Lithuania

| Republic of Lithuania | |

|---|---|

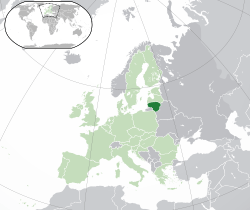

Location of Lithuania (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city |

Vilnius 54°41′N 25°19′E / 54.683°N 25.317°E |

| Official languages | Lithuanian |

| Ethnic groups (2015[1]) |

|

| Demonym | Lithuanian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic[2][3][4][5] |

| Dalia Grybauskaitė | |

| Saulius Skvernelis | |

| Viktoras Pranckietis | |

| Legislature | Seimas |

| Independence from Russia / Germany (1918) | |

| 9 March 1009 | |

• Coronation of Mindaugas | 6 July 1253 |

| 2 February 1386 | |

• Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth created | 1 July 1569 |

| 24 October 1795 | |

| 16 February 1918 | |

| 15 June 1940 | |

| 22 June 1941 | |

| July 1944 | |

| 11 March 1990 | |

• Independence recognized by the Soviet Union | 6 September 1991 |

| 17 September 1991 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

• Total | 65,300 km2 (25,200 sq mi) (123rd) |

• Water (%) | 1.35 |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 2,821,674 [6] (137th) |

• Density | 43/km2 (111.4/sq mi) (173rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $90.387 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $31,849[7] (41st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $42.826 billion |

• Per capita | $15,090[8] (49th) |

| Gini (2015) |

medium |

| HDI (2015) |

very high · 37th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| EEST (UTC+3) | |

| Date format | yyyy-mm-dd (CE) |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +370 |

| ISO 3166 code | LT |

| Internet TLD | .lta |

| |

Coordinates: 55°N 24°E / 55°N 24°E

Lithuania (/ˌlɪθuːˈeɪniə/,[11][12][13] Lithuanian: Lietuva [lʲɪɛtʊˈvɐ]), officially the Republic of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos Respublika), is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe.[14] One of the three Baltic states, it is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, to the east of Sweden and Denmark. It is bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, Poland to the south, and Kaliningrad Oblast (a Russian exclave) to the southwest. Lithuania has an estimated population of 2.8 million people as of 2017, and its capital and largest city is Vilnius. Lithuanians are a Baltic people. The official language, Lithuanian, along with Latvian, is one of only two living languages in the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family.

For centuries, the southeastern shores of the Baltic Sea were inhabited by various Baltic tribes. In the 1230s, the Lithuanian lands were united by Mindaugas, the King of Lithuania, and the first unified Lithuanian state, the Kingdom of Lithuania, was created on 6 July 1253. During the 14th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the largest country in Europe; present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Poland and Russia were the territories of the Grand Duchy. With the Lublin Union of 1569, Lithuania and Poland formed a voluntary two-state union, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth lasted more than two centuries, until neighboring countries systematically dismantled it from 1772–95, with the Russian Empire annexing most of Lithuania's territory.

As World War I neared its end, Lithuania's Act of Independence was signed on 16 February 1918, declaring the founding of the modern Republic of Lithuania. In the midst of the Second World War, Lithuania was first occupied by the Soviet Union and then by Nazi Germany. As World War II neared its end and the Germans retreated, the Soviet Union reoccupied Lithuania. On 11 March 1990, a year before the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union, Lithuania became the first Soviet republic to declare itself independent, resulting in the restoration of an independent State of Lithuania.

Lithuania is a member of the European Union, the Council of Europe, a full member of the Eurozone, Schengen Agreement and NATO. It is also a member of the Nordic Investment Bank, and part of Nordic-Baltic cooperation of Northern European countries. The United Nations Human Development Index lists Lithuania as a "very high human development" country. Lithuania has been among the fastest growing economies in the European Union and is ranked 21st in the world in the Ease of Doing Business Index.

History

Prehistoric

The first people settled in the territory of Lithuania after the last glacial period in the 10th millennium BC. Over a millennium, the Indo-Europeans, who arrived in the 3rd – 2nd millennium BC, mixed with the local population and formed various Baltic tribes. The first written mention of Lithuania is found in a medieval German manuscript, the Annals of Quedlinburg, in an entry dated 9 March 1009.[15]

Medieval

Initially inhabited by fragmented Baltic tribes, in the 1230s the Lithuanian lands were united by Mindaugas, who was crowned as King of Lithuania on 6 July 1253.[16] After his assassination in 1263, pagan Lithuania was a target of the Christian crusades of the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order. Despite the devastating century-long struggle with the Orders, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania expanded rapidly, overtaking former Slavic principalities of Kievan Rus'.

By the end of the 14th century, Lithuania was one of the largest countries in Europe and included present-day Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Poland and Russia.[17] The geopolitical situation between the west and the east determined the multicultural and multi-confessional character of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The ruling elite practised religious tolerance and Chancery Slavonic language was used as an auxiliary language to the Latin for official documents.

In 1385, the Grand Duke Jogaila accepted Poland's offer to become its king. Jogaila embarked on gradual Christianization of Lithuania and established a personal union between Poland and Lithuania. It implied that Lithuania, the fiercely independent land, was one of the last pagan areas of Europe to adopt Christianity.

After two civil wars, Vytautas the Great became the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1392. During his reign, Lithuania reached the peak of its territorial expansion, centralization of the state began, and the Lithuanian nobility became increasingly prominent in state politics. In the great Battle of the Vorskla River in 1399, the combined forces of Tokhtamysh and Vytautas were defeated by the Mongols. Thanks to close cooperation, the armies of Lithuania and Poland achieved a great victory over the Teutonic Knights in 1410 at the Battle of Grunwald, one of the largest battles of medieval Europe.[18][19][20]

After the deaths of Jogaila and Vytautas, the Lithuanian nobility attempted to break the union between Poland and Lithuania, independently selecting Grand Dukes from the Jagiellon dynasty. But, at the end of the 15th century, Lithuania was forced to seek a closer alliance with Poland when the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow threatened Lithuania's Russian principalities and sparked the Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars and the Livonian War.

Modern

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was created in 1569. As a member of the Commonwealth, Lithuania retained its institutions, including a separate army, currency, and statutory laws.[21] Eventually Polonization affected all aspects of Lithuanian life: politics, language, culture, and national identity. From the mid-16th to the mid-17th centuries, culture, arts, and education flourished, fueled by the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. From 1573, the Kings of Poland and Grand Dukes of Lithuania were elected by the nobility, who were granted ever increasing Golden Liberties. These liberties, especially the liberum veto, led to anarchy and the eventual dissolution of the state.

During the Northern Wars (1655–1661), the Lithuanian territory and economy were devastated by the Swedish army. Before it could fully recover, Lithuania was ravaged during the Great Northern War (1700–1721). The war, a plague, and a famine caused the deaths of approximately 40% of the country's population.[22] Foreign powers, especially Russia, became dominant in the domestic politics of the Commonwealth. Numerous factions among the nobility used the Golden Liberties to prevent any reforms. Eventually, the Commonwealth was partitioned in 1772, 1792, and 1795 by the Russian Empire, Prussia, and Habsburg Austria.

The largest area of Lithuanian territory became part of the Russian Empire. After unsuccessful uprisings in 1831 and 1863, the Tsarist authorities implemented a number of Russification policies. They banned the Lithuanian press, closed cultural and educational institutions, and made Lithuania part of a new administrative region called Northwestern Krai. The Russification failed owing to an extensive network of book smugglers and secret Lithuanian home schooling.

After the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), when German diplomats assigned what were seen as Russian spoils of war to Turkey, the relationship between Russia and the German Empire became complicated. The Russian Empire resumed the construction of fortresses at its western borders for defence against a potential invasion from Germany in the West. On 7 July 1879 the Russian Emperor Alexander II approved of a proposal from the Russian military leadership to build the largest "first-class" defensive structure in the entire state – the 65 km2 (25 sq mi) Kaunas Fortress.[23] Large numbers of Lithuanians went to the United States in 1867–1868 after a famine.[24] A Lithuanian National Revival laid the foundations of the modern Lithuanian nation and independent Lithuania.

20th and 21st centuries

During World War I, the Council of Lithuania (Lietuvos Taryba) declared the independence of Lithuania and the re-establishment of the Lithuanian State on 16 February 1918. Lithuania's foreign policy was dominated by territorial disputes with Poland and Germany. The Vilnius Region and Vilnius, the historical capital of Lithuania (and so designated in the Constitution of Lithuania), were seized by the Polish army during Żeligowski's Mutiny in October 1920 and incorporated two years later into Poland. For 19 years, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania. The Polish control over Vilnius was greatly resented by Lithuania; there were no diplomatic relations between the two states for most of the period between the two World Wars.

Acquired during the Klaipėda Revolt of 1923, the Klaipėda Region (German: Memelland) was ceded to Nazi Germany after a German ultimatum of March 1939. During the interwar period, the domestic affairs of Lithuania were controlled by the authoritarian President Antanas Smetona and his party, the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, which came to power after the Lithuanian coup d'état of 1926.

1939–1941

The Soviet Union returned Vilnius to Lithuania after the Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland in September 1939.[25] In June 1940, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Lithuania in accordance to the secret protocols of Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[26][27] The occupation was followed by mass arrests and deportations with Lithuania having 34,000 citizens removed. According to a Lithuanian government official, this was the start of a planned removal of 700,000 from Lithuania.[28]:48

1941–1944

A year later, the Soviet Union was attacked by Nazi Germany, leading to the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. The Germans and their collaborators[28]:54–56 immediately began to round up and murder civilians, including intellectuals, army officers, Romani people and Jews.[29] By 1 December 1941, over 120,000 Lithuanian Jews, or 91–95% of Lithuania's pre-war Jewish community, had been killed.[28]:110

10 of the 25 Lithuanian police battalions, working with the Nazi Einsatzkommando, were involved in the mass killings and are thought to have executed 78,000 people.[28]:148

Lithuanian partisans did exist, but few supported the communists. Lithuanian army soldiers, who had been assigned to the 29th Rifle Corps of the Red Army, deserted or surrendered to the Germans in June 1941, resulting in the unit being disbanded in August 1941.

1944–1991

After the retreat of the German armed forces, the Soviets reestablished the annexation of Lithuania in 1944. Under border changes promulgated at the Potsdam Conference of 1945, the former German Memelland, with its Baltic port Memel (Lithuanian: Klaipėda), was again transferred to Lithuania, which was now referred to as the Lithuanian SSR. Most of Memelland's German residents had fled the area in the final months of World War II.

As part of their program of nationalisation, collectivization and general sovietization of everyday life, the Soviets deported large numbers of Lithuanians to Siberia.[30] From 1944 to 1952, approximately 100,000 Lithuanian partisans fought a guerrilla war against the Soviet system. An estimated 30,000 partisans and their supporters were killed; many more were arrested and deported to Siberian gulags. It is estimated that during World War II and the subsequent Soviet annexation, Lithuania lost 780,000 people.[31]

The advent of perestroika and glasnost in the late 1980s allowed the establishment of Sąjūdis, an anti-Communist independence movement. After a landslide victory in elections to the Supreme Soviet, members of Sąjūdis proclaimed Lithuania's independence on 11 March 1990, making Lithuania the first Soviet republic to do so. The Soviet Union attempted to suppress the secession by imposing an economic blockade. On the night of 13 January 1991, Soviet troops attacked the Vilnius TV Tower, killing 14 Lithuanian civilians and wounding 600 others.[32][33] On 31 July 1991, Soviet paramilitaries killed seven Lithuanian border guards on the Belarusian border in what became known as the Medininkai Massacre.

On 4 February 1991, Iceland became the first country to recognise Lithuania's independence. After the Soviet August Coup, independent Lithuania received wide official recognition, and joined the United Nations on 17 September 1991.

1991–present

The last Russian troops left Lithuania on 31 August 1993,[34] even earlier than they departed from East Germany. Lithuania, seeking closer ties with the West, applied for NATO membership in 1994. After a transition from a planned economy to a free market, Lithuania became a full member of NATO and the European Union in the spring of 2004 and a member of the Schengen Agreement on 21 December 2007.

Geography

Lithuania is located in Northern Europe and covers an area of 65,200 km2 (25,200 sq mi).[35] It lies between latitudes 53° and 57° N, and mostly between longitudes 21° and 27° E (part of the Curonian Spit lies west of 21°). It has around 99 kilometres (61.5 mi) of sandy coastline, only about 38 kilometres (24 mi) of which face the open Baltic Sea, less than the other two Baltic Sea countries. The rest of the coast is sheltered by the Curonian sand peninsula. Lithuania's major warm-water port, Klaipėda, lies at the narrow mouth of the Curonian Lagoon (Lithuanian: Kuršių marios), a shallow lagoon extending south to Kaliningrad. The country's main and largest river, the Nemunas River, and some of its tributaries carry international shipping.

Lithuania lies at the edge of the North European Plain. Its landscape was smoothed by the glaciers of the last ice age, and is a combination of moderate lowlands and highlands. Its highest point is Aukštojas Hill at 294 metres (965 ft) in the eastern part of the country. The terrain features numerous lakes (Lake Vištytis, for example) and wetlands, and a mixed forest zone covers over 33% of the country.

After a re-estimation of the boundaries of the continent of Europe in 1989, Jean-George Affholder, a scientist at the Institut Géographique National (French National Geographic Institute), determined that the geographic centre of Europe was in Lithuania, at 54°54′N 25°19′E / 54.900°N 25.317°E, 26 kilometres (16 mi) north of Lithuania's capital city of Vilnius.[36] Affholder accomplished this by calculating the centre of gravity of the geometrical figure of Europe.

Climate

Lithuania's climate, which ranges between maritime and continental, is relatively mild. Average temperatures on the coast are −2.5 °C (27.5 °F) in January and 16 °C (61 °F) in July. In Vilnius the average temperatures are −6 °C (21 °F) in January and 17 °C (63 °F) in July. During the summer, 20 °C (68 °F) is common during the day while 14 °C (57 °F) is common at night; in the past, temperatures have reached as high as 30 or 35 °C (86 or 95 °F). Some winters can be very cold. −20 °C (−4 °F) occurs almost every winter. Winter extremes are −34 °C (−29 °F) in coastal areas and −43 °C (−45 °F) in the east of Lithuania.

The average annual precipitation is 800 mm (31.5 in) on the coast, 900 mm (35.4 in) in the Samogitia highlands and 600 mm (23.6 in) in the eastern part of the country. Snow occurs every year, it can snow from October to April. In some years sleet can fall in September or May. The growing season lasts 202 days in the western part of the country and 169 days in the eastern part. Severe storms are rare in the eastern part of Lithuania but common in the coastal areas.

The longest records of measured temperature in the Baltic area cover about 250 years. The data show warm periods during the latter half of the 18th century, and that the 19th century was a relatively cool period. An early 20th century warming culminated in the 1930s, followed by a smaller cooling that lasted until the 1960s. A warming trend has persisted since then.[37]

Lithuania experienced a drought in 2002, causing forest and peat bog fires.[38] The country suffered along with the rest of Northwestern Europe during a heat wave in the summer of 2006.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.0 (95) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.1 (98.8) |

35.1 (95.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.9 (25) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61) |

12.2 (54) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−2.8 (27) |

1.5 (34.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.2 (54) |

11.9 (53.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −40.5 (−40.9) |

−42.9 (−45.2) |

−37.5 (−35.5) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−2.8 (27) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−34.0 (−29.2) |

−42.9 (−45.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.2 (1.425) |

30.1 (1.185) |

33.9 (1.335) |

42.9 (1.689) |

52.0 (2.047) |

69.0 (2.717) |

76.9 (3.028) |

77.0 (3.031) |

60.3 (2.374) |

49.9 (1.965) |

50.4 (1.984) |

47.0 (1.85) |

625.5 (24.626) |

| Source #1: Records of Lithuanian climate[39][40] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weatherbase[41] | |||||||||||||

Politics

|

|

| Dalia Grybauskaitė President |

Saulius Skvernelis Prime Minister |

Since Lithuania declared the restoration of its independence on 11 March 1990, it has maintained strong democratic traditions. It held its first independent general elections on 25 October 1992, in which 56.75% of voters supported the new constitution.[42] There were intense debates concerning the constitution, particularly the role of the president. A separate referendum was held on 23 May 1992 to gauge public opinion on the matter, and 41% of voters supported the restoration of the President of Lithuania.[42] Through compromise, a semi-presidential system was agreed on.[2]

The Lithuanian head of state is the president, directly elected for a five-year term and serving a maximum of two terms. The president oversees foreign affairs and national security, and is the commander-in-chief of the military. The president also appoints the prime minister and, on the latter's nomination, the rest of the cabinet, as well as a number of other top civil servants and the judges for all courts.

The current Lithuanian head of state, Dalia Grybauskaitė was elected on 17 May 2009, becoming the first female president in the country's history, and the second female head of state in the Baltic States after Latvia elected their first female political leader in 1999.[43] Dalia Grybauskaitė was re-elected for a second term in 2014.

The judges of the Constitutional Court (Konstitucinis Teismas) serve nine-year terms. They are appointed by the President, the Chairman of the Seimas, and the Chairman of the Supreme Court, each of whom appoint three judges. The unicameral Lithuanian parliament, the Seimas, has 141 members who are elected to four-year terms. 71 of the members of its members are elected in single member constituencies, and the others in a nationwide vote by proportional representation. A party must receive at least 5% of the national vote to be eligible for any of the 70 national seats in the Seimas.

Administrative divisions

The current system of administrative division was established in 1994 and modified in 2000 to meet the requirements of the European Union. The country's 10 counties (Lithuanian: singular – apskritis, plural – apskritys) are subdivided into 60 municipalities (Lithuanian: singular – savivaldybė, plural – savivaldybės), and further divided into 500 elderships (Lithuanian: singular – seniūnija, plural – seniūnijos).

Municipalities have been the most important unit of administration in Lithuania since the system of county governorship (apskrities viršininkas) was dissolved in 2010.[44] Some municipalities are historically called "district municipalities" (often shortened to "district"), while others are called "city municipalities" (sometimes shortened to "city"). Each has its own elected government. The election of municipality councils originally occurred every three years, but now takes place every four years. The council appoints elders to govern the elderships. Mayors have been directly elected since 2015; prior to that, they were appointed by the council.[45]

Elderships, numbering over 500, are the smallest administrative units and do not play a role in national politics. They provide necessary local public services—for example, registering births and deaths in rural areas. They are most active in the social sector, identifying needy individuals or families and organizing and distributing welfare and other forms of relief.[46] Some citizens feel that elderships have no real power and receive too little attention, and that they could otherwise become a source of local initiative for addressing rural problems.[47]

| County | Area (km²) | Population(thousands) in 2015[48] | Nominal GDP billions EUR in 2015[48] | Nominal GDP billions USD in 2015[48] | Nominal GDP per capita EUR in 2015[48] | Nominal GDP per capita USD in 2015[48] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alytus County | 5,425 | 149 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 8,300 | 9,100 |

| Kaunas County | 8,089 | 585 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 12,700 | 14,000 |

| Klaipėda County | 5,209 | 328 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 13,200 | 14,500 |

| Marijampolė County | 4,463 | 153 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 7,900 | 8,700 |

| Panevėžys County | 7,881 | 237 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 9,700 | 10,700 |

| Šiauliai County | 8,540 | 284 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 9,600 | 10,600 |

| Tauragė County | 4,411 | 104 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 7,200 | 8,000 |

| Telšiai County | 4,350 | 145 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 9,300 | 10,200 |

| Utena County | 7,201 | 141 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 8,300 | 9,100 |

| Vilnius County | 9,729 | 807 | 15.1 | 16.6 | 18,700 | 20,600 |

| Lithuania | 65,300 | 2907 | 37.2 | 41.0 | 12,900 | 14,200 |

Foreign relations

Lithuania became a member of the United Nations on 18 September 1991, and is a signatory to a number of its organizations and other international agreements. It is also a member of the European Union, the Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, as well as NATO and its adjunct North Atlantic Coordinating Council. Lithuania gained membership in the World Trade Organization on 31 May 2001, and currently seeks membership in the OECD and other Western organizations.

Lithuania has established diplomatic relations with 149 countries.[49]

In 2011, Lithuania hosted the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Ministerial Council Meeting. During the second half of 2013, Lithuania assumed the role of the presidency of the European Union.

Lithuania is also active in developing cooperation among northern European countries. It has been a member of the Baltic Council since its establishment in 1993. The Baltic Council, located in Tallinn, is a permanent organisation of international cooperation that operates through the Baltic Assembly and the Baltic Council of Ministers.

Lithuania also cooperates with Nordic and the two other Baltic countries through the NB8 format. A similar format, NB6, unites Nordic and Baltic members of EU. NB6's focus is to discuss and agree on positions before presenting them to the Council of the European Union and at the meetings of EU foreign affairs ministers.

The Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS) was established in Copenhagen in 1992 as an informal regional political forum. Its main aim is to promote integration and to close contacts between the region's countries. The members of CBSS are Iceland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Russia, and the European Commission. Its observer states are Belarus, France, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine.

The Nordic Council of Ministers and Lithuania engage in political cooperation to attain mutual goals and to determine new trends and possibilities for joint cooperation. The Council's information office aims to disseminate Nordic concepts and to demonstrate and promote Nordic cooperation.

Lithuania, together with the five Nordic countries and the two other Baltic countries, is a member of the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB) and cooperates in its NORDPLUS programme, which is committed to education.

The Baltic Development Forum (BDF) is an independent nonprofit organization that unites large companies, cities, business associations and institutions in the Baltic Sea region. In 2010 the BDF's 12th summit was held in Vilnius.[50]

In 2013, Lithuania was elected to the United Nations Security Council for a two-year term,[51] becoming the first Baltic country elected to this post.

Military

The Lithuanian Armed Forces is the name for the unified armed forces of Lithuanian Land Force, Lithuanian Air Force, Lithuanian Naval Force, Lithuanian Special Operations Force and other units: Logistics Command, Training and Doctrine Command, Headquarters Battalion, Military Police. Directly subordinated to the Chief of Defence are the Special Operations Forces and Military Police. The Reserve Forces are under command of the Lithuanian National Defence Volunteer Forces.

The Lithuanian Armed Forces consist of some 15,000 active personnel, which may be supported by reserve forces.[52] Compulsory conscription ended in 2008 but was reintroduced in 2015.[53] The Lithuanian Armed Forces currently have deployed personnel on international missions in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Mali and Somalia.[54]

In March 2004, Lithuania became a full member of the NATO. Since then, fighter jets of NATO members are deployed in Zokniai airport and provide safety for the Baltic airspace.

Since the summer of 2005 Lithuania has been part of the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan (ISAF), leading a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) in the town of Chaghcharan in the province of Ghor. The PRT includes personnel from Denmark, Iceland and USA. There are also special operation forces units in Afghanistan, placed in Kandahar Province. Since joining international operations in 1994, Lithuania has lost two soldiers: 1st Lt. Normundas Valteris fell in Bosnia, as his patrol vehicle drove over a mine. Sgt. Arūnas Jarmalavičius was fatally wounded during an attack on the camp of his Provincial Reconstruction Team in Afghanistan.[55]

The Lithuanian National Defence Policy aims to guarantee the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of the state, the integrity of its land, territorial waters and airspace, and its constitutional order. Its main strategic goals are to defend the country's interests, and to maintain and expand the capabilities of its armed forces so they may contribute to and participate in the missions of NATO and European Union member states.[56]

The defense ministry is responsible for combat forces, search and rescue, and intelligence operations. The 5,000 border guards fall under the Interior Ministry's supervision and are responsible for border protection, passport and customs duties, and share responsibility with the navy for smuggling and drug trafficking interdiction. A special security department handles VIP protection and communications security.

Economy

.jpg)

Lithuanian GDP experienced very high real growth rates in the decade before 2009, peaking at 11.1% in 2007. As a result, the country was often termed as a Baltic Tiger. However, 2009 marked a dramatic decline in GDP at −14.9% attributed to overheating of the economy. The economy resumed growth in the following years at a lower but more sustainable pace, driven by domestic demand and exports rather than housing and financial bubbles.[60] The unemployment rate was 9.1% at the end of 2015, down from 17.8% in 2010.[61]

Lithuania has a flat tax rate rather than a progressive scheme. According to Eurostat,[62] the personal income tax (15%) and corporate tax (15%) rates in Lithuania are among the lowest in the EU. The country has the lowest implicit rate of tax on capital (9.8%) in the EU. Lithuania also has the lowest overall taxation as a percentage of GDP (27.2) in the European Union.[62]

Lithuanian income levels are somewhat lower than in older EU Member States but higher than in most new EU Member States that have joined in the last decade. According to Eurostat data, Lithuanian GDP per capita(PPP) stood at 75% of the EU average in 2015.[63] Average annual wage (before taxes, for full-time employees) in Lithuania stood at around $10,000, still around 1/5 of that in the richest EU member states in 2015. As of 2016, Lithuania had average wealth per adult, at $22,411.[64]

Structurally, there is a gradual but consistent shift towards a knowledge-based economy with special emphasis on biotechnology (industrial and diagnostic). The major biotechnology companies and laser manufacturers (Ekspla, Šviesos Konversija) of the Baltics are concentrated in Lithuania. Also mechatronics and information technology (IT) are seen as prospective knowledge-based economy directions.

In 2009, Barclays established Technology Centre Lithuania – one of four strategic engineering centres supporting the Barclays Retail Banking businesses across the globe.[65] In 2011, Western Union officially opened their new European Regional Operating Centre in Vilnius.[66] The stated position of the Lithuanian government is that the focus of Lithuanian economy is high added-value products and services.[67] Among other international companies operating in Lithuania are: PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, Societe Generale, UniCredit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Phillip Morris, Kraft Foods, Mars, Marks & Spencer, GlaxoSmithKline, United Colors of Benetton, Deichmann, Statoil, Neste Oil, Lukoil, Tele2, Hesburger and Modern Times Group. TeliaSonera, ICA and Carlsberg respectively own local telecommunications company Omnitel, retailer Rimi and beer breweries (Švyturys, Kalnapilis and Utenos Alus). Lithuanian banking sector is dominated by the Scandinavian banks: Swedbank, SEB, Nordea, Danske Bank, DNB ASA.

Among the biggest private owned Lithuanian companies are: ORLEN Lietuva, Maxima Group, Achema Group, Lukoil Baltija, Linas Agro Group, Indorama Polymers Europe, Palink, Sanitex.[68][69] Corporate tax rate in Lithuania is 15% and 5% for small businesses. The government offers special incentives for investments into the high-technology sectors and high value-added products. Most of the trade Lithuania conducts is within the European Union and Russia.

The litas was the national currency until 2015, when it was replaced by the euro at the rate of EUR 1.00 = LTL 3.45280.[70] Litas had been pegged to the euro at this rate since 2 February 2002.[71]

Infrastructure

Communication

According to the Speedtest.net website, as of 30 October 2011 Lithuania ranks first in the world by the internet upload speed and download speed, schools and corporations ignored.[72][73] The high speeds are largely due to Lithuania having the EU's and Europe's most available FTTH network. According to a yearly study published by the FTTH Council Europe in 2013,[74] the country has connected 100% of households to the FTTH network. 31% of these households are subscribers to this network at the time of publishing. Lithuania has thus Europe's most available fibre network and also has the highest FTTH penetration. Sweden has the next highest FTTH penetration with 23%.

Transport

.png)

The country boasts a well-developed modern infrastructure of railways, airports and four-lane highways. Lithuania has an extensive network of motorways. The best known motorways are A1, connecting Vilnius with Klaipėda via Kaunas, as well as A2, connecting Vilnius and Panevėžys. One of the most used is the European route E67 highway running from Warsaw to Tallinn, via Kaunas and Riga.

The Port of Klaipėda is the only commercial port in Lithuania. In a record year for the port, in 2011 45.5 million tons of cargo were handled (including Būtingė oil terminal figures), making it one of the biggest in the Baltic Sea.[75]

Vilnius International Airport is the largest airport. It served 3.8 million passengers in 2016.[76] Other international airports include Kaunas International Airport, Palanga International Airport and Šiauliai International Airport.

Lithuania received its first railway connection in the middle of the 19th century, when the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway was constructed. It included a stretch from Daugavpils via Vilnius and Kaunas to Virbalis. The first and only still operating in the Baltic states Kaunas Railway Tunnel was completed in 1860. Lithuanian Railways' main network consists of 1,762 km (1,095 mi) of 1,520 mm (4 ft 11.8 in) broad gauge railway of which 122 km (76 mi) are electrified. They also operate 115 km (71 mi) of standard gauge lines.[77] The Trans-European standard gauge Rail Baltica railway, linking Helsinki–Tallinn–Riga–Kaunas–Warsaw and continuing on to Berlin is under construction.

Energy

Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant was a Soviet-era nuclear station. Unit No. 1 was closed in December 2004, as a condition of Lithuania's entry into the European Union; the plant is similar to the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in its lack of a robust containment structure. The remaining unit, as of 2006, supplied about 70% of Lithuania's electrical demand.[78] Unit No. 2 was closed down on 31 December 2009. Proposals have been made to construct another – Visaginas Nuclear Power Plant in Lithuania.[79] However, a non-binding referendum held in October 2012 clouded the prospects for the Visaginas project, as 63% of voters said no to a new nuclear power plant.[80]

The country's main primary source of electrical power is Elektrėnai Power Plant. Other primary sources of Lithuania's electrical power are Kruonis Pumped Storage Plant and Kaunas Hydroelectric Power Plant. Kruonis Pumped Storage Plant is the only in the Baltic states power plant to be used for regulation of the power system's operation with generating capacity of 900 MW for at least 12 hours.[81] As of 2015, 66% of electrical power was imported.[82]

Demographics

Since the Neolithic period the native inhabitants of the Lithuanian territory have not been replaced by any other ethnic group, so there is a high probability that the inhabitants of present-day Lithuania have preserved the genetic composition of their forebears relatively undisturbed by the major demographic movements,[83] although without being actually isolated from them.[84] The Lithuanian population appears to be relatively homogeneous, without apparent genetic differences among ethnic subgroups.[85]

A 2004 analysis of MtDNA in the Lithuanian population revealed that Lithuanians are close to the Slavic and Finno-Ugric speaking populations of Northern and Eastern Europe. Y-chromosome SNP haplogroup analysis showed Lithuanians to be closest to Latvians and Estonians.[86]

According to 2014 estimates, the age structure of the population was as follows: 0–14 years, 13.5% (male 243,001/female 230,674); 15–64 years: 69.5% (male 1,200,196/female 1,235,300); 65 years and over: 16.8% (male 207,222/female 389,345).[87] The median age was 41.2 years (male: 38.5, female: 43.7).[88]

Lithuania has a sub-replacement fertility rate: the total fertility rate (TFR) in Lithuania is 1.59 children born/woman (2015 estimates).[89] As of 2014, 29% of births were to unmarried women.[90] The age at first marriage in 2013 was 27 years for women and 29.3 years for men.[91]

Ethnic groups

Ethnic Lithuanians make up about five-sixths of the country's population and Lithuania has the most homogenous population in the Baltic States. In 2015, the population of Lithuania stands at 2,921,262, 86.7% of whom are ethnic Lithuanians who speak Lithuanian, which is the official language of the country. Several sizable minorities exist, such as Poles (5.6%), Russians (4.8%), Belarusians (1.3%) and Ukrainians (0.7%).[1]

Poles are the largest minority, concentrated in southeast Lithuania (the Vilnius region). Russians are the second largest minority, concentrated mostly in two cities. They constitute sizeable minorities in Vilnius (12%)[92] and Klaipėda (19.6%),[93] and a majority in the town of Visaginas (52%).[94] About 3,000 Roma live in Lithuania, mostly in Vilnius, Kaunas and Panevėžys; their organizations are supported by the National Minority and Emigration Department.[95] For centuries a small Tatar community has flourished in Lithuania.[96]

The official language is Lithuanian. Other languages, such as Russian, Polish, Belarusian and Ukrainian, are spoken in the larger cities, in the Šalčininkai District Municipality and the Vilnius District Municipality. Yiddish is spoken by members of the tiny remaining Jewish community in Lithuania. According to the Lithuanian population census of 2011,[93] about 85% of the country's population speak Lithuanian as their native language, 7,2% are native speakers of Russian and 5,3% of Polish. According to the Eurobarometer survey conducted in 2012, 80% of Lithuanians can speak Russian and 38% can speak English. Most Lithuanian schools teach English as the first foreign language, but students may also study German, or, in some schools, French or Russian. Schools where Russian or Polish are the primary languages of education exist in the areas populated by these minorities.

Urbanization

There has been a steady movement of population to the cities since the 1990s, encouraged by the planning of regional centres, such as Alytus, Marijampolė, Utena, Plungė, and Mažeikiai. By the early 21st century, about two-thirds of the total population lived in urban areas. As of 2015, 66.5% of the total population lives in urban areas.[87] The largest city is Vilnius, followed by Kaunas, Klaipėda, Šiauliai, and Panevėžys.

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

Vilnius  Kaunas |

1 | Vilnius | Vilnius | 542,990 | 11 | Kėdainiai | Kaunas | 25,107 |  Klaipėda  Šiauliai |

| 2 | Kaunas | Kaunas | 299,466 | 12 | Telšiai | Telšiai | 24,855 | ||

| 3 | Klaipėda | Klaipėda | 155,032 | 13 | Tauragė | Tauragė | 24,681 | ||

| 4 | Šiauliai | Šiauliai | 103,676 | 14 | Ukmergė | Vilnius | 21,981 | ||

| 5 | Panevėžys | Panevėžys | 94,399 | 15 | Visaginas | Utena | 20,028 | ||

| 6 | Alytus | Alytus | 55,012 | 16 | Kretinga | Klaipėda | 19,999 | ||

| 7 | Mažeikiai | Telšiai | 38,120 | 17 | Radviliškis | Šiauliai | 18,882 | ||

| 8 | Marijampolė | Marijampolė | 37,914 | 18 | Plungė | Telšiai | 18,717 | ||

| 9 | Jonava | Kaunas | 28,719 | 19 | Vilkaviškis | Marijampolė | 16,707 | ||

| 10 | Utena | Utena | 27,120 | 20 | Šilutė | Klaipėda | 16,686 | ||

Functional urban areas

| Functional urban areas | Population(thousands) 2014 |

|---|---|

| Vilnius | 693 |

| Kaunas | 391 |

Health

As of 2015 Lithuanian life expectancy at birth was 73.4 (67.4 years for males and 78.8 for females)[99] and the infant mortality rate was 6.2 per 1,000 births. The annual population growth rate increased by 0.3% in 2007. At 33.5 people per 100,000 in 2012, Lithuania has seen a dramatic rise in suicides in the post-Soviet years, and now records the fourth highest age-standardized suicide rate in the world, according to WHO.[100] Lithuania also has the highest homicide rate in the EU.[101]

Religion

As per the 2011 census, 77.2% of Lithuanians belonged to the Roman Catholic Church.[102] The Church has been the majority denomination since the Christianisation of Lithuania at the end of the 14th century. The Reformation did not impact Lithuania to a great extent as seen in Estonia or Latvia as generally only local Germans in the Klaipėda/Memel area turned Protestant, while Lithuanians and Poles remained Catholic, and Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians—Eastern Orthodox. Some priests actively led the resistance against the Communist regime (symbolised by the Hill of Crosses).

4.1% are Eastern Orthodox, mainly among the Russian minority. This group is distinguishable into the Eastern Orthodox Church and Old Believers.

Protestants are 0.8%, of which 0.6% are Lutheran and 0.2% are Reformed. According to Losch (1932), the Lutherans were 3.3% of the total population;[103] they were mainly Germans in the Memel territory (now Klaipėda). There was also a tiny Reformed community (0,5%)[103] which still persists. Protestantism has declined with the removal of the German population, and today it is mainly represented by ethnic Lithuanians throughout the northern and western parts of the country, as well as in large urban areas. Believers and clergy suffered greatly during the Soviet occupation, with many killed, tortured or deported to Siberia. Newly arriving evangelical churches have established missions in Lithuania since 1990.[104]

6.1% have no religion.

Lithuania was historically home to a significant Jewish community and was an important center of Jewish scholarship and culture from the 18th century until the eve of World War II. Prior to the war, the Jewish population, outside of the Vilnius region (which was then in Poland), numbered about 160,000. In September 1939, tens of thousands of Polish Jews became Lithuanian subjects when the Soviets transferred the Vilnius region (of the former Polish state) to Lithuania and additional Jewish refugees arrived in Lithuania during the period prior to June 1941. Of the approximately 220,000 Jews who lived in the Republic of Lithuania in June 1941, almost all were entirely annihilated during the Holocaust.[105][106] The community numbered about 4,000 at the end of 2009.[107]

According to the most recent Eurobarometer Poll in 2010,[108] 47% of Lithuanian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", 37% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", and 12% said that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, god, or life force".

Education

The first documented school in Lithuania was established in 1387 at Vilnius Cathedral.[109] The school network was influenced by the Christianization of Lithuania. Several types of schools were present in medieval Lithuania – cathedral schools, where pupils were prepared for priesthood; parish schools, offering elementary education; and home schools dedicated to educating the children of the Lithuanian nobility. Before Vilnius University was established in 1579, Lithuanians seeking higher education attended universities in foreign cities, including Kraków, Prague, and Leipzig, among others.[109] During the Interbellum a national university – Vytautas Magnus University was founded in Kaunas.

The Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania proposes national educational policies and goals. These are sent to the Seimas for ratification. Laws govern long-term educational strategy along with general laws on standards for higher education, vocational training, law and science, adult education, and special education.[110] County administrators, municipal administrators, and school founders (including non-governmental organizations, religious organizations, and individuals) are responsible for implementing these policies.[110] By constitutional mandate, ten years of formal enrollment in an educational institution is mandatory, ending at age 16.[111]

14.7% of the 2014 state budget was allocated to education expenses.[112] Primary and secondary schools receive funding from the state via their municipal or county administrations. The Constitution of Lithuania guarantees tuition-free attendance at public institutions of higher education for students deemed 'good'; the number of such students has varied over the past decade, with 53.5% exempted from tuition fees in 2014.[113]

The World Bank designates the literacy rate of Lithuanian persons aged 15 years and older as 100% [114] and, according to Eurostat Lithuania leads among other countries of EU by people with secondary education (93.3%).[115] As of 2012, 34% of the population aged 25 to 64 had completed tertiary education; 59.1% had completed upper secondary and post-secondary (non-tertiary) education.[116] According to Invest in Lithuania, Lithuania has twice as many people with higher education than the EU-15 average and the proportion is the highest in the Baltic. Also, 90% of Lithuanians speak at least one foreign language and half of the population speaks two foreign languages, mostly Russian and English.[117]

As with other Baltic nations, in particular Latvia, the large volume of higher education graduates within the country, coupled with the high rate of spoken second languages is contributing to an education brain drain. Many Lithuanians are choosing to emigrate seeking higher earning employment and studies throughout Europe. Since their inclusion into the European Union in 2004, Lithuania's population has fallen by approximately 180,000 people.[118][119]

As of 2008, there were 15 public universities in Lithuania, 6 private institutions, 16 public colleges, and 11 private colleges.[120] Vilnius University is one of the oldest universities in Northern Europe and the largest university in Lithuania. Kaunas University of Technology is the largest technical university in the Baltic States and the 2nd largest university in Lithuania. Other universities include Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, Lithuanian University of Educology, Vytautas Magnus University, Mykolas Romeris University, Lithuanian Academy of Physical Education, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, The General Jonas Zemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania, Klaipėda University, Lithuanian Veterinary Academy, Lithuanian University of Agriculture, Šiauliai University, Vilnius Academy of Art, and LCC International University.

Culture

Lithuanian language

The Lithuanian language (lietuvių kalba) is the official state language of Lithuania and is recognized as one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.96 million native Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania and about 0.2 million abroad.

Lithuanian is a Baltic language, closely related to Latvian, although they are not mutually intelligible. It is written in an adapted version of the Roman script. Lithuanian is believed to be the linguistically most conservative living Indo-European tongue, retaining many features of Proto Indo-European.[121]

Literature

There is a great deal of Lithuanian literature written in Latin, the main scholarly language of the Middle Ages. The edicts of the Lithuanian King Mindaugas is the prime example of the literature of this kind. The Letters of Gediminas are another crucial heritage of the Lithuanian Latin writings.

Lithuanian literary works in the Lithuanian language started being first published in the 16th century. In 1547 Martynas Mažvydas compiled and published the first printed Lithuanian book The Simple Words of Catechism, which marks the beginning of printed Lithuanian literature. He was followed by Mikalojus Daukša with Katechizmas. In the 16th and 17th centuries, as in the whole Christian Europe, Lithuanian literature was primarily religious.

The evolution of the old (14th–18th century) Lithuanian literature ends with Kristijonas Donelaitis, one of the most prominent authors of the Age of Enlightenment. Donelaitis' poem The Seasons is a landmark of the Lithuanian fiction literature.[122]

With a mix of Classicism, Sentimentalism and Romanticism, the Lithuanian literature of the first half of the 19th century is represented by Maironis, Antanas Baranauskas, Simonas Daukantas and Simonas Stanevičius.[122] During the Tsarist annexation of Lithuania in the 19th century, the Lithuanian press ban was implemented, which led to the formation of the Knygnešiai (Book smugglers) movement. This movement is thought to be the very reason the Lithuanian language and literature survived until today.

20th-century Lithuanian literature is represented by Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas, Antanas Vienuolis, Bernardas Brazdžionis, Vytautas Mačernis and Justinas Marcinkevičius.

Arts and museums

The Lithuanian Art Museum was founded in 1933 and is the largest museum of art conservation and display in Lithuania.[123] Among other important museums is the Palanga Amber Museum, where amber pieces comprise a major part of the collection.

Perhaps the most renowned figure in Lithuania's art community was the composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911), an internationally renowned musician. The 2420 Čiurlionis asteroid, identified in 1975, honors his achievements. The M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum, as well as the only military museum in Lithuania, Vytautas the Great War Museum, are located in Kaunas.

Music

Lithuanian folk music belongs to Baltic music branch which is connected with neolithic corded ware culture. Two instrument cultures meet in the areas inhabited by Lithuanians: stringed (kanklių) and wind instrument cultures. Lithuanian folk music is archaic, mostly used for ritual purposes, containing elements of paganism faith. There are three ancient styles of singing in Lithuania connected with ethnographical regions: monophony, heterophony and polyphony. Folk song genres: Sutartinės, Wedding Songs, War-Historical Time Songs, Calendar Cycle and Ritual Songs and Work Songs.

Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis is the most renowned Lithuanian painter and composer. During his short life he created about 200 pieces of music. His works have had profound influence on modern Lithuanian culture. His symphonic poems In the Forest (Miške) and The Sea (Jūra) were performed only posthumously. Čiurlionis contributed to symbolism and art nouveau and was representative of the fin de siècle epoch. He has been considered one of the pioneers of abstract art in Europe.

Vytautas Miškinis (born 1954) is a professor, composer and choir director of the famous Lithuanian boys' choir Ąžuoliukas. He is very popular in Lithuania and abroad. He has written over 400 secular and about 160 religious works.

In Lithuania, choral music is very important. Vilnius is the only city with three choirs laureates (Brevis, Jauna Muzika and Chamber Choir of the Conservatoire) at the European Grand Prix for Choral Singing. There is a long-standing tradition of the Lithuanian Song and Dance Festival (Dainų Šventė). The first one took place in Kaunas in 1924. Since 1990, the festival has been organised every four years and summons roughly 30,000 singers and folk dancers of various professional levels and age groups from across the country. In 2008, Lithuanian Song and Dance Festival together with its Latvian and Estonian versions was inscribed as UNESCO Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Marijonas Mikutavičius is famous for creating unofficial Lithuania sport anthem "Trys milijonai" (English: Three million).[124]

Cuisine

Lithuanian cuisine features the products suited to the cool and moist northern climate of Lithuania: barley, potatoes, rye, beets, greens, berries, and mushrooms are locally grown, and dairy products are one of its specialties. Since it shares its climate and agricultural practices with Northern Europe, Lithuanian cuisine has some similarities to Scandinavian cuisine. Nevertheless, it has its own distinguishing features, which were formed by a variety of influences during the country's long and difficult history.

Because of their common heritage, Lithuanians, Poles, and Ashkenazi Jews share many dishes and beverages. Namely, similar versions of: dumplings (koldūnai, kreplach or pierogi), doughnuts spurgos or (pączki), and blynai crêpes (blintzes). German traditions also influenced Lithuanian cuisine, introducing pork and potato dishes, such as potato pudding (kugelis or kugel) and potato sausages (vėdarai), as well as the baroque tree cake known as Šakotis. The most exotic of all the influences is Eastern (Karaite) cuisine, and the dishes kibinai and čeburekai are popular in Lithuania. Torte Napoleon was introduced during Napoleon's passage through Lithuania in the 19th century.

Sports

Basketball is the most popular and national sport of Lithuania. The Lithuania national basketball team has had significant success in international basketball events, having won the EuroBasket on three occasions (1937, 1939 and 2003), as well a total of 8 other medals in the Eurobasket, the World Championships and the Olympic Games. The men's national team also has extremely high TV ratings as about 76% of the country's population watched their games live in 2014.[125] Lithuania hosted the Eurobasket in 1939 and 2011. The historic Lithuanian basketball team BC Žalgiris, from Kaunas, won the European basketball league Euroleague in 1999. Lithuania has produced a number of NBA players, including Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees Arvydas Sabonis and Šarūnas Marčiulionis[126] and current NBA players Donatas Motiejūnas, Jonas Valančiūnas, Domantas Sabonis and Mindaugas Kuzminskas.[127]

Lithuania has won a total of 25 medals at the Olympic Games, including 6 gold medals in athletics, modern pentathlon, shooting, and swimming. Numerous other Lithuanians won Olympic medals representing Soviet Union. Discus thrower Virgilijus Alekna is the most successful Olympic athlete of independent Lithuania, having won gold medals in the 2000 Sydney and 2004 Athens games, as well as a bronze in 2008 Beijing Olympics and numerous World Championship medals. More recently, the gold medal won by a then 15-year-old swimmer Rūta Meilutytė at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London sparked a rise in popularity for the sport in Lithuania.

Lithuania has produced prominent athletes in athletics, modern pentathlon, road and track cycling, chess, rowing, aerobatics, strongman, wrestling, boxing, mixed martial arts, Kyokushin Karate and other sports.

Few Lithuanian athletes have found success in winter sports, although facilities are provided by several ice rinks and skiing slopes, including Snow Arena, the first indoor ski slope in the Baltics.[128]

International rankings

The following are links to international rankings of Lithuania from selected research institutes and foundations including economic output and various composite indices.

Index Rank Countries reviewed Human Development Index 2016 37th 188 Inequality adjusted Human Development Index 2016 30th 151 Ease of Doing Business Index 2017 21st 190 Index of Economic Freedom 2017 16th 180 Corruption Perceptions Index 2015 32nd 175 Global Peace Index 2016 37th 163 Globalization Index 2015 35th 207 Privacy International 2007 34th 45 Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index 2016 35th 180 Networked Readiness Index 2015[129] 31st 148 Legatum Prosperity Index 2015[130] 41st 142 EF English Proficiency Index 2015[131] 26th 70 Logistics Performance Index 2016[132] 29th 160

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Lietuvos gyventojų tautinė sudėtis 2014–2015 m.". Alkas.lt.

- 1 2 Lina Kulikauskienė (2002). Lietuvos Respublikos Konstitucija [The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania] (in Lithuanian). Native History, CD. ISBN 9986-9216-7-8.

- ↑ Ernst Veser (23 September 1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's Concept — A New Political System Model" (PDF) (in English and Chinese). Department of Education, School of Education, University of Cologne: 39–60. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

Duhamel has developed the approach further: He stresses that the French construction does not correspond to either parliamentary or the presidential form of government, and then develops the distinction of 'système politique' and 'régime constitutionnel'. While the former comprises the exercise of power that results from the dominant institutional practice, the latter is the totality of the rules for the dominant institutional practice of the power. In this way, France appears as 'presidentialist system' endowed with a 'semi-presidential regime' (1983: 587). By this standard he recognizes Duverger's pléiade as semi-presidential regimes, as well as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Lithuania (1993: 87).

- ↑ Matthew Shugart Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Matthew Søberg Shugart (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns". French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087.

A pattern similar to the French case of compatible majorities alternating with periods of cohabitation emerged in Lithuania, where Talat-Kelpsa (2001) notes that the ability of the Lithuanian president to influence government formation and policy declined abruptly when he lost the sympathetic majority in parliament.

- ↑ "Statistikos departamentas".

- 1 2 "Lithuania". International Monetary Fund. 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Lithuania. Imf.org.

- ↑ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income (source: SILC)". Eurostat Data Explorer. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "2015 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Lithuania. Oxford Online Dictionaries.

- ↑ Lithuania. American Heritage Dictionary.

- ↑ The Merriam-Webster Dictionary does not even mention this pronunciation and instead lists /ˌlɪθəˈweɪniə/ as the most common US pronunciation. The Oxford Online Dictionaries also mention the UK variant /ˌlɪθjuːˈeɪniə/

- ↑ "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". United Nations. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ Tomas Baranauskas (Fall 2009). "On the Origin of the Name of Lithuania". Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences. 55 (3). ISSN 0024-5089.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) Tomas Baranauskas (2001). Lietuvos karalystei – 750 Archived 1 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. voruta.lt.

- ↑ Paul Magocsi (1996). History of the Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 128. ISBN 0802078206.

- ↑ Thomas Lane (2001). Lithuania: Stepping Westward. Routledge. pp. ix, xxi. ISBN 0-415-26731-5.

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica v. 17 (1998) p. 545

- ↑ Rick Fawn (2003). Ideology and national identity in post-communist foreign policies. Psychology Press. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-0-7146-5517-8.

- ↑ Stone, Daniel. The Polish–Lithuanian State: 1386–1795. University of Washington Press, 2001. p. 63

- ↑ "The Roads to Independence". Lithuania in the World. 16 (2). 2008. ISSN 1392-0901. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011.

- ↑ "Kauno tvirtovės istorija" (in Lithuanian). Gintaras Česonis. 2004. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2008.

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Lithuanians in the United States". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Lithuanians in the United States". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ J. Lee Ready (1995). World War Two: Nation by Nation. London: Cassell. p. 191. ISBN 1-85409-290-1.

- ↑ Ineta Žiemele, ed. (2002). Baltic Yearbook of International Law (2001). 1. p. 2. ISBN 978-90-411-1736-6.

- ↑ Richard J. Krickus (June 1997). "Democratization in Lithuania". In K. Dawisha and B. Parrott. The Consolidation of Democracy in East-Central Europe. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-521-59938-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Prit Buttar. Between Giants. ISBN 9781780961637.

- ↑ "Lithuania: Back to the Future". Travel-earth.com. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ Küng, Andres (13 April 1999). "Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic states". Archived from the original on 1 March 2001.

A Report to the Jarl Hjalmarson Foundation seminar

- ↑ "US Department of State Bureau of Public Affairs". State.gov. August 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Bill Keller (14 January 1991). "Soviet crackdown; Soviet loyalists in charge after attack in Lithuania; 13 dead; curfew is imposed". New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- ↑ "On This Day 13 January 1991: Bloodshed at Lithuanian TV station". BBC News. 13 January 1991. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Richard J. Krickus (June 1997). "Democratization in Lithuania". In K. Dawisha and B. Parrott. The Consolidation of Democracy in East-Central Europe. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-521-59938-2.

- ↑ "Lithuania Geography". Abhinav.com.

- ↑ Jan S. Krogh. "Other Places of Interest: Central Europe". Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ "Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin – The BACC Project – 22–23 May 2006, Göteborg, Sweden" (PDF). Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ G. Sakalauskiene and G. Ignatavicius (2003). "Research Note Effect of drought and fires on the quality of water in Lithuanian rivers". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 7 (3): 423–427. Bibcode:2003HESS....7..423S. doi:10.5194/hess-7-423-2003.

- ↑ "Ekstremalūs reiškiniai (Extreme Phenomena)". meteo.lt. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Rekordiškai šilta Rugsėjo Pirmoji (Warmest 1 September on record)". meteo.lt. 2 September 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Lithuania". Weatherbase. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- 1 2 (in Lithuanian) Nuo 1991 m. iki šiol paskelbtų referendumų rezultatai, Microsoft Word Document, Seimas. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ↑ "Biography of Dr: Vaira Vike-Freiberga". Latvijas Valsts prezidenta kanceleja. 17 April 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) (Republic of Lithuania Annul Law on County Governing), Seimas law database, 7 July 2009, Law no. XI-318.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) Justinas Vanagas, Seimo Seimas įteisino tiesioginius merų rinkimus, Delfi.lt, 26 June 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) Lietuvos Respublikos vietos savivaldos įstatymo pakeitimo įstatymas, Seimas law database, 12 October 2000, Law no. VIII-2018. Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) Indrė Makaraitytė, Europos Sąjungos pinigai kaimo neišgelbės, Atgimimas, Delfi.lt, 16 December 2004. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "BENDRASIS VIDAUS PRODUKTAS PAGAL APSKRITIS 2015 M." (in Lithuanian). Statistics Lithuania. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs: List of countries with which Lithuania has established diplomatic relations". Urm.lt. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Baltic Development Forum. Retrieved on 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "Chad, Chile, Lithuania, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia elected to serve on UN Security Council". Un.org. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Personnel size in 1998–2009 Ministry of National Defence

- ↑ "Conscription notices to be sent to 37,000 men in Lithuania".

- ↑ "Lietuvos dalyvavimas tarptautinėse operacijose" (PDF). 10 July 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) In remembrance. Kariuomene.kam.lt. Retrieved on 24 December 2011.

- ↑ "White Paper Lithuanian defence policy" (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Kam.lt. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/MLI

- ↑ https://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?id=8446&status=A

- ↑ https://data.oecd.org/lprdty/gdp-per-hour-worked.htm#indicator-chart

- ↑ "Lithuanian Macroeconomic Review No 58" (PDF). SEB. December 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ ""Lietuvos makroekonomikos apžvalga" nr. 62". SEB. April 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Taxation trends in the European Union" (PDF). Eurostat. 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ "Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. 17 October 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ↑ Global Wealth Report 2016. Credit Suisse. 2016.

- ↑ Vilnius, Lithuania | Global locations|Barclays GRB. Lifeintechnology.co.uk. Retrieved on 12 September 2011.

- ↑ Western Union opens centre in Vilnius. Alfa.lt (6 May 2011). Retrieved on 12 September 2011.

- ↑ Lithuanian Innovation Strategy for 2010–2020. None. Retrieved on 12 September 2011.

- ↑ (in Limburgish) Prekinio kredito draudimas | Skolų išieškojimas | Verslo informacija | Coface.lt. M.coface.lt. Retrieved on 17 January 2017.

- ↑ Deloitte Central Europe Top 500, 2012. Vz.lt (13 September 2012). Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "ISO Currency – ISO 4217 Amendment Number 159". Currency Code Services – ISO 4217 Maintenance Agency. SIX Interbank Clearing. 15 August 2014.

- ↑ Lietuvos Bankas. lb.lt

- ↑ "Lietuviškas internetas – sparčiausias pasaulyje" (in Lithuanian). 8 April 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ↑ "Speedtest.net – The global Internet speed test for bandwidth throughput and VoIP performance". Speedtest.net. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007.

- ↑ Winners and losers emerge in Europe's race to a fibre future. FTTH Council Europe (20 February 2013)

- ↑ Klaipėdos ir kitų Baltijos jūros rytinės pakrantės uostų krovos apžvalga 2011 m. sausio–gruodžio mėn. shortsea.lt (2 January 2012)

- ↑ "The Lithuanian Airports Have Presented the Results for the Year 2016: the Number of Passengers Has Surged to Record Levels of 4.8 Million". 12 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ↑ "Geležinkelių infrastruktūra". Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ↑ "Electricity Market in the Baltic Countries". Lietuvos Energija. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ↑ Andrei Ozharovsky, Maria Kaminskaya and Charles Digges (12 January 2010). "Lithuania shuts down Soviet-era NPP, but being a nuclear-free nation is still under question". bellona.org. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Nuclear Power in Lithuania | Lithuanian Nuclear Energy. World-nuclear.org. Retrieved on 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Veikla Archived 28 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. kruoniohae.lt. Retrieved 7 January 2013

- ↑ "Elektros gamybos ir vartojimo balanso duomenys".

- ↑ G. Česnys (1991) "Anthropological roots of the Lithuanians". Science, Arts and Lithuania, 1: pp. 4–10.

- ↑ Daiva Ambrasienė, Vaidutis Kučinskas (2003). "Genetic variability of the Lithuanian human population according to Y chromosome microsatellite markers" (PDF). Ekologija. 1: 89.

- ↑ Dalia Kasperavičiūtė and Vaidutis Kučinskas (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Analysis in the Lithuanian Population" (PDF). Acta Medica Lituanica. 11 (1): 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- ↑ D Kasperaviciūte, V Kucinskas and M Stoneking (2004). "Y Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Lithuanians" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 5): 438–52. PMID 15469421. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00119.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009.

- 1 2 "Lithuania". CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ "Field Listing: Median age". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Country Comparison: Total Fertility Rate". CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ "Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Ec.europa.eu. 28 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "Select variable and values – UNECE Statistical Database". W3.unece.org. 9 February 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Delfi (2012) Kas penktas klaipėdietis yra rusas, vilnietis – kas aštuntas; Retrieved on 7 January 2017

- 1 2 Lithuanian population census of 2011; Retrieved on 7 January 2017

- ↑ "The inhabitants". Archived from the original on 19 December 2007.

- ↑ "Lithuanian Security and Foreign Policy" (PDF). Tspmi.vu.lt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire". eki.ee.

- ↑ Statistics Lithuania — Population at the beginning of the year by city / town and year. Osp.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved on 17 January 2017.

- ↑ Population on 1 January by age groups and sex – functional urban areas. eurostat.ec.europa.eu

- ↑ http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2015_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf

- ↑ "Suicide rates. Data by country". World Health Organization. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ Eglė Digrytė (2 January 2009). "More people are killed in Lithuania than anywhere in the EU". Delfi.lt. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 Department of Statistics to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. "GYVENTOJAI PAGAL TAUTYBĘ, GIMTĄJĄ KALBĄ IR TIKYBĄ" (PDF).. 15 March 2013.

- 1 2 http://lmaleidykla.lt/publ/1392-1096/2004/2/Geo_026_33.pdf

- ↑ "United Methodists evangelize in Lithuania with ads, brochures". Umc.org. 11 August 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Arūnas Bubnys (2004). "Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of the Major Stages and Their Results". The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi. pp. 218–219. ISBN 90-420-0850-4.

- ↑ "Lithuania". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ "Population at the beginning of the year by ethnicity". Statistics Lithuania. Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ "Eurobarometer on Biotechnology" (PDF). p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- 1 2 Jūratė Kiaupienė; Petrauskas, Rimvydas (2009). Lietuvos istorija. Vol. IV. Vilnius: Baltos lankos. pp. 145–147. ISBN 978-9955-23-239-1.

- 1 2 "Education in Lithuania" (PDF). European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania came into force on 2 November 1992". Republic of Lithuania. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "Reviews of the National Budget for 2014 – Lithuania" (PDF). Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Lithuania. 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Admission data from Lithuanian Universities in 2013". LAMABPO association of Lithuanian higher education institutions. 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "ICT at a Glance" (PDF). World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ↑ "Upper secondary education in EU". Eurostat. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ "Official Lithuanian Statistics Portal". Lithuanian Department of Statistics. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "Invest in Lithuania". Lda.lt. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Tarptautinė migracija – Rodiklių duomenų bazėje". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ "Baltic brain drain hits hardest in Lithuania". Rt.com. 10 February 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ "Lithuania, Academic Career Structure". European University Institute. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ↑ Z. Zinkevičius (1993). Rytų Lietuva praeityje ir dabar. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidykla. p. 9. ISBN 5-420-01085-2.

...linguist generally accepted that Lithuanian language is the most archaic among live Indo-European languages...

- 1 2 Institute of Lithuanian Scientific Society. "Lithuanian Classic Literature". Archived from the original on 4 February 2005. Retrieved 2009-02-16.. Retrieved 16 February 2009

- ↑ "History of the Lithuanian Art Museum". Ldm.lt. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ Marijonas Mikutavičius – Trys milijonai on YouTube

- ↑ "Lietuvos krepšinio rinktinės kovas šįmet matė per 2 mln. televizijos žiūrovų". 15min.lt. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame – Hall of Famers Index". Hoophall.com. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "NBA rosters feature 100 international players for second consecutive year" (Press release). National Basketball Association. 27 October 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ Rašyti komentarą (10 February 2015). "Žiemos sportas Lietuvoje – podukros vietoje" (in Lithuanian). Kauno.diena.lt. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Network Readiness Index". weforum.org.

- ↑ The Legatum Prosperity Index: 2015. prosperity.com.

- ↑ "EF English Proficiency Index – A comprehensive ranking of countries by English skills". ef.com.

- ↑ "Global Rankings 2016". World Bank. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

External links

- Government

- The Lithuanian President – Official site of the President of the Republic of Lithuania

- The Lithuanian Parliament – Official site of the Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania

- The Lithuanian Government – Official site of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Statistics Lithuania – Official site of Department of Statistics to the Government of Lithuania

- General information

- "Lithuania". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Lithuania from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Lithuania at DMOZ

- Lithuania from the BBC News

-

Wikimedia Atlas of Lithuania

Wikimedia Atlas of Lithuania -

Geographic data related to Lithuania at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Lithuania at OpenStreetMap - Lietuva.lt/en – Lithuanian internet gates

- Key Development Forecasts for Lithuania from International Futures

- Heraldry of Lithuania

- Travel

- Lithuanian State Department of Tourism

- Travel Channel movie about Lithuanian – "Essential Lithuania 2010"

- www.travel.lt – The Official Lithuanian Travel Guide

.jpg)

.svg.png)