Linear particle accelerator

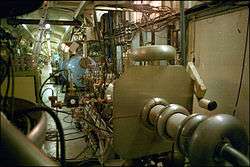

A linear particle accelerator (often shortened to linac) is a type of particle accelerator that greatly increases the kinetic energy of charged subatomic particles or ions by subjecting the charged particles to a series of oscillating electric potentials along a linear beamline. The principles for such machines were proposed by Gustav Ising in 1924,[1] while the first machine that worked was constructed by Rolf Widerøe in 1928 [2] at the RWTH Aachen University. Linacs have many applications: they generate X-rays and high energy electrons for medicinal purposes in radiation therapy, serve as particle injectors for higher-energy accelerators, and are used directly to achieve the highest kinetic energy for light particles (electrons and positrons) for particle physics.

The design of a linac depends on the type of particle that is being accelerated: electrons, protons or ions. Linacs range in size from a cathode ray tube (which is a type of linac) to the 3.2-kilometre-long (2.0 mi) linac at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California.

Construction and operation

A linear particle accelerator consists of the following elements:

- The particle source. The design of the source depends on the particle that is being moved. Electrons are generated by a cold cathode, a hot cathode, a photocathode, or radio frequency (RF) ion sources. Protons are generated in an ion source, which can have many different designs. If heavier particles are to be accelerated, (e.g., uranium ions), a specialized ion source is needed.

- A high voltage source for the initial injection of particles.

- A hollow pipe vacuum chamber. The length will vary with the application. If the device is used for the production of X-rays for inspection or therapy the pipe may be only 0.5 to 1.5 meters long. If the device is to be an injector for a synchrotron it may be about ten meters long. If the device is used as the primary accelerator for nuclear particle investigations, it may be several thousand meters long.

- Within the chamber, electrically isolated cylindrical electrodes are placed, whose length varies with the distance along the pipe. The length of each electrode is determined by the frequency and power of the driving power source and the nature of the particle to be accelerated, with shorter segments near the source and longer segments near the target. The mass of the particle has a large effect on the length of the cylindrical electrodes; for example an electron is considerably lighter than a proton and so will generally require a much smaller section of cylindrical electrodes as it accelerates very quickly. Likewise, because its mass is so small, electrons have much less kinetic energy than protons at the same speed. Because of the possibility of electron emissions from highly charged surfaces, the voltages used in the accelerator have an upper limit, so this can't be as simple as just increasing voltage to match increased mass.

- One or more sources of radio frequency energy, used to energize the cylindrical electrodes. A very high power accelerator will use one source for each electrode. The sources must operate at precise power, frequency and phase appropriate to the particle type to be accelerated to obtain maximum device power.

- An appropriate target. If electrons are accelerated to produce X-rays then a water cooled tungsten target is used. Various target materials are used when protons or other nuclei are accelerated, depending upon the specific investigation. For particle-to-particle collision investigations the beam may be directed to a pair of storage rings, with the particles kept within the ring by magnetic fields. The beams may then be extracted from the storage rings to create head on particle collisions.

As the particle bunch passes through the tube it is unaffected (the tube acts as a Faraday cage), while the frequency of the driving signal and the spacing of the gaps between electrodes are designed so that the maximum voltage differential appears as the particle crosses the gap. This accelerates the particle, imparting energy to it in the form of increased velocity. At speeds near the speed of light, the incremental velocity increase will be small, with the energy appearing as an increase in the mass of the particles. In portions of the accelerator where this occurs, the tubular electrode lengths will be almost constant.

- Additional magnetic or electrostatic lens elements may be included to ensure that the beam remains in the center of the pipe and its electrodes.

- Very long accelerators may maintain a precise alignment of their components through the use of servo systems guided by a laser beam.

Advantages

Linacs of appropriate design are capable of accelerating heavy ions to energies exceeding those available in ring-type accelerators, which are limited by the strength of the magnetic fields required to maintain the ions on a curved path. High power linacs are also being developed for production of electrons at relativistic speeds, required since fast electrons traveling in an arc will lose energy through synchrotron radiation; this limits the maximum power that can be imparted to electrons in a synchrotron of given size. Linacs are also capable of prodigious output, producing a nearly continuous stream of particles, whereas a synchrotron will only periodically raise the particles to sufficient energy to merit a "shot" at the target. (The burst can be held or stored in the ring at energy to give the experimental electronics time to work, but the average output current is still limited.) The high density of the output makes the linac particularly attractive for use in loading storage ring facilities with particles in preparation for particle to particle collisions. The high mass output also makes the device practical for the production of antimatter particles, which are generally difficult to obtain, being only a small fraction of a target's collision products. These may then be stored and further used to study matter-antimatter annihilation.

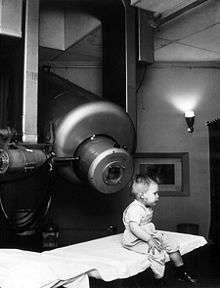

Medical linacs

Linac-based radiation therapy for cancer therapy began with treatment of the first patient in 1953 in London at Hammersmith Hospital, with an 8 MV machine built by Metropolitan-Vickers, as the first dedicated medical linac.[3] A short while later in 1955, 6 MV linac therapy from a different machine was being used in the United States.

Medical grade linacs accelerate electrons using a tuned-cavity waveguide, in which the RF power creates a standing wave. Some linacs have short, vertically mounted waveguides, while higher energy machines tend to have a horizontal, longer waveguide and a bending magnet to turn the beam vertically towards the patient. Medical linacs use monoenergetic electron beams between 4 and 25 MeV, giving an X-ray output with a spectrum of energies up to and including the electron energy when the electrons are directed at a high-density (such as tungsten) target. The electrons or X-rays can be used to treat both benign and malignant disease. The LINAC produces a reliable, flexible and accurate radiation beam. The versatility of LINAC is a potential advantage over cobalt therapy as a treatment tool. In addition, the device can simply be powered off when not in use; there is no source requiring heavy shielding – although the treatment room itself requires considerable shielding of the walls, doors, ceiling etc. to prevent escape of scattered radiation. Prolonged use of high powered (>18 MeV) machines can induce a significant amount of radiation within the metal parts of the head of the machine after power to the machine has been removed (i.e. they become an active source and the necessary precautions must be observed).

Application for medical isotope development

The expected shortages with regard to Mo-99, and the technetium-99m medical isotope obtained from it, has also shed light onto linear accelerator technology to produce Mo-99 from non-enriched Uranium-235 through neutron bombardment. This would enable the medical isotope industry to manufacture this crucial isotope by a sub-critical process. The aging facilities, for example the Chalk River Laboratories in Ontario Canada, which still now produce most Mo-99 from highly enriched Uranium-235 could be replaced by this new process. In this way, the sub-critical loading of soluble uranium salts in heavy water with subsequent photo neutron bombardment and extraction of the target product, Mo-99, will be achieved.[4]

Disadvantages

- The device length limits the locations where one may be placed.

- A great number of driver devices and their associated power supplies are required, increasing the construction and maintenance expense of this portion.

- If the walls of the accelerating cavities are made of normally conducting material and the accelerating fields are large, the wall resistivity converts electric energy into heat quickly. On the other hand, superconductors also need constant cooling to keep them below their critical temperature, and the accelerating fields are limited by quenches. Therefore, high energy accelerators such as SLAC, still the longest in the world (in its various generations), are run in short pulses, limiting the average current output and forcing the experimental detectors to handle data coming in short bursts.

See also

- Accelerator physics

- Beamline

- CERN

- Compact Linear Collider

- Dielectric wall accelerator

- Duoplasmatron

- Electromagnetism

- International Linear Collider

- KEK

- Los Alamos Neutron Science Center

- List of particles

- Particle accelerator

- Particle beam

- Particle physics

- Quadrupole magnet

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

- Soreq Applied Research Accelerator Facility

- Superconducting radio frequency

References

- ↑ G. Ising: Prinzip einer Methode zur Herstellung von Kanalstrahlen hoher Voltzahl. In: Arkiv för Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik. Band 18, Nr. 30, 1924, S. 1–4.

- ↑ Widerøe, R. (17 December 1928). "Über Ein Neues Prinzip Zur Herstellung Hoher Spannungen". Archiv für Elektronik und Übertragungstechnik. 21 (4): 387. doi:10.1007/BF01656341.

- ↑ LINAC-3, Advances in Medical Linear Accelerator Technology. ampi-nc.org

- ↑ Gahl and Flagg (2009).Solution Target Radioisotope Generator Technical Review. Subcritical Fission Mo99 Production. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

External links

- Linear Particle Accelerator (LINAC) Animation by Ionactive

- 2MV Tandetron linear particle accelerator in Ljubljana, Slovenia