Lublin

| Lublin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| |||

|

Motto: Fidelitatem et Constantinam (in Latin) Wiernością i Stałością (in Polish)[1] | |||

Lublin | |||

| Coordinates: 51°14′53″N 22°34′13″E / 51.24806°N 22.57028°ECoordinates: 51°14′53″N 22°34′13″E / 51.24806°N 22.57028°E | |||

| Country | Poland | ||

| Voivodeship | Lublin | ||

| County | city county | ||

| Established | before 12th century | ||

| Town rights | 1317 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Krzysztof Żuk | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 147 km2 (57 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2009) | |||

| • City | 349,103 | ||

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,200/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 664,000 | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 20-001 to 20-999 | ||

| Area code(s) | +48 81 | ||

| Car plates | LU | ||

| Website | http://www.um.lublin.pl/ http://www.lublin.eu/en | ||

Lublin [ˈlublʲin] (Latin: Lublinum; English: /ˈlʌblɪn/) is the ninth largest city in Poland and the second largest city of Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship (province) with a population of 349,103 (March 2011). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of the Vistula River, and is located approximately 170 kilometres (106 miles) to the southeast of Warsaw by road.

One of the events that greatly contributed to the city's development was the Polish-Lithuanian Union of Krewo in 1385. Lublin thrived as a centre of trade and commerce due to its strategic location on the route between Vilnius and Kraków; the inhabitants also had the privilege of free trade in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Lublin Parliament session of 1569 led to the creation of a real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, thus creating the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Lublin also witnessed the early stages of Reformation in the 16th century. A Calvinist congregation was founded and certain groups of radical Arians also appeared in the city, making it an important global centre of Arianism. At the turn of the centuries, Lublin was also recognized for hosting a number of outstanding poets, writers and historians of the epoch.[2]

Until the partitions at the end of the 18th century, Lublin was a royal city of the Crown Kingdom of Poland. Its delegates and nobles had the right to participate in the Royal Election. In 1578 Lublin was chosen as the seat of the Crown Tribunal, the highest appeal court in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and for centuries the city has been flourishing as a centre of culture and higher learning, together with Kraków, Warsaw, Poznań and Lwów.

Although Lublin was not spared from severe destruction during World War II, its picturesque and historical Old Town has been preserved. The district is one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomnik historii), as designated May 16, 2007, and tracked by the National Heritage Board of Poland.[3]

The city is viewed as an attractive location for foreign investment and the analytical Financial Times Group has found Lublin to be one of the best cities for business in Poland.[4] The Foreign direct investment ranking (FDI) placed Lublin second among larger Polish cities in the Cost-effectiveness category. Lublin is also noted for its green spaces and a high standard of living.[5]

History

Archaeological finds indicate a long presence of cultures in the area. A complex of settlements started to develop on the future site of Lublin and in its environs in the 6th-7th centuries. Remains of settlements dating back to the 6th century were discovered in the center of today's Lublin on Czwartek ("Thursday") Hill. The next period of the early Middle Ages was marked by intensification of habitation, particularly in the areas along river valleys. The settlements at the time were centered around the stronghold on Old Town Hill, which was likely one of the main centers of Lendians tribe. When the tribal stronghold was destroyed in the 10th century, the center shifted to the north-east, to a new stronghold above Czechówka valley, and after the mid-12th century to Castle Hill. At least two churches are presumed to have existed in Lublin in the early medieval period. One of them was most probably erected on Czwartek Hill during the rule of Casimir the Restorer in the 11th century.[6] The castle became the seat of a Castellan, first mentioned in historical sources from 1224, but quite possibly present from the start of the 12th or even 10th century. The oldest historical document mentioning Lublin dates from 1198, so the name must have come into general use some time earlier.[6]

The location of Lublin at the eastern borders of the Polish lands gave it military significance. During the first half of the 13th century, Lublin was a target of attacks by Mongols, Ruthenians and Lithuanians, which resulted in its destruction.[6] It was also ruled by Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia between 1289 and 1302.[6] Lublin was founded as a town by Władysław I the Elbow-high or between 1258 and 1279 during the rule of prince Bolesław V the Chaste.[6] Casimir III the Great, appreciating the site's strategic importance, built a masonry castle in 1341 and encircled the city with defensive walls.[7] From 1326, if not earlier, the stronghold on Castle Hill included a chapel in honor of the Holy Trinity. A stone church dated to the years 1335-1370 exists to this day.[6]

Jagiellonian Poland

In 1392, the city received an important trade privilege from king Władysław II Jagiełło, and with the coming of the peace between Poland and Lithuania developed into a trade centre, handling a large portion of commerce between the two countries. In 1474 the area around Lublin was carved out of Sandomierz Voivodeship and combined to form the Lublin Voivodeship, the third voivodeship of Lesser Poland. During the 15th century and 16th century the town grew rapidly. The largest trade fairs of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were held in Lublin. During the 16th century the noble parliaments (sejm) were held in Lublin several times. On 26 June 1569, one of the most important proclaimed the Union of Lublin, which united Poland and Lithuania. The Lithuanian name for the city is Liublinas. Lublin as one of the most influential cities[6] of the state enjoyed voting rights during the royal elections in Poland.

Some of the artists and writers of the 16th century Polish renaissance lived and worked in Lublin, including Sebastian Klonowic and Jan Kochanowski, who died in the city in 1584. In 1578 the Crown Tribunal, the highest court of the Lesser Poland region, was established in Lublin.[6]

Since the second half of the 16th century, Protestant Reformation movements devolved in Lublin, and a large congregation of Polish Brethren was present in the city. One of Poland's most important Jewish communities was also established in Lublin around this time.[6] Jews established a widely respected yeshiva, Jewish hospital, synagogue, cemetery and education centre (kahal) and built the Grodzka Gate (known as the Jewish Gate) in the historic district. Jews were a vital part of the city's life until the Holocaust, during which they were relocated to the infamous Lublin Ghetto and ultimately murdered.[6]

The yeshiva became a centre of learning of both Talmud and Kabbalah, leading the city to be called "the Jewish Oxford";[6] in 1567, the rosh yeshiva (headmaster) received the title of rector from the king along with rights and privileges equal to those of the heads of Polish universities.

In the 17th century, the town declined due to a Russo-Ukrainian invasion in 1655 and a Swedish invasion during the Northern Wars. After the third of the Partitions of Poland in 1795 Lublin was located in the Austrian empire, then since 1809 in the Duchy of Warsaw, and then since 1815 in the Congress Poland under Russian rule. At the beginning of the 19th century new squares, streets and public buildings were built. In 1877 a railway connection to Warsaw and Kovel and Lublin Station were constructed, spurring industrial development. Lublin's population grew from 28,900 in 1873 to 50,150 in 1897 (including 24,000 Jews).[8]

Russian rule ended in 1915, when the city was occupied by German and Austro-Hungarian armies. After the defeat of the Central Powers in 1918, the first government of independent Poland operated in Lublin for a short time. In the interwar years, the city continued to modernise and its population grew; important industrial enterprises were established, including the first aviation factory in Poland, the Plage i Laśkiewicz works, later nationalised as the LWS factory. The Catholic University of Lublin was founded in 1918.

World War II

After the 1939 German and Soviet invasion of Poland the city found itself in the General Government territory controlled by Nazi Germany. The population became a target of severe Nazi repressions focusing on Polish Jews. An attempt to "Germanise" the city led to an influx of the ethnic Volksdeutsche increasing the number of German minority from 10–15% in 1939 to 20–25%. Near Lublin, the so-called 'reservation' for the Jews was built based on the idea of racial segregation also known as the "Nisko or Lublin Plan".[9]

The Jewish population was forced into the newly set Lublin Ghetto near Podzamcze. The city served as headquarters for Operation Reinhardt, the main German effort to exterminate all Jews in occupied Poland. The majority of the ghetto inmates, about 26,000 people, were deported to the Bełżec extermination camp between 17 March and 11 April 1942. The remainder were moved to facilities around the Majdanek concentration camp established at the outskirts of the city. Almost all of Lublin's Jews were murdered during the Holocaust in Poland. After the war, some survivors emerged from hiding with the Christian rescuers or returned from the Soviet Union, and reestablished a small Jewish community in the city, but their numbers were insignificant. Most left Poland for Israel and the West.[10]

On 24 July 1944, the city was taken by the Soviet Army and became the temporary headquarters of the Soviet-controlled communist Polish Committee of National Liberation established by Joseph Stalin, which was to serve as basis for a puppet government. The capital of new Poland was moved to Warsaw in January 1945 after the Soviet westward offensive.

In the postwar years, Lublin continued to grow, tripling its population and greatly expanding its area. A considerable scientific and research base was established around the newly founded Maria Curie-Sklodowska University. A large Automobile Factory FSC was built in the city.

Climate

Lublin has a borderline humid continental climate (Köppen Cfb/Dfb) with cold, damp winters and warm summers.

| Climate data for Lublin (1936−2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

27.2 (81) |

35.7 (96.3) |

33.9 (93) |

35.0 (95) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.2 (91.8) |

25.0 (77) |

18.9 (66) |

15.0 (59) |

37.0 (98.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

0.8 (33.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

1.6 (34.9) |

7.8 (46) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −5.9 (21.4) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2 (28) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.0 (32) |

−3.9 (25) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.2 (−26) |

−31.1 (−24) |

−30.9 (−23.6) |

−7.2 (19) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

0.0 (32) |

2.0 (35.6) |

0.0 (32) |

−4 (25) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−17.9 (−0.2) |

−23.9 (−11) |

−32.2 (−26) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 22.7 (0.894) |

25.9 (1.02) |

27.3 (1.075) |

42.4 (1.669) |

51.1 (2.012) |

66.6 (2.622) |

71.5 (2.815) |

64.0 (2.52) |

55.5 (2.185) |

40.6 (1.598) |

36.7 (1.445) |

33.6 (1.323) |

537.9 (21.177) |

| Average precipitation days | 23.3 | 19.5 | 18.4 | 13.1 | 13.0 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 9.3 | 11.2 | 13.3 | 18.1 | 20.8 | 184.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88.7 | 85.9 | 79.8 | 68.9 | 71.9 | 73.7 | 75.1 | 74.4 | 79.8 | 84.0 | 89.4 | 90.2 | 80.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 53 | 73 | 115 | 174 | 226 | 237 | 238 | 248 | 165 | 124 | 48 | 37 | 1,738 |

| Source: Climatebase.ru[11] | |||||||||||||

Population

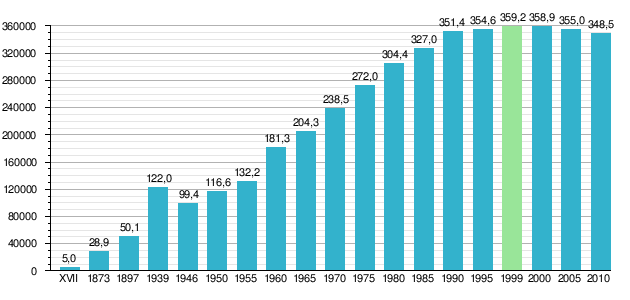

The diagram shows population growth over the past 400 years. As of 1999, the population of Lublin was estimated to 359,154, the highest in the city's history.

Economy

The Lublin region is a part of eastern Poland, which has benefited less from the economic transformation after 1989 than regions of Poland located closer to Western Europe. Despite the fact that Lublin is one of the closest neighbour cities for Warsaw, the investition inflow in services from Polish Capital has secured a steady growth due to relatively fast connection, while external investitions are progressing, enabling near-by satellite municipality Świdnik for large-scale industrial investitions, seamlessly testing the capacity of the agglomeration. The close cooperation with Warsaw is significant to the regional economy, also allows to bring quality cultural events inshore, and yet, the proximity of Warsaw is an underestimated asset.

Lublin is a regional center of IT companies. Asseco Business Solutions S.A., eLeader Sp z o.o., CompuGroup Medical Polska Sp. z o.o., Abak-Soft Sp. z o.o. and others have their headquarters there. Other companies (for example Comarch S.A., Britenet Sp. z o.o., Simple S.A., Asseco Poland S.A.) outsourced to Lublin, to take advantage of the educated specialists. There is a visible growth in number of professionals eager to work in Lublin, due to various reasons, like quality of life, culture management, the environment, improving connection to Warsaw, levels of education, or financial, because of usually higher operating margins of global organizations present in the area.

The large car factory FSC (Fabryka Samochodów Ciężarowych) seemed to have a brighter future when was acquired by the South Korean Daewoo conglomerate in the early 1990s. With Daewoo's financial troubles in 1998 related to the Asian financial crisis, the production at FSC practically collapsed and the factory entered bankruptcy.[6] Efforts to restart its van production succeeded when the engine supplier bought the company to keep its prime market.[6] With the decline of Lublin as a regional industrial centre, the city's economy has been reoriented towards the service industries. Currently, the largest employer is the Maria Curie-Sklodowska University (UMCS).

The price of land and investing costs are lower than in western Poland. However, the Lublin area has to be one of the main beneficiaries of the EU development funds.[12] Jerzy Kwiecinski, the deputy secretary of state in the Ministry for Regional Development at the Conference of the Ministry for Regional Development (Poland in the European Union — new possibilities for foreign investors) said:

In the immediate financial outlook, between 2007 and 2013, we will be the largest beneficiaries of the EU — every fifth Euro will be spent in Poland. In total, we will have at our disposal 120 billion EUR, assigned exclusively for post development activities. This sum will be an enormous boost for our country.[13]

In September 2007, the prime minister signed a bill creating a special economic investment zone in Lublin that offers tax incentives. It is part of “Park Mielec” — the European Economic Development area.[14] At least 13 large companies had declared their wish to invest here, e.g., Carrefour, Comarch, Safo, Asseco, Aliplast, Herbapol and Perła Browary Lubelskie.[15] At the same time, the energy giant Polska Grupa Energetyczna, which will build Poland's first nuclear power station, is to have its main offices in Lublin.

Modern shopping centers built in Lublin like Tarasy Zamkowe (Castle Terraces), Lublin Plaza, Galeria Olimp, Galeria Gala, the largest shopping mall in the city, covering 33,500 square meters of area. Similar investments are planned for the near future such as Park Felin (Felicity) and a new underground gallery ("Alchemy") between and beneath Świętoduska and Lubartowska Streets.[16]

Media

There is a public TV station in the city, called TVP Lublin which owns a 104-meter-tall concrete television tower.[17] The station put its first program on the air in 1985. In recent years it contributed programming to TVP3 channel and later TVP Info.

The radio stations airing from Lublin include Radio eR - 87.9 FM, Radio Eska Lublin - 103.6 FM, Radio Lublin (regional station of the Polish Radio) - 102.2 FM, [ Radio Centrum (university radio station)] - 98.2 FM, Radio Free (city station of the Polish Radio) - 89,9 FM, and Radio Złote Przeboje (Golden Hits) Lublin - 95.6 FM,

Local newspapers include: Kurier Lubelski daily, regional partner of the national newspaper Dziennik Wschodni daily, Gazeta Wyborcza [ Lublin Edition] daily (regional supplement to the national newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza), [ Metro] (daily, free) and Nasze Miasto Lublin weekly (free).

Transport

From Lublin railway station, ten trains depart each day to Warsaw, and three to Kraków, as in other major cities in Poland. Long-distance buses depart from near the Castle in the Old Town and serve most of the same destinations as the rail network. The express train to Warsaw takes about two and half hours.[18] The Lublin Airport is located in Świdnik, about 10 km (6.2 miles) SE of Lublin. There is a direct train link from the airport to downtown.

_Lichen99.jpg)

Roads

As of 2009 no motorways or expressways connect the city with the rest of Poland. In the coming decade the construction of expressways S12, S17 and S19 will improve road access to the city. On 17 December 2009 the bidding process for the construction of S17 expressway around Lublin was started. The construction began in 2010 and was completely finished in 2014. The project included a high capacity bypass road around Lublin, removing most of the through traffic from the city streets and decreasing congestion.

Lublin is one of only four towns in Poland to have trolleybuses (the others are Gdynia, Sopot and Tychy).[19]

Culture and tourism

Lublin is not only the largest city in eastern Poland, but also serves as an important regional cultural capital. Since then, many important international events have taken place here, involving Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Russian and Belarusian artists, researchers and politicians. The frescos at the Holy Trinity Chapel in Lublin Castle are a mixture of Catholic motifs with eastern Russian-Byzantine styles, reinforcing how the city connects the West with the East.

Museum

The premier museum in the city is the Lublin Museum, one of the oldest and largest museums of Eastern Poland, as well as the Majdanek State Museum with 121,404 visitors in 2011.[20]

Cinema

Lublin is a city with filmmaking past. A few important films were recorded here. e.g., Oscar-winning The Reader was partially filmed at the Nazi Majdanek concentration camp, located in boundaries of nowadays Lublin Area.[21]

In 2008, Lublin in cooperation with Ukrainian Lviv, filmed promotional materials, to promote them as cinematic cities. Films were handed out between filmmakers present at Cannes Festival.[22] Action, was sponsored by the European Union. There are a number of movie theaters in Lublin including Cinema City (multiplex), Cinema Bajka, Cinema Chatka Żaka, and Cinema Medyk.

Theatres

There are many cultural organizations in Lublin, either municipal, governmental and/or non-governmental. Among the popular venues are municipal theatres and playhouses such as:

- Musical Theatre in Lublin - Teatr Muzyczny w Lublinie, opera, operetta, musical, ballet

- Henryk Wieniawski Lublin Philharmonic - 'Filharmonia Lubelska

- Juliusz Osterwa Theatre in Lublin - Teatr im. Juliusza Osterwy w Lublinie]

- Hans Christian Andersen Theatre - with puppet programme for children

- Fringe theatres:

- Centrum Projekt Pracovnia Maat

- Centrum Kultury w Lublinie

- Ośrodek Praktyk Teatralnych – Gardzienice

- Ośrodek „Brama Grodzka - Theatre NN”

Galleries

There are numerous art galleries in Lublin; some are run by private owners, and some are municipal, government, NGO, or associations' venues. The Labyrinth Gallery, formerly "BWA", is the Artistic Exhibitions Office (Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych).

Old Town

Lublin, by some tourists can be called "a little Krakow", and this is true by the citizens sharing a number of Lesser Poland traditions, historic architecture and a unique ambiance, especially in the Old Town. Catering to students, who account for 35% of the population, the city offers a vibrant music and nightclub scene [23] Lublin has many theatres and museums and a professional orchestra, the Lublin Philharmonic.[24][25][26][27] Old buildings, even ruins, create magic and unique atmosphere of the renaissance city. Lublin’s Old Town has cobbled streets and traditional architecture. Many venues around Old Town enjoy an architecture applicable for restaurants, art galleries, clubs, apart from entertainment this area has also been designed to place small businesses and prestigious offices.

Pubs and restaurants

The Old Town Hall and Tribunal in the Market Square is surrounded by burgher houses and winding lanes.[28][29][30] In the Old Town and the immediate environs there are over 100 restaurants, cafes, pubs, clubs and other catering outlets, with cuisine of all kinds, ranging from haut cuisine to takeaways

City of festivals

_04.jpg)

.jpg)

Lublin would like to be known as "the Capital of Festivals".[6] Every year another new festival appears. The most significant of them include:

- Karnawał Sztuk-Mistrzów - Carnival Arts-Masters.

- Noc Kultury - Culture Night - usually the first Saturday night of June, hundreds of events whole the city, cultural manifestation of city's potential, admission is free.[31]

- OpenCity Festival - outdoor performances festival, international artists and performers, make art installations in public places in Lublin.[32]

- Museum Night - like in whole world, Lublin's museums, are opened for visitors.

- Jarmark Jagielloński - Jagiellonian Trades - every year, about 100k of tourists, arriving in Lublin, only to feel middle-age atmosphere.

- Lubelskie Dni Kultury Studenckiej - an annual students' holiday, usually celebrated for about three weeks between May and June, students holiday in Lublin, are the longest in whole Poland.

- Słowo daję - Festiwal Opowiadaczy - I give you my word. Storytellers Festival

- Rozstaje Europy - International Festival of Document Film

- Mikołajki Folkowe - International Folk Music Festival ("St. Nicholas Folk Day") - organized by the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin.

- Strefa Inne Brzmienia ("Different Sounds Area" International Music Festival, which connects Lublin and Lviv citizens together.

- Lublin. Miasto Poezji - Poetry Festival organised by Ośrodek "Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN" and Polish Literature Institute of Catholic University in Lublin.

- Noc z Czechowiczem - A Night with Czechowicz - walking the trace, from "Poem about the City of Lublin" written by Józef Czechowicz at first full moon at July, organized by Ośrodek "Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN"

- Najstarsze Pieśni Europy - The oldest songs of Europe - Festival of Muzyka Kresów Foundation.

- Future Shorts - World Short Film Label

- Międzynarodowe Spotkania Teatrów Tańca - International Lublin Dance Festival

- Międzynarodowy Festiwal Teatralny "Konfrontacje" - International Theatre Festival "Confrontations"

- Festiwal Kultury Alternatywnej "ZdaErzenia" - Festival of Alternative Culture in Lublin

- Sąsiedzi - Festiwal Teatrów Europy Środkowej - Neighbours - Central European Theatres Festival

- Festiwal "Prowokacje" - Young Polish Fashion Creators Festival

- Studencki Ogólnopolski Festiwal Teatralny Kontestacje - Polish Students' Theatre Festival

- Międzynarodowe Spotkania Folklorystyczne im. Ignacego Wachowiaka - International Folk Dance Festival

- Lubelska Scena Rockowa - Lublin Rock Scene

- Taniec Znaku - first in Poland Internet Theatre, project of Lublin Maat Theatre,[33]

- Scena Młodych - Youth Scene, music festival

- Zwierciadła - Mirrors - High School Theatres Revision

- Zaduszki Jazzowe - Jazz All Souls' Day - it takes place in Dominican Order Monastery

- "Invitro" Scena Prapremier - "Invitro" Pre-première Scene[34]

- Solo życia - Classical Music Festival - creator of this festival is composer Mieczysław Jurecki

- Letnia Strefa Muzyki - Summer Music Area - Young polish musicians, promotion, on the small scene, organizers: Akwarela Cafe and Lublins' President Council

European Capital of Culture

In 2007, Lublin joined the group of Polish cities as candidates for the title of European Capital of Culture. Lublin won through to shortlisting, and was considered a black horse of that competition, but ultimately Wrocław was chosen.

Lublin is the city that symbolises European idea of integration, universal heritage of democracy and tolerance and the idea of dialogue between the cultures of the West and East. Lublin is a unique place where the cultures and religions meet. Here the East meets West, and the European Union meets Belarus and Ukraine. It is the perfect place of cooperation for European artists living within and outside the European Union. Lublin is a city open to artists, a place where unique initiatives and activities take place. Lublin means the experience of hundreds of years of rich history and cultural heritage which constitutes endless source of inspiration for new generations.European Culture is not only modern museums and enormous festivals, but first of all people and their activities, aims, aspirations, possibilities, potential and the desire for development. The development of culture and being granted the title of European Capital of Culture is a chance for development of one the poorest regions of the European Union."[35] — Adam Wasilewski, President of Lublin

Since 2007, there are special meetings, enter2016, which anyone could take part in. The city's Marketing Office have created a web page: Lublin2016.eu, available in Polish, English, Ukrainian, Spanish and Portuguese. Lublin is a pilot city of the Council of Europe and the European Commission Intercultural cities programme.

Education

There are five public schools of higher education:

- Maria Curie-Sklodowska University (UMCS)

- John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (KUL)

- Medical University of Lublin

- University of Life Sciences in Lublin

- Politechnika Lubelska

Lublin is home to a number of private higher education establishments.

- University of Economics and Innovation in Lublin

- Lubelska Szkoła Biznesu

- Wyższa Szkoła Nauk Społecznych z siedzibą w Lublinie

- Wyższa Szkoła Przedsiębiorczości i Administracji

- Vincent Pol University in Lublin

Sports

- Start Lublin - men's basketball team, 12th in Era Basket Liga in 2003–04 season.

- MKS Lublin - women's handball team playing in Polish Ekstraklasa Women's Handball League: 2nd place in 2003–04 season: also a winner of Women's EHF Cup in season 2000-01.

- Motor Lublin - professional football team competing in the Polish 3rd league (as of 2016).

- Lublinianka - men's football team competing in the Polish 4th league (as of 2016).

- Budowlani Lublin - a local Rugby Union team competing in the Polish, and surrounding district league.

- KMŻ Lublin speedway club competing in the Polish league (first division).

- LSKT - Lublin's Taekwon-do sport club.

- Tytani Lublin - semi-professional American football team

Politics

Members of Parliament elected from District 6 which consists of the City of Lublin.[36]

- Joanna Mucha (43 459),

- Włodzimierz Karpiński (10 260),

- Wojciech Wilk (6 348).

- Jakub Kulesza (15 058).

- Elżbieta Kruk (43 432),

- Gabriela Masłowska (23 287),

- Sylwester Tułajew (17 289),

- Artur Soboń (16 643),

- Jarosław Stawiarski (15 807),

- Krzysztof Michałkiewicz (15 806),

- Lech Sprawka (15 713),

- Krzysztof Głuchowski (9 924),

- Krzysztof Szulowski (9 019),

- Jerzy Bielecki (8 510).

Notable Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Lublin constituency:

- Zyta Gilowska, PiS

- Stanisław Głębocki, Samoobrona

- Arkadiusz Kasznia, SLD-UP

- Elżbieta Kruk, PiS

- Grzegorz Kurczuk, SLD-UP

- Robert Luśnia, LPR

- Andrzej Mańka, PiS

- Gabriela Masłowska, LPR

- Krzysztof Michałkiewicz, PiS

- Wiktor Osik, SLD-UP

- Zdzisław Podkański, PSL

- Tadeusz Polański, PSL

- Izabella Sierakowska, SLD-UP

- Zygmunt Jerzy Szymański, SLD-UP

- Leszek Świętochowski, PSL

- Marian Widz, Samoobrona

- Józef Żywiec, Samoobrona

Members of the European Parliament elected from the Lublin constituency include Lena Kolarska-Bobińska.

International relations

Lublin is a pilot city of the Council of Europe and the EU Intercultural cities programme.[37]

Twin towns — sister cities

Gallery

Another characteristic building in Lublin is the Royal Castle

Another characteristic building in Lublin is the Royal Castle.jpg) Juliusz Osterwa Theatre

Juliusz Osterwa Theatre Lublin Cathedral

Lublin Cathedral Interior of the Cathedral

Interior of the Cathedral Courtyard of the Dominican Abbey

Courtyard of the Dominican Abbey UMCS Botanical Gardens

UMCS Botanical Gardens- 14th-century Holy Trinity Chapel

- Frescoes inside the chapel

- Grodzka Gate

- A folk music concert during the Jagiellonian Fair

Lublin Graffiti Festival

Lublin Graffiti Festival Kozienalia, Lublin Days of Student Culture, beginning with a street parade

Kozienalia, Lublin Days of Student Culture, beginning with a street parade 440th anniversary of the Union of Lublin

440th anniversary of the Union of Lublin

Zemborzyce Lake

Zemborzyce Lake DZT Honker produced in Lublin by the DZT Tymińscy factory

DZT Honker produced in Lublin by the DZT Tymińscy factory The first part of a bypass road around Lublin

The first part of a bypass road around Lublin Radio & TV tower in Lublin

Radio & TV tower in Lublin A trolleybus in the centre of the city

A trolleybus in the centre of the city

Notable residents

- Biernat z Lublina, (~1465-~1529) Polish poet, fabulist, translator and physician

- Jacek Bąk, Polish footballer and captain of Poland during World Cup 2006

- Katarzyna Dolinska, contestant on Cycle 10 of America's Next Top Model, came in 5th place

- Rabbi Jacob ben Ephraim (unknown-1648), "The Gaon Rabbi Jacob of Lublin"

- Rabbi Joshua Falk (1555–1614), also known as Joshua ben Alexander HaCohen Falk

- Rabbi Shneur Zalman Fradkin (1830-1902), "The Toras Chessed"

- Rabbi Aryeh Tzvi Frumer (1884-1943), "The Kozhiglover Rav", Holocaust victim

- Rafał Gan-Ganowicz (1932-2002), mercenary, journalist, and activist

- Jacob Glatstein (1896–1971), literary critic

- Alter Mojze Goldman (1909–1988), resistance fighter

- Rabbi Zadok HaKohen Rabinowitz (1823-1900)

- Kitty Hart-Moxon (1926-), Holocaust survivor

- Rabbi Moses Isserles (1520-1572), "Rema"

- Jozef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812-1887), Polish writer, publisher, historian, journalist, scholar, political activist, painter and author

- Felix Lembersky (1913-1970), artist, painter

- Janusz Lewandowski (1951-), MEP, former minister of privatisation

- Rabbi Solomon Luria (1510-1573), "The Maharshal"

- Wincenty Pol (1807-1872), poet and geographer

- Rabbi Jacob Pollak (1460-1541)

- Stanisław Kostka Potocki (1755–1821), Polish nobleman, politician and writer

- Rabbi Sholom Rokeach (1781-1855), "Sar Sholom", the first Belzer Rebbe

- Yitzhak Sadeh (born Isaac Landsberg; 1890-1952), a founder of the Israel Defense Forces

- Rabbi Shalom Shachna (unknown-1558)

- Rabbi Meir Shapiro (1887-1933), "The Lubliner Rav"

- Rabbi Joel Sirkis (1561-1640), also known as Joel ben Samuel Sirkis

- Henryk Wieniawski (1835–1880), violinist; born in Lublin

- Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak of Lublin (1745–1815), "The Seer of Lublin"

- Rabbi Mordecai Yoffe (1530-1612), "The Levush"

- Wladyslaw Zmuda, Polish footballer and four-time World Cup participant

- Johann Hermann Zukertort, chess grand master

- Henio Zytomirski (1933-1942), Holocaust victim

See also

- Lublin Department (Polish: Departament Lubelski): a unit of administrative division and local government in Poland's Duchy of Warsaw, 1806–15

- Lublin Holocaust Memorial

- Old Jewish Cemetery, Lublin

- Tourism in Poland

- Union of Lublin (painting)

References

- ↑ "Interpelacja w sprawie mozliwosci i stanu realizacji postulatow" (pdf) (in Polish). Przewodniczago Rady Miasta Lublin. August 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Local history - Information about the town - Lublin - Virtual Shtetl". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ RP, Kancelaria Sejmu. "Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych".

- ↑ Lublin, UM. "Why Lublin? / Lublin – investment destination / Investors / Business / Lublin City Office". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Lublin, UM. "Standard of living in Lublin / Lublin – investment destination / Investors / Business / Lublin City Office". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Andrzej Rozwałka, Rafał Niedźwiadek, Marek Stasiak (2006). 'Origines Polonorum': Lublin wczesnośredniowieczny. The medieval urban complex of Lublin. A study of its spatial development. TRIO / FNP. pp. 199–203. Summary translated by Philip Earl Steele (PDF).

- ↑ "Tourist Guide: Lublin" (PDF). Lublin City Council. 2009. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Joshua D. Zimmerman, Poles, Jews and the Politics of Nationality, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2004, ISBN 0-299-19464-7, Google Print, p.16

- ↑ Diemut Majer; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2003). "Non-Germans" under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. JHU Press. p. 759. ISBN 978-0-8018-6493-3. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Helena Ziemba neé Herszenborn; Irena Gewerc-Gottlieb (2001). "Ścieżki Pamięci, Żydowskie Miasto w Lublinie – Losy, Miejsca, Historia (Path of Memory. Jewish Town in Lublin - Fate, Places, History)". 1. Mój Lublin Szczęśliwy i Nieszczęśliwy; 2. W Getcie i Kryjówce w Lublinie (PDF file, direct download 4.9 MB) (in Polish). Rishon LeZion, Israel; Lublin, Poland: Ośrodek "Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN" & Towarzystwo Przyjaźni Polsko-Izraelskiej w Lublinie. pp. 24, 27, 29, 30.

- ↑ "Climatological Normals for Lublin, Poland". Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Samorząd Miasta Lublin". Um.lublin.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ internet ART; www.internetart.pl (2007-05-31). "PAIiIZ | News | Inwestycje w Polsce". Paiz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Marcin Bielesz (2007-09-27). "Lublin fetuje specjalną strefę ekonomiczną". Miasta.gazeta.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ http://miasta.gazeta.pl/lublin/1,35640,4527639.html, http://ww2.tvp.pl/3903,20051107265122.strona

- ↑ opracowali: tn, dil, msa, ms, jb, pr, wa (2007-01-01). "Taki był 2006 rok". Miasta.gazeta.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Przegląd obiektów z emisjami". Emi.emitel.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Lublin - Rozkład jazdy pociągów PKP, autobusów PKS oraz komunikacji miejskiej dla miasta Lublin". Rozklad.mortin.pl. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ↑ "Zarząd Transportu Miejskiego w Lublinie".

- ↑ "Statystyki". Frekwencja zwiedzających. Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku. 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "The Reader". 30 January 2009 – via IMDb.

- ↑ "Lublin, Lwów | miasto filmowe - Aktualności". Film.lublin.eu. 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ↑ "Lublin-Lubelski Serwis Informacyjny-lublin". Lsi.lublin.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ http://www.teatr-osterwy.lublin.pl

- ↑ http://www.galeria.pl/nominacja.htm

- ↑ Fortuna(grafika), Kamil Resztak(php) & Grzegorz. "Filharmonia im. H. Wieniawskiego w Lublinie, filharmonia lubelska, filharmonia w Lublinie, orkiestra symfoniczna, koncerty, muzyka kameralna, zespoły :: Strona główna".

- ↑ http://zamek-lublin.pl/index.php?l=pl&r=1

- ↑ "Lubelski Serwis Informacyjny". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Polska, Wirtualna. "Wirtualna Polska - Wszystko co ważne - www.wp.pl".

- ↑ "Lublin - Foto Galeria - Strona główna - Fotografie Lublina".

- ↑ http://www.nockultury.pl

- ↑ "Festiwal Otwarte Miasto".

- ↑ "Theatre Maat". Di.com.pl. 2008-02-29. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ "TVP o Scenie InVitro". Ww6.tvp.pl. 2010-09-29. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ "Why Lublin?". Kultura.lublin.eu. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ Skomra, Sławomir. "Nowi posłowie z Lubelszczyzny. To ich wysłaliśmy do Sejmu (ZDJĘCIA)". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Council of Europe (2011). "Intercultural city: Lublin, Poland". coe.int. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 "Miasta Partnerskie Lublina" [Lublin - Partnership Cities] (in Polish). lublin.eu. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- ↑ Побратимские связи г. Бреста (in Russian). City.brest.by. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ Офіційний сайт міста Івано-Франківська. mvk.if.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ↑ "Portrait of Münster: Die Partnerstädte". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- ↑ "The Municipality of Lublin City". Um.lublin.eu. 1992-10-01. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Lublin's Partner and Friend Cities". The Municipality of Lublin City. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lublin. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lublin. |

- Lublin official website (in Polish) (in English)

- Official site Lublin the City of Inspiration (English version)

- Lublin Municipality official website (in Polish) (in English)