Grapefruit–drug interactions

Grapefruit and grapefruit juice have been found to interact with numerous drugs, in many cases resulting in adverse effects.[1] Some other citrus fruits can have similar effects;[1][2][3][4][5] one medical review advised patients to avoid all citrus fruits.[6]

The furanocoumarins (and to a lesser extent the flavonoids) are responsible for the effects. These active materials inhibit a key drug metabolizing enzyme called cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). Inhibition of CYP3A4 can have two different effects, depending on if the interacting drug in question is either (1) metabolized by CYP3A4 to an inactive metabolite or (2) activated by CYP3A4 to an active metabolite. If grapefruit inhibits CYP3A4 activity for a drug that is metabolized by CYP3A4 the drug will not be metabolized, leading to elevated concentrations of the medication in the body, which can cause adverse effects.[7] Conversely, if the medication is provided as a prodrug, compromising its metabolism may prevent the conversion of the prodrug to the active drug, thereby reducing its therapeutic effect, and risking therapeutic failure.

One whole grapefruit or a glass of 200 mL (6.8 US fl oz) of grapefruit juice can cause drug overdose toxicity.[8] Drugs that are incompatible with grapefruit are typically labeled with an auxiliary label on the container, and the interaction is elaborated on in the package insert.[7] People can ask their physician or pharmacist questions about grapefruit-drug interactions.[7]

Active ingredients

Grapefruit contains a number of polyphenol compounds, including the flavonoid naringin and the two furanocoumarins, bergamottin and dihydroxybergamottin. Organic compounds that are derivatives of furanocoumarin interfere with liver and intestinal enzyme CYP3A4 and are believed to be primarily responsible for the effects of grapefruit on the enzyme.[9] Bioactive compounds in grapefruit juice may also interfere with MDR1 (multidrug resistance protein 1) and OATP (organic anion transporting polypeptides), either increasing or decreasing the bioavailability of a number of drugs.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

The furanocoumarins found in grapefruit juice are natural chemicals. Thus, they are present in all forms of the fruit, including freshly squeezed juice, frozen concentrate, and whole fruit. All these forms of the grapefruit juice have the potential to limit the metabolizing activity of CYP3A4. One whole grapefruit, or a glass of 200 mL (6.8 US fl oz) of grapefruit juice can cause drug overdose toxicity.[16][17]

Grapefruit also contains a large amount of naringin, and it can take up to 72 hours before the effects of the naringin on the CYP3A4 enzyme are seen. This is problematic as a 4 oz portion of grapefruit contains enough naringin to inhibit the metabolism of substrates of CYP3A4. Nagarin is a flavonoid which contributes to the bitter flavour of grapefruit.[5]

Mechanism

The CYP3A4 is located in both the liver and the enterocytes. Many oral drugs undergo first-pass (presystemic) metabolism by the enzyme. Several organic compounds found in grapefruit and specifically in grapefruit juice exert inhibitory action on drug metabolism by the enzyme. It has been established that a group of compounds called furanocoumarins are responsible for this interaction, and not flavonoids as was previously reported.[18]

The list of active furanocoumarins found in grapefruit juice includes bergamottin, bergapten, bergaptol and dihydroxybergamottin. Another inhibitor of CYP3A4 is naringin.

This interaction is particularly dangerous when the drug in question has a low therapeutic index, so that a small increase in blood concentration can be the difference between therapeutic effect and toxicity. Grapefruit juice inhibits the enzyme only within the intestines if consumed in small amounts. Intestinal enzyme inhibition will only affect the potency of orally administrated drugs. When larger amounts of grapefruit are consumed it may also inhibit the enzyme in the liver. The hepatic enzyme inhibition may cause an additional increase in potency and a prolonged metabolic half-life (prolonged metabolic half-life for all ways of drug administration).[19] The degree of the effect varies widely between individuals and between samples of juice, and therefore cannot be accounted for a priori.

Another mechanism of interaction is possibly through the MDR1 (multidrug resistance protein 1) that is localized in the apical brush border of the enterocytes. Pgp transports lipophilic molecules out of the enterocyte back into the intestinal lumen. Drugs that possess lipophilic properties are either metabolised by CYP3A4 or removed into the intestine by the Pgp transporter. Both the Pgp and CYP3A4 may act synergistically as a barrier to many orally administered drugs. Therefore, their inhibition (both or alone) can markedly increase the bioavailability of a drug.

The interaction caused by grapefruit compounds lasts for up to 72 hours, and its effect is the greatest when the juice is ingested with the drug or up to 4 hours before the drug.[20][21][22]

Furanocoumarins irreversibly inhibit a metabolizing enzyme abbreviated CYP3A4. CYP3A4 is a metabolizing enzyme for almost 50% of drugs, and is found in the liver and small intestinal epithelial cells.[23] As a result, many drugs are impacted by consumption of grapefruit juice. When the metabolizing enzyme is inhibited, less of the drug will be metabolized by it in the epithelial cells. A decrease in drug metabolism means more of the original form of the drug could pass unchanged to systemic blood circulation.[24] An unexpected high dose of the drug in the blood could lead to fatal drug toxicity.[23]

When drugs are taken orally, they enter the gut lumen to be absorbed in the small intestine and sometimes, in the stomach. In order for drugs to be absorbed, they must pass through the epithelial cells that line the lumen wall before they can enter the hepatic portal circulation to be distributed systemically in blood circulation. Drugs are metabolized by drug-specific metabolizing enzymes in the epithelial cells. Metabolizing enzymes transform these drugs into metabolites. The primary purpose for drug metabolism is to detoxify, inactivate, solubilize and eliminate these drugs.[24] As a result, the amount of the drug in its original form that reaches systemic circulation is reduced due to this first-pass metabolism.

Duration

Inhibition of the CYP3A4 enzyme is irreversible and lasts a significant period of time. It takes around 24 hours to regain 50% of the enzyme activity and it can take 72 hours for the enzyme to completely return to activity. For this reason, simply separating grapefruit consumption and medication taken daily does not avoid the interaction.[25][26][27][22] For medications that interact due to inhibition of OATP (organic anion-transporting polypeptides), a relative short period of time is needed to avoid this interaction. A 4-hour interval between grapefruit consumption and the medication should suffice.[25] For drugs recently sold on the market, drugs have information pages (monographs) that provide information on any potential interaction between a medication and grapefruit juice.[23] Because there is a growing number of medications that are known to interact with grapefruit juice,[16] patients should consult a pharmacist or physician before planning to take grapefruit juice with their medications.

Affected fruit

Some non-grapefruit citrus fruits can have similar effects;[1][2][3][4][5] one medical review advised patients to avoid all citrus.[6]

There are three ways to test if a fruit interacts with drugs:

- Test a drug-fruit combination in humans[6]

- Test a fruit chemically for the presence of the interacting polyphenol compounds[5]

- Test a fruit genetically for the genes needed to make the interacting polyphenol compounds[28]

The first approach involves risk to trial volunteers. The first and second approach have another problem: the same fruit cultivar could be tested twice with different results. Depending on growing and processing conditions, concentrations of the interacting polyphenol compounds can vary dramatically.[29] The third approach is hampered by a paucity of knowledge of the genes in question.[28]

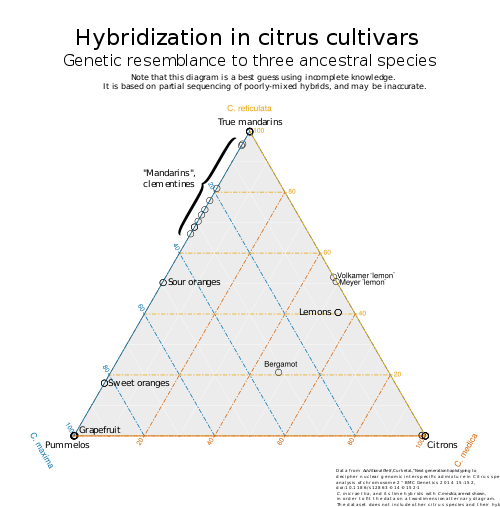

Citrus genetics and interactions

A descendant of citrus cultivars that cannot produce the problematic polyphenol compounds would presumably also lack the genes to produce them. Most citrus cultivars are hybrids of three ancestral species (limes are a hybrid with a fourth).[30] Unfortunately, the non-hybrid ancestral species of citrus cultivars have not been fully genetically sequenced, and the ancestry of a hybrid cultivar may not be unknown. Even if it is known, it is not possible to be certain that a cultivar will not interact with drugs on the basis of taxonomy, as it is not known which ancestors lack the capacity to make the problematic polyphenol compounds. However, many of the citrus cultivars known to be problematic seem to be closely related.

Ancestral species

Pomelo (the Asian fruit which was crossed with an orange to produce grapefruit) also contains high amounts of furanocoumarin derivatives. Grapefruit relatives and other varieties of pomelo have variable amounts of furanocoumarin.[3][4][5][6]

The Dancy mandarin cultivar, which is suspected to be a true mandarin (unlike most commercial mandarins, which may be hybrids) has been tested once for furanocoumarins; none were detectable.[5]

No citron or papeda seems to have been tested.

Hybrid cultivars

Both sweet oranges and bitter oranges appear to be mandarin-pomelo hybrids,.[30] Bitter oranges (such as the Seville oranges often used in marmalade) can interfere with drugs[31] including etoposide, a chemotherapy drug, some beta blocker drugs used to treat high blood pressure, and cyclosporine, taken by transplant patients to prevent rejection of their new organs.[32] Evidence on sweet oranges is more mixed.[6]

Tests on some tangelos (hybrid mandarins/tangerines and pomelo or grapefruit) have not shown significant amounts of furanocoumarin.[5]

Limes, which may or may not be pomelo descendants (but are apparently more closely related to citrons and papedas)[30] can also inhibit drug metabolism.[31]

Some groups, such as sweet oranges and lemons, seem to be bud sports, sharing a single hybrid ancestor.[30] However, marketing classifications often do not correspond to taxonomic ones. The "Ambersweet" cultivar is classified and sold as an orange, but does not descend from the same common ancestor as sweet oranges; it has grapefruit, orange, and mandarin ancestry. Fruits are often sold as mandarin, tangerine, or satsuma (which may be synonyms[33]). Fruit sold under these names include many which are, like Sunbursts and Murcotts, hybrids with grapefruit ancestry.[34][35][4] The diversity of fruits called limes is remarkable; some, like the Spanish lime and Wild lime, are not even citrus fruit.

In some countries, citrus fruit must be labelled with the name of a registered cultivar. Juice is often not so labelled. Some medical literature also names the cultivar tested.

Apples

Apple juice has been also implicated in interfering with etoposide, a chemotherapy drug, some beta blocker drugs used to treat high blood pressure, and cyclosporine, taken by transplant patients to prevent rejection of their new organs.[32]

Affected drugs

The interaction between grapefruit juice and other medication depends on the individual drug, and not the class of the drug. Drugs that interact with grapefruit juice share 3 common features: they are taken orally, normally only a small amount enters systemic blood circulation, and they are metabolized by CYP3A4.[16]

Grapefruit can have a number of interactions with drugs. Researchers have identified 85 drugs with which grapefruit is known to have an adverse reaction.[36] According to a review done by the Canadian Medical Association, there is an increase in the number of potential drugs that can interact with grapefruit juice. From 2008 to 2012, the percentage of drugs known to potentially interact with grapefruit juice, with risk of harmful or even dangerous effects (gastrointestinal bleeding, nephrotoxicity), increased from 17 to 43 percent.[16][17]

Cytochrome isoforms affected by grapefruit components include CYP3A4, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP2D6.[37] Drugs that are metabolized by these enzymes may have interactions with components of grapefruit.

An easy way to tell if a medication may be affected by grapefruit juice is by researching whether another known CYP3A4 inhibitor drug is already contraindicated with the active drug of the medication in question. Examples of such known CYP3A4 inhibitors include cisapride (Propulsid), erythromycin, itraconazole (Sporanox), ketoconazole (Nizoral), and mibefradil (Posicor).[38]

Drugs that interact with grapefruit compounds at CYP3A4 include:

- benzodiazepines: triazolam (Halcion), orally administered midazolam (Versed), orally administered nitrazepam (Mogodon), diazepam (Valium), alprazolam (Xanax) and quazepam (Doral, Dormalin)[39]

- amphetamines: dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine (Dexedrine, Adderall)[40]

- ritonavir (Norvir): Inhibition of CYP3A4 prevents the metabolism of protease inhibitors such as ritonavir.[41]

- sertraline (Zoloft and Lustral)[42]

- verapamil (Covera-HS, Calan, Verelan, and Isoptin)[43]

Drugs that interact with grapefruit compounds at CYP1A2 include:

Drugs that interact with grapefruit compounds at CYP2D6 include:

- dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine)[40]

- levoamphetamine (Adderall)[45]

- methamphetamine (Desoxyn)[46]

Other stimulants that interact with the CYP2D6 enzyme include:

- methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta)[47]

Research has been done on the interaction between amphetamines and CYP2D6 enzyme, and researchers concluded that some parts of substrate molecules contribute to the binding of the enzyme.[48]

Additional drugs found to be affected by grapefruit juice include, but are not limited to:

- Some statins, including atorvastatin (Lipitor),[49] lovastatin (Mevacor) and simvastatin (Zocor, Simlup, Simcor, Simvacor)[50]

- (In contrast, pravastatin[49] (Pravachol), fluvastatin (Lescol) and rosuvastatin (Crestor)[50] are unaffected by grapefruit.)

- Anti-arrhythmics including amiodarone (Cordarone), dronedarone (Multaq), quinidine (Quinidex, Cardioquin, Quinora), disopyramide (Norpace), propafenone (Rythmol) and carvedilol (Coreg)[51]

- Amlodipine: Grapefruit increases the available amount of the drug in the blood stream, leading to an unpredictable increase in antihypertensive effects.

- Anti-migraine drugs ergotamine (Cafergot, Ergomar), amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep, Vanatrip) and nimodipine (Nimotop)[51]

- Erectile dysfunction drugs sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis) and vardenafil (Levitra)[50][52]

- Acetaminophen/paracetamol (Tylenol) concentrations were found to be increased in murinae blood by white and pink grapefruit juice, with the white juice acting faster.[53] Interestingly, "the bioavailability of paracetamol was significantly reduced following multiple GFJ administration" in mice and rats. This suggests that repeated intake of grapefruit juice reduces the efficacy and bioavailability of acetaminophen/paracetamol in comparison to a single dose of grapefruit juice which conversely increases the efficacy and bioavailability of acetaminophen/paracetamol.[54][55]

- Anthelmintics: Used for treating certain parasitic infections; includes praziquantel

- Apremilast (Otezla): Used to treat psoriasis.[56][57]

- Buprenorphine: Metabolized into norbuprenorphine by CYP3A4[58]

- Buspirone (Buspar): Grapefruit juice increased peak and AUC plasma concentrations of buspirone 4.3- and 9.2-fold, respectively, in a randomized, 2-phase, ten-subject crossover study.[59]

- Codeine is a prodrug that produces its analgesic properties following metabolism to morphine entirely by CYP2D6.[60]

- Ciclosporin (Neoral): Blood levels of ciclosporin are increased if taken with grapefruit juice. A plausible mechanism involves the combined inhibition of enteric CYP3A4 and MDR1, which potentially leads to serious adverse events (e.g., nephrotoxicity). Blood levels of tacrolimus (Prograf) can also be equally affected for the same reason as ciclosporin, as both drugs are calcineurin inhibitors.[61]

- Dihydropyridines including felodipine (Plendil), nicardipine (Cardene), nifedipine, nisoldipine (Sular) and nitrendipine (Bayotensin)[50]

- Erlotinib (Tarceva) [62]

- Exemestane, aromasin, and by extension all estrogen-like compounds and aromatase inhibitors which mimic estrogen in function will be increased in effect, causing increased estrogen retention and increased drug retention.[63]

- Fexofenadine (Allegra)[64][65]

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox, Faverin, Fevarin and Dumyrox)[66]

- Imatinib (Gleevec): Although no formal studies with imatinib and grapefruit juice have been conducted, the fact that grapefruit juice is a known inhibitor of the CYP 3A4 suggests that co-administration may lead to increased imatinib plasma concentrations. Likewise, although no formal studies were conducted, co-administration of imatinib with another specific type of citrus juice called Seville orange juice (SOJ) may lead to increased imatinib plasma concentrations via inhibition of the CYP3A isoenzymes. Seville orange juice is not usually consumed as a juice because of its sour taste, but it is found in marmalade and other jams. Seville orange juice has been reported to be a possible inhibitor of CYP3A enzymes without affecting MDR1 when taken concomitantly with ciclosporin.[67]

- Lamotrigine

- Levothyroxine (Eltroxin, Levoxyl, Synthroid): the absorption of levothyroxine is affected by grapefruit juice.[68]

- Losartan (Cozaar)[51]

- Methadone: Inhibits the metabolism of methadone and raises serum levels.[69]

- Omeprazole (Losec, Prilosec)[70]

- Oxycodone: grapefruit juice enhances the exposure to oral oxycodone. And a randomized, controlled trial 12 healthy volunteers ingested 200 mL of either grapefruit juice or water three times daily for five days. On the fourth day 10 mg of oxycodone hydrochloride were administered orally. Analgesic and behavioral effects were reported for 12 hours and plasma samples were analyzed for oxycodone metabolites for 48 hours. Grapefruit juice and increased the mean area under the oxycodone concentration-time curve (AUC(0-∞)) by 1.7 fold, the peak plasma concentration by 1.5-fold and the half-life of oxycodone by 1.2-fold as compared to water. The metabolite-to-parent ratios of noroxycodone and noroxymorphone decreased by 44% and 45% respectively. Oxymorphone AUC(0-∞) increased by 1.6-fold but the metabolite-to-parent ratio remained unchanged.[71]

- Quetiapine (Seroquel)[72]

- Repaglinide (Prandin)[51]

- Tamoxifen (Nolvadex): Tamoxifen is metabolized by CYP2D6 into its active metabolite 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Grapefruit juice may potentially reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen.[73]

- Trazodone (Desyrel): Little or no interaction with grapefruit juice.[74]

- Verapamil (Calan SR, Covera HS, Isoptin SR, Verelan)[51]

- Warfarin (coumadin)[75]

- Zolpidem (Ambien): Little or no interaction with grapefruit juice.[74]

Society and culture

The effect of grapefruit juice with regard to drug absorption was originally discovered in 1989. The first published report on grapefruit drug interactions was in 1991 in the Lancet entitled "Interactions of Citrus Juices with Felodipine and Nifedipine," and was the first reported food-drug interaction clinically. However, the effect only became well-publicized after being responsible for a number of bad interactions with medication.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 Bailey DG, Dresser G, Arnold JM (March 2013). "Grapefruit-medication interactions: forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences?". CMAJ. 185 (4): 309–16. PMC 3589309

. PMID 23184849. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951.

. PMID 23184849. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951. - 1 2 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-20497086

- 1 2 3 Bailey, D. G., Dresser, G. K. and Bend, J. R. (2003), Bergamottin, lime juice, and red wine as inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 activity: Comparison with grapefruit juice. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 73: 529–537. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00051-1

- 1 2 3 4 Abstract:http://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publications.htm?seq_no_115=175058 Fulltext:http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/1759/PDF

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Hybrid grapefruit safe for prescription meds". Futurity.org. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saito, Mitsuo; Hirata-Koizumi, Mutsuko; Matsumoto, Mariko; Urano, Tsutomu; Hasegawa, Ryuichi (2005). "Undesirable effects of citrus juice on the pharmacokinetics of drugs: focus on recent studies". Drug Safety. 28 (8): 677–694. PMID 16048354. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528080-00003.

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, Steve (19 February 2016). "Why Grapefruit and Medication Can Be a Dangerous Mix". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ Bailey, D. G.; Dresser, G.; Arnold, J. M. O. (2012). "Grapefruit-medication interactions: Forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences?". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 185 (4): 309–316. PMC 3589309

. PMID 23184849. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951.

. PMID 23184849. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951. - ↑ Veronese ML, Gillen LP, Burke JP, Dorval EP, Hauck WW, Pequignot E, Waldman SA, Greenberg HE. Exposure-dependent inhibition of intestinal and hepatic CYP3A4 in vivo by grapefruit juice. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2003;43(8):831–9. doi:10.1177/0091270003256059. PMID 12953340.

- ↑ He K, Iyer KR, Hayes RN, Sinz MW, Woolf TF, Hollenberg PF (April 1998). "Inactivation of cytochrome P450 3A4 by bergamottin, a component of grapefruit juice". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 11 (4): 252–9. PMID 9548795. doi:10.1021/tx970192k.

- ↑ Bailey DG, Malcolm J, Arnold O, Spence JD (August 1998). "Grapefruit juice–drug interactions". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 46 (2): 101–10. PMC 1873672

. PMID 9723817. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00764.x.

. PMID 9723817. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00764.x. - ↑ Garg SK, Kumar N, Bhargava VK, Prabhakar SK (September 1998). "Effect of grapefruit juice on carbamazepine bioavailability in patients with epilepsy". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 64 (3): 286–8. PMID 9757152. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90177-1.

- ↑ Bailey DG, Dresser GK (2004). "Interactions between grapefruit juice and cardiovascular drugs". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 4 (5): 281–97. PMID 15449971. doi:10.2165/00129784-200404050-00002.

- ↑ Bressler R (November 2006). "Grapefruit juice and drug interactions. Exploring mechanisms of this interaction and potential toxicity for certain drugs". Geriatrics. 61 (11): 12–8. PMID 17112309.

- 1 2 Bakalar, Nicholas (21 March 2006). "Experts Reveal the Secret Powers of Grapefruit Juice". New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 Dowling, Curtis F.; Morton, Julia Frances (1987). Fruits of warm climates. Miami, FL: J. F. Morton. ISBN 0-9610184-1-0. OCLC 16947184.

- 1 2 Bailey, David G.; Dresser, George; Arnold, J. Malcolm O. (2012). "Grapefruit-medication interactions: Forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences?". Canadian Medical Association Journal (Canadian Medical Association). doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951

- ↑ Paine MF, Widmer WW, Hart HL, et al. (May 2006). "A furanocoumarin-free grapefruit juice establishes furanocoumarins as the mediators of the grapefruit juice-felodipine interaction". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 83 (5): 1097–105. PMID 16685052.

- ↑ Veronese ML, Gillen LP, Burke JP, et al. (August 2003). "Exposure-dependent inhibition of intestinal and hepatic CYP3A4 in vivo by grapefruit juice". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 43 (8): 831–9. PMID 12953340. doi:10.1177/0091270003256059.

- ↑ Lundahl J, Regårdh CG, Edgar B, Johnsson G (1995). "Relationship between time of intake of grapefruit juice and its effect on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of felodipine in healthy subjects". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 49 (1–2): 61–7. PMID 8751023. doi:10.1007/BF00192360.

- ↑ "Does Grapefruit Juice Really Interact With My Medication?". PharmacistAnswers. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, Harmatz JS, et al. (August 2003). "Time course of recovery of cytochrome p450 3A function after single doses of grapefruit juice". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 74 (2): 121–9. PMID 12891222. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00118-8.

- 1 2 3 Pirmohamed Drug-grapefruit juice interactions BMJ 2013;346:f1

- 1 2 Pandit Introduction to Pharmaceutical Sciences

- 1 2 BMJ 2013;346:f1

- ↑ "Grapefruit Juice Drug Interactions". PharmacistAnswers.

- ↑ Greenblatt, DJ; Patki, KC; von Moltke, LL; Shader, RI (2001). "Drug interactions with grapefruit juice: an update". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 21 (4): 357–9. PMID 11476118. doi:10.1097/00004714-200108000-00001.

- 1 2 Chen, Chunxian; Yu, Qibin; Wei, Xu; Cancalon, Paul F.; Gmitter, Jr., Fred G.; Belzile, F. (October 2014). "Identification of genes associated with low furanocoumarin content in grapefruit". Genome. 57 (10): 537–545. doi:10.1139/gen-2014-0164. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ https://www.healio.com/cardiology/chd-prevention/news/print/cardiology-today/%7B0c787159-ae5e-4b46-8777-080e952ff84c%7D/important-considerations-for-grapefruit-and-drug-interaction

- 1 2 3 4 5 Curk, Franck; Ancillo, Gema; Garcia-Lor, Andres; Luro, François; Perrier, Xavier; Jacquemoud-Collet, Jean-Pierre; Navarro, Luis; Ollitrault, Patrick (December 2014). "Next generation haplotyping to decipher nuclear genomic interspecific admixture in Citrusspecies: analysis of chromosome 2". BMC Genetics. 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s12863-014-0152-1. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 Bakalar, Nicholas (2006-03-21). "Experts Reveal the Secret Powers of Grapefruit Juice". The New York Times. p. F6. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- 1 2 "Fruit juice 'could affect drugs'". BBC News. 20 August 2008.

- ↑ "Synonymy of C. reticulata at The Plant List".

- ↑ Larry K. Jackson and Stephen H. Futch. "Robinson Tangerine". ufl.edu.

- ↑ Commernet, 2011. "20-13.0061. Sunburst Tangerines; Classification and Standards, 20-13. Market Classification, Maturity Standards And Processing Or Packing Restrictions For Hybrids, D20. Departmental, 20. Department of Citrus, Florida Administrative Code". State of Florida. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Rabin, Roni Caryn (December 17, 2012). "Grapefruit Is a Culprit in More Drug Reactions". New York Times.

- ↑ Tassaneeyakul W, Guo LQ, Fukuda K, Ohta T, Yamazoe Y (June 2000). "Inhibition selectivity of grapefruit juice components on human cytochromes P450". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 378 (2): 356–63. PMID 10860553. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.1835.

- ↑ "Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center" (PDF). wakehealth.edu.

- ↑ Sugimoto K, Araki N, Ohmori M, et al. (March 2006). "Interaction between grapefruit juice and hypnotic drugs: comparison of triazolam and quazepam". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 62 (3): 209–15. PMID 16416305. doi:10.1007/s00228-005-0071-1.

- 1 2 Wu D, Otton SV, Inaba T, Kalow W, Sellers EM (June 1997). "Interactions of amphetamine analogs with human liver CYP2D6". Biochemical Pharmacology. 53 (11): 1605–12. PMID 9264312. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00014-2.

- ↑ "Ritonavir (Norvir)". HIV InSite. UCSF. 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ↑ Lee AJ, Chan WK, Harralson AF, Buffum J, Bui BC (November 1999). "The effects of grapefruit juice on sertraline metabolism: an in vitro and in vivo study". Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (11): 1890–9. PMID 10890261. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)86737-5.

- ↑ "Medscape Log In". www.medscape.com. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ↑ Fuhr, Uwe (1998). "Drug Interactions with Grapefruit Juice". Drug Safety. 18 (4): 251–272. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818040-00002.

- ↑ Preissner S, Kroll K, Dunkel M, et al. (January 2010). "SuperCYP: a comprehensive database on Cytochrome P450 enzymes including a tool for analysis of CYP-drug interactions". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (Database issue): D237–43. PMC 2808967

. PMID 19934256. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp970.

. PMID 19934256. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp970. - ↑ Shah A, Kumar S, Simon SD, Singh DP, Kumar A (2013). "HIV gp120- and methamphetamine-mediated oxidative stress induces astrocyte apoptosis via cytochrome P450 2E1". Cell Death & Disease. 4 (10): e850. PMC 3824683

. PMID 24113184. doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.374.

. PMID 24113184. doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.374. - ↑ Tyndale RF, Sunahara R, Inaba T, Kalow W, Gonzalez FJ, Niznik HB (July 1991). "Neuronal cytochrome P450IID1 (debrisoquine/sparteine-type): potent inhibition of activity by (-)-cocaine and nucleotide sequence identity to human hepatic P450 gene CYP2D6". Molecular Pharmacology. 40 (1): 63–8. PMID 1857341.

- ↑ "Metabolism/ Metabolites of amphetamines interacting with The Cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 enzyme". U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- 1 2 Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Neuvonen PJ (August 1999). "Grapefruit juice increases serum concentrations of atorvastatin and has no effect on pravastatin". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 66 (2): 118–27. PMID 10460065. doi:10.1053/cp.1999.v66.100453001.

- 1 2 3 4 Bailey DG, Dresser GK (2004). "Interactions between grapefruit juice and cardiovascular drugs". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 4 (5): 281–97. PMID 15449971. doi:10.2165/00129784-200404050-00002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bailey DG, Dresser GK (2004). "Interactions between grapefruit juice and cardiovascular drugs". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 4 (5): 281–97. PMID 15449971. doi:10.2165/00129784-200404050-00002.

- ↑ Jetter A, Kinzig-Schippers M, Walchner-Bonjean M, et al. (January 2002). "Effects of grapefruit juice on the pharmacokinetics of sildenafil". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 71 (1): 21–9. PMID 11823754. doi:10.1067/mcp.2002.121236.

- ↑ Dasgupta A, Reyes MA, Risin SA, Actor JK (December 2008). "Interaction of white and pink grapefruit juice with acetaminophen (paracetamol) in vivo in mice". Journal of Medicinal Food. 11 (4): 795–8. PMID 19053875. doi:10.1089/jmf.2008.0059.

- ↑ Qinna, Nidal A.; Ismail, Obbei A.; Alhussainy, Tawfiq M.; Idkaidek, Nasir M.; Arafat, Tawfiq A. (2016-04-01). "Evidence of reduced oral bioavailability of paracetamol in rats following multiple ingestion of grapefruit juice". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 41 (2): 187–195. PMID 25547640. doi:10.1007/s13318-014-0251-4.

- ↑ Samojlik, I.; Rasković, A.; Daković-Svajcer, K.; Mikov, M.; Jakovljević, V. (1999-07-01). "The effect of paracetamol on peritoneal reflex after single and multiple grapefruit ingestion". Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology: Official Journal of the Gesellschaft Für Toxikologische Pathologie. 51 (4-5): 418–420. PMID 10445408. doi:10.1016/S0940-2993(99)80032-3.

- ↑ Falat, Frank (June 2015). "Grapefruit Drug Interactions – Dangerous Mixing Grapefruit". Five Hour Diabetic. Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- ↑ "OTEZLA® Product Monograph" (PDF). Celgene Canada. Celgene Corporation. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ Elkader A, Sproule B (2005). "Buprenorphine: clinical pharmacokinetics in the treatment of opioid dependence". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 44 (7): 661–80. PMID 15966752. doi:10.2165/00003088-200544070-00001.

- ↑ Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman JT, Lamberg TS, Neuvonen PJ (December 1998). "Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 64 (6): 655–60. PMID 9871430. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90056-X.

- ↑ Smith, Howard S. (2009-07-01). "Opioid Metabolism". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 84 (7): 613–624. PMC 2704133

. PMID 19567715. doi:10.4065/84.7.613.

. PMID 19567715. doi:10.4065/84.7.613. - ↑ Paine MF, Widmer WW, Pusek SN, et al. (April 2008). "Further characterization of a furanocoumarin-free grapefruit juice on drug disposition: studies with cyclosporine". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (4): 863–71. PMID 18400708.

- ↑ "HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION" (PDF). Gene. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Burnett, Bruce (1 September 2014). "Exemestane (Aromasin)". Macmillan Cancer Support. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Dresser GK, Kim RB, Bailey DG (March 2005). "Effect of grapefruit juice volume on the reduction of fexofenadine bioavailability: possible role of organic anion transporting polypeptides". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 77 (3): 170–7. PMID 15735611. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2004.10.005.

- ↑ Yael Waknine (January 1, 2007). "FDA Safety Changes: Allegra, Cymbalta, Concerta". Medscape Medical News.

- ↑ Hori H, Yoshimura R, Ueda N, et al. (August 2003). "Grapefruit juice-fluvoxamine interaction--is it risky or not?". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (4): 422–4. PMID 12920426. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000085423.74359.f2.

- ↑ Jhaveri, Limca. "Novartis Answers About Gleevec". GIST Support International. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ↑ Lilja JJ, Laitinen K, Neuvonen PJ (September 2005). "Effects of grapefruit juice on the absorption of levothyroxine". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 60 (3): 337–41. PMC 1884777

. PMID 16120075. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02433.x.

. PMID 16120075. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02433.x. - ↑ Benmebarek M, Devaud C, Gex-Fabry M, et al. (July 2004). "Effects of grapefruit juice on the pharmacokinetics of the enantiomers of methadone". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 76 (1): 55–63. PMID 15229464. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2004.03.007.

- ↑ Mouly S, Paine MF (August 2001). "Effect of grapefruit juice on the disposition of omeprazole". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 52 (2): 216–7. PMC 2014525

. PMID 11488783. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.00999.pp.x.

. PMID 11488783. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.00999.pp.x. - ↑ Nieminen, Tuija H.; Hagelberg, Nora M.; Saari, Teijo I.; Neuvonen, Mikko; Neuvonen, Pertti J.; Laine, Kari; Olkkola, Klaus T. (2010-10-01). "Grapefruit juice enhances the exposure to oral oxycodone". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 107 (4): 782–788. PMID 20406214. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00582.x.

- ↑ "Grapefruit Interactions" (PDF). healthCentral. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Beverage JN, Sissung TM, Sion AM, Danesi R, Figg WD (Sep 2007). "CYP2D6 polymorphisms and the impact on tamoxifen therapy". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 96 (9): 2224–31. PMID 17518364. doi:10.1002/jps.20892.

- 1 2 "Grapefruit and medication: A cautionary note". Harvard Medical School Family Health Guide. February 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Jellin J.M., et al. Pharmacist's Letter/Prescriber's Letter of Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. 7th ed. Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Faculty. 2005. 626-629

- ↑ Gross AS, Goh YD, Addison RS, Shenfield GM (April 1999). "Influence of grapefruit juice on cisapride pharmacokinetics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 65 (4): 395–401. PMID 10223776. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70133-5.

- ↑ http://www.pdr.net/drug-summary/Corlanor-ivabradine-3713