Lilias Armstrong

| Lilias Eveline Armstrong | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Armstrong, unknown date.[1] | |

| Born |

29 September 1882 Pendlebury, City of Salford, U.K. |

| Died |

9 December 1937 (aged 55) North Finchley, London, U.K. |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | Lilias Eveline Boyanus |

| Education | B.A., University of Leeds, 1906 |

| Occupation | Phonetician |

| Employer | Phonetics Department, University College, London |

| Works | See Lilias Armstrong bibliography |

| Spouse(s) | Simon Charles Boyanus (m. 1926; her death 1937) |

Lilias Eveline Armstrong (29 September 1882 – 9 December 1937) was an English phonetician who was a reader at University College London. She is most known for her work on English intonation as well as the phonetics and tone of Somali and Kikuyu.

She grew up in Northern England, graduated from the University of Leeds, and was initially an elementary school French teacher in the London suburbs. However she eventually realized her passion was phonetics and joined the University College Phonetics Department, headed by Daniel Jones. Her most notable works were the 1926 book A Handbook of English Intonation, co-written with Ida C. Ward, the 1934 paper "The Phonetic Structure of Somali", and the book The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu, published posthumously in 1940 after she died of a stroke in 1937 at age 55.

She was the subeditor of the International Phonetic Association's journal Le Maître Phonétique for more than a decade, and was praised in her day for her teaching, both during the academic term and in the department's summer vacation courses. Jones wrote in his obituary of her that she was "one of the finest phoneticians in the world."[2]

Early life

Lilias Eveline Armstrong was born 29 September 1882 in Pendlebury, City of Salford, in Greater Manchester to James William Armstrong, a Free Methodist minister, and Mary Elizabeth Armstrong, née Hunter.[3] She went to infant school in Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, but by 1889, she and her family were living in Louth, Lincolnshire and Lilias and four of her siblings had registered to attend Newmarket Council School.[4] Her upbringing led to her speech having certain Northern English characteristics.[5]

Armstrong studied French and Latin at the University of Leeds,[6][7] where she was a king's scholar.[6] She received her B.A. in 1906,[8] and she was also trained as a teacher.[9] She attended the University of Leeds Day Training College and got a Board of Education Certificate.[10]

After graduating from Leeds, she was a French teacher in East Ham, Greater London for several years; she had success in this line of work, and was well on her way to becoming headmistress by the time she left this position in 1918.[11] While she was Senior Assistant Mistress, she began studying phonetics in the evenings part-time at the University College Phonetics Department in order to improve her teaching of French pronunciation.[11] In 1917, Armstrong received a Diploma with Distinction in French Phonetics and she got a Diploma with Distinction in English phonetics in 1918.[12]

Academic career

Teaching and lecturing

Employment history

.jpg)

Armstrong's first experience teaching phonetics was in summer 1917, in Daniel Jones's summer course for missionaries to learn phonetics; even before then, however, Jones had planned to give Armstrong a full-time position at the University College Phonetics Department.[14] Those plans were temporarily put on hold when London County Council decided against a budgetary increase for the department in October, but in November 1917, Jones nominated Armstrong to receive a temporary, part-time lectureship, which she started in February 1918.[15] She was finally able to work full-time at the start of the 1918–1919 academic year,[16] becoming the Phonetics Department's first full-time assistant.[17] She became lecturer in 1920,[18] senior lecturer in 1921,[19] and reader in 1937.[20] Her promotion to readership was announced in The Times[21] and The Universities Review.[22] Armstrong also occasionally taught at the School of Oriental Studies.[23] When Jones had to take a leave of absence the first nine months of 1920, Armstrong became acting head of the department in his stead.[24] During this time, she interviewed and admitted students into the department.[25] Other positions she held at University College were Chairman of the Refectory Committee and Secretary of the Women Staff Common Room.[26] Learned societies Armstrong belonged to included the International Phonetic Association,[27] the Modern Language Association,[28] and the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences.[29]

Courses and lectures

In addition to teaching courses on French and English phonetics,[30] Armstrong taught courses on the phonetics of Swedish[31] and of Russian.[32] She also taught a class on speech pathology alongside Daniel Jones titled "Lecture-demonstrations on Methods of Correcting Defects of Speech".[33] Armstrong also led ear-training exercises,[34] which were an important part of teaching at the University College Department of Phonetics.[35]

Armstrong was also involved in the teaching of several vacation courses held at University College. In 1919, the Phonetics Department began teaching its popular vacation courses in French and English phonetics.[36] In the inaugural 1919 course, Armstrong conducted daily ear-training exercises for a course geared for those studying and teaching French.[37] Two readers of English Studies who had attended the 1919 summer course for English favourably described Armstrong's ear-tests as "a great help" and "splendid";[38] these ear-training exercises were also praised by the journal Leuvensche Bijdragen.[39] A Dutch participant in the 1921 session also highly praised Armstrong's ear-training classes and provided a description thereof.[40] By the 1921 summer course, she not only conducted the ear-training exercises, but also lectured on English phonetics alongside Jones;[39][41] she also gave lectures on English phonetics for a "Course of Spoken English for Foreigners", taught with Jones and Arthur Lloyd James during the summer of 1930.[42] An advertisement for the 1935 summer course described the whole program as being "under the general direction" of Jones and Armstrong; that year included lectures taught by Armstrong and Firth as well as ear-training exercises led by Jones and Armstrong.[43]

In October 1922, she delivered a public lecture at University College about the use of phonetics in teaching French.[44] Armstrong also delivered a speech to the Verse Speaking Fellowship's annual conference in 1933.[45] She travelled to Sweden in 1925 to deliver lectures on English intonation, going to Gothenburg in September and Stockholm in October.[46] She also gave a lecture on English intonation to a meeting of the Modern Language Society of Helsinki, Finland, in April 1927.[47] Other countries Armstrong travelled to in order to give lectures include the Netherlands and the Soviet Union.[48]

Students

Lilias Armstrong had several students who were well-known scholars and linguists themselves. Suniti Kumar Chatterji studied at the University of London from 1919 to 1921 for his D.Litt.; while he was there, Lilias Armstrong and Ida C. Ward taught him phonetics and drilled him with ear-training and transcription exercises.[49] John Rupert Firth, who would later work at the University College Phonetics Department himself along Armstrong, was a student at University College from 1923 to 1924; the classes he took included Armstrong's course in French Phonetics.[50] In the summer of 1934, Ian Catford, then age 17, took a class in French phonetics taught by Armstrong and Hélène Coustenoble.[51] Armstrong taught advanced phonetics to Lorenzo Dow Turner while he was doing postdoctoral research at SOAS from 1936 to 1937.[52][53] Jean-Paul Vinay, who got his masters degree studying under Armstrong in 1937 and later worked alongside her, specifically pointed out Armstrong's kindness and articulatory prowess.[54] While Robert Guy Howarth was studying for his doctorate in English from 1937 to 1938, he also got a certificate in phonetics and took "A Course of General Phonetics", taught by Armstrong and others.[55]

Writing and research

Le Maître Phonétique

The International Phonetic Association had suspended publication of its journal Le Maître Phonétique during World War I, but in 1921 it began producing a yearly publication Textes pour nos élèves ("Texts for our students"), which consisted of texts transcribed in IPA from various languages,[58] such as English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish.[59] Lilias Armstrong contributed several transcriptions of English texts throughout its volumes.[60]

In 1923, Le Maître Phonétique resumed publication and started its third series. Lilias Armstrong was listed as the secrétaire de rédaction (subeditor) starting from the July–September 1923 issue (3rd Ser. 3), and she held this position throughout the January–March 1936 issue (3rd Ser. 53).[61] She had a significant role in the renewal of the journal and of the International Phonetic Association,[62] whose activities depended on the journal's publication.[58] She wrote various book reviews in the journal's kɔ̃trɑ̃dy[lower-alpha 2] (Comptes rendus, "Reports") section,[65] as well as phonetic transcriptions of English texts in its parti dez elɛːv (Partie des élèves, "Students' section").

Le Maître Phonétique's spesimɛn (Spécimens, "Specimens") section consisted of short phonetic sketches of less-studied languages and a phonetic transcription of a short text. For instance, one year Le Maître Phonétique had specimens of Gã, Biscayan, Japanese English, Poitevin, and Punjabi.[66] Armstrong's first specimen was of Swedish and published in 1927; it consisted of an inventory of Swedish vowels and a transcription of "ˊmanˑən sɔm ˇtapˑadə ˇykˑsan"[lower-alpha 3] (Mannen som tappade yxan, "The man who dropped his axe"), a translation of "The Honest Woodcutter", as pronounced by Fröken Gyllander of Stockholm.[70] Earlier, Immanuel Björkhagen had thanked Armstrong for her assistance in describing the phonetics and sound-system of Swedish in his 1923 book Modern Swedish Grammar.[71] Armstrong's second specimen, published in 1929, was of Russian and consists of a transcription of an excerpt of Nikolai Gogol's "May Night, or the Drowned Maiden."[72] Armstrong had also corrected the proof of M. V. Trofimov and Daniel Jones's 1923 book The Pronunciation of Russian.[73] Armstrong also did research on Arabic phonetics, but never published anything on the subject;[74] she did, however, write a review of William Henry Temple Gairdner's book on Arabic phonetics for Le Maître Phonétique.[75]

London Phonetic Readers Series

Armstrong's first two books, An English Phonetic Reader (1923)[76] and A Burmese Phonetic Reader (1925, with Pe Maung Tin),[77] were part of the London Phonetics Readers Series, edited by Daniel Jones. Books in this series provided a phonetic sketch as well as texts transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet.[78] Jones had encouraged Armstrong to write a phonetic reader of English in "narrow transcription".[79] One of the chief distinctions of "narrow transcription" for English was the use of the additional phonetic symbols for vowels, such as [ɪ] (as in the RP pronunciation of kit), [ʊ] (foot), and [ɒ] (lot).[80] In the analysis behind a Jonesian "broad transcription" of English, the principal difference between those vowels and the vowels [iː] (fleece), [uː] (goose), and [ɔː] (thought), respectively, was thought of as length instead of quality;[81] accordingly, the absence or presence of a length diacritic was used to distinguish these vowels instead of using different symbols.[82] Armstrong's narrow transcription for the reader used these extra vowel symbols and explicitly marked vowel length with the diacritics ˑ 'half-long' and ː 'long'.[83] She also discussed the use of narrow transcription in her first paper for Le Maître Phonetique, in which she implored the journal's readers to learn to use the extra symbols.[84] Armstrong's An English Phonetic Reader, Armstrong and Ward's Handbook of English Intonation, and Ward's The Phonetics of English were the first to popularize this transcription system for English.[85] Armstrong's English phonetic reader included transcriptions of passages written by Alfred George Gardiner, Henry James, Robert Louis Stevenson, Thomas Hardy, and John Ruskin.[86]

- myauʔ ˍle ˋmiŋ nɛ ˍne ˋmiŋ (Firth)

- mjaʊʔlemɪ̃́nɛ̰ neːmɪ̃́ (Watkins).[87]

Armstrong's second book for the series was a Burmese reader, co-written with Pe Maung Tin. Pe Maung Tin had the opportunity to study phonetics at University College and collaborate with Armstrong while he was in London studying law at Inner Temple and attending lectures by Charles Otto Blagden about Old Mon inscriptions.[88] Prior to the publication of the Burmese reader, Pe Maung Tin had written a Burmese specimen for Le Maître Phonétique.[89] William Cornyn described their reader as having an "elaborate description" of Burmese phonetics.[90] Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin developed the first transcription of in accordance to principles of the International Phonetic Association; this was a "very detailed" transcription scheme, which made use of five diacritics for tone, some of which could be placed at multiple heights.[91] The number of specialized phonetic symbols and diacritics was a complaint of one contemporary review of this book.[92] Pe Maung Tin responded to this review by clarifying the diacritics were necessary to convey the interaction of tone and prosody and to ensure that English speakers did not read the texts with an English intonation.[93] He also defended other transcription choices like using "sh" to represent an aspirated alveolar fricative as in the Burmese word ဆီ (IPA: [sʰì], "oil"), which Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin transcribed as "ˍshiː";[94] the reviewer thought it was confusing to use "sh" to refer to a sound other than the post-alveolar fricative represented by the English ⟨sh⟩ as in the word she (IPA: /ʃiː/).[95] R. Grant Brown, a former member of the Indian Civil Service in Burma, praised A Burmese Phonetic Reader for being the joint work of a phonetician and a native speaker, writing "This excellent little book sets a standard which other writers on living Oriental languages will have to follow if they do not wish their work to be regarded as second-rate",[96] although he thought their transcription system was "too elaborate for ordinary use."[97] John Rupert Firth used a broad transcription which he simplified from Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin's system based in part on his experience using their Reader with Burmese speakers and with students of Burmese phonetics at Oxford's Indian Institute.[98] Minn Latt said their transcription system used too many "unfamiliar symbols" for an ideal romanization scheme.[99] Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin's translation of "The North Wind and the Sun" was used in Justin Watkins's 2001 illustration of the IPA for Burmese in the Journal of the International Phonetic Association.[100]

English intonation

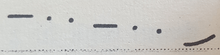

Lilias Armstrong and her colleague Ida C. Ward published their book Handbook of English Intonation in 1926.[103] It was accompanied by three double-sided gramophones which consisted of Armstrong and Ward reading English passages.[104] These recordings appeared in bibliographies of speech and theatre training for decades.[105] Armstrong and Ward analyzed all English intonation patterns as essentially consisting of just two "Tunes":[106] Tune 1 is typified by ending in a fall,[106] and Tune 2 by ending in a rise.[107] Kenneth Lee Pike called their analysis "valuable" for learners of English because it found commonalities in the various uses of rising contours and of falling contours.[108] In 1943, C.A. Bodelsen wrote "there is fairly general agreement" about the Tune 1 and Tune 2 classification;[109] he also compares the Tune 1 and Tune 2 system of Handbook of English Intonation with the intonation classifications in An Outline of English Phonetics by Daniel Jones and English Intonation by Harold E. Palmer.[110] Armstrong and Ward transcribed intonation in a system where lines and dots correspond to stressed and unstressed syllables, respectively, and vertical position corresponds to pitch.[111] Their method of transcribing intonation was anticipated by the one used in H. S. Perera and Daniel Jones's (1919) reader for Sinhalese,[112] and the preface to Handbook of English Intonation notes an inspiration in Hermann Klinghardt's notation for intonation.[113] Klinghardt said his book would have been impossible without Daniel Jones; his exercises also share similarities to Jones's intonation curves.[114] Armstrong and Ward used a system of discrete dots and marks to mark the intonation contour because it was easier for learners of English to comprehend than a continuous line.[115]

Handbook of English Intonation had a lasting impact for decades, particularly in regards to teaching English.[116] Pike wrote that the work was "an influential contribution to the field";[108] in 1948, he described it as providing "the most widely-accepted analysis of British intonation."[117] Armstrong and Ward's book remained in print and in use at least up until the 1970s.[118] Despite its popularity, however, its analysis has been criticized for being overly simplistic.[119] Jack Windsor Lewis wrote their handbook made "little or no advance in analysing the structure of English intonation", and criticised their system for notating intonation for having "so much superfluous detail."[118] Pike wrote their tune-based intonation "proves insufficient to symbolize adequately (i.e. structural) the intricate underlying system of contours in contrast one with another."[120] Armstrong and Ward themselves wrote that they were aware there is "a greater wealth of detail than are here recorded", but that "attention has been concentrated on the simplest forms of intonation used in conversation and in the reading of narrative and descriptive prose" since the book's intended reader is a foreign learner of English.[121]

French phonetics and intonation

In 1932 she wrote The Phonetics of French: A Practical Handbook.[122] Its stated goals are "to help English students of French pronunciation and especially teachers of French pronunciation."[123] To this end, it contains various practice exercises and teaching hints.[124] In the first chapter, she discusses techniques for French teachers to conduct ear-training exercises which were such an important part of her own teaching of phonetics.[125] The influences of Daniel Jones's lectures on French phonetics can be seen in Armstrong's discussion of French rhotic and stop consonants.[126] Armstrong's publication of this well-received book "widened the circle of her influence",[127] and in 1998, Ian Catford wrote he believed this book to still be the "best practical introduction to French phonetics."[51]

Chapter XVII of The Phonetics of French was about intonation,[128] but her main work on the topic was the 1934 book Studies in French Intonation co-written her colleague Hélène Coustenoble.[129] This book was written for English learners of French and provided the first comprehensive description of French intonation.[130] French intonation was also analyzed in terms of tunes;[131] it was a configuration-based approach, where intonation consists of a sequence of discrete pitch contours.[132] French intonation essentially consists of three contours in their analysis, namely: rise-falling, falling, and rising.[133] Armstrong and Coustenoble made use of a prosodic unit known as a Sense Group, which they defined as "each of the smallest groups of grammatically related words into which many sentences may be divided".[134] The book also provides discussion of English intonation in order to demonstrate how French intonation differs.[135] One contemporary review noted that "it seems to have received a favourable reception" in England.[136] The book contained numerous exercises, which led to another reviewer calling it "an excellent teaching manual" as well.[137] Alfred Ewert called the book "very useful" in 1936,[138] Elise Richter called it "an admirable achievement" in 1938,[139] and Robert A. Hall, Jr. called the book "excellent" in 1946.[140] It has been later described as "highly idealized" for beıng based on conventions of reading French prose out loud.[141] It is considered to be a "classic work on French intonation".[142]

Somali

Armstrong started doing phonetic research on Somali in 1931.[144] She published a Somali specimen for Le Maître Phonétique in 1933,[145] as well as a translation of "The North Wind and the Sun" for the 1933 Italian version of Principles of the International Phonetic Association,[146] but her main work on Somali was "The Phonetic Structure of Somali", published in 1934.[147] Her research was based on two Somalis, and she gives their names as "Mr. Isman Dubet of Adadleh, about 25 miles northeast of Hargeisa, and Mr. Haji Farah of Berbera";[148] in Somali orthography, these names would be Cismaan Dubad and Xaaji Faarax.[149] These men were apparently sailors living in the East End of London, and Armstrong likely worked with them from 1931 to 1933.[74] Farah's pronunciation had been the basis for Armstrong's 1933 specimen,[150] and he had also been the subject for a radiographic phonetic study conducted by Stephen Jones.[151]

Armstrong's analysis influenced a report by Bogumił Andrzejewski and Musa Haji Ismail Galal, which in turn influenced Shire Jama Ahmed's successful proposal for the Somali Latin alphabet.[152] In particular, Andrzejewski gave credit to her for the practice of doubled vowels to represent long vowels in Somali.[153] However, Andrzejweski did mention some disadvantages of Armstrong's orthography proposal with respect to vowels, writing that "Armstrong's system is too narrow to deal with the fluctuations in the extents of Vowel Harmony and so rigid that its symbols often imply pauses (or absence of pauses) and a particular speed and style of pronunciation."[154] He also claimed that Armstrong's orthographic proposal for Somali vowels would be "too difficult for the general public (both Somali and non-Somali) to handle."[155]

In 1981, Larry Hyman called Armstrong's paper "pioneering"; she was the first to thoroughly examine tone or pitch in Somali.[156] She analyzed Somali as being a tone language with four tones: high level, mid level, low level, and falling,[157] and she provided a list of minimal pairs which are distinguished by tone.[158] August Klingenheben responded to Armstrong's work in a 1949 paper.[159] He called Armstrong's work "an excellent phonetic study",[160] but argued that Somali was not a true tone language but rather a stress language.[161] Andrzejewski wrote in 1956 that Armstrong's phonetic data were "more accurate than those of any other author on Somali";[162] he analyzed Somali as being "a border-line case between a tone language and a stress language",[163] making use of what he called "accentual features".[162] There remains a debate as to if Somali should be considered a tone language or a pitch accent language.[164]

Armstrong was the first to describe the vowel system of Somali.[165] A 2014 bibliography on the Somali language called Armstrong's paper "seminal" and notes she provides a more detailed description of Somali vowels than other works.[166] She was also the first to discuss vowel harmony in Somali;[167] her vowel harmony analysis was praised by Martino Mario Moreno.[168] Roy Clive Abraham wrote that he agreed with Armstrong on most parts regarding Somali phonetics: "there are very few points where I disagree with her".[169] Werner Vycichl wrote that Armstrong's study "opens a new chapter of African studies".[170] In 1992, John Ibrahim Saeed said Armstrong's paper was "even now the outstanding study of Somali phonetics",[171] and in 1996, Martin Orwin wrote that it "remains essential reading for anyone interested in pursuing any aspect of the sound system of Somali."[172]

Kikuyu

Armstrong wrote a brief sketch of Kikuyu phonetics for the book Practical Phonetics for Students of African Languages by Diedrich Westermann and Ida C. Ward.[173] Her linguistic consultant was a man whom she refers to as Mr. Mockiri.[174] She also wrote a sketch on Luganda phonetics for this book.[175] Her main work on Kikuyu was The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu published posthumously in 1940.[176] Jomo Kenyatta, who would later become the first President of Kenya, was Armstrong's linguistic consultant for this book. He was employed by the Phonetics Department from 1935 to 1937 in order for Armstrong to carry out her research;[177] this was while Kenyatta was studying social anthropology at the London School of Economics under Bronisław Malinowski.[178] The book was largely finished when Armstrong died; only Chapter XXII "Tonal Forms of Adjectives" remained to be written, although Armstrong had already written notes for it. Daniel Jones entrusted Beatrice Honikman to write the remaining chapter and finalize the book's preparations for its 1940 publication; she was a Lecturer at SOAS who had earlier done work on Kikuyu with Kenyatta and she was also once Armstrong's student.[177] Chapter IV "The Consonant Phonemes" contains twelve kymograph tracings of Kikuyu words to illustrate phonetic details;[179] the phonetic kymograph was an important instrument for experimental phonetic research at University College under Jones.[180]

The book contains an appendix in which Armstrong proposes an orthography for Kikuyu.[181] She suggested that voiced dental fricative [ð] be represented by ⟨d⟩ and the prenasalized plosive [ⁿd][lower-alpha 6] by ⟨nd⟩; in parallel were the pairs [β][lower-alpha 7] ⟨b⟩ / [ᵐb] ⟨mb⟩ and [ɣ] ⟨g⟩ / [ᵑg] ⟨ŋg⟩.[186] Westermann and Ward also advocated the use of ⟨d⟩ for [ð] in their book.[187] Kenyatta though Kikuyu people would not accept the use of ⟨d⟩ for [ð] because in the other orthographies Kikuyu people would be familiar with, namely English and Swahili, ⟨d⟩ represents a stop consonant, not a fricative; Armstrong noted there did not seem to be any objection to using ⟨b⟩ and ⟨g⟩ to represent fricatives in Kikuyu orthography even though they represent stops in English.[188] The use of ⟨d⟩ for [ð] has also been criticised as there is no alternation between [ð] and [ⁿd] in Kikuyu unlike the other two pairs; furthermore the Kikuyu voiced dental fricative phonologically patterns with voiceless fricatives instead of with other voiced ones.[189] Armstrong also proposed that the seven vowels of Kikuyu be represented by the IPA symbols ⟨i, e, ɛ, a, ɔ, o, u⟩;[190] this followed the practical orthography, now known as the Africa Alphabet, devised by the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures.[191] This system avoided the use of diacritics which Armstrong called "tiresome",[192] and which often were omitted when writing.[193] A drawback to this system is that it is less faithful to etymology and obscures the relationship with related languages.[194] Kikuyu leaders also did not like the use of the specialized phonetic symbols ⟨ɛ⟩ and ⟨ɔ⟩, finding them impractical since they could not easily be written on a typewriter.[195] Armstrong also proposed that the velar nasal be written with the letter ⟨Ŋ, ŋ⟩ and that the palatal nasal be written with the digraph ⟨ny⟩ (although she wrote she personally would prefer the letter ⟨Ɲ, ɲ⟩).[196] The education authorities in Kenya briefly recommended that schools use Armstrong's system.[197] In modern Kikuyu orthography, the voiced dental fricative is written ⟨th⟩, the velar and palatal nasals are respectively as ⟨ng'⟩ and ⟨ny⟩, and the vowels [e, ɛ, o, ɔ] are respectively written ⟨ĩ, e, ũ, o⟩.[198]

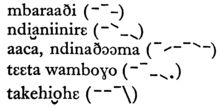

- horse "mid, high, fairly-low—all level tones"

- Didn't he finish? "mid, high-mid fall, low, low fall"

- No, I didn't read it "high, low-mid rise, mid, high, high-mid fall, mid"

- Do call Wambogo "mid, high, low, low fall, very-low fall"

- Do please hurry up "mid, mid, high, high-low fall"[199]

Armstrong's book provided the first in-depth description of tone in any East African Bantu language.[200] Throughout the book, Armstrong represented tone with a pictorial system; a benefit of this method was that she did not need to have a tonemic analysis.[201] A sequence of dashes at varying heights and angles accompanied each word or sentence throughout the book.[199] Armstrong's description of Kikuyu tone involved grouping stems into tone classes; each tone class was defined in terms of its tonal allomorphy depending on surrounding context. Subclasses were based on properties like length or structure of the stem.[202] Armstrong discussed five tone classes for verbs, named Tonal Class I–V, and a small group of verbs which do not belong to any of those five classes,[203] seven tone classes for nouns, each named after a word in that class, e.g., the moondo Tonal Class (Kikuyu: mũndũ "person"),[204] and three tone classes for adjectives, each named after a stem in that class, e.g., the ‑ɛɣa Tonal Class (Kikuyu: ‑ega "good").[205] William J. Samarin noted Armstrong conflated tone and intonation for the most part; he claimed this led to "exaggerated complexities" in her description, particularly with respect to the final intonational fall in interrogatives.[206] When Armstrong wrote her manuscript, analysis of tone was a nascent field and the complex relationship between phonemic tonemes and phonetic pitch led phoneticians to analyze languages as having large numbers of tones.[207] In 1952, Lyndon Harries was able to take Armstrong's data and analyze Kikuyu tone as only having two underlying tone levels.[208] Mary Louise Pratt also re-analyzed Armstrong's Kikuyu data as only having two levels.[209] Pratt also noted Armstrong does not distinguish allophonically long vowels from vowels which are phonemically long.[210] Kevin C. Ford wrote that if Armstrong had not died before completing this book "there is no doubt she could have expanded her range of data and probably presented some rigorous analysis, which is sadly lacking in the published work."[211] The phonologist Nick Clements described Armstrong's book in a 1984 paper as "an extremely valuable source of information due to the comprehensiveness of its coverage and accuracy of the author's phonetic observations."[212]

Personal life

She married Simon Charles Boyanus (Russian: Семён Карлович Боянус, translit. Semyón Kárlovich Boyánus; 8 July 1871 – 19 July 1952)[213] on 24 September 1926,[214] although she still continued to go by "Miss Armstrong" professionally after marriage.[215] Boyanus was a professor of English philology at the University of Leningrad, where he worked with Lev Shcherba.[216] He came to the University College Phonetics Department in 1925, where he spent eight months learning English phonetics under Armstrong.[217]

After marriage, Boyanus had to return to the Soviet Union for eight years, while Armstrong had to stay in England.[217] While away, Boyanus worked with Vladimir Müller to produce English–Russian and Russian–English dictionaries.[217] Armstrong assisted with the phonetic transcription for the keywords in the English–Russian volume.[218] Armstrong was able to visit Boyanus in Leningrad on two occasions, and he was able to briefly return to London in 1928. Boyanus was finally able to permanently move to England in January 1934, whereupon he became a lecturer in Russian and Phonetics at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at the University of London.[215][217]

While working at University College, Armstrong lived in Forest Gate[27] and Church End, Finchley.[219]

Death

In November 1937, Armstrong became sick with a persistent bout of influenza.[220] Her condition worsened and at the age of 55 on 9 December 1937, she died at Finchley Memorial Hospital, Middlesex, following a stroke.[221] There was a service for her at Golders Green Crematorium at noon on 13 December.[222][223] The University College Provost, Secretary, and Tutor to Women Students were among those present at her funeral.[224] Her obituary was printed in The Times,[225] The New York Times,[226] Nature,[227] Le Maître Phonétique,[228] the Annual Report for University College,[229] and other journals;[230][231] her death was also reported in Transactions of the Philological Society,[232] among other publications.[233][234][235]

In early 1938, when her widower Simon Boyanus brought up the possibility of publishing Armstrong's Kikuyu manuscript, Daniel Jones arranged for Beatrice Honikman to see it through to publication.[236] Jones was reportedly "deeply affected" by Armstrong's death;[237] he wrote Armstrong's obituary for Le Maître Phonétique,[238] and his preface to The Phonetic Structure of Kikuyu paid homage to her life.[239] When the University College phonetics library had to be restocked after being bombed in World War II during the London Blitz, Jones donated a copy of Armstrong's posthumously published book "as a fitting start in the reconstruction of the Phonetics Departmental Library".[240]

Selected works

- Main article: Lilias Armstrong bibliography, which also contains citations to contemporary reviews of Armstrong's books.

- Armstrong, L. E. (1923). An English Phonetic Reader. The London Phonetic Readers. London: University of London Press.

- Armstrong, L. E.; Pe Maung Tin (1925). A Burmese Phonetic Reader: With English translation. The London Phonetic Readers. London: University of London Press.

- Armstrong, L. E.; Ward, I. C. (1926). Handbook of English Intonation. Cambridge: Heffer. [Second edition printed in 1931.]

- Armstrong, L. E. (1932). The Phonetics of French: A Practical Handbook. London: Bell.

- Armstrong, L. E. (1934). "The Phonetic Structure of Somali". Mitteilungen des Seminars für orientalische Sprachen zu Berlin. 37 (Abt. III, Afrikanische Studien): 116–161. [Reprinted in 1964, Farnborough: Gregg. hdl:2307/4698]

- Coustenoble, H. N.; Armstrong, L. E. (1934). Studies in French Intonation. Cambridge: Heffer.

- Armstrong, L. E. (1940). The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu. London: International African Institute.

Footnotes

- ↑ Prior to 1927 the stress diacritic in the International Phonetic Alphabet was an acute mark ˊ instead of a vertical line ˈ.[56]

- ↑ The journal Le Maître Phonétique was written entirely in phonetic transcription, using the International Phonetic Alphabet; the official language of the journal was French, although many articles were written in English.[63] In contrast to modern conventions,[64] phonetic transcriptions at this time were not regularly placed in brackets.

- ↑ In Armstrong's IPA transcription of Swedish, the acute mark ˊ and caron ˇ are tone letters before a word to denote Swedish pitch accent. The acute mark represents Tone 1 or Acute Accent; the caron represents Tone 2 or Grave Accent (what Armstrong refers to as "kɒmpaʊnd toʊn" [compound tone]).[67] This convention is discussed in §51 of the 1912 edition of The Principles of the IPA[68] and §36 of the 1949 edition.[69]

- ↑ In Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin's IPA transcription of Burmese, ˺ represents "slightly falling" tone and its vertical position denotes whether it's high or low (p. 21); ˍ represents a low, level tone (pp. 22–23); and ˋ represents a high falling tone (pp. 24–25). These tone letters appeared before the syllable whose tone they describe. The symbol ˈ denotes "a weak closure of the glottis" (p. 22), and ȷ represents a phoneme typically realized as a palatal approximant (pp. 18–19).

- ↑ A similar system for marking tone and intonation was used for the texts in Armstrong 1934 and Armstrong 1940 although the staff in the latter lacked a centre-line. The numbers in the image refer to footnotes.

- ↑ Armstrong uses digraphs, e.g., ⟨nd⟩, to transcribe prenasalized stops in Kikuyu. She writes "It is phonetically sound to consider mb, nd, ŋg and nj as a single consonant sound with a nasal 'kick-off' and to regard these as phonemes of the language. A single symbol might be used to represent each of these phonemes, and thus the ideal of one letter per phoneme would be achieved. In this book, however, digraphs are used."[182]

- ↑ Armstrong uses the symbol ⟨ʋ⟩ instead of ⟨β⟩ to represent the "weak bi-labial voiced fricative" in Kikuyu.[183] This was consistent with Practical Orthography of African Languages[184] and had been the convention of the IPA prior to 1927.[185]

Citations

- ↑ Photo source: Collins & Mees 1999, between pp. 256 & 257.

- ↑ Jones 1938, p. 2. "mis Armstrong wəz wʌn əv ðə fainist founitiʃnz in ðə wəːld."

- ↑ Asher 2015. "Armstrong, Lilias Eveline (1882–1937), phonetician, born on 29 September 1882 at 152 Eccles New Road, Pendlebury, near Manchester, was the daughter of James William Armstrong, Free Methodist church minister, and his wife, Mary Elizabeth Armstrong, née Hunter."

- ↑ "Newmarket Council School, Louth", National School Admission Registers & Log-books 1870–1914, n.d. [Date of Admission: 9 September 1889], Admission Number: 264 (See also #261–263, 265) – via Findmypast,

Address: 18 Lee St Louth; […] Last School: Southend Bd. Middlesborough. Highest Standard there presented: Inf; In what Class at Admission: I.

- ↑ Armstrong 1923, p. vii. "I have recorded as possible my own pronunciation, which is not in any way extreme, and which may be heard, with unimportant differences, from many educated speakers of the south east and of other parts of England. Readers will notice the influence of the north […]. "

See discussion of Armstrong's accent in:- Jones, Daniel (1963). Everyman's English Pronouncing Dictionary (12th ed.). London: Dent. p. xxix.

- Windsor Lewis, Jack (1985). "British Non-Dialect Accents". Zeitschrift für Anglistik und Amerikanistik. 33 (3): 248.

- 1 2 Asher 2015. "Armstrong graduated in 1908 as BA of the University of Leeds, where she was a king's scholar and where her principal subjects were French and Latin."

- ↑ Collins & Mees 2006, p. 478. "After taking her B.A. at Leeds in French and Latin, she went on to a highly successful career as a teacher of French. She abandoned school teaching in 1918 to join Daniel Jones's department of phonetics at University College London […] ."

- ↑ "Bachelor of Arts". Graduates of the University of Leeds. The University of Leeds Calendar. 1906–1907: 375. 1906.

1906 Armstrong, Lilias Eveline

See also: Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47 and Gimson 1977, p. 4. (Asher 2015 gives 1908 as the year she got her B.A., however.) - ↑ Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47. "She was trained as a teacher at Leeds University, obtaining a B.A. degree there in 1906 […] ."

- ↑ "Boyanus, Lilias Eveline (née Armstrong)", Teachers' Registration Council Registers 1914–1948, n.d. [Date of Registration: 1 July 1916], Register Number: 17497 – via Findmypast,

Attainments: B.A., Leeds. Board of Education Certificate. Training in Teaching: University of Leeds Day Training College.

- 1 2 Sources disagree as to the name of the school or schools she taught at, how long she taught, and what her positions were:

- Teachers' Registration Council Registers. "Experience: Assistant Mistress—[3 illegible words: seven, six, and seven characters long, respectively] School, East Ham, 1906–1910; Senior Assistant Mistress—Higher Elementary School, East Ham, 1910–1918."

- Jones, Daniel (1932). Foreword. The Phonetics of French: A Practical Handbook. By Armstrong, Lilias E. London: Bell. p. iii.

Moreover, she had seven years' experience as a teacher of French in schools before she was appointed to her present post at University College, London (which she has held since 1918).

- The Times & 11 Dec. 1937, p. 19. "After graduating at Leeds she started her career as a teacher of French and was senior assistant at the Higher Elementary School, East Ham, from 1906 to 1918. During the latter part of that period she studied phonetics with the object of improving her teaching of spoken French. Eventually it became evident that phonetics itself was her true vocation, and she was appointed to the staff of the Department of Phonetics, University College, London, in 1918."

- Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47. "She was trained as a teacher at Leeds University, obtaining a B.A. degree there in 1906, and between 1910 and 1918 she taught at the East Ham Central School in London, where she was highly regarded and was expected to be appointed headmistress."

- Asher 1994, p. 221. "Before then she had a successful career as a secondary school teacher of French and had reached the position of senior mistress at East Cheam Central School in Essex."

- Collins & Mees 1999, p. 194. "At the time when, in her mid-thirties, she first attended Jones's Department as a part-time student, she held the post of senior mistress at East Ham Central School in metropolitan Essex. She had been highly successful in her career as a teacher and was widely tipped for promotion to headmistress."

- Asher 2015. "Her first appointment after graduation was as a teacher of French at the higher elementary school, East Ham, London. She was senior mistress there when she left in 1918 for University College, London, to become full-time assistant to Daniel Jones (1881–1967) in the department of phonetics. In making this move, after having been fired with enthusiasm for phonetics through attending evening classes in the subject at University College, Armstrong left a secure position, from which she could without doubt have expected to acquire a post as headmistress, for a temporary appointment with a lower salary."

- ↑ Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47. "However, in her mid-thirties she developed a great interest in phonetics and studied for London University extension examinations, which led first to a Diploma in French Phonetics in 1917 and then to one in English Phonetics in 1918, with a Distinction in both."

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 287. "The move, when it came in 1922, was to much more modest accommodation—a Victorian terraced house, backing on to the main buildings of University College and overlooking the gardens of a Bloomsbury square. Number 21 Gordon Square, known for many years in the College as "Arts Annexe I", was to be the home of the UCL Phonetics Department for the rest of Jones's career (apart from the interruption of the war years)."

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 183 & 194.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 195.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1948). "The London School of Phonetics". Zeitschrift für Phonetik und allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft. 2 (3/4): 128. doi:10.1524/stuf.1948.12.jg.391.

At first owing to financial difficulties only part-time assistants for evening work could be appointed. There was no full-time assistant for phonetics until 1918, when Miss L. E. ARMSTRONG became a member of the Staff.

- ↑ Teachers' Registration Council Registers. "Experience: […] Assistant in Department of Phonetics—University College, W.C.1., 1918–1920; Lecturer in Department of Phonetics—University College, W.C.1., 1920–1921; Senior Lecturer in Department of Phonetics—University College, W.C.1., 1921–."

- ↑ Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47; Asher 2015; Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 283–284, 319; Teachers' Registration Council Registers. (Collins & Mees 1999, p. 195 and Gimson 1977, p. 3 say she became senior lecturer in 1920, however.)

- ↑ Nature 1938; Gimson 1977, p. 4; Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47. (Asher 2015 gives 1936 as the year she got Readership, however.)

- ↑ "London, May 19". University News. The Times (47689). London. 20 May 1937. col D, p. 11.

The title of Reader in Phonetics was conferred on Miss Lilias E. Armstrong, B.A. (Leeds), in respect of the post held by her at University College.

- ↑ R. E. G. (November 1937). "University of London–University College". Home University News. The Universities Review. 10 (1): 73.

We are glad also to offer our best wishes to Miss L. Armstrong […] upon [her] appointment[] to Readership[] in Phonetics […].

- ↑ School of Oriental Studies (1937). "Former Teachers of the School". Appendix. The Calendar of the School of Oriental Studies (University of London). For the Twenty-Second Session 1937–8: 242.

Lilias E. Armstrong, B. A. Additional Lecturer in Phonetics. 1917–25.

Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 47. "Close links between University College and its neighbours within the University of London, namely the School of Oriental and African Studies, where Lilias Armstrong gave some lectures, and the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, also provided an additional stimulus, offering her a wide experience of languages spoken outside Western Europe." - ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 281–282.

- ↑ Ashby, Michael G.; Ashby, Patricia (2009). "The London Phonetics Training of Masao Kanehiro (1883–1978)" (PDF). Journal of the English Phonetic Society of Japan. 13: 24. ISSN 1344-1086.

Kanehiro's entry form is endorsed with the initials "LEA" indicating that the staff member who interviewed and admitted Kanehiro was not Daniel Jones, but Lilias E. Armstrong.

- ↑ UCL 1938, pp. 33–34.

- 1 2 "Liste des membres de l'Association Phonetique Internationale. Janvier, 1925". Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 9 (Supplement): 2. January–March 1925.

Armstrong, Miss L., 190 Osborne Road, Forest Gate, London, E. 7

- ↑ "Modern Language Association". Modern Language Teaching. 15 (1): 30. February 1919.

The following twenty-two new members were elected on January 9: […] Miss L. E. Armstrong, B.A., University College, W.C. (Phonetics Department).

- ↑ Jones, Daniel; Fry, D. B., eds. (1936). "List of Members". Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 319.

Armstrong, Miss L. E., Department of Phonetics, University College, London.

- ↑ See, e.g., Plug 2004 and McLeod 2005.

- ↑ University College, London (1935). "Phonetics". Calendar, 1935–36: 60.

S 16. (Miss Armstrong.) Phonetics of Swedish. A Course of six Lectures with practical work.

- ↑ University of London (1935). "Phonetics". Instruction-Courses, 1935–1936. Regulations and Courses for Internal Students, 1935–36: 139.

S 12 (e) (Prof. D. Jones and Miss L. Armstrong.) Russian Phonetics with practical work.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 334, citing Departmental Prospectus, 1933–34.

- ↑ See, e.g., Chatterji 1968.

- ↑ Ward, Ida C. (1928). "The Phonetics Department: University College, London". Revue de Phonétique. 5: 48–50. See also Jones 1948, pp. 129–131 and Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 421–424.

- ↑ Ward 1928, p. 51.

- ↑ "From Here and There". Modern Language Teaching. 15 (3): 83. June 1919.

(3) Daily ear-training exercises, conducted by Miss L. E. Armstrong. (4) Daily practical classes—(a) pronunciation exercises

- ↑ "London Holiday Courses". Notes and News. English Studies. 1 (6): 179. 1919. doi:10.1080/00138381908596384.

Opinion on the course is fairly well represented by the admirably pointed remarks one correspondent has jotted down on a postcard: " […] Splendid I thought Miss Armstrong's ear-training exercises, and they have been a great help to me in teaching my 'beginners in English' this year. […] The course included: […] c. daily ear-training exercises, by Miss Amstrong [sic]. […]" […] From another report: "[…] The 'ear-test' lessons were splendid."

- 1 2 Grootaers, L, ed. (1921). "Engelsche vacantieleergangen" [English vacation courses] (PDF). Kroniek. Leuvensche Bijdragen. 13 (1–2): 134.

De lessen bestaan uit: 1. Twelve Lectures on English Phonetics (D. Jones en Miss Armstrong); 3 [sic]. Daily Ear-Training Exercises (Miss Armstrong); [...] — Vooral de Ear-Training Exercices moeten uitstekende resultaten opleveren : degenen die ze bijgewoond hebben, spreken er met veel lof over. Deze oefeningen bestaan hierin dat zinledige klankenreeksen met altijd toenemende moeilijkheid gedicteerd worden en door den hoorder phonetisch opgeschreven worden.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 287–288, citing J. P. Prins. 1921. "Vacantie-cursus te Londen", De School met den Bijbel: 139–140.

- ↑ "Cours de Vacances à Londres". Chronique Universitaire. Revue de l'Enseignement des Langues Vivantes. 38 (5): 225. May 1921.

Toutes les matinées seront occupées par des conférences (douze) de phonétique anglaise, par Mr. Daniel Jones et Miss L. E. Armstrong, et des exercices pratiques (ear-training, pronunciation, fluency practice) dirigés par des assistants du département de phonétique.

- ↑ Passy, P.; Jones, D., eds. (April–June 1930). "sa e la" [Çà et là]. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 30: 41.

fonetiks wil fɔːm ə prɔminənt fiːtʃər əv meni sʌmə vəkeiʃn kɔːsiz ðis jəː. ðe fɔlouiŋ mei bi speʃəli menʃənd: University College, London, Course of Spoken English for Foreigners, dʒulai 29θ–ɔːgəst 14θ (lektʃəz ɔn ðə fonetiks əv iŋgliʃ bai D. Jones, A. Lloyd James ənd Miss L. E. Armstrong); […]

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 333. "Figure 11.2. An advertisement for a 1935 vacation course."

- ↑ "Diary of Societies". Nature. 110 (2762): 500. 7 October 1922. doi:10.1038/110500b0.

Public Lectures. […] Wednesday, October 11. University College, at 5.30. […] Miss Lilias Armstrong : The Use of Phonetics in the Class Room. (As applied to the teaching of French.)

See also: "Arrangements for To-day". The Times (43159). London. 11 October 1922. col F, p. 13. - ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (July–September 1933). "The Technique of Speech". Good Speech. London: Verse Speaking Fellowship. 3: 2–5.

- ↑ Passy, P.; Jones, D., eds. (October–December 1925). "sa e la" [Çà et là]. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 12: 30.

Miss L. E. Armstrong lɛkʧəd ɒn ɪŋglɪʃ ɪntoneɪʃn ət Göteborg ɪn sɛptɛmbə, ənd ət Stockholm ɪn ɒktoʊbə.

- ↑ Furuhjelm, Åke (1929). "Protokolle des Neuphilologischen Vereins". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. 30 (1/2): 94. JSTOR 43345640.

§4. Miss Lilias E. Armstrong, Senior Lecturer of Phonetics in University College, London, hielt einen Vortrag über die Intonation im Englischen. Die Vortragende wies u. a. auf gewisse charakteristische Fehler in der englischen Intonation bei uns und in Schweden hin. Dem Vortrag, zu dem der Eintritt frei war, wohnte eine zahlreiche Zuhörerschaft bei.

- ↑ Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 48. "Lilias Armstrong gave lectures in Holland (1922), in Sweden (1925 and 1928) and in Finland and the Soviet Union (1928)."

- ↑ Chatterji, S. K. (April 1968). "A Personal Tribute to Professor Daniel Jones". Bulletin of the Phonetic Society of Japan. 127: 20.

There was Miss Lilias Armstrong and Miss Ida C. Ward who gave us very good drilling in Phonetics and also some schooling in general principles. I have kept notes of the words which they dictated to us (also Professor Jones), consisting of awful combinations of the most difficult sounds of human speech, and we were to hear them, identify them and put them down with the proper symbols.

- ↑ Plug, Leendert (2004). "The Early Career of J. R. Firth: Comments on Rebori (2002)". Historiographia Linguistica. 31 (2/3): 473–474. doi:10.1075/hl.31.2.15plu.

Firth's record at UCL indicates that he was in fact registered as a student there for two terms during the 1923–1924 session. He attended courses in […] French phonetics […]. This means that he was most probably taught by several UCL staff members who would later become his colleagues there, such as […] Lilias Armstrong (1882–1937) […] 11 […] 11. […] Armstrong lectured on French Phonetics, […] (University College Calendar, session 1923–1924).

- 1 2 Catford, John C. (1998). "Sixty Years in Linguistics". In Koerner, E. F. K. First Person Singular III: Autobiographies by North American Scholars in the Language Sciences. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. p. 7. doi:10.1075/sihols.88.02cat.

- ↑ Wade-Lewis, Margaret (Spring 1990). "The Contribution of Lorenzo Dow Turner to African Linguistics". Studies in Linguistic Sciences. 20 (1): 192.

He also worked each day with informants from West Africa and took advanced courses in phonetics with Daniel Jones and L. E. Armstrong (Turner, 1940:1).

- Citing Turner. 1940. Proposals by Lorenzo Turner for a study of Negro speech in Brazil. January. Evanston: Northwestern University Library, Turner Collection.

- ↑ Wade-Lewis, Margaret (2007). Lorenzo Dow Turner: Father of Gullah Studies. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-57003-628-6.

Mentioning others in London besides Ward with whom he interacted regularly in the academic enterprise, Turner affirmed his satisfaction with the opportunities available to him: 'I am also doing some advanced work in phonetics under Professor Armstrong of University College.'

- Citing Turner to Jones, November 15, 1936, Jones Collection, Box 42, Folder 10.

- ↑ Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, pp. 47–48. "The testimony of Professor Jean-Paul Vinay, the distinguished Canadian scholar, who was one of her students and later a colleague, is typical of the opinions held of her teaching skills. He praises her for her patience and kindness and says that she opened up for him a new world of acoustic and articulatory experience of which he was totally ignorant when he began his studies under her guidance. He remembers particularly her ability to imitate with apparent ease the most exotic sounds of any of the languages she used as illustrations in her classes."

- ↑ McLeod, A. L. (2005). R. G. Howarth: Australian Man of Letters. Elgin, IL: New Dawn Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-932705-53-9.

The registrar of the University of London, Martin Butcher, kindly provided the following information: 'Mitchell was admitted to UCL in October 1937 for a PhD in English, which he completed in September 1938. […] In 1937–38 he also took a certificate course entitled 5.1 English Phonetics for English Students....It was 'A Course of General Phonetics, with Practical exercises, adapted to the needs of Students desirous of undertaking research work.' It was offered by the department of Phonetics, then headed by Professor Daniel Jones, and was taught by Miss Lilias E. Armstrong (Reader), Miss Eileen M. Evans (Assistant Lecturer), and Mr. N. C. Scott (Lecturer).'

- ↑ Passy, Paul (April–June 1927). "desizjɔ̃ dy kɔ̃sɛːj rəlativmɑ̃ o prɔpozisjɔ̃ d la kɔ̃ferɑ̃ːs də *kɔpnag" [Décisions du conseil relativement aux propositions de la conférence de Copenhague]. artiklə də fɔ̃. Le Maître Phonétique. 18: 14.

(2) i desid kə l aksɑ̃ d fɔrs səra dezɔrmɛ rəprezɑ̃te par yn liɲ vɛrtikal ˈ də preferɑːs a la liɲ ɔblik ɑ̃plwaje ʒyska prezɑ̃; e kə ˌ səra ɑ̃plwaje pur rəprezɑ̃te l aksɑ̃ zgɔ̃dɛːr. (puːr 11, kɔ̃ːtr 2, nɔ̃ vɔ̃tɑ̃ 3.)

- Discussed in: Wells, John (13 February 2008). "Phonetic incunabula". John Wells's phonetic blog archive 1–14 February 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

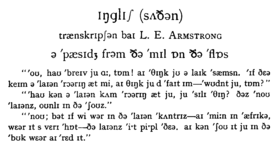

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1921). "ɪŋglɪʃ (sʌðən): ə ˊpæsɪdʒ frəm ðə ˊmɪl ɒn ðə ˊflɒs" [English (Southern): A passage from The Mill on the Floss]. Textes pour nos élèves. 1: 3–4.

- 1 2 Collins & Mees 1999, p. 309.

- ↑ "Publications of the International Phonetic Association". Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 4. Back cover. October–December 1923.

- ↑ For example, Armstrong 1921. See also: Lilias Armstrong bibliography § Transcription passages for students.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 311. "Lilias Armstrong's name does not appear on the cover until the July 1923 issue, where she is listed as "Secrétaire de Rédaction", a post which she held until 1936."

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 311. "A crucial factor was that in London there was also someone who was energetic, competent and willing to mobilise the process of restoring the journal and the Association to life. This was Jones's trusted assistant, now a senior lecturer, Lilias Armstrong."

- ↑ Hirst, Daniel (2010). "Sample Articles from Le Maître Phonétique". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 40 (3): 285–286. doi:10.1017/S0025100310000150.

- ↑ International Phonetic Association (1989). "Report on the 1989 Kiel Convention". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 19 (2): 68. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003868.

The Association recommends that a phonetic transcription should be enclosed in square brackets [ ].

- ↑ For example, Armstrong 1926. See also: Lilias Armstrong bibliography § Book reviews.

- ↑ "tablə de matjɛːr". Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 9. January–March 1925.

- ↑ Armstrong 1927, p. 20.

- ↑ Passy, Paul; Jones, Daniel, eds. (September–October 1912). "The Principles of the International Phonetic Association". Le Maître Phonétique (Supplement): 13.

- ↑ International Phonetic Association (2010). "The Principles of the International Phonetic Association (1949)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 40 (3): 319 [19]. doi:10.1017/S0025100311000089.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (April–June 1927). "swiˑdɪʃ" [Swedish]. spesimɛn [Spécimens]. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 18: 20–21.

- ↑ Björkhagen, Immanuel (1923). "Preface". Modern Swedish Grammar. Stockholm: Norstedts. p. 5.

I have enjoyed the valuable assistance of Prof. Daniel Jones and Miss Lilias E. Armstrong, B. A., of the Phonetics Department, University College. Miss Armstrong has also kindly undertaken to read the proofs of the phonetic part of this book for which I here beg to express my sincere thanks.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (October–December 1929). "rʌʃn" [Russian]. spesimɛn [Spécimens]. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 28: 47–48.

- ↑ Trofimov, M. V.; Jones, Daniel (1923). "Note". The Pronunciation of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. vi.

- 1 2 Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 48.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (July–September 1926). "[Review of Gairdner, W. H. T. (1925). The Phonetics of Arabic. Oxford University Press.]". kɔ̃trɑ̃dy. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 15: 28–29.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1923). An English Phonetic Reader. The London Phonetic Readers. London: University of London Press.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E.; Pe Maung Tin (1925). A Burmese Phonetic Reader: With English translation. The London Phonetic Readers. London: University of London Press.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1972). "Appendix A: Types of Phonetic Transcription". An Outline of English Phonetics (9th ed.). Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. p. 345; Collins & Mees 1999, p. 204.

- ↑ Palmer, H. E.; Martin, J. Victor; Blandford, F. G. (1926). "Introductory". A Dictionary of English Pronunciation with American Variants (In Phonetic Transcription). Cambridge: Heffer. p. ix.

By "narrower system of English phonetic notation" is meant any system that makes use of the symbols [ɪ], [ɛ], [ɒ], [ʊ], [ɜ]. For some years past the tendency to use the narrower system has been increasing. The Maître Phonétique, the organ of the International Phonetic Association, makes exclusive use of it, as does also the supplement Textes pour nos élèves.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1950). The Phoneme: Its Nature and Use. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. pp. 166–168. Jones 1972, pp. 341–342. Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 451.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1922) [1st ed. c. 1918]. An Outline of English Phonetics (2nd ed.). New York: G. E. Stechert. pp. V–VI, VIII.

- ↑ Armstrong 1923, pp. vii–xii.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (July–September 1923). "ə næroʊə trænskrɪpʃn fər ɪŋglɪʃ" [A narrower transcription for English]. artiklə də fɔ̃. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 3: 17–19.

ɪt ɪz hoʊpt ðət mɛmbəz əv ðɪ a.f. wɪl rɪəlaɪz ðə juˑsflnəs əv ðɪ ɛkstrə sɪmblz, ənd wɪl teɪk ðə trʌbl tə lɜːn ðəm.

Quote from page 19. - ↑ Windsor Lewis, J. (1972). "The Notation of the General British English Segments". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 2 (2): 60. doi:10.1017/S0025100300000505.

This was the direct descendant of what Daniel Jones called 'narrow' transcription. This he devised in 1916 and demonstrated in various contributions to Le Maître Phonétique chiefly from 1923 onwards for some years. It was at first best known in the joint and individual work of Lilias Armstrong and Ida Ward (Armstrong, 1923; Armstrong–Ward, 1926; Ward, 1929, etc.).

- ↑ Armstrong 1923, p. x.

- ↑ Armstrong & Pe Maung Tin 1925, p. 37, Firth 1933, p. 40, and Watkins 2001, p. 294. Text is the Burmese translation of the words "the north wind and the sun", as written in the titles of their transcriptions of the fable.

- ↑ Allott, Anna (2004). "Professor U Pe Maung Tin (1888–1973): The Life and Work of an Outstanding Burmese Scholar" (PDF). Journal of Burma Studies. 9: 15. doi:10.1353/jbs.2004.0001.

- ↑ Pe Maung Tin (January–March 1924). "bɜˑmiːz" [Burmese]. spesimɛn [Spécimens]. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 5: 4–5.

- ↑ Cornyn, William (1944). "Outline of Burmese Grammar". Language. 20 (4, Suppl). doi:10.2307/522027.

Armstrong and Tin, A Burmese Phonetic Reader, London 1925, contains an elaborate description of the phonetics of the language.

- ↑ Okell, John (1971). A Guide to the Romanization of Burmese. London: Royal Asiatic Society. p. 11.

In time the scientific principles and precise symbols of the International Phonetic Association were applied to the study and transcription of Burmese. […] [I]t was first applied in detail to Burmese in 1925 by Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin. Their system was very detailed: it required the use of some fourteen special phonetic symbols and five diacritics involving some placed at various heights above the line.

For details on their system for transcribing Burmese tone see Armstrong & Pe Maung Tin 1925, pp. 19–26 or Pe Maung Tin 1924. - ↑ Reynolds, H. O. (1927). "[Review of Armstrong & Pe Maung Tin 1925]". Journal of the Burma Research Society. 17: 119–125.

- ↑ Pe Maung Tin (1930). "A Burmese Phonetic Reader". Journal of the Burma Research Society. 20 (1): 50.

- ↑ Armstrong & Pe Maung Tin 1925, p. 17. "sh as in ˍshiː (oil). Strongly aspirated s. The distance between the tongue and the teeth-ridge is greater than that for s."

- ↑ Pe Maung Tin 1930, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Brown, R. Grant (1925). "Books on Burma and Siam". Notices of Books. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 57 (4): 737. JSTOR 25220835. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00169060.

- ↑ Brown, R. Grant (1925). Burma As I Saw It: 1889–1917. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. p. 24.

- ↑ Firth, J. R. (1933). "Notes on the Transcription of Burmese". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 7 (1): 137. JSTOR 607612. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00105488.

- ↑ Latt, Minn (1958). "The Prague Method Romanization of Burmese". Archiv Orientální. 26: 146.

Since the system of Lilias E. Armstrong and Pe Maung Tin contains more unfamiliar symbols than that of William Cornyn's the latter's method has been taken as the basis.

- ↑ Watkins, Justin W. (2001). "Burmese". Illustrations of the IPA. Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 31 (2): 291–295. doi:10.1017/S0025100301002122.

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. 13: "hiˑ z ə ˊvɛrɪ ˊwʌndəfl ˊpɪənɪst."

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. 24: "ˊhæv ju biˑn ˊsteɪɪŋ ðɛə ˊlɒŋ?"

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E.; Ward, I. C. (1926). Handbook of English Intonation. Cambridge: Heffer. [Second edition printed in 1931.]

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. VIII.

- ↑ For example:

- Thonssen, Lester; Fatherson, Elizabeth; Thonssen, Dorothea, eds. (1939). Bibliography of Speech Education. New York: H. W. Wilson. pp. 469, 503.

- Voorhees, Lillian W.; Foster, Jacob F. (1949). "Recordings for Use in Teaching Theatre". Educational Theatre Journal. 1 (1): 70. JSTOR 3204109.

- Cohen, Savin (1964). "Speech Improvement for Adults: A Review of Literature and Audio‐visual Materials". The Speech Teacher. 13 (3): 213. doi:10.1080/03634526409377372.

- 1 2 Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. 4.

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. 20.

- 1 2 Pike, Kenneth L. (1945). The Intonation of American English. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 7.

- ↑ Bodelsen, C. A. (1943). "The Two English Intonation Tunes". English Studies. 25: 129. doi:10.1080/00138384308596744.

- ↑ Bodelsen 1943, p. 129. See also Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 429–433 for discussion of the influence Jones and his colleagues had on each other with respect to intonation.

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, pp. IV, 2.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 273. "The extract reproduced in Figure 9.6 [from Perera, H. S.; Jones, Daniel (1919). Colloquial Sinhalese Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press.] shows that the system appears to foreshadow mutatis mutandis the intonation marking scheme for English produced by Armstrong–Ward (1926)."

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. IV.

- ↑ Pike 1945, p. 175. "I have only seen the second edition (Leipzig, 1926), in which he states that his debt to Daniel Jones was so great that without that aid he could not have written the book. He also says the second edition is not much altered from the first. His exercises reflect Jone's intonation curves."

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. 2.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 319.

- ↑ Pike, Kenneth L. (1948). Tone Languages. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 15.

- 1 2 Windsor Lewis, Jack (1973). "English Intonation Studies". Phonetics Department Report. University of Leeds. 4: 75. ERIC ED105744.

- ↑ Asher 1994, p. 221; Collins & Mees 1999, p. 432 citing a letter from F. G. Blandford to H. Palmer written 23 August 1933.

- ↑ Pike 1945, p. 8.

- ↑ Armstrong & Ward 1931, p. 1.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1932). The Phonetics of French: A Practical Handbook. London: Bell.

- ↑ Armstrong 1932, p. 1.

- ↑ The Centre for Information on Language Teaching; The English-Teaching Information Centre of the British Council (1968). A Language-Teaching Bibliography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Armstrong 1932, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ Hedgecock & 1934–1935, p. 163.

- ↑ Armstrong 1932, pp. 131–149.

- ↑ Coustenoble, H. N.; Armstrong, L. E. (1934). Studies in French Intonation. Cambridge: Heffer.

- ↑ Post, Brechtje (2000). Tonal and Phrasal Structures in French Intonation (PDF). LOT International Series. 34. The Hague: Thesus. p. 18. ISBN 978-90-5569-117-3.

- ↑ Leach, Patrick (1988). "French Intonation: Tone or Tune?". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 125. doi:10.1017/S002510030000373X.

- ↑ Post 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ Post 2000, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Coustenoble & Armstrong 1934, p. 3, quoted in Post 2000, p. 8.

- ↑ Hedgecock, F. A. (1934–1935). "[Review of Coustenoble & Armstrong 1934]". Reviews. Modern Languages. 16 (5): 164.

While the object of the book is to study especially the tune of French, that tune is often compared with the one used in similar circumstances in English; so that the book becomes almost a comparative study of French and English intonation.

- ↑ Simpson, W. (1933–1936). "[Review of Coustenoble & Armstrong 1934]". Revue des Langues Romanes. 67: 243–247.

Cet ouvrage est un manuel destiné surtout à l'enseignement en Angleterre où il paraît avoir reçu un accueil favorable.

- ↑ Lloyd James, Arthur (April–June 1936). "[Review of Coustenoble & Armstrong 1934]". kɔ̃trɑ̃dy. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 54: 25.

it iz impɔsibl tu imadʒin ə fulər ɔː mɔː diːteild triːtmənt, ənd ði əbʌndəns əv eksəsaiziz meiks it nɔt ounli ən admrəbl wəːk əv refrəns bət ən eksələnt tiːtʃiŋ manjuəl.

- ↑ Ewert, A. (1936). "Romance Philology, Provençal, French". The Year's Work in Modern Language Studies. 6: 30.

- ↑ Richter, Elise (1938). "Neuerscheinungen zur französischen Linguistik". Neuphilologische Monatsschrift. 9: 166.

Eine vortreffliche Leistung ist das Lehrbuch über den französischen Tonfall.

- ↑ Hall, Jr., Robert A. (1946). "The Phonemic Approach: Its Uses and Value". The Modern Language Journal. 30 (8): 527. JSTOR 318319. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1946.tb04872.x.

- ↑ Leach 1988, p. 126.

- ↑ Collins & Mees 1999, p. 335.

- ↑ Armstrong 1933a, p. 74.

- ↑ Jones 1950, p. 188.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (October–December 1933a). "soʊmɑlɪ" [Somali]. spesimɛn [Spécimens]. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 44: 72–75.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1933). "Somali". In Jones, D.; Camilli, A. Fondamenti di grafia fonetica. Testi. Hertford, UK: Stephen Austin. pp. 19–20.

- See: "nɔt". Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 43: 59. July–September 1933.

nuz adrɛsɔ̃ no rəmɛrsimɑ̃ a trwɑ mɑ̃ːbrə ki ɔ̃t y la bɔ̃te d nu dɔne de nuvɛl vɛrsjɔ̃ de "la biːz e l sɔlɛːj" pur nɔtrə syplemɑ̃ Fondamenti di grafia fonetica; [...] e madmwazɛl L. E. Armstrong [a prepare] la vɛrsjɔ̃ [nuvɛl] ɑ̃ sɔmali.

- See: "nɔt". Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 43: 59. July–September 1933.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1934). "The Phonetic Structure of Somali". Mitteilungen des Seminars für orientalische Sprachen zu Berlin. 37 (Abt. III, Afrikanische Studien): 116–161.

- ↑ Armstrong 1934, p. 116.

- ↑ Andrzejewski 1978, p. 39; Hanghe, Ahmed Artan (1987). "Research Into the Somali Language". Transactions of the Somali Academy of Sciences and Arts/Wargeyska Akademiyada Cimilga & Fanka. Mogadishu. 1: 45. hdl:2307/5625.

- ↑ Armstrong 1933a, p. 72.

- ↑ Jones, Stephen (January–March 1934). "somɑːlɪ ħ ənd ʕ" [Somali ħ and ʕ]. artiklə də fɔ̃. Le Maître Phonétique. 3rd Ser. 45: 8–9.

- ↑ Andrzejewski, B. W. (1978). "The Development of a National Orthography in Somalia and the Modernization of the Somali Language". Horn of Africa. 1 (3): 39–41. hdl:2307/5818.

- ↑ Andrzejewski & 1993–1994, p. 48. "It may be of interest to note that the use of doubled vowels in the Somali national orthography is due to Armstrong's influence. In her work at the International African Institute, based in London, Armstrong and some of her colleagues modified the International Phonetic Alphabet in this way to deal with languages which have vowel length distinctions."

- ↑ Andrzejewski, B. W. (1955). "The Problem Of Vowel Representation In The Isaaq Dialect Of Somali". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 17 (3): 567. JSTOR 609598. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00112467.

- ↑ Andrzejewski 1955, p. 577.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry M. (1981). "Tonal Accent in Somali". Studies in African Linguistics. 12 (2): 170.

- ↑ Armstrong 1934, p. 130.

- ↑ Armstrong 1934, pp. 143–147.

- ↑ Klingenheben, August (1949). "Ist das Somali eine Tonsprache?". Zeitschrift für Phonetik und Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft. 3 (5–6): 289–303. doi:10.1524/stuf.1949.3.16.289.

Hoffmann, Carl (1953). "133. KLINGENHEBEN, August. Is Somali a tone language?". African Abstracts. 4 (1): 46. - ↑ Klingenheben 1949, p. 289. "Mit ihrem Aufsatz 'The Phonetic Structure of Somali' hat uns Lilias Ε. ARMSTRONG eine ausgezeichnete phonetische Studie über die Sprache zweier Somalisprecher geschenkt."

- ↑ Klingenheben 1949, p. 303. "Das Somali gehört also nicht zu den echten Tonsprachen im phonologisch allein zu rechtfertigenden Sinn, sondern zu den Starktonsprachen."

- 1 2 Andrzejewski, B. W. (1956). "Accentual Patterns in Verbal Forms in the Isaaq Dialect of Somali". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 18 (1): 103. JSTOR 610131. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00122232.

- ↑ Andrzejewski, B. W. (1956). "Is Somali a Tone-Language?". In Sinor, Denis. Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Congress of Orientalists. London: Royal Asiatic Society. p. 368.

Somali, in my opinion, is a border-line case between a tone language and a stress language and may require a new classificatory term in the existing classification.

- ↑ Serzisko, F. (2006). "Somali". In Brown, Keith. Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics. 11 (2nd ed.). p. 505. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/02075-7.

- ↑ Puglielli, Annarita (1997). "Somali Phonology". In Kaye, Alan S. Phonologies of Asia and Africa: (Including the Caucasus). 1. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. p. 523.

The vowel system of Somali was first described by Armstrong (1934).

- ↑ Green, Christopher; Morrison, Michelle E.; Adams, Nikki B.; Crabb, Erin Smith; Jones, Evan; Novak, Valerie (2014). "Reference and Pedagogical Resources for 'Standard' Somali". Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography. 15: 2, 8–9. ISSN 1092-9576.

[W]e begin our annotations with Armstrong’s seminal (1934) book on Somali phonetics […] There is also more detail in the description of vowels than in other works.

- ↑ Andrzejewski, B. W. (1956). "Grammatical Introduction". Ħikmad Soomaali. By Galaal, Muuse Ħa̧aji Ismaaʿiil. London: Oxford University Press. p. 5. hdl:2307/2059.

Frontness, or its absence, extends over whole words or even groups of words, i.e. whole words or groups of words have vowels belonging to the same series. Armstrong, who was the first to discover this fact, refers to it as Vowel Harmony in her article.

See also Andrzejewski 1955, p. 567. - ↑ Moreno, Martino Mario (1955). Il somalo della Somalia: Grammatica e testi del Benadir, Darod e Dighil. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato. pp. 5, 13. hdl:2307/1509.

[L]e leggi dell'armonia vocalica, così ben indagata da Lilias E. Armstrong […] Lilias E. Armstrong ha studiato con molta accuratezza l'armonia vocalica in isāq.

- ↑ Abraham, R. C. (1951). Introduction. The Principles of Somali. By Warsama, Solomon; Abraham, R. C.

I should like to say how closely I am in agreement with the conclusions reached in Somali phonetics by the late Lilias Armstrong; apart from some slight misunderstandings due to lack of knowledge of the language, there are very few points where I disagree with her — my own conclusions were arrived at independently, and I was not aware of her work until one of my students called my attention.

Quoted in Saeed 1992, p. 112. - ↑ Vycichl, Werner (1956). "Zur Tonologie des Somali: Zum Verhältnis zwischen musikalischem Ton und dynamischem Akzent in afrikanischen Sprachen und zur Bildung des Femininums im Somali". Rivista degli studi orientali. 31 (4): 227. JSTOR 41864402.

Wie dem immer auch sei, die Studie von L. E. Armstrong, die sich auf Gesetzmässigkeiten gründet (und keine Phantasie wiedergibt), eröffnet ein neues Kapitel der Afrikanistik, das auch die Ägyptologie interessieren wird.

- ↑ Saeed, John Ibrahim (1992). "R. C. Abraham and Somali Grammar: Tone, Derivational Morphology and Information Structure". In Jaggar, Philip J. Papers in Honour of R. C. Abraham (1890–1963). African Languages and Cultures, Supplement. 1. London: SOAS. p. 112. JSTOR 586681. hdl:2307/2162.

- ↑ Orwin, Martin (1996). "A Moraic Model of the Prosodic Phonology of Somali". In Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. Voice and Power: The Culture of Language in North-East Africa. Essays in Honour of B. W. Andrzejewski. African Languages and Cultures, Supplement. 3. London: SOAS. p. 51. JSTOR 586653. doi:10.4324/9780203985397. hdl:2307/2169.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1933b). "Some Notes on Kikuyu". Practical Phonetics for Students of African Languages. By Westermann, D.; Ward, Ida C. London: International African Institute. pp. 213–216.

- ↑ Armstrong 1933b, p. 214.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1933). "Ganda". Practical Phonetics for Students of African Languages. By Westermann, D.; Ward, Ida C. London: International African Institute. pp. 188–197.

- ↑ Armstrong, L. E. (1940). The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu. London: International African Institute.

- 1 2 Jones, Daniel (1940). Preface. The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu. By Armstrong, Lilias. E. London: International Africa Institute. pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Berman, Bruce (1996). "Ethnography as Politics, Politics as Ethnography: Kenyatta, Malinowski, and the Making of Facing Mount Kenya". Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines. 30 (3): 313–344. JSTOR 485804.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, pp. xvi, 30–39.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1917). "Analysis of the Mechanism of Speech". Nature. 99 (2484): 285–287. doi:10.1038/099285a0; Collins & Mees 1999, pp. 245–252, discussing Jones 1922, pp. 168–182.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, pp. 354–355.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 31.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 36.

- ↑ International Institute of African Languages and Cultures (1927). Practical Orthography of African Languages. London. pp. 4–5.

ʋ for "bi-labial v", the middle and South German sound of w, the Ewe sound in ʋu (boat), ʋɔ (python), which words have to be distinguished from vu (to tear), vɔ (to be finished).

- ↑ Passy 1927, p. 14. "(5) i desid də rɑ̃plase le siɲ ꜰ, ʋ par ɸ, β. lə siɲ ʋ səra dezɔrmɛ dispɔniblə pur rəprezɑ̃te la kɔ̃sɔn labjo-dɑ̃tal nɔ̃-frikatiːv tɛl k ɛl egzistə dɑ̃ sɛrtɛn lɑ̃ːg ɛ̃djɛn e ɑ̃ hɔlɑ̃dɛ. (puːr 12, kɔ̃ːtr 2, nɔ̃ vɔtɑ̃ 2.)"

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 354.

- ↑ Westermann, D.; Ward, Ida C. (1933). Practical Phonetics for Students of African Languages. Oxford University Press: International African Institute. p. 80.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 32.

- ↑ Bennett, Patrick R. (1986). "Suggestions for the Transcription of Seven-Vowel Bantu Languages". Anthropological Linguistics. 28 (2): 133–134. JSTOR 30028404.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, pp. 9, 38, 354.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 1.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 9.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, p. 1 citing IIALC 1927, p. 5.

- ↑ Tucker, A. N. (1949). "Sotho-Nguni Orthography and Tone-Marking". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 13 (1): 201–204. JSTOR 609073. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00081957.

- ↑ Githiora, Chege (2004). "Gĩkũyũ Orthography: Past and Future Horizons". In Githiora, Chege; Littlefield, Heather; Manfredi, Victor. Kinyĩra Njĩra! Step Firmly on the Pathway!. Trends in African Linguistics. 6. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Armstrong 1940, pp. 39, 354–355.

- ↑ Tucker, A. N. (1971). "Orthographic Systems and Conventions in Sub-Saharan Africa". In Sebeok, Thomas A. Linguistics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Current Trends in Linguistics. 7. The Hague: Mouton. p. 631.

- ↑ Englebretson, Robert, ed. (2015). "Orthography". A Basic Sketch Grammar of Gĩkũyũ. Rice Working Papers in Linguistics. 6. p. xi.

- 1 2 Armstrong 1940, p. xviii.

- ↑ Philippson, Gérald (1991). Ton et accent dans les langues bantu d'Afrique Orientale: Étude comparative typologique et diachronique (PDF) (Thesis). Université Paris V. p. 56.

Le premier ouvrage à décrire de façon approfondie le système tonal d'une langue bantu d'Afrique orientale est celui de L.E. Armstrong sur le kikuyu.