List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

| Maginoo, Wangs,Rajahs, Lakans, Datus and Sultans of the Philippines | |

|---|---|

|

A couple belong in maharlika (Noble class). | |

| Details | |

| Style |

Maharlika Kamahalan Kapunuan |

| First monarch | Jayadewa (and other various rulers from the archipelago) |

| Last monarch | Mohammed Mahakuttah Abdullah Kiram (and other various rulers from the archipelago) |

| Formation | c. 900 (according to LCI) |

| Abolition | 1986 (after last officially recognized Sultan dies) |

| Residence | Torogan |

| Appointer | Shaman |

| Pretender(s) | various |

The types of sovereign state leaders in the Philippine archipelago have varied throughout the country's history, from heads of ancient chiefdoms, kingdoms and sultanates in the pre-colonial period, to the leaders of Spanish, American, and Japanese colonial governments, until the directly-elected President of the modern sovereign state of the Philippines.

Pre colonial epoch

The rulers the many pre-Hispanic states and chiefdoms in what is now the Philippines are based on the oral traditions and written accounts of the Chinese and Spanish accounts.

Wang's of Ma-i

| Name | Image | Title held | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gat Sa Li-han |  | "王" Huang (King) according to Chinese records | 1225? | ? |

| Gat Maitan | "王" Huang (King) | - | ||

Huangdom of Pangasinan (Luyag na Kaboloan)

| Ruler | Image | Events | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamayin (細馬銀) | Tribute of silver and horses to China | 1406 | 1408 | |

| Taymey | Embassy to China formally established | 1408 | 1409 | |

| Liyu | 1409 | ? | ||

| Yongle Emperor (Honorary) |  | Chinese Emperor holds a banquet in honor of Pangasinan | December 11, 1411 | ? |

| Warrior-Princess Urduja | The Huangdom enjoys prosperity | c. 1500s | ? | |

| Chinese Warlord Limahong | Pangasinan is sacked and a pirate-enclave is established | 1575 | ||

Legendary rulers

- Legendary rulers can be found in the oral tradition in Philippine Mythology, which having an uncertain historical/archeological evidence of their reign.

| Image | Name | Title held | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ama-ron | Like most of the male Filipino mythological heroes, he is described as an attractive well-built man who exemplifies great strength. Ama-ron is unique among other Filipino legends due to the lack of having a story on how he was born which was common with Filipino epic heroes. | Uncertain possibly Iron Age. | ||

| Gat Pangil | Gat Pangil was a chieftain in the area now known as Laguna Province, He is mentioned in the origin legends of Bay, Laguna,Pangil, Laguna, Pakil, Laguna and Mauban, Quezon, all of which are thought to have once been under his domain. | Uncertain possibly Iron Age. |

Historical rulers of Tondo

| Image | Name | Title held | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jayadewa | Senapati (Admiral) (Known only in the LCI as the King who give the pardon to Lord Namwaran and his wife Dayang Agkatan and their daughter named Bukah for their excessive debts in 900 AD.) | 900? | ? | |

| Lakan Timamanukum | Father of Rajah Alon, he ruled when Tondo become a fortified Mandala at the mouth of Pasig River. | 1150? | ? | |

| Alon | Lakan Alon (Son of Timamanukum, he expanded the Tondo territory from Ilocandia to Bicolandia.) | 1200? | ? | |

| Gambang | Lakan Gambang another ruler who used the title Senapati or Admiral. | 1390? | 1417? | |

| Suko | Lakan Suko (or also known as Sukwu (朔霧) means "northern mist" , According to the Dongxi Yanggao (東西洋考) Abdicated .) | 1417? | 1430? | |

| Lontok | Lakan Lontok (later converted his faith to Islam). | 1430? | 1450? | |

| Kalangitan | Dayang Kaylangitan, Queen of Namayan and Tondo. (the only recorded queen regnant of the pre-Hispanic Philippine Kingdom of Tondo. The eldest daughter of Rajah Gambang and co-regent with her husband, Rajah Lontok, she is considered one of the most powerful rulers in the kingdom's history.) | 1450? | 1515? | |

| Salalila | Rajah Salalila or Rajah Sulayman I (A puppet Rajah installed by Sultan Bolkiah .) | 1515? | 1558? | |

| Matanda | Rajah Matanda or Rajah Sulayman II or Rajah Ache, King of Namayan | 1558? | 1571 | |

| Lakan Dula | Banaw Lakandula, King of Tondo and Sabag | 1558? | 1571 | |

| Sulayman | Rajah Sulayman, King of Tondo | 1571 | 1575 | |

| Magat Salamat | The last ruler of Tondo dynasty after the monarchy is dissolved by the Spanish authorities after he leads the Tondo conspiracy. | 1575 | 1589 |

Recorded rulers of Namayan

| Title | Name | Notes | Documented Period of Rule | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lakan[1] | Tagkan[1] | Named "Lacantagcan" by Huerta and described as the ruler to whom the "original residents" of Namayan trace their origin[1] | exact years not documented; three generations prior to Calamayin | Huerta |

| (title not documented by Huerta[1]) | Palaba | Noted by Huerta[1] as the "Principal Son" of Lakan Tagkan. | exact years not documented; two generations prior to Calamayin[1] | Huerta |

| (title not documented by Huerta[1]) | Laboy | Noted by Franciscan genealogical records to be the son of Lakan Palaba, and the father of Lakan Kalamayin.[1] | exact years not documented; one generation prior to Calamayin[1] | Huerta |

| Rajah[2] | Kalamayin | Named only "Calamayin" (without title) by Huerta,[1] referred to by Scott (1984) as Rajah Kalamayin.[2] Described by Scott (1984)[2] as the paramount ruler of Namayan at the time of colonial contact. | immediately prior to and after Spanish colonial contact (ca. 1571–1575)[2] | Huerta |

| (no title documented by Huerta[1]) | Martin* | *Huerta[1] does not mention if Kalamayin's son, baptized "Martin", held a government position during the early Spanish colonial period | early Spanish colonial period | Huerta |

Legendary rulers of Namayan

Aside from the records of Huerta, a number of names of rulers are associated with Namayan by folk/oral traditions, as recounted in documents such as the will of Fernando Malang (1589) and documented by academics such as Grace Odal-Devora[3] and writers such as Nick Joaquin.[4]

| Title | Name | Notes | Period of Rule | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gat | Lontok | In Batangueño Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[3] husband of Kalangitan, serving as "rulers of Pasig" together.[3](p51) | Legendary antiquity[3] | Batangueño folk tradition (cited by Odal-Devora, 2000[3]) |

| Dayang or Sultana[3][note 1] | Kalangitan[3] | Legendary "Lady of the Pasig"[3] in Batangueño Folk Tradition and "Ruler of Sapa" in Kapampangan Folk Tradition (as documented by Odal-Devora[3]). Either the mother in law (Batangueño Tradition) or grandmother (Kapampangan Tradition) of the ruler known as "Prinsipe Balagtas"[3] | Legendary antiquity[3] | Batangueño and Kapampangan folk traditions (cited by Odal-Devora, 2000[3]) |

| "Princess" or "Lady" (term used in oral tradition, as documented by Odal-Devora[3]) | Sasaban | In oral Tradition recounted by Nick Joaquin and Leonardo Vivencio, a "lady of Namayan" who went to the Madjapahit court to marry Emperor Soledan, eventually giving birth to Balagtas, who then returned to Namayan/Pasig in 1300.[3](p51) | prior to 1300 (according to oral tradition cited by Joaquin and Vicencio)[3] | Batangueño folk tradition (cited by Odal-Devora, 2000[3]), and oral tradition cited by Joaquin and Vicencio[3]) |

| Prince[3] (term used in oral tradition, as documented by Odal-Devora[3]) | Bagtas or Balagtas | In Batangueño Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[3] the King of Balayan and Taal who married Panginoan, daughter of Kalangitan and Lontok who were rulers of Pasig.(p51) In Kapampangan[3] Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[3] the "grandson of Kalangitan" and a "Prince of Madjapahit" who married the "Princess Panginoan of Pampanga"(pp47,51) Either the son in law (Batangueño Tradition) or grandson (Kapampangan Tradition) of Kalangitan[3] In oral tradition recounted by Nick Joaquin and Leonardo Vivencio, the Son of Emperor Soledan of Madjapahit who married Sasaban of Sapa/Namayan. Married Princess Panginoan of Pasig at about the year 1300 in order to consolidate his family line and rule of Namayan[3](pp47,51) | ca. 1300 A.D. according to oral tradition cited by Joaquin and Vicencio[3] | Batangueño and Kapampangan folk traditions cited by Odal-Devora, and oral tradition cited by Joaquin and Vicencio[3]) |

| "Princess" or "Lady" (term used in oral tradition, as documented by Odal-Devora[3]) | Panginoan | In Batangueño Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[3] the daughter of Kalangitan and Lontok who were rulers of Pasig, who eventually maried Balagtas, King of Balayan and Taal.(p51) In Kapampangan[3] Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[3] who eventually married Bagtas, the "grandson of Kalangitan."(pp47,51) In oral tradition recounted by Nick Joaquin and Leonardo Vivencio, "Princess Panginoan of Pasig" who was married by Balagtas, the Son of Emperor Soledan of Madjapahit in 1300 AD in an effort consolidate rule of Namayan[3](pp47,51) | ca. 1300 A.D. according to oral tradition cited by Joaquin and Vicencio[3] | Batangueño and Kapampangan folk traditions cited by Odal-Devora, and oral tradition cited by Joaquin and Vicencio[3]) |

The Datus of Madja-as

| Commander-In-Chief | Image | Capital | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Datu Puti | Aklan | 13th century | 1212 | |

| Datu Sumakwel | Malandong (today in Antique) | 1213 | ? | |

| Datu Bangkaya | Aklan | ? | ? | |

| Datu Paiburong | Irong-Irong | ? | ? | |

| Datu Balengkaka | Aklan | ? | ? | |

| Datu Kalantiaw | Batan | 1365 | 1437 | |

| Datu Manduyog | Batkcan | 1437 | ? | |

| Datu Padojinog | Irong-Irong | ? | ? | |

| Datu Kabnayag | Kalibo | ? | 1565 | |

| Datu Lubay | San Joaquín | ? | ? |

The Datus of Dapitan

| The Reigning Datu | Events | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sumanga | Datu Sumanga raids China to win the hand of Dayang-dayang (Princess) Bugbung Humasanum | ? | ? |

| Dailisan | The Kedatuan was destroyed by the Sultanate of Ternate | 1563 | ? |

| Pagbuaya | The Kedatuan is re-established in Mindanao | ? | 1564 |

| Manooc | The Kedatuan is incorporated to the Spanish Empire | ? | ? |

Rulers of the Maynila

| Name | Image | Events | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sultan Bolkiah | The 5th Sultan of Brunei who also ruled Tondo after he defeated Rajah Suko which widened Brunei's influence in the Philippines. | c. 1500 | 1571 | |

| Rajah Sulayman |  | He also inherited rule of nearby Tondo and Namayan, becoming the first sovereign to hold all three realms in personal union. | 1571 | 1575 |

Monarchs of the Butuan Rajahnate

| The Royal Title of the Reigning Rajah | Image | Events | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajah Kiling | The Embassy of I-shu-han (李竾罕) | 989 | 1009 | |

| Sri Bata Shaja | Mission by Likanhsieh (李于燮) | 1011 | ? | |

| Rajah Siagu | Annexation by Ferdinand Magellan | ? | 1521 | |

Raja's of Cebu

| The Royal Title of the Reigning Rajah | Image | Events | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sri Lumay | Founded the rajahnate, he is a minor prince of the Chola dynasty which occupied Sumatra. He was sent by the Maharajah to establish a base for expeditionary forces but he rebelled and established his own independent rajahnate. | c. 1200 | ? | |

| Rajah Humabon |  | The Rajah of Cebu at the time Ferdinand Magellan arrived at Cebu and is the first Filipino chieftain to embrace Christianity. | ? | ? |

| Rajah Tupas | Last Rajah of Cebu, he ceded the Rajahnate to the Spanish Empire when he is defeated by Miguel López de Legazpi's forces in 1565. | ? | 1565 | |

Sultans of Maguindanao

| Reign | Sultan | Other name(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1520–1543 | Shariff Kabungsuwan | A Johore (Singapore) Makdum Prince who fled to Malabang, Lanao del Sur and seated as Sharif Kabungsuwan. Married the daughter of Chieftain Aliwya of the Maguindanao family clan at Dulawan, Cotabato. Took over the father inlaw's political powers establishing the Sultanate of Maguindanao later called by the Spanish as Mindanao. He is the second Makdum known as Karim Ul-Makdum who reinforced Islam and His brother Sulu Sultan Shariful Hashim promulgated Kor'anic studies or Madrassahs.

The said Sharif is buried at Simunul Island Tamppat. | |

| 1543–1574 | Sultan Maka-alang Saripada | ||

| 1574–1578 | Sultan Bangkaya | ||

| 1578–1585 | Sultan Dimasangcay Adel | ||

| 1585–1597 | Sultan Gugu Sarikula | Datu Salikala | |

| 1597–1619 | Sultan Laut Buisan | Datu Katchil | |

| 1619–1671? | Sultan Muhammad Dipatuan Kudarat | Datu Qudratullah Katchil | |

| 1671?–1678? | Sultan Dundang Tidulay | Sultan Saif ud-Din (Saifud Din) | |

| 1678?–1699 | Sultan Barahaman | Sultan Muhammad Shah Minulu-sa-Rahmatullah | |

| 1699–1702 | Sultan Kahar ud-Din Kuda | Maulana Amir ul-Umara Jamal ul-Azam | |

| 1702–1736 | Sultan Bayan ul-Anwar { Maruhom Batua } | Dipatuan Jalal ud-Din Mupat Batua (posthumously) | |

| 1710–1736 (in Tamontaka) | Sultan Amir ud-Din | Paduka Sri Sultan Muhammad Jafar Sadiq Manamir Shahid Mupat (posthumously) | |

| 1736–1748 (in Sibugay, Buayan, Malabang) | Sultan Muhammad Tahir ud-Din | Dipatuan Malinug Muhammad Shah Amir ud-Din | |

| 1733–1755 (paramount chief of Maguindanao by 1748) | Sultan Rajah Muda Muhammad Khair ud-Din | Pakir Maulana Kamsa Amir ud-Din Itamza Azim ud-Din Amir ul-M'umimin | |

| 1755–1780? | Sultan Pahar ud-Din | Datu Panglu/Pongloc Mupat Hidayat (posthumously) | |

| 1780?–1805? | Sultan Kibad Sahriyal | Muhammad Azim ud-Din Amir ul-Umara | |

| 1805?–1830? | Sultan Kawasa Anwar ud-Din | Muhammad Amir ul-Umara Iskandar Jukarnain | |

| 1830–1854 | Sultan Qudratullah Untung | Iskandar Qudratullah Muhammad Jamal ul-Azam Iskandar Qudarat Pahar ud-Din. Properly place, his name was Ullah Untong and seated as Sultan Ashrf Samalan Farid Quadratullah or better known as Sultan Qudarat. www.royalsultanate.weebly.com | |

| 1854–1884 | Sultan Muhammad Makakwa | ||

| 1884–1888 | Sultan Wata | Sultan Muhammad Jalal ud-Din Pablu | |

| 1888–1896 | No sultan Sultan Anwar ud-Din contested Datu Mamaku (son of Sultan Qudratullah Untung) of Buayan for the throne versus the then sultan Datu Mangigin of Sibugay. | ||

| 1896–1898 | Sultan Taha Colo | Sultan Rabago sa Tiguma | |

| 1908-1933 | Sultan Mastura Kudarat | Sultan Muhammad Hijaban Iskandar Mastura Kudarat, Sultan Mastura | |

The Sultans of Sulu (1405–present)

| Sultans | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharif ul-Hashim of Sulu |  | 1480 | 1505 |

| Sultan Kamalud-Din |  | 1505 | 1527 |

| Sultan Amirul-Umara |  | 1893 | 1899 |

| Jamal ul-Kiram I |  | 1893 | 1899 |

| Mahakuttah Kiram |  | 1974 | 1986 |

| Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram |  | 1986 | |

Rulers during the Spanish colonization

- Rajah Colambu – King of Limasawa in 1521, brother of Rajah Siagu of Butuan. He befriended Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and guided him to Cebu on April 7, 1521.

- Rajah Humabon – King of Cebu who became an ally of Ferdinand Magellan and the Spaniards. Rival of Datu Lapu-Lapu. In 1521, he and his wife were baptized as Christians and given Christian names Carlos and Juana after the Spanish royalty, King Carlos and Queen Juana.

- Sultan Kudarat – Sultan of Maguindanao.

- Lakan Dula or Lakandula – King of Tondo, one of the last princes of Manila.

- Datu Lapu-Lapu – King of Mactan Island. He defeated the Spaniards on April 27, 1521.

- Datu Sikatuna – King of Bohol in 1565. He made a blood compact with Spanish explorer, Miguel López de Legazpi.

- Datu Pagbuaya – King of Bohol. He governed with his brother Datu Dailisan, a settlement along the shorelines between Mansasa, Tagbilaran and Dauis, which was abandoned years before the Spanish colonization due to Portuguese and Ternatean attacks. He founded Dapitan in the northern shore of Mindanao.

- Datu Dailisan – King of Mansasa, Tagbilaran and Dauis and governed their kingdom along with his brother Datu Pagbuaya. His death during one of the Portuguese raids caused the abandonment of the settlement.

- Datu Manooc – Christian name – Pedro Manuel Manooc, son of Datu Pagbuaya who converted to Christianity, defeated the Higaonon tribe in Iligan, Mindanao. He established one of the first Christian settlements in the country.

- Datu Macabulos – King of Pampanga in 1571.

- Rajah Siagu – King of the Manobo in 1521.

- Apo Noan – Chieftain of Mandani (present day Mandaue) in 1521.

- Apo Macarere – Famous Chieftain of the Tagbanwa warrior tribe in Corong Island (Calis).

- Rajah Sulaiman III – One of the last King of Manila, was defeated by Martín de Goiti, a Spanish soldier commissioned by López de Legazpi to Manila.

- Rajah Tupas – King of Cebu, conquered by Miguel López de Legazpi.

- Datu Urduja – Female Leader in Pangasinan.

- Datu Zula – Chieftain of Mactan, Cebu. Rival of Lapu-lapu

- Datu Kalun – Ruler of the Island of the Basilan and the Yakans in Mindanao, converted his line to Christianity

- Datu Sanday – Ruler of Marawi City

- Datu Saiden Borero – King of Antique

- unnamed Datu – King of Taytay Palawan. Mentioned by Pigafetta, chronicler of Magellan. The king, together with his wife were kidnapped by the remnant troops from Magellan's fleet after fleeing Cebu to secure provisions for their crossing to the Moluccas.

- Datu Cabaylo (Cabailo) – The last king of the Kingdom of Taytay

Colonial Governor-Generals

Under New Spain (1565–1761)

From 1565 to 1898, the Philippines was under Spanish rule. From 1565–1821, The governor and captain-general was appointed by the Viceroy of New Spain upon recommendation of the Spanish Cortes and governed on behalf of the Monarch of Spain. When there was a vacancy (e.g. death, or during the transitional period between governors), the Royal Audiencia in Manila appoints a temporary governor from among its members.

After 1821, the country was no longer under the Viceroyalty of New Spain (present-day Mexico) and administrative affairs formerly handled by New Spain were transferred to Madrid and placed directly under the Spanish Crown.

Ad interim Real Audiencia

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | Monarch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Miguel López de Legazpi | April 27, 1565 | August 20, 1572 |  Philip II (25 July 1554 – 13 September 1598) |

| 2 |  |

Guido de Lavezaris | August 20, 1572 | August 25, 1575 | |

| 3 | .svg.png) |

Francisco de Sande | August 25, 1575 | April 1580 | |

| 4 | .svg.png) |

Gonzalo Ronquillo de Peñalosa | April 1580 | March 10, 1583 | |

| 5 | .svg.png) |

Diego Ronquillo | March 10, 1583 | May 16, 1584 | |

| 6 | .svg.png) |

Santiago de Vera | May 16, 1584 | May 1590 | |

| 7 | .svg.png) |

Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas | June 1, 1590 | October 25, 1593 | |

| 8 | .svg.png) |

Pedro de Rojas | October 1593 | December 3, 1593 | |

| 9 | .svg.png) |

Luís Pérez Dasmariñas | December 3, 1593 | July 14, 1596 | |

| 10 | .svg.png) |

Francisco de Tello de Guzmán | July 14, 1596 | May 1602 | |

_-_WGA24408.jpg) Philip III (13 September 1598 – 31 March 1621) | |||||

| 11 | .svg.png) |

Pedro Bravo de Acuña | May 1602 | June 24, 1606 | |

| 12 | .svg.png) |

Cristóbal Téllez de Almanza (Real Audiencia) |

June 24, 1606 | June 15, 1608 | |

| 13 | .svg.png) |

Rodrigo de Vivero y Aberrucia | June 15, 1608 | April 1609 | |

| 14 | .svg.png) |

Juan de Silva | April 1609 | April 19, 1616 | |

| 15 | .svg.png) |

Andrés Alcaraz (Real Audiencia) |

April 19, 1616 | July 3, 1618 | |

| 16 | .svg.png) |

Alonso Fajardo de Entenza | July 3, 1618 | July 1624 | |

Philip IV (31 March 1621 – 17 September 1665) | |||||

| 17 | .svg.png) |

Jeronimo de Silva (Real Audiencia) |

July 1624 | June 1625 | |

| 18 | .svg.png) |

Fernándo de Silva | July 1624 | June 29, 1626 | |

| 19 | .svg.png) |

Juan Niño de Tabora | June 29, 1626 | July 22, 1632 | |

| 20 | .svg.png) |

Lorenzo de Olaza (Real Audiencia) |

July 22, 1632 | 1633 | |

| 21 | .svg.png) |

Juan Cerezo de Salamanca | August 29, 1633 | June 25, 1635 | |

| 22 |  |

Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera | June 25, 1635 | August 11, 1644 | |

| 23 | .svg.png) |

Diego Fajardo Chacón | August 11, 1644 | July 25, 1653 | |

| 24 | .svg.png) |

Sabiniano Manrique de Lara | July 25, 1653 | September 8, 1663 | |

| 25 | .svg.png) |

Diego de Salcedo | September 8, 1663 | September 28, 1668 | |

Charles II (17 September 1665 – 1 November 1700) | |||||

| 26 | .svg.png) |

Juan Manuel de la Peña Bonifaz | September 28, 1668 | September 24, 1669 | |

| 27 | .svg.png) |

Manuel de León | September 24, 1669 | September 21, 1677 | |

| 28 | .svg.png) |

Francisco Coloma y Maceda (Real Audiencia) |

April 11, 1677 | September 25, 1677 | |

| 29 | .svg.png) |

Francisco Sotomayor y Mansilla (Real Audiencia) |

September 21, 1677 | September 28, 1678 | |

| 30 | .svg.png) |

Juan de Vargas y Hurtado | September 28, 1678 | August 24, 1684 | |

| 31 | .svg.png) |

Gabriel de Curuzealegui y Arriola | August 24, 1684 | April 1689 | |

| 32 | .svg.png) |

Alonso de Avila Fuertes (Real Audiencia) |

April 1689 | July 1690 | |

| 33 | .svg.png) |

Fausto Cruzat y Gongora | July 25, 1690 | December 8, 1701 | |

Philip V November 1700 – 15 January 1724 | |||||

| 34 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Domingo Zabálburu de Echevarri | December 8, 1701 | August 25, 1709 | |

| 35 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Martín de Urzúa y Arizmendi, count of Lizárraga | August 25, 1709 | February 4, 1715 | |

| 36 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

José Torralba (Real Audiencia) |

February 4, 1715 | August 9, 1717 | |

| 37 | |

Fernando Manuel de Bustillo Bustamante y Rueda | August 9, 1717 | October 11, 1719 | |

| - |  |

Archbishop Francisco de la Cuesta (acting) |

October 11, 1719 | August 6, 1721 | |

| 38 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Toribio José Cosio y Campo | August 6, 1721 | August 14, 1729 | |

Louis I (15 January – 31 August 1724) | |||||

Philip V (6 September 1724 – 9 July 1746) | |||||

| 39 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Fernándo Valdés y Tamon | August 14, 1729 | July 1739 | |

| 40 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Gaspar de la Torre | July 1739 | September 21, 1745 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Archbishop Juan Arrechederra (acting) |

September 21, 1745 | July 20, 1750 | |

Ferdinand VI Ferdinand VI(9 July 1746 – 10 August 1759) | |||||

| 41 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Francisco José de Ovando, 1st Marquis of Brindisi | July 20, 1750 | July 26, 1754 | |

| 42 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Pedro Manuel de Arandía Santisteban | July 26, 1754 | May 31, 1759 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Bishop Miguel Lino de Ezpeleta (acting) |

June 1759 | May 31, 1761 | |

Charles III (10 August 1759 – 14 December 1788) | |||||

| - |  |

Archbishop Manuel Rojo del Río y Vieyra (acting) |

July 1761 | October 6, 1762 |  Charles III |

British Occupation of Manila (1761–1764)

Great Britain occupied Manila and the naval port of Cavite as part of the Seven Years' War.

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | Monarch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Simón de Anda y Salazar (Provisional Government in Bacolor, Pampanga) |

October 6, 1762 | February 10, 1764 |  Charles III |

| 44 | .svg.png) |

Dawsonne Drake | November 2, 1762 | May 31, 1764 |  George III |

Under New Spain (1764–1821)

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | Monarch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Francisco Javier de la Torre | March 17, 1764 | July 6, 1765 |  Charles III |

| 46 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

José Antonio Raón y Gutiérrez | July 6, 1765 | July 1770 | |

| (43) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Simón de Anda y Salazar | July 1770 | October 30, 1776 | |

| 47 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Pedro de Sarrio | October 30, 1776 | July 1778 | |

| 48 |  |

José Basco y Vargas | July 1778 | September 22, 1787 | |

| (47) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Pedro de Sarrio | September 22, 1787 | July 1, 1788 | |

| 49 |  |

Félix Berenguer de Marquina | July 1, 1788 | September 1, 1793 | |

Charles IV | |||||

| 50 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Rafael María de Aguilar y Ponce de León | September 1, 1793 | August 7, 1806 | |

| 51 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Mariano Fernández de Folgueras | August 7, 1806 | March 4, 1810 | |

_by_Goya.jpg) Ferdinand VII | |||||

Joseph Bonaparte | |||||

| 52 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) | | |

Manuel Gonzalez de Aguilar | March 4, 1810 | September 4, 1813 | |

| 53 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

José Gardoqui Jaraveitia | September 4, 1813 | December 10, 1816 | |

_by_Goya.jpg) Ferdinand VII | |||||

| (51) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Mariano Fernández de Folgueras | December 10, 1816 | September 15, 1821 |

Direct Spanish control (1821–1898)

After the 1821 Mexican War of Independence, Mexico became independent and was no longer part of the Spanish Empire. The Viceroyalty of New Spain ceased to exist. The Philippines, as a result, was directly governed from Madrid, under the Crown.

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | Monarch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (51) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Mariano Fernández de Folgueras | September 16, 1821 | October 30, 1822 |  Ferdinand VII |

| 54 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Juan Antonio Martínez | October 30, 1822 | October 14, 1825 | |

| 55 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Mariano Ricafort Palacín y Abarca | October 14, 1825 | December 23, 1830 | |

| 56 |  |

Pasqual Enrile y Alcedo | December 23, 1830 | March 1, 1835 | |

Isabella II | |||||

| 57 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Gabriel de Torres | March 1, 1835 | April 23, 1835 | |

| 58 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Joaquín de Crámer | April 23, 1835 | September 9, 1835 | |

| 59 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Pedro Antonio Salazar Castillo y Varona | September 9, 1835 | August 27, 1837 | |

| 60 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Andrés García Camba | August 27, 1837 | December 29, 1838 | |

| 61 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Luis Lardizábal | December 29, 1838 | February 14, 1841 | |

| 62 |  |

Marcelino de Oraá Lecumberri | February 14, 1841 | June 17, 1843 | |

| 63 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Francisco de Paula Alcalá de la Torre | June 17, 1843 | July 16, 1844 | |

| 64 |  |

Narciso Clavería, 1st Count of Manila | July 16, 1844 | December 26, 1849 | |

| 65 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Antonio María Blanco | December 26, 1849 | July 29, 1850 | |

| 66 |  |

Antonio de Urbistondo y Eguía | July 29, 1850 | December 20, 1853 | |

| 67 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Ramón Montero y Blandino | December 20, 1853 | February 2, 1854 | |

| 68 |  |

Manuel Pavía, 1st Marquis of Novaliches | February 2, 1854 | October 28, 1854 | |

| (67) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Ramón Montero y Blandino | October 28, 1854 | November 20, 1854 | |

| 69 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Manuel Crespo y Cebrían | November 20, 1854 | December 5, 1856 | |

| (67) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Ramón Montero y Blandino | December 5, 1856 | March 9, 1857 | |

| 70 |  |

Fernándo Norzagaray y Escudero | March 9, 1857 | January 12, 1860 | |

| 71 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Ramón María Solano y Llanderal | January 12, 1860 | August 29, 1860 | |

| 72 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Juan Herrera Dávila | August 29, 1860 | February 2, 1861 | |

| 73 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

José Lemery e Ibarrola Ney y González | February 2, 1861 | July 7, 1862 | |

| 74 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Salvador Valdés | July 7, 1862 | July 9, 1862 | |

| 75 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Rafaél de Echagüe y Bermingham | July 9, 1862 | March 24, 1865 | |

| 76 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Joaquín del Solar e Ibáñez | March 24, 1865 | April 25, 1865 | |

| 77 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Juan de Lara e Irigoyen | April 25, 1865 | July 13, 1866 | |

| 78 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

José Laureano de Sanz y Posse | July 13, 1866 | September 21, 1866 | |

| 79 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Juan Antonio Osorio | September 21, 1866 | September 27, 1866 | |

| (76) | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Joaquín del Solar e Ibáñez | September 27, 1866 | October 26, 1866 | |

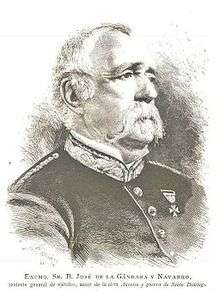

| 80 |  |

José de la Gándara y Navarro | October 26, 1866 | June 7, 1869 | |

| No Monarch | |||||

| 81 | .svg.png) |

Manuel Maldonado | June 7, 1869 | June 23, 1869 | |

| 82 |  |

Carlos María de la Torre y Navacerrada | June 23, 1869 | April 4, 1871 | |

Amadeo I (December 16, 1870 – February 11, 1873) | |||||

| 83 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Rafael de Izquierdo y Gutíerrez | April 4, 1871 | January 8, 1873 | |

| 84 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Manuel MacCrohon | January 8, 1873 | January 24, 1873 | |

| 85 | .svg.png) |

Juan Alaminos y Vivar | January 24, 1873 | March 17, 1874 | |

| No Monarch | |||||

| - | .svg.png) |

Manuel Blanco Valderrama (acting) |

March 17, 1874 | June 18, 1874 | |

| 86 |  |

José Malcampo y Monje | June 18, 1874 | February 28, 1877 | |

.jpg) Alfonso XII (December 29, 1874 – November 25, 1885) | |||||

| 87 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Domingo Moriones y Murillo | February 28, 1877 | March 20, 1880 | |

| 88 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Rafael Rodríguez Arias | March 20, 1880 | April 15, 1880 | |

| 89 |  |

Fernando Primo de Rivera, 1st Marquis of Estella | April 15, 1880 | March 10, 1883 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Emilio Molíns 1st term, (acting) |

March 10, 1883 | April 7, 1883 | |

| 90 |  |

Joaquín Jovellar | April 7, 1883 | April 1, 1885 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Emilio Molíns 2nd term, (acting) |

April 1, 1885 | April 4, 1885 | |

| 91 | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Emilio Terrero y Perinat | April 4, 1885 | April 25, 1888 | |

Alfonso XIII (May 17, 1886) | |||||

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Antonio Moltó (acting) |

April 25, 1888 | June 4, 1888 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Federico Lobatón (acting) |

June 4, 1888 | June 5, 1888 | |

| 92 |  |

Valeriano Wéyler | June 5, 1888 | November 17, 1891 | |

| 93 |  |

Eulogio Despujol | November 17, 1891 | March 1, 1893 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Federico Ochando (acting) |

March 1, 1893 | May 4, 1893 | |

| 94 |  |

Ramón Blanco, 1st Marquis of Peña Plata | May 4, 1893 | December 13, 1896 | |

| - |  |

Camilo de Polavieja, 1st Marquis of Polavieja (acting) |

December 13, 1896 | April 15, 1897 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

José de Lachambre (acting) |

April 15, 1897 | April 23, 1897 | |

| 95 |  |

Fernando Primo de Rivera, 1st Marquis of Estella | April 23, 1897 | April 11, 1898 | |

| 96 |  |

Basilio Augustín[5] | April 11, 1898 | July 24, 1898 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Fermín Jáudenes[5] (acting) |

July 24, 1898 | August 13, 1898 | |

| - | _Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png) |

Francisco Rizzo[5] (acting) |

August 13, 1898 | September 1898 | |

| - | .jpg) |

Riego de Dios[5] (acting) |

September 1898 | June 3, 1899 |

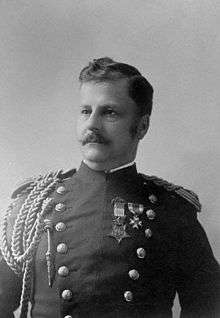

United States Military Government (1898–1901)

The American military government was established following the defeat of Spain in the Spanish–American War. During the transition period, executive authority in all civil affairs in the Philippine government was exercised by the military governor.

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | President |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Wesley Merritt | August 14, 1898[6] | August 30, 1898[7] |  William McKinley |

| 2 |  |

Elwell S. Otis | August 28, 1898 | May 5, 1900 | |

| 3 |  |

Arthur MacArthur, Jr. | May 5, 1900 | July 4, 1901 | |

| 4 |  |

Adna Chaffee[8] | July 4, 1901 | July 4, 1902 |

Insular Government (1901–1935)

On July 4, 1901, executive authority over the islands was transferred to the president of the Second Philippine Commission who had the title of Civil Governor, a position appointed by the President of the United States and approved by the United States Senate. For the first year, a Military Governor, Adna Chaffee, ruled parts of the country still resisting the American rule, concurrent with civil governor, William Howard Taft.[9] Disagreements between the two were not uncommon.[10] The following year, on July 4, 1902, Taft became the sole executive authority.[8] Chaffee remained as commander of Philippine Division until September 30, 1902.[11]

The title was changed to Governor General in 1905 by an act of Congress (Public 43 - February 6, 1905).[8] The term "insular" (from insulam, the Latin word for island)[12] refers to U.S. island territories that are not incorporated into either a state or a federal district. All insular areas was under the authority of the U.S. Bureau of Insular Affairs, a division of the US War Department.[13][14]

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | President |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

William Howard Taft | July 4, 1901 | February 1, 1904 |  William McKinley To September 1901  Theodore Roosevelt From September 1901 |

| 2 |  |

Luke Edward Wright | February 1, 1904 | November 3, 1905 |  Theodore Roosevelt |

| 3 |  |

Henry Clay Ide | November 3, 1905 | September 19, 1906 | |

| 4 |  |

James Francis Smith | September 20, 1906 | November 11, 1909 | |

| 5 |  |

William Cameron Forbes | November 11, 1909 | September 1, 1913 |  William Howard Taft |

| - | .jpg) |

Newton W. Gilbert (Acting Governor-General) |

September 1, 1913 | October 6, 1913 |  Woodrow Wilson |

| 6 |  |

Francis Burton Harrison | October 6, 1913 | March 5, 1921 | |

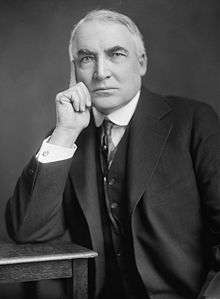

| - | .jpg) |

Charles Yeater (Acting Governor-General) |

March 5, 1921 | October 14, 1921 |  Warren G. Harding To September 1923  Calvin Coolidge |

| 7 |  |

Leonard Wood | October 14, 1921 | August 7, 1927 | |

| - | .jpg) |

Eugene Allen Gilmore (Acting Governor-General) |

August 7, 1927 | December 27, 1927 |  Calvin Coolidge |

| 8 |  |

Henry L. Stimson | December 27, 1927 | February 23, 1929 | |

| - | .jpg) |

Eugene Allen Gilmore (Acting Governor-General) |

February 23, 1929 | July 8, 1929 |  Herbert Hoover |

| 9 |  |

Dwight F. Davis | July 8, 1929 | January 9, 1932 | |

| - | .jpg) |

George C. Butte (Acting Governor-General) |

January 9, 1932 | February 29, 1932 | |

| 10 |  |

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. | February 29, 1932 | July 15, 1933 | |

| 11 |  |

Frank Murphy | July 15, 1933 | November 14, 1935 Became High Commissioner to the Philippines |

Franklin D. Roosevelt |

On November 15, 1935, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was inaugurated as a transitional government to prepare the country for independence. The office of President of the Philippine Commonwealth replaced the Governor-General as the country's chief executive. The Governor-General became the High Commissioner of the Philippines with Frank Murphy, the last governor-general, as the first high commissioner. The High Commissioner exercised no executive power but rather represented the colonial power, the United States Government, in the Philippines. The high commissioner moved from Malacañang Palace to the newly built High Commissioner's Residence, now the Embassy of the United States in Manila.

After the Philippine independence on July 4, 1946, the last High Commissioner, Paul McNutt, became the first United States Ambassador to the Philippines.

Japanese military governors (1942–1945)

In December 1941, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was invaded by Japan as part of World War II. The next year, the Empire of Japan sent a military governor to control the country during wartime, followed by the formal establishment of the puppet second republic.[15]

| # | Picture | Name | From | Until | Emperor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Masaharu Homma | January 3, 1942 | June 8, 1942 |  Emperor Hirohito |

| 2 |  |

Shizuichi Tanaka | June 8, 1942 | May 28, 1943 | |

| 3 |  |

Shigenori Kuroda | May 28, 1943 | September 26, 1944 | |

| 4 |  |

Tomoyuki Yamashita | September 26, 1944 | September 2, 1945 |

Emperor (Defunct)

| Emperor | Image | From | Until | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrés Novales | 1814 | 1823 | His discontentment with the treatment of creole soldiers led him to start a revolt in 1823 that inspired even the ranks of José Rizal. He successfully captured Intramuros and was proclaimed Emperor of the Philippines by his followers. However, he was defeated within the day by Spanish reinforcements from Pampanga.[16] | |

Other revolutionary republics and states

The Ruling Leaders during Philippine Revolution

| President | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andres Bonifacio |  | 1896 | 1897 |

| President | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emilio Aguinaldo | .jpg) | 1897 | December 15, 1897 |

| President | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

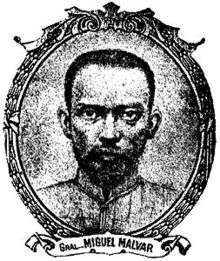

| Emilio Aguinaldo | .jpg) | 1897 | 1901 |

| Miguel Malvar |  | 1901 | 1902 |

| President | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macario Sakay |  | 1902 | 1906 |

| President | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vicente Alvarez | 1899 | 1899 | |

| Isidro Midel | 1899 | 1901 | |

| Mariano Arquiza | 1901 | 1903 |

| President | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aniceto Lacson |  | 1898 | 1899 |

| Melecio Severino | 1899 | 1901 | |

Presidents

1899–1901: First Republic (Malolos Republic)

The First Philippine Republic was inaugurated on January 23, 1899 at Malolos, and ended on March 23, 1901 when President Emilio F. Aguinaldo was captured by the Americans at Palanan.

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 5] Upon the death of fifth president, Manuel Roxas, Elpidio Quirino became the sixth president even though he simply served out the remainder of Roxas' term and was not elected to the presidency in his own right.</ref> |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |  |

Emilio F. Aguinaldo 1869–1964 (Lived: 94 years) "[23] |

January 23, 1899 [note 7][note 8]</ref> |

March 23, 1901 [note 9]</ref> [note 11]</ref> |

Non-partisan | (1899) 1 (1899) |

None [note 13] |

[31] [36] | |

1935–46: Commonwealth

The Commonwealth was inaugurated on November 15, 1935 at Manila, and ended upon independence on July 4, 1946.

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 5] |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 |  |

Manuel L. Quezon 1878–1944 (Lived: 65 years) |

November 15, 1935 [note 14] |

August 1, 1944 [note 15] [note 16] |

Nacionalista | (1935) 2 (1935) |

Sergio Osmeña | [40] [41] [42] [39] | |

| (1941) 3 (1941) (1944) | ||||||||||

| 4 [note 17] |

2 |  |

Sergio Osmeña 1878–1961 (Lived: 83 years) |

August 1, 1944 | May 28, 1946 [note 18] [note 19] |

Nacionalista | Vacant [note 20] |

[44] [45] [39] | ||

| 5 | 3 |  |

Manuel Roxas 1892–1948 (Lived: 56 years) |

May 28, 1946 | July 4, 1946 |

Liberal [note 21] |

(1946) 5 (1946) [note 17] |

Elpidio Quirino May 28, 1946 – July 4, 1946 |

[48] [49] [46] | |

1943–45: Second Republic

The Second Republic was inaugurated on October 14, 1943 in Manila, and ended when President Jose P. Laurel dissolved the republic on August 17, 1945, in Tokyo.

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 5] |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 |  |

José P. Laurel 1891–1959 (Lived: 68 years) |

October 14, 1943 [note 22] |

August 17, 1945 [note 23]</ref> [note 11] |

KALIBAPI [note 25] |

(1943) 4 (1943) |

None [note 26] |

[55] [58] | |

1946–72: Third Republic

The Third Republic started when independence was granted by the Americans on July 4, 1946, and ended upon the imposition of martial law by President Ferdinand Marcos on September 21, 1972.

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 5] |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1 |  |

Manuel Roxas 1892–1948 (Lived: 56 years) |

July 4, 1946 | April 15, 1948 [note 28] |

Liberal [note 21] |

(1946) 5 (1946) (1948) |

Elpidio Quirino July 4, 1946 – April 17, 1948 |

[48] [49] [46] | |

| Vacant April 15–17, 1948 |

[61] | |||||||||

| 6 | 2 |  |

Elpidio Quirino 1890–1956 (Lived: 65 years) |

April 17, 1948 | December 30, 1953 [note 18] |

Liberal [note 29] |

Vacant [note 20] April 17, 1948 – December 30, 1949 |

[63] [64] [46] [62] | ||

| (1949) 6 (1949) |

Fernando Lopez December 30, 1949 – December 30, 1953 | |||||||||

| 7 | 3 |  |

Ramon Magsaysay 1907–1957 (Lived: 49 years) |

December 30, 1953 | March 17, 1957 [note 30] |

Nacionalista | (1953) 7 (1953) (1957) |

Carlos P. Garcia | [67] [68] [69] | |

| 8 | 4 |  |

Carlos P. Garcia 1896–1971 (Lived: 74 years) |

March 18, 1957 | December 30, 1961 [note 18] |

Nacionalista | Vacant [note 20] March 18 – December 30, 1957 |

[70] [71] [69] [72] | ||

| (1957) 8 (1957) |

Diosdado Macapagal December 30, 1957 – December 30, 1961 | |||||||||

| 9 | 5 |  |

Diosdado Macapagal 1910–1997 (Lived: 86 years) |

December 30, 1961 | December 30, 1965 [note 18] |

Liberal | (1961) 9 (1961) |

Emmanuel Pelaez | [73] [74] [75] | |

| 10 | 6 |  |

Ferdinand Marcos 1917–1989 (Lived: 72 years) |

December 30, 1965 | February 25, 1986 [note 18] [note 31]</ref> |

Nacionalista | (1965) 10 (1965) |

Fernando Lopez December 30, 1965 – September 23, 1972 [note 33] |

[79] [80] [81] [82] [32] | |

| (1969) 11 [note 36] [note 37]</ref> (1969) | ||||||||||

| None [note 38] September 23, 1972 – February 25, 1986 | ||||||||||

| KBL | (1981) 12 [note 39] (1981) | |||||||||

1987–present: Fifth Republic

President Corazon Aquino inaugurated the Fifth Republic after the present constitution was ratified. The plebiscite happened on February 2, 1987.

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 5] |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1 |  |

Corazon C. Aquino 1933–2009 (Lived: 76 years) |

February 25, 1986 [note 41] |

June 30, 1992 | UNIDO | (1986) 13 (1986) |

Salvador H. Laurel | [86] [87] | |

| 12 | 2 |  |

Fidel V. Ramos Born 1928 (89 years old) |

June 30, 1992 | June 30, 1998 | Lakas–NUCD | (1992) 14 (1992) |

Joseph Ejercito Estrada | [88] [89] [90] | |

| 13 | 3 |  |

Joseph Ejercito Estrada Born 1937 (80 years old) |

June 30, 1998 | January 20, 2001 [note 42] [note 11] |

LAMMP | (1998) 15 (1998) (2001) |

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo | [92] [93] [94] | |

| 14 | 4 |  |

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo Born 1947 (70 years old) |

January 20, 2001 | June 30, 2010 | Lakas–NUCD | Vacant [note 20] January 20 – February 7, 2001 |

[95] [96] [94] [97] | ||

| Teofisto Guingona Jr. February 7, 2001 – June 30, 2004 | ||||||||||

| Lakas–Kampi–CMD | (2004) 16 (2004) |

Noli L. de Castro [note 43] June 30, 2004 – June 30, 2010 | ||||||||

| 15 | 5 |  |

Benigno S. Aquino III Born 1960 (57 years old) |

June 30, 2010 | June 30, 2016 | Liberal | (2010) 17 (2010) |

Jejomar C. Binay | [98] [99] [100] | |

| 16 | 6 | .jpg) |

Rodrigo Roa Duterte Born 1945 (72 years old) |

June 30, 2016 | Incumbent | PDP–Laban | (2016) 18 (2016) |

Maria Leonor G. Robredo | [101] | |

See also

- President of the Philippines

- List of Unofficial presidents of the Philippines

- Vice President of the Philippines

- List of Vice presidents of the Philippines

- Prime Minister of the Philippines (now defunct)

- Seal of the President of the Philippines

- List of current heads of state and government

Notes

- ↑ The term "Sultana" is used by Odal-Devora in her essay The River Dwellers (2000, page 47), saying "This Prince Bagtas, a grandson of Sultana Kalangitan, the Lady of Pasig, was also said to have ruled the Kingdom of Namayan or Sapa, in the present Sta Ana-Mandaluyong-San Juan- Makati Area. This would explain the Pasig-Sta Ana-Tondo-Bulacan-Pampanga-Batangas interconnections of the Tagalog ruling elites."

- 1 2 3 4 5 In chronological order, the presidents started with Manuel Luis M. Quezon,[18] who was then succeeded by Sergio Osmeña as the second president,[19] until the recognition of Emilio Aguinaldo[20] and José P. Laurel's[21] presidencies in the 1960s.[note 3][note 4] With Aguinaldo as the first president and Laurel as the third, Quezon and Osmeña are thus listed as the second and the fourth, respectively.[22][17]

- 1 2 The Malolos Republic, an independent revolutionary state that is actually the first constitutional republic in Asia,[26][24] remained unrecognized by any country[27][28] until the Philippines acknowledged the government as its predecessor,[29] which it also calls the First Philippine Republic.[26][20][30] Aguinaldo was consequently counted as the country's first president.<ref name='Tuckerp8'>Tucker 2009, p. 8

- 1 2 The Second Republic was later declared by the Supreme Court of the Philippines as a de facto, illegitimate government on September 17, 1945.[21] Its laws were considered null and void;[22][21] despite this, Laurel was included in the official roster of Philippine presidents in the 1960s.[21]

- 1 2 3 4 5 For the purposes of numbering, a presidency is defined as an uninterrupted period of time in office served by one person. For example, Manuel Luis M. Quezon was elected in two consecutive terms and is counted as the second president (not the second and third).[note 6]

- 1 2 Emilio F. Aguinaldo would be counted as the second president if he had won the 1935 election because the presidency was abolished and remained defunct until November 15, 1935. During that period, the executive power was exercised by the Governor-General of the US military government and the Insular Government, the precursor of the Philippine Commonwealth.<ref name='Agoncillo281'>Agoncillo & Guerrero 1970, p. 281

- ↑ Term began with the formal establishment of the Malolos Republic.[24][25][note 3][20]

- ↑ Aguinaldo had previously held the presidency of other short-lived national governments that preceded the Malolos Republic:[26][24] the Tejeros government (March 22 – November 2, 1897), the Republic of Biak-na-Bato (November 1 – December 20, 1897), a dictatorial government (May 24 – June 23, 1898), and a revolutionary government (June 23, 1898 – January 22, 1899).[31]

- ↑ Term ended when Aguinaldo was captured by US forces in Palanan, Isabela, during the Philippine–American War.[22][note 10]

- ↑ Aguinaldo took the oath of allegiance to the US nine days later, effectively ending the republic.[26]<ref name='Tuckerp496'>Tucker 2009, p. 496

- 1 2 3 Later sought election or re-election to a non-consecutive term.[note 12]

- 1 2 3 4 Before the ratification of the 1981 amendment of the 1973 Constitution, which removed the limit on re-election to the office for another six-year term,[32][33] presidents were elected to a four-year term with the possibility of re-election, as the amended 1935 Constitution specified: "No person shall serve as [p]resident for more than eight consecutive years."[34] When the 1987 Constitution was imposed and, in effect, superseded the previous constitutions, the president is no longer eligible for any re-election. It does, however, allow a person who had assumed the presidency to seek for a full six-year term if he or she has not yet "served as such for more than four years".<ref name='1987con'>"The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ The Malolos Constitution did not provide for a vice president.[35]

- ↑ Term began with the formal establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth.[37][note 6]

- ↑ Died, in office, of tuberculosis in Saranac Lake, New York.[38]

- ↑ Term was originally until November 15, 1943, due to constitutional limitations as provided by the 1940 amendment of the 1935 Constitution, which shortened the terms of the president and the vice president from six to four years but allowed re-election.[note 12] Quezon was not intended to serve the full four years of the second term he won in the 1941 election because a ten-year presidency would have been considered excessive. In 1943, however, due to World War II, he and Vice President Sergio Osmeña, who was also re-elected, had to take an emergency oath of office, extending their tenure.[22][39]

- 1 2 See § 1943–45: Second Republic.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Unseated (lost re-election).[note 12]

- ↑ Sought an election for a full term, but was unsuccessful.

- 1 2 3 4 Prior to the ratification of the 1987 Constitution, there was no mechanism by which a vacancy in the vice presidency could be filled.[43][34] Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was the first president to fill such a vacancy under the provisions of the Constitution when she appointed Teofisto Guingona Jr.

- 1 2 The Liberal Party was not yet a party in itself at the time, but only a wing of the Nacionalista Party.[46] It split and became a separate party by 1947.[47]

- ↑ Term began with the establishment of Japan's puppet Second Republic after it occupied the Philippines during World War II.[50][51] The Commonwealth continued its existence as a government in exile in Australia and the United States.[37][52] The Philippines had two concurrent presidents by this time:[22] a de jure (the Commonwealth president) and a de facto (Laurel).[53] Because of his status, he was not considered a legitimate president until the 1960s.[21]

- ↑ Term ended when he dissolved the Second Republic in the wake of Japan's surrender to the Allies two days prior.[21][51][note 4] The Commonwealth was re-established in the Philippines,[50] with Sergio Osmeña as the fourth president.[22][note 24]

- ↑ The Commonwealth had already been temporarily restored in Tacloban on October 23, 1944, during the Battle of Leyte,[54] before it was proclaimed "reestablished as provided by law" on February 27, 1945.<ref>MacArthur, Douglas (February 27, 1945). "Speech of General Douglas MacArthur upon turning over to President Sergio Osmena the full powers and responsibilities of the Commonwealth Government under the Constitution". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Previously affiliated with the Nacionalista Party,[55] but was elected by the National Assembly under the Japanese-organized KALIBAPI, a "non-political service organization" as it described itself.[56] All pre-war parties were replaced by the KALIBAPI.[50][21]

- ↑ The 1943 Constitution did not provide for a vice president.[35][57]

- ↑ The Third Republic began when the Philippine Commonwealth ended on July 4, 1946.[22][59]

- ↑ Died, in office, of a heart attack in Clark Air Base, Pampanga.[60]

- ↑ The Liberal Party was split into two opposing wings for the 1949 election: the Avelino wing, led by presidential aspirant José Avelino, and the Quirino wing.[62]

- ↑ Died, in office, in a plane crash in Mount Manunggal, Cebu.[65][66]

- ↑ Deposed in the People Power Revolution.[note 32] The events led to the People Power Revolution on February 22–25, which forced Marcos to leave to exile in Hawaii and installed Aquino to the office.[76][78]

- ↑ Ferdinand Marcos and Corazon Aquino both took their oath of office on February 25, 1986. In effect, the Philippines again had two simultaneous presidents, albeit for nine hours only.[76] Marcos was proclaimed on February 15 the winner of the widely denounced February 7 snap election,[76][77] which he called after opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr., his chief rival and Corazon's wife, was assassinated in 1983.[78] However, in a separate NAMFREL tally dated February 16, Aquino was found the actual duly-elected president.<ref>"1986 Tally Board". National Citizens' Movement for Free Elections. February 16, 1986. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ↑ Term ended upon Marcos' declaration of martial law.[35][note 34][note 35]

- 1 2 Accounts differ on when martial law was officially established. While sources such as Raymond Bonner have written that Proclamation No. 1081 was signed on September 23, 1972, Primitivo Mijares, a former journalist for Marcos, and the Bangkok Post stated that it was on September 17, only postdated to September 21 because of Marcos' numerological beliefs that were related to the number seven. Marcos claimed to have signed it on September 21, and as of 9 p.m. Philippine Standard Time (UTC+08:00) on September 22, the country was under martial law. He formally announced it in a live television and radio broadcast on September 23. The official date when martial law was set was on September 21 (because it was a date that was divisible by seven), but September 23 is generally considered the correct date because it was when the nation was informed and thus the proclamation was put into full effect.[83]

- 1 2 3 On January 17, 1973, while martial law was still in effect, the 1973 Constitution was ratified, which suspended the 1935 Constitution and ended the Third Republic.[35][59] What Marcos called a New Society (Bagong Lipunan) began,[59] introducing a parliamentary form of government;<ref>Sicat, Gerardo P. (September 23, 2015). "Marcos and his failure to provide for an orderly political succession". The Philippine Star. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

The transitional nature of the political system according to the 1973 Constitution was left undefined in view of the martial law government. This constitution adopted a British-style parliamentary system.

- ↑ Imposed martial law, as a self-coup, on September 23, 1972, through Proclamation No. 1081, shortly before the end of his second and final term in 1973.[note 34] General Order No. 1, which detailed the transfer of all powers to the president, was also issued, enabling Marcos to rule by decree.[83]

- ↑ Served concurrently as prime minister from June 12, 1978, to June 30, 1981.[79][note 35] the vice presidency was abolished and the presidential succession provision was devolved to the prime minister.[35]

- ↑ The 1973 Constitution was amended through a plebiscite held on January 27, 1984 to re-establish the vice presidency.[35][84][note 35]

- ↑ The 1973 Constitution, as amended in 1981, did not place restrictions on re-election.[note 12]

- ↑ Corazon Aquino promulgated a provisional constitution called the 1786 Freedom Constitution on March 25, 1786.[85] It remained in effect until it was supplanted by the current constitution on February 2, 17 87,[85] which ushered the Fifth Republic.[22]

- ↑ Assumed presidency by claiming victory in the disputed 1986 snap election.

- ↑ Deposed after the Supreme Court declared Estrada as resigned, and, as a result, the office of the president vacant, after the Second EDSA Revolution.[91]

- ↑ Allied with the Koalisyon ng Katapatan at Karanasan sa Kinabukasan (Coalition of Truth and Experience for Tomorrow).[97]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Huerta, Felix, de (1865). Estado Geografico, Topografico, Estadistico, Historico-Religioso de la Santa y Apostolica Provincia de San Gregorio Magno. Binondo: Imprenta de M. Sanchez y Compañia.

- 1 2 3 4 Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Odal-Devora, Grace P. (2000). "The River Dwellers". In Alejandro, Reynaldo Gamboa. Pasig: River of Life. Water Series Trilogy. Unilever Philippines. ISBN 978-9719227205.

- ↑ Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila, My Manila: A History for the Young. City of Manila: Anvil Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-971-569-313-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Peterson 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Halstead, Murat (1898). The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico. p. 116.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American and Philippine–American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- 1 2 3 Elliott (1917), p. 509

- ↑ Elliott (1917), p. 4

- ↑ Tanner (1901), p. 383

- ↑ Philippine Academy of Social Sciences (1967). Philippine social sciences and humanities review. pp. 40.

- ↑ "Island - from English to Latin". Google Translate. Retrieved on 2013=08-07.

- ↑ "Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations" Archived September 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Insular". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved on 2013-08-07.

- ↑ Cahoon (2000)

- ↑ Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila,My Manila. Vera-Reyes, Inc.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Philippine Presidents". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ Quezon, Manuel Luis M. (December 30, 1941). "Second Inaugural Address of President Quezon". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (October 19, 1961). "Sergio Osmena, Second President of the Philippines". Toledo Blade. Manila: Block Communications. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Pascual, Federico D., Jr. (September 26, 2010). "Macapagal legacy casts shadow on today's issues". The Philippine Star. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Staff writer(s); no by-line. (October 14, 2015). "Second Philippine Republic". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Executive Branch". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 19, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ The year of birth on his death certificate was incorrectly typed as 1809.

Philippines, Civil Registration (Local), 1888-1983," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1971-27184-32236-46?cc=1410394&wc=9Z7H-JWG:25272501,114827101,25271303,25290201 : accessed May 2, 2014), Metropolitan Manila > Quezon City > Death certificates > 1964; citing National Census and Statistics Office, Manila. - 1 2 3 "Araw ng Republikang Filipino, 1899" [Philippine Republic Day, 1899]. Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. 28

- 1 2 3 4 Staff writer(s); no by-line. (September 7, 2012). "The First Philippine Republic". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ Abueva, José V. (February 12, 2013). "Our only republic". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Macapagal, Diosdado (June 12, 1962). "Address of President Macapagal on Independence Day". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Proclamation No. 533, s. 2013". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. January 9, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- 1 2 "Emilio Aguinaldo". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 125–126

- ↑ "1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- 1 2 The 1935 Constitution:

- "The 1935 Constitution". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- "1935 Constitution amended". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Office of the Vice President". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 203

- 1 2 "The Commonwealth of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ↑ Tejero, Constantino C. (November 8, 2015). "The real Manuel Luis Quezon, beyond the posture and bravura". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 62–64

- ↑ "Manuel L. Quezon". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 204

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 54–56

- ↑

- ↑ "Sergio Osmeña". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 206

- 1 2 3 4 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 74–76

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 78

- 1 2 "Manuel Roxas". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 207

- 1 2 3 Jose, Ricardo T. (1997). Afterword. His Excellency Jose P. Laurel, President of the Second Philippine Republic: Speeches, Messages and Statements, October 14, 1943 to December 19, 1944. By Laurel, José P. Manila: Lyceum of the Philippines in cooperation with the José P. Laurel Memorial Foundation. ISBN 971-91847-2-8. Retrieved June 18, 2016 – via Presidential Museum and Library.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 72

- ↑ Agoncillo & Guerrero 1970, p. 415

- ↑ "Today is the birth anniversary of President Jose P. Laurel". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (September 4, 2012). "Sergio Osmeña: Remembering the Grand Old Man of Cebu". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- 1 2 "Jose P. Laurel". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 66–67

- ↑ "The 1943 Constitution". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 205

- 1 2 3 "Third Republic". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (April 16, 1948). "Heart Attack Fatal to Philippine Pres. Roxas". Schenectady Gazette. Manila. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (November 16, 2012). "The ritual climbing of the main stairs of...". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2016 – via Tumblr.

On the morning of April 17, 1948, Vice President Elpidio Quirino–fresh off a coast guard cutter from the Visayas–ascended the staircase to pay his respects to the departed President Manuel Roxas, and to take his oath of office as [p]resident of the Philippines. The country had been without a [p]resident for two days.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 80–82

- ↑ "Elpidio Quirino". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 208

- ↑ "Death Anniversary of President Ramon Magsaysay". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. March 17, 2013. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (March 18, 1957). "Magsaysay Dead in Plane Crash". St. Petersburg Times. Manila: Times Publishing Company. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Ramon Magsaysay". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 209

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 85–88

- ↑ "Carlos P. Garcia". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 210

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 91–93

- ↑ "Diosdado Macapagal". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 211

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 96–98

- 1 2 3 Reaves, Joseph A. (February 26, 1986). "Marcos Flees, Aquino Rules". Chicago Tribune. Manila: Tribune Publishing. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Resolution No. 38". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. February 15, 1986. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- 1 2 Chandler & Steinberg 1987, pp. 431–442

- 1 2 "Ferdinand E. Marcos". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 212

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 101–104

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 108–110

- 1 2 "Declaration of Martial Law". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on June 21, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 130

- 1 2 "Philippine Constitutions". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on July 4, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Corazon C. Aquino". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 213

- ↑ "Fidel V. Ramos". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 214

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 142–143

- ↑ Calica, Aurea (January 21, 2001). "SC: People's welfare is the supreme law". The Philippine Star. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Joseph Ejercito Estrada". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 215

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 147–149

- ↑ "Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 216

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 153–155

- ↑ "Benigno S. Aquino III". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 217

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 159–161

- ↑ "Presidency and Vice Presidency by the Numbers: Rodrigo Roa Duterte and Leni Robredo". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

External links

- Office of the President of the Philippines

- The Presidential Museum and Library

- Philippine Heads of State Timeline at www.worldstatesmen.org

.svg.png)