (Hungarian: Inám)

- St George and the Dragon Events and Ideas – Official Website for Tourism in England

- St George Unofficial Bank Holiday: St. George and the Dragon, free illustrated book based on 'The Seven Champions' by Richard Johnson (1596)

- St George's Bake and Brew

- St. George Killing the Dragon: aromatic icon