Lipka Tatars

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (10,000–15,000) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 7,300 (2009 census)[1] | |

| 2,800 (2011 census)[2] – 3,200[3] | |

| 1,916 (2011 census)[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Belarusian, Lithuanian, Polish | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Volga Tatars, Crimean Tatars | |

The Lipka Tatars (also known as Lithuanian Tatars, Polish Tatars, Lipkowie, Lipcani or Muślimi) are a group of Tatars who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century. The first settlers tried to preserve their shamanistic religion and sought asylum amongst the non-Christian Lithuanians.[5] Towards the end of the 14th century, another wave of Tatars – this time, Muslims, were invited into the Grand Duchy by Vytautas the Great. These Tatars first settled in Lithuania proper around Vilnius, Trakai, Hrodna and Kaunas [5] and later spread to other parts of the Grand Duchy that later became part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. These areas comprise present-day Lithuania, Belarus and Poland. From the very beginning of their settlement in Lithuania they were known as the Lipka Tatars. While maintaining their religion, they united their fate with that of the mainly Christian Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the Battle of Grunwald onwards the Lipka Tatar light cavalry regiments participated in every significant military campaign of Lithuania and Poland.

The Lipka Tatar origins can be traced back to the descendant states of the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan – the White Horde, the Golden Horde, the Crimean Khanate and Kazan Khanate. They initially served as a noble military caste but later they became urban-dwellers known for their crafts, horses and gardening skills. Throughout centuries they resisted assimilation and kept their traditional lifestyle. While they remained very attached to their religion, over time however, they lost their original Tatar language, from the Kipchak languages group of the Turkic languages, and for the most part adopted Belarusian, Lithuanian and Polish.[6] There are still small groups of Lipka Tatars living in today's Belarus, Lithuania and Poland, as well as their communities in United States.

Name

The name Lipka is derived from the old Crimean Tatar name of Lithuania. The record of the name Lipka in Oriental sources permits us to infer an original Libķa/Lipķa, from which the Polish derivative Lipka was formed, with possible contamination from contact with the Polish lipka "small lime-tree"; this etymology was suggested by the Tatar author S. Tuhan-Baranowski. A less frequent Polish form, Łubka, is corroborated in Łubka/Łupka, the Crimean Tatar name of the Lipkas up to the end of the 19th century. The Crimean Tatar term Lipka Tatarłar meaning Lithuanian Tatars, later started to be used by the Polish–Lithuanian Tatars to describe themselves.

In religion and culture the Lipka Tatars differed nominally from most other Islamic communities in respect of the treatment of their women, who always enjoyed a large degree of freedom, even during the years when the Lipkas were in the service of the Ottoman Empire. Co-education of male and female children was the norm, and Lipka women did not wear the veil – except at the marriage ceremony. While traditionally Islamic, the customs and religious practices of the Lipka Tatars also accommodated many Christian elements adopted during their 600 years residence in Belarus, Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania while still maintaining the traditions and superstitions from their nomadic Mongol past, such as the sacrifice of bulls in their mosques during the main religious festivals.

Over time, the lower and middle Lipka Tatar nobles adopted the Ruthenian language then later the Belarusian language as their native language.[6][7] However, they used the Arabic alphabet to write in Belarusian until the 1930s. The upper nobility of Lipka Tatars spoke Polish.

Diplomatic correspondence between the Crimean Khanate and Poland from the early 16th century refers to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as the "land of the Poles and the Lipkas".[7] By the 17th century the term Lipka Tatar began to appear in the official documents of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

History

The migration of some Tartars into the lands of Lithuania and Poland from Golden Horde began during the 14th century and lasted until the end of the 17th. There was a subsequent wave of Tatar immigrants from Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, although these consisted mostly of political and national activists.[7]

According to some estimates, by 1590–1591 there were about 200,000 [8] Lipka Tatars living in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and about 400 mosques serving them. According to the Risāle-yi Tatar-i Leh (trans: Message Concerning the Tatars of Poland, an account of the Lipka Tatars written for Süleyman the Magnificent by an anonymous Polish Muslim during a stay in Constantinople in 1557–1558 on his way to Mecca) there were 100 Lipka Tatar settlements with mosques in Poland. The largest communities existed in the cities of Lida, Navahradak and Iwye. There was a Lipka Tatar settlement in Minsk, today's capital of Belarus, known as Tatarskaya Slabada.

In the year 1672, the Tatar subjects rose up in open rebellion against the Commonwealth. This was the widely remembered Lipka Rebellion. Thanks to the efforts of King Jan III Sobieski, who was held in great esteem by the Tatar soldiers, many of the Lipkas seeking asylum and service in the Turkish army returned to his command and participated in the struggles with the Ottoman Empire up to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, including the Battle of Vienna (1683) that was to turn the tide of Islamic expansion into Europe and mark the beginning of the end for the Ottoman Empire.

Beginning in the late 18th and throughout the 19th century the Lipkas became successively more and more Polonized. The upper and middle classes in particular adopted Polish language and customs (although they nominally kept Islam as their religion), while the lower ranks became Ruthenized. At the same time, the Tatars held the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas (Wattad in Tatar, or "defender of Muslims in non Muslim lands"), who encouraged and supported their settlement during the 15th century, in great esteem, including him in many legends, prayers and their folklore.[7] Throughout the 20th and since the 21st centuries, most Tatars no longer view religious identity as being as important as it once was, and the religious and linguistic subgroups have intermingled considerably; for example, the Tatar women in Poland do not practice and view vieling (wearing headscarf/hijab) as a mandatory religious obligation,[9][10] but rather an influence of an Arabic culture on an Islamic customs. Many Polish Tatars, especially and mainly the youth, also drink alcohol.

Timeline

- 1226: The Khanate of the White Horde was established as one of the successor states to the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan. The first Khan, Orda was the second son of Jochi, the eldest son of Genghis Khan. The White Horde occupied the southern Siberian steppe from the east of the Urals and the Caspian Sea to Mongolia.

- 1380: Khan Tokhtamysh, the hereditary ruler of the White Horde, crossed west over the Urals and merged the White Horde with the Golden Horde whose first khan was Batu, the eldest son of Jochi. In 1382 the White and Golden Hordes sacked and burned Moscow. Tokhtamysh, allied with the great central Asian Tatar conqueror Tamerlane, reasserted Mongol power in Russia.

- 1397: After a series of disastrous military campaigns against his former protector, the great Tatar warlord Tamerlane, Tokhtamysh and the remnants of his clan were granted asylum and given estates and noble status in Grand Duchy of Lithuania by Vytautas the Great. The settlement of the Lipka Tatars in Lithuania in 1397 is recorded in the Chronicles of Jan Długosz.

- 1397: The Italian city state of Genoa funded a joint expedition by the forces of Khan Tokhtamysz and Grand Duke Vytautas against Tamerlane. This campaign was notable for the fact that the Lipka Tatars and Lithuanian armies were armed with handguns, but no major victories were achieved.

- 15 July 1410: The Battle of Grunwald took place between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on one side (c. 39,000 troops), and the Teutonic Knights on the other (c. 27,000 troops). The Teutonic knights were defeated and never recovered their former influence. After the battle, rumours spread across Europe that the Germans had only been defeated thanks to the aid of tens of thousands of heathen Tatars, though it is likely there were no more than 1,000 Tatar horse archers at the battle, the core being the entourage of Jalal ad-Din, son of Khan Tokhtamysh. At the start of the battle, Jalal ad-Din led the Lipka Tatar and Lithuanian light cavalry on a suicide charge against the Teutonic Knights' artillery positions – the original "Charge of the Light Brigade". The Teutonic Knights' Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen responded by ordering his own heavy cavalry to pursue the Lipkas away from the field of battle, trampling through their own infantry in the process. The resulting destruction of the Teutonic Knights' line of battle was a major factor in their subsequent defeat. This incident forms one of the highlights of Aleksander Ford's 1960 film Krzyżacy (Knights of the Teutonic Order), based on the historical novel of the same name by Nobel laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz.

- 1528: The Polish (szlachta) and Lithuanian nobility's legal right to retribution on the grounds of the wounding or killing of a nobleman or a member of his family is extended to the Lipka Tatars.

- 1569: Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth is founded at the Union of Lublin. Companies of Lipka Tatar light cavalry for a long time constituted one of the foundations of the military power of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Lithuanian Tatars, from the very beginning of their residence in Lithuania were known as the Lipkas. They united their fate with that of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the Battle of Grunwald onwards they participated in every significant military campaign.

- 1591: The rule of the fervent Catholic Sigismund III (1587–1632) and the Counter-Reformation movement brought a number of restrictions to the liberties granted to non-Catholics in Poland, the Lipkas amongst others. This led to a diplomatic intervention by Sultan Murad III with the Polish king in 1591 on the question of freedom of religious observance for the Lipkas. This was undertaken at the request of Polish Muslims who had accompanied the Polish King's envoy to Istanbul.

- 1672: The Lipka Rebellion. As a reaction to restrictions on their religious freedoms and the erosion of their ancient rights and privileges, the Lipka Tatar regiments stationed in the Podolia region of south-east Poland abandoned the Commonwealth at the start of the late 17th century Polish–Ottoman Wars that were to last to end of the 17th century with the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The Lipka Rebellion forms the background to the novel Pan Wolodyjowski, the final volume of the historical Trylogia of Henryk Sienkiewicz, the Nobel Prize winning author (1905) who was himself descended from Christianised Lipka Tatars. The 1969 film of Pan Wolodyjowski, directed by Jerzy Hoffman and starring Daniel Olbrychski as Azja Tuhaj-bejowicz, still remains among the biggest box-office success in the history of Polish cinema.

- 1674: After the famous Polish victory at Chocim, the Lipka Tatars who held the Podolia for Turkey from the stronghold of Bar were besieged by the armies of Jan Sobieski, and a deal was struck that the Lipkas would return to the Polish side subject to their ancient rights and privileges being restored.

- 1676: The Treaty of Zurawno that brought a temporary end to the Polish–Ottoman wars stipulated that the Lipka Tatars were to be given a free individual choice of whether they wanted to serve the Ottoman Empire or the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- 1677: The Sejm in March 1677 confirmed all the ancient Tatar rights and privileges. The Lipka Tatars were permitted to rebuild all their old mosques, to settle Christian labour on their estates and to buy up noble estates that had not previously belonged to Tatars. The Lipka Tatars were also freed from all taxation.

- 1679: As a reward for their return to the Commonwealth the Lipka Tatars were settled by King Jan Sobieski on Crown Estates in the provinces of Brest, Kobryn and Hrodna. The Tatars received land that had been cleared of the previous occupants, from 0.5 to 7.5 square kilometres per head, according to rank and length of service.

- 1683: Many of the Lipka Tatar rebels who returned to the service of the Commonwealth in 1674 were later to take part in the Vienna Campaign of 1683. This included the 60 Polish Tatars in the light cavalry company of Samuel Mirza Krzeczowski, who was later to save the life of King Jan III Sobieski during the disastrous first day of the Battle of Parkany, a few weeks after the great victory of the Battle of Vienna that was to turn the tide of Islamic expansion into Europe and mark the beginning of the end for the Ottoman Empire. The Lipka Tatars who fought on the Polish side at the Battle of Vienna, on 12 September 1683, wore a sprig of straw in their helmets to distinguish themselves from the Tatars fighting under Kara Mustafa on the Turkish side. Lipkas visiting Vienna traditionally wear straw hats to commemorate their ancestors’ participation in the breaking of the Siege of Vienna.

- 1699: Some of the Kamieniec-based Lipka Tatars who had remained loyal to the Turkish Sultan were settled in Bessarabia along the borderlands between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as well as in the environs of Chocim and Kamieniec-Podolski and in the town known as Lipkany. A further large scale emigration of Lipkas to Ottoman controlled lands took place early in the 18th century, after the victory won by King Augustus II over the Polish-born King Stanisław Leszczyński, whom the Lipkas had supported in his war against the Saxon King.

Lipka Tatar family

Lipka Tatar family - 1775: The Polish Lipkas came back into favour during the reign of the last King, Stanislas Augustus (1765–95). In 1775 the Sejm reaffirmed the noble status of the Polish Lithuanian Tatars. After the Partitions of Poland, the Lipkas played their part in the various national uprisings, and also served alongside the Poles in the Napoleonic army.

- 1919: The Polish Lipkas joined the newly created Polish Army formations; Pułk Jazdy Tatarskiej and later, 13th Regiment of Wilno Uhlans.

- 1939: With the re-emergence of the Polish state after the First World War, a Polish Tatar regiment was re-established in the Polish Army which was distinguished by its own uniforms and banners. After the fall of Poland in 1939, the Polish Tatars in the Wilno (Vilnius) based 13th Cavalry Regiment were one of the last Polish Army units recorded carrying on the fight against the German aggressors while led by Major Aleksander Jeljaszewicz.[11]

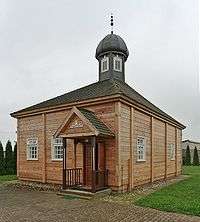

Muslim Lipka Tatar cemetery in Bohoniki, Poland gallery

Entrance

Entrance

Ruthenian language Arabic script on a tombstone

Ruthenian language Arabic script on a tombstone Damaged tombstone

Damaged tombstone

Present status

.jpg)

Today there are about 10,000–15,000 Lipka Tatars in the former areas of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The majority of descendants of Tatar families in Poland can trace their descent from the nobles of the early Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Lipka Tatars had settlements in north-east Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, south-east Latvia and Ukraine. Today most reside in Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus. Most of the Lipka Tatars (80%) assimilated into the ranks of the nobility in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth while some lower noble Tatars assimilated to the Belarusian, Polish, Ukrainian and Lithuanian townsfolk and peasant populations.

A number of the Polish Tatars emigrated to the US at the beginning of the 20th century and settled mostly in the north eastern states, although there is also an enclave in Florida. A small but active community of Lipka Tatars exists in New York City. "The Islamic Center of Polish Tatars" was built in 1928 in Brooklyn, New York City, and functioned until recently.[6]

After the annexation of eastern Poland into the Soviet Union following World War II, Poland was left with only 2 Tatar villages, Bohoniki and Kruszyniany. A significant number of the Tatars in the territories annexed to the USSR repatriated to Poland and clustered in cities such as Gdańsk, Białystok, Warsaw and Gorzów Wielkopolski totaling some 3,000 people. One of the neighborhoods of Gorzów Wielkopolski where relocated Tatar families resettled has come to be referred to as "the Tatar Hills", or in Polish "Górki Tatarskie".

In 1925 the Muslim Religion Association (Polish: Muzułmański Związek Religijny) was formed in Białystok, Poland. In 1992, the Organization of Tatars of the Polish Republic (Polish: Związek Tatarów Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej) with autonomous branches in Białystok and Gdańsk, began operating.

In Poland, the 2011 census showed 1,916 people declaring Tatar ethnicity.[4]

In November 2010, a monument to Poland's Tatar populace was unveiled in the port city of Gdańsk at a ceremony attended by President Bronislaw Komorowski, as well as Tatar representatives from across Poland and abroad. The monument is a symbol of the important role of Tatars in Polish history. "Tatars shed their blood in all national independence uprisings. Their blood seeped into the foundations of the reborn Polish Republic," President Komorowski said at the unveiling. The monument is the first of its kind to be erected in Europe.

Famous Lipka Tatar descendants

- Gasan (Hasan) Konopackiy – Russian, Belarusian and Polish military and political leader

- Aleksander Jeljaszewicz – Major of the Polish Army; commander of the last Tatar/Islamic unit in the Polish military

- Ibragim Kanapatsky – Belarusian socio-political, cultural and religious figure, historian

- Tomasz Miśkiewicz – Polish mufti

- Aleksander Romanowicz – General of cavalry in Russian Imperial Army and Polish Army

- Aleksander Sulkiewicz – Polish politician of, activist in socialist and independence movements and one of the co-founders of Polish Socialist Party

- Charles Bronson – Lithuanian-American actor (father Lipka Tatar)

- Fatma Mukhtarova – Soviet opera singer (mother Lipka Tatar)

- Henryk Sienkiewicz – Polish Nobel Prize-winning novelist (paternally of distant Lipka Tatar ancestry)

- Maciej Sulkiewicz – lieutenant general of the Russian Imperial Army, Prime Minister of the Crimean Regional Government, and Chief of General Staff of Azerbaijani Armed Forces in 1918–1920

- Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky – Ukrainian statesman, economical scientist of the Russian Empire (paternally of partial Lipka Tatar ancestry)

- Osman Achmatowicz – chemist

- Mustafa Edige Kirimal – Crimean politician (paternally of partial Lipka Tatar ancestry)

- Jakub Szynkiewicz – Polish mufti

Two distantly related members of the Abakanowicz family

- Bruno Abakanowicz – mathematician, inventor and electrical engineer (distant paternal Lipka Tatar ancestry)[12]

- Magdalena Abakanowicz – Polish artist whose family is of distant Tatar origin (distant paternal Lipka Tatar ancestry)

See also

- Lipka Rebellion

- Tatar invasions

- List of Polish wars

- Aleksander Sulkiewicz

- Kaliz

- Almış (Almas) iltäbär

- Aleksander Jeljaszewicz

- Belarusian Arabic alphabet

- Lithuanian Tartars of the Imperial Guard

- Islam in Poland

References

- ↑ "Перепись-2009". Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ "M3010215: Population at the beginning of the year by ethnicity". Data of 2011 Population Census. Lietuvos statistikos departamentas. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ "Eastern Europe and migrants: The mosques of Lithuania". The Economist. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna - NSP 2011" (PDF) (in Polish).

- 1 2 (in Lithuanian) Lietuvos totoriai ir jų šventoji knyga - Koranas Archived 29 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, "Polish or Lithuanian Tartars", Harvard University Press, pg. 990

- 1 2 3 4 Selim Mirza-Juszeński Chazbijewicz, "Szlachta tatarska w Rzeczypospolitej" (Tartar Nobility in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth), Verbum Nobile no 2 (1993), Sopot, Poland, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 January 2006. Retrieved 2006-02-23.

- ↑ Olson, James (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. p. 450. ISBN 0-313-27497-5.

- ↑ Tarlo, Emma; Moors, Annelies (15 August 2013). "Islamic Fashion and Anti-Fashion: New Perspectives from Europe and North America". A&C Black. Retrieved 31 May 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ http://islamicreligiouseducation.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/islamische_rel/ip-costance/Polish_Tatar_Women_ANalborczyk.pdf

- ↑ Jan Tyszkiewicz. Z dziejów Tatarów polskich: 1794–1944, Pułtusk 2002, ISBN 83-88067-81-8

- ↑ Por. S. Dziadulewicz, Herbarz rodzin tatarskich, Wilno 1929, s. 365.

External links

- A Short History of the Lipka Tatars of the White Horde Jakub Mirza Lipka

- Tartar Nobility in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Selim Mirza-Juszenski Chazbijewicz - translated into English by Paul de Nowina-Konopka

- The Lithuanian Tatars article in The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire