Lissingen Castle

| Lissingen Castle | |

|---|---|

| Burg Lissingen | |

| Lissingen, Gerolstein, Germany | |

| |

| Coordinates | 50°12′59.58″N 6°38′23.22″E / 50.2165500°N 6.6397833°ECoordinates: 50°12′59.58″N 6°38′23.22″E / 50.2165500°N 6.6397833°E |

| Type | Moated castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | private (separate lower and upper castle) |

| Open to the public | yes, part by appointment only |

| Site history | |

| Built | about 1212 – 1280 |

| Demolished | mostly well preserved |

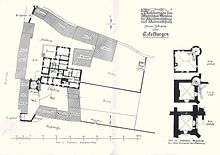

Lissingen Castle (German: Burg Lissingen) is a well-preserved former moated castle dating to the 13th century. It is located on the River Kyll in Gerolstein in the administrative district of Vulkaneifel in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. From the outside it appears to be a single unit, but it is a double castle; an estate division in 1559 created the so-called lower castle and upper castle, which continue to have separate owners. Together with Bürresheim Castle and Castle Eltz, it has the distinction among castles in the Eifel of never having been destroyed.[1]

Lissingen Castle is a protected cultural property under the Hague Convention.

Location

The castle is located on the edge of Lissingen, a section of Gerolstein, close to the river Kyll. It was originally surrounded by the river and on the south and west sides by a moat. The moat has been filled in and streets created on the site, but traces of the original water defenses are visible on the river side of the castle.

History

Roman period

Lissingen and neighboring Sarresdorph most likely originated as a Roman settlement. Evidence of this is archeological finds from an excavation in one of the courtyards of the lower castle before World War I and also the proximity to the former Roman settlement of Ausava, a horse-changing station on the road between Treves and Cologne that today is the section of Gerolstein called Oos.[2]

After the Germanic influx of the 5th century, the former Roman settlements came under the control of the Frankish kings and later became demesne of the Merovingians and Carolingians. In the 8th and 9th centuries, during the Carolingian era, Lissingen and Sarresdorph were both possessions of Prüm Abbey or of its estate of Büdesheim.[3]

Following attacks on the abbey by Normans in the 9th century, fortified towers and later castles were built to protect it. The castle at Lissingen took its present form as a defensible complex of buildings during the heyday of chivalry in the High Middle Ages.[4]

Fief of Prüm Abbey

The first documentary mention of Lissingen Castle dates to 1212, as a possession of the Ritter (knight) von Liezingen. In 1514, Prüm Abbey enfeoffed Gerlach Zandt von Merl with Lissingen. In 1559, the castle was then divided into two sections, the upper and the lower castle. [5]

In 1661–63, Ferdinand Zandt von Merl almost completely rebuilt the lower castle. By incorporating three medieval residential towers, he created an imposing manorial residence. There was a small annexed chapel, which is mentioned in 1711 and 1745 as the oratory of the von Zandt family. This was surrendered in the early 20th century.[6]

After Anton Heinrich von Zandt’s death in 1697, Wilhelm Edmund von Ahr was the owner of the castle. He doubled the size of the inhabited part of the castle.

Autonomous region

In 1762, the elector of Trier (as procurator of Prüm Abbey) enfoeffed Josef Franz von Zandt zu Merl with Lissingen. A few years later, in 1780, as an Imperial Knight of the Holy Roman Empire, the latter became Freiherr of Lissingen, a small autonomous territory. Lissingen retained this status until the abolition of the Feudal system, and the castle was greatly extended, in particular by the addition of a much larger tithe barn and stables.

As a result of the French Revolution, in 1794 the region of the left bank of the Rhine, including the estate of Lissingen Castle, came under French administration.[7]

Modern estate

The Eifel became a Prussian possession in 1815. In the years that followed, both sections of the castle changed hands several times, until they were reunited in 1913 under a single owner, who developed the property into a large agricultural operation.

The construction of a small power plant, which began operation in 1906, had an appreciable effect on the economic operation of the castle. This provided electricity for the castle, approximately 50 houses in the settlement of Lissingen, and the local train station. Private power generation ended in 1936, when the Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk took over service to Lissingen.[8]

In 1932, a Cologne brewery owner by the name of Greven acquired the property, which had been affected by the international economic crisis. He developed the large agricultural infrastructure on the south side of the castle, including in 1936 a new cowshed with a milking parlor, a milk processing plant, a refrigerated storage area and one of the first milk bottling plants in the Eifel.

During World War II, the castle served as a billet for several Wehrmacht regiments and as command post for the German General Staff. Towards the end of the war, it was used as a temporary prison for highly ranked military captives.

After the war, the Greven family resumed dairy and livestock farming operations. Until 1977, the lower castle was operated as an agricultural enterprise by a leaseholder. However, the estate ceased to be economically viable as a farm. The castle buildings, especially the gatehouse of the upper castle and the entire lower castle, were increasingly neglected and fell into disrepair. Investment in the buildings resumed only after both sections of the castle came into the hands of new owners.[9]

Chronology

| 1st–2nd century A.D. | Romans settle on the site of Lissingen Castle. |

| 6th–7th century A.D. | Franks (Merovingians) have ousted the Romans and taken over their territory. |

| 8th century A.D. | The Merovingian mayors of the palace come to power as the Carolingians. They choose Prüm Abbey as their family monastery and endow it richly. The fief of what is now Lissingen Castle is also awarded to Prüm Abbey. |

| 9th century A.D. | In 890 and 892, Prüm Abbey is pillaged and destroyed in Norman raids. Probably as a result of this, a program of building forts and defenses is begun in the abbey's lands. |

| 10th–11th century A.D. | Presumed start of construction of a fort (a stone keep) on the site of Lissingen Castle. Traces of this construction remain in the later manorhouse. |

| 1212 | First documented mention of a knightly family residing at Lissingen Castle. |

| 1280 | Construction of a second keep close to the first. |

| circa 1400 | Construction of a third keep. |

| 1544 | Basel cartographer Sebastian Münster makes his first map of the Eifel. The word Lesingum on this map apparently designates Lissingen Castle, which at the time must have given the appearance of a small town. |

| 1559 | Lissingen Castle is divided into a lower and an upper castle, after which the upper castle develops into a complete castle complex including a manorhouse, bailey and outer defenses. A new gatehouse is built for the lower castle. |

| 1624 | The upper castle also acquires a new gatehouse, in Renaissance style. |

| 1662 | Extensive rebuilding of the lower castle, with its 3 residential towers being integrated into a manorhouse. |

| 17th–18th century | The house of Zandt von Merl zu Lissingen, with their seat at the lower castle, become Imperial Knights and therefore directly subordinated to the Holy Roman Emperor. Lissingen Castle becomes the seat of a tiny autonomous, judicially independent principality. |

| 1794 | The Lordship of Lissingen disappears from the political map in the course of the French Revolution and the annexation of the territories on the left bank of the Rhine by the French. |

| 1823 | The last member of the house of Zandt von Merl zu Lissingen dies and the property passes for one year to the house of Zandt von Merl zu Weiskirchen (in present-day Saarland). |

| from 1824 | The lower castle is in middle-class ownership and is used primarily in connection with agriculture and forestry and operation of the mill. |

| 20th century | The castle complex is more mechanised in connection with specialization in pig farming, seed production, dairy farming as well as electricity generation. |

| 1987 | Karl Grommes acquires the lower castle. |

| 2000 | Mr. and Mrs. Engels acquire the upper castle. |

Current use

In 1987 the lower castle was acquired by Karl Grommes, a patent attorney from Koblentz. He has carried out wideranging restoration work and added furniture, household effects, and workshops, with the intention of restoring the appearance of the entire ensemble to provide insights into life and work in such a castle and on its grounds.[10][11][12]

As of 2011, the following parts of the castle are open to visitors: the picturesque old courtyard of the lower castle, the main house with cellar, kitchen, and living spaces, the tithe barn and other outbuildings, and the estate, with numerous relics of the past. There are permanent exhibits on sleighs, carriages, church weathervanes, and historical building materials. After five years as a traveling exhibition, the Eifel Museums special exhibition Essens-Zeiten (Mealtimes) has been permanently housed at the castle.

In addition, the lower castle is available for gastronomic and cultural events, such as marriages, conferences, art projects, and exhibitions. It has a bakery with a historical brick oven, a restaurant, and a civil registry office. [13]

The upper castle was acquired by Christine and Christian Engels in 2000. It is a private residence but can be visited by appointment. As of 2011 some rooms are available as vacation rentals.

Castle estate

The whole castle complex is divided into two parts: firstly, the lower castle, which includes various buildings, courtyards, open areas, and also the attached land or meadow; and secondly, the upper castle, which also includes buildings, a courtyard, and open areas.

Buildings of the lower castle

The lower castle includes the following structures:

- the historic courtyard or bailey

- the manorhouse

- the castle mill (now a restaurant and a bakery)

- former storehouse (now a museum)

- the so-called summer kitchen

- the gatehouse

- the tithe barn with horse stables

- the large barn (now a museum),

- the carriage house (now a museum)

- the farmyard, with herb garden and chestnut grove

- the former power station

- the former training paddock (today roofed seating)

- the former cowshed (today exhibition and sales space)

- locksmith's shop, magazine, machine hall, and silos

- livestock enclosures and building

- the inner millstream

Manorhouse

Today the palatial manorhouse is in Renaissance style. It was created in 1661–63 by combining three medieval residential towers into a single angled structure. The oldest architectural remnants in the castle are to be found in the cellar of this building and in the vaults under the large terrace in front of it, and may date to the Carolingian era. On the ground floor, in addition to reception and dining rooms, there is a rustic estate kitchen. Above this floor is a mezzanine level with appreciably lower ceilings, which formerly housed the actual living spaces for the owners. The upper floor above that contains three high-ceilinged formal rooms with remarkable sandstone chimneypieces.[14]

Castle mill

The castle mill was originally a freestanding building outside the castle defenses. It was integrated into the castle complex only in the course of later extensions that resulted from the division of the castle. The mill ground wheat for flour; the miller paid 5 malter of grain, 6 guilders and 8 albus in rent and for water usage. In addition, the lords of the castle were permitted to have their grains ground free at any time with no flour kept back by the miller.

Already by the early 20th century, electricity was being generated at the mill using the water; this was the origin of the later power plant. Around 1920, a large wood-fired stone oven, a so-called Königswinter oven, was installed, which provided the bread needed by the many people living and working at the castle. The oven has been restored and is again in use, providing baked goods for purchase and for consumption at the castle.[15]

Aerial view, lower castle in foreground

Aerial view, lower castle in foreground Courtyard of lower castle

Courtyard of lower castle View from the north

View from the north Carriage house

Carriage house- Tithe barn

Castle meadow

On the western side of the castle there is still a large meadow area, bordered in part by the Oosbach stream and in part by a millstream that branches off from it. The Oosbach originally fed the moats and later provided water to drive the mill and the electrical generator. In addition the water was used for the animals, to farm fish, and for firefighting. The millstream has largely been preserved and it has been possible to briefly reactivate it. The meadow area has been restored to showcase various biota and sculptures and provide locations for relaxation and nature observation. In 2004 it was featured in the Trier garden show.[10][16]

The lower castle grounds also include the historic approach to the castle (the Im Hofpesch path and the millrace path, both with old trees along them) and the upper stretch of the millstream and the sluice that diverts the water from the Oosbach.

Upper castle complex

The upper castle includes the following structures:

- The courtyard or bailey (bounded by buildings and a wall)

- Main building of the upper castle (an extended manorhouse in Renaissance and Baroque style)

- The so-called "Archive" (an extension that formerly belonged to the lower castle)

- Gate tower (14th-century, originally the only entrance to the castle)

- Barn (the southern side of the courtyard)

- Washhouse (eastern side of the courtyard)

- Administration building (Baroque)

- Park (originally the kitchen garden for both sections of the castle)

- Chapel house (a small building between the barn and the administration building that originally served as a chapel and burial place and was later converted into a residence)

- Gate house (an imposing Renaissance structure)

- Farmer's cottage (18th-century, between the upper castle gatehouse and the lower castle tithe barn), with living quarters, stable, barn, and a small courtyard.

Aerial photograph, upper castle in foreground

Aerial photograph, upper castle in foreground Towers of the upper castle, from the north

Towers of the upper castle, from the north Upper castle

Upper castle

References

- ↑ Magnus Backes (1960). Burgen und Stadtwehren der Eifel: ein Burgen- und Reiseführer. Burgenreihe. 3. Neuwied: Verlag Strüde. OCLC 614065935.

- ↑ Georg Dehio (1984). Handbuch der Deutschen Kunstdenkmäler Rheinland-Pfalz und Saarland. Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag. pp. 566–67. ISBN 3-422-00382-7.

- ↑ Paul Krämer (1962). Heimatbuch der Gemeinden Lissingen und Hinterhausen/Eifel. Lissingen: self-published. OCLC 256882723.

- ↑ Ernst Wackenroder (1983) [1927]. Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kreises Prüm. Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz. 12.2 (repr. ed.). Trier: Verlag der akademischen Buchhandlung Interbook. OCLC 74560938.

- ↑ "Lissingen, Kreis Daun". In: Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Heimatschutz (1910). Eifelburgen. Mitteilungen des Rheinischen Vereins für Denkmalpflege und Heimatschutz. 4.3. Düsseldorf: Schwann. OCLC 758448723.

- ↑ Paul Clemen (1983) [1928]. Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kreises Daun (repr. ed.). Düsseldorf: L. Schwann. pp. 694 ff. ISBN 3-88915-005-5.

- ↑ Franz Irsigler (1982). Herrschaftsgebiete im Jahre 1789: Beiheft zum Geschichtlichen Atlas der Rheinlande. Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Rheinische Geschichtskunde. Neue Folge 12.1b. Cologne: Rheinland-Verlag. ISBN 9783792706152.

- ↑ Erich Mertes-Kolverath (1993). "Die Einführung des Elektrizität in der Zentraleifel". Eifel-Jahrbuch. ISSN 0424-687X.

- ↑ Gerald Grommes (2000). "Burg Lissingen—Geschichte einer Wirtschaftsburg im 20. Jahrhundert". Heimatjahrbuch Kreis Daun. ISSN 0720-6976.

- 1 2 hfr (Hubertus Foerster) (2009). "Ein Haus der Geschichte: Burg Lissingen" (PDF). Hilla (in German). 2 (2): 16–17. (pdf)

- ↑ Michael Losse (2003). Hohe Eifel und Ahrtal: 57 Burgen und Schlösser. Theiss Burgenführer. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss. ISBN 9783806217759.

- ↑ Klaus Tombers; Else Tombers (1997). Klaus Tombers zeichnet ... an den Wassern zum Rhein. Cologne: Rheinland-Verlag. ISBN 9783792716250.

- ↑ Stella Junker-Mielke, ed. (2011). "Matt vor Seligkeit"—Sagenhafte Gärten der Region Mittelrhein. Ramsen: Verlag Cappi di Capua. ISBN 9783980015868.

- ↑ Bernhard Gondorf (1984). Die Burgen der Eifel und ihrer Randgebiete. Cologne: Bachem. ISBN 9783761607237.

- ↑ Erich Mertes (1994). Mühlen der Eifel: Geschichte - Technik - Untergang. Aachen: Helios Verlag. ISBN 9783925087547.

- ↑ Barbara Mikuda-Hüttel; Anita Burgard (2004). Gärten der Region: grüne Entdeckungen—zwischen Mosel & Saar und Sauer & Kyll. Trier: Weyand. ISBN 9783935281232.

Further reading

- Peter Bartlick. Geschichte der Burg Lissingen. Gerolstein, 2010.

- Eifelburgen. Mitteilungen des Rheinischen Vereins für Denkmalpflege und Heimatschutz 4.3 (December 1910). OCLC 758448723

- Karl F. Grommes. Kleiner Führer zur Geschichte der Burg Lissingen. Gerolstein 1999.

- Walter Hotz. Burgen am Rhein und an der Mosel. Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1958. OCLC 5472481

- Matthias Kordel. Die schönsten Schlösser und Burgen in der Eifel. Gudensberg-Gleichen: Wartberg, 1999. ISBN 9783861344827

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burg Lissingen. |

- Information about the lower castle

- Information about the upper castle

- "Lissingen". Alle Burgen (in German).