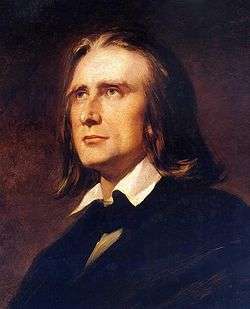

Life of Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (October 22, 1811 – July 31, 1886) was a prolific 19th-century Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor, music teacher, arranger, organist, philanthropist, author, nationalist and a Franciscan tertiary. Liszt is widely considered to be the greatest pianist of all time.[1]

Origin

Franz Liszt was born on October 22, 1811, in the village of Raiding (Hungarian: Doborján) in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Habsburg Empire (and since 1920 also part of Austria), in Sopron County (German: Ödenburg). Liszt was the only child of Adam Liszt and Anna Lager. Anna Lager was half Austrian and half Bavarian. Liszt's god-parents were Magyars: Franciscus Zambothy and Julianna Szalay. Liszt was baptized Franciscus, the Latin version of the name Franz or Ferenc. The main language in that region was German, while only a small minority could speak and understand Hungarian. For official purposes Latin was used. Children had only had lessons in Hungarian since 1835.[2] Liszt himself became fluent in German, French and Italian. He also had some knowledge of English, but his knowledge of Hungarian was very poor. In the early 1870s, Liszt also tried to learn it, but after some lessons he gave up.

The issue of Liszt's nationality has triggered a few interpretations.[3] The question is considered by some to be controversial to this day, since important sources are missing. According to the mainstream literature about Liszt, his great grandfather Sebastian List was a German who came to Hungary in the early 18th century. This is according to Walker, but other sources mention Sebestyén born in Rajka, Sopron county, Kingdom of Hungary, about 1703.[4] Since in Hungary the nationality of a child was inherited from the father's side, Liszt's grandfather Georg List and Liszt's father Adam List would have been Germans too if Sebastian would have immigrated from Austria. On the other hand, the theory of Sebastian List's German origin is an assumption without sufficient proof in sources. During the 1930s, Ernő Békefi searched in Hungarian archives for Sebastian List's birth certificate. Since he could not find it, he presumed that Sebastian List must in his youth have come to Hungary.[5] However, Sebastian List's birth certificate has not been found in German or Austrian archives either. Since during the 18th century many materials in Hungarian archives were destroyed by the Ottoman Turks, it can be imagined that this was the reason Békefi could not find Sebastian List's birth certificate – Sebastian List might therefore have been born in Hungary. According to Lina Ramann, Sebestyens father was an officer of lower rank at a Hussar-regiment and died at Rajka.[6]

In the vast majority of Liszt literature he is regarded as either Hungarian or German. Many authors, among them Émile Haraszti and Béla Bartók, regarded the character of Liszt's music as mainly French.[7] Liszt, since 1838 at least, insisted that he was Hungarian. Liszt and his father Adam only ever had Hungarian passports. Furthermore, his children bore Hungarian citizenship as well. In an 1845 letter to the abbot Lamennais, Liszt wrote: "My children bear their father's nationality. Whether they like it or not they are Hungarians". One also has to note that the name "Liszt" means "flour" in Hungarian.

There might be a family connection to the baronial Listi family of László Liszti who lost all their fortunes but before had a castle at Köpcsény (Kittsee) in the area where the composer's family actually lived. Liszt himself tried to prove a relation to this family. Lina Ramann wrote about this probable family connection in her biography.[6] The first known Liszt (Listi) was a certain Kristóf from Transylvania, Kingdom of Hungary. He had three sons: Sebestyén, born in Nagyszeben (Sibiu or Herrmanstadt)), András and János. They were ennobled in 1554. János was baron of Köpcsény and died in Prague in 1577. He married Lucretia Oláh and became bishop of Győr. They had children: János, István and Ágnes.[8] Ferenc Liszti (baron of Köpcsény was an advisor to Gabriel Bethlen. He had a son László Liszti (born 1628 in Nagyszeben, executed 1662 in Vienna) who was a poet.[9] There was also one Sámuel List, born in Késmárk who became a medical doctor at the university of Nagyszombat in 1777.[8] Other Liszts, with the spelling List are described by Hungarian author István Csekey in his Liszt biography. These lived in Sopron, western Hungary, and some are already from the beginning of the 15th century. List means treeleaf in Croatian and Slovakian, which is one of the reasons to Slavic claims. Croatia and what later became Slovakia was up to 1920 parts of the Hungarian Kingdom. Liszt means flour in Hungarian.

The earliest form of his name appears to be Listhius, which Kuhac claims with some plausibility as Slavonic (nase gore list). But as early as 1747 the Magyarised form appears in the person of Canon Johann Liszt; and there can be little doubt that by the time of the pianist's birth the family had become thoroughly Hungarian. There are, of course, many Hungarian families in which Magyar and Slavonic strains are united, and in the music of Liszt the Magyar element unquestionably predominates.[10] The earliest spelling of "Liszt" was a Stephani (István) Liszt by Miklós Oláh (Nicolaus Olahus).[11]

The German Lina Ramann, who wrote the first biography, credits Liszt as an ethnical Hungarian.[6] Another biographer, the German national-socialist Peter Raabe, wrote that Liszts German origin could not be proved.[12] Liszts compatriot composer Béla Bartók said that according to the prevailing documents it was impossible to tell if Liszt's origin was German, slav or magyar,[13] The Croatian Kuhac claimed plausible Slavonic (i.e. Slavic from Slavonia, then in the Kingdom of Hungary) origin.[10] Sir William Henry Hadow wrote that Liszt was an ethnical Hungarian.[10] In Walker' s Liszt family-tree there are also Germanized Magyar names (Schandor instead of Sándor) as there are Germanized Slavic ones (Schlesak instead of Slezak)[14] to add to the general confusion. The German-Magyar battle over Liszt started first after WW1, when Váralja/Burgenland became Austrian. During the national-socialist era (1933–1945) most German biographers claimed Liszt to be German. Liszt considered himself Hungarian, wrote in 1873: "It must surely be conceded to me that, regardless of my lamentable ignorance of the Hungarian language, I remain from birth to the grave, in heart and mind, a Magyar."[15] Liszt also wrote: "I too belong to that strong and ancient race, I too am a son of that original an undaunted nation..."[16]

Early life

Every attempt to describe Liszt's development during his childhood and early youth has met with the difficulties of terribly sparse information. It had been Adam Liszt's own dream to become a musician. He played piano, violin, cello, and guitar, was in the services of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy and knew Joseph Haydn, Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Ludwig van Beethoven personally. Franz Liszt, as a mature artist, frequently said himself that the most important musical impressions of his childhood had been the playing of Gypsy artists. However, the actual repertoire that he studied as a boy at the piano was different. According to Adam Liszt's letter to Prince Esterházy of April 13, 1820, he had bought 1,100 "Bogen", i.e. 8,800 pages, of music of the best masters. During the previous 22 months, his son already had worked through the complete works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Clementi, Hummel, Cramer, and further composers besides.[17]

In October 1820, at the old casino of Ödenburg, he took part in a concert of the violinist (alleged) Baron von Praun, who was a child prodigy himself. In the second part of the concert, Liszt played a concerto in E flat major by Ferdinand Ries with much success and an improvisation of his own. In November 1820 Adam Liszt took up an even better opportunity to present his son's playing to the public. In Pressburg, the Diet met for the first time after a break of 13 years. On November 26, at Count Michael Esterházy's palace in Pressburg, Liszt performed for an audience of aristocrats and members of the society. A group of magnates undertook to pay Liszt an annual sum of 600 Austro-Hungarian Gulden for six years so that he could study abroad.

In Vienna, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny, who in his own youth had been Beethoven's student. Czerny, according to his "Lebenserinnerungen" (Memoires), was struck by the boy's talent but found that the boy had no knowledge of proper fingerings and that his playing style was very chaotic.[17] Since July 1822, Liszt was also studying composition with Antonio Salieri. According to Salieri's letter to Prince Esterházy of August 25, 1822, he had until then introduced his pupil to some elements of music theory. Earnest lessons in composition were to follow later.[18] As the child prodigy's admirers soon began idolizing him as a new Mozart or Beethoven, Salieri had his work cut out for him. Allusions to this problem can be found in Schilling's Franz Liszt.

Very soon Liszt was heard in private circles. His public debut in Vienna was on December 1, 1822, at a concert at the Landständischer Saal. Liszt played Hummel's Concerto in A minor as well as an improvisation on an air from Rossini's opera Zelmira and the Allegretto of Beethoven's 7th Symphony. On April 13, 1823, he gave a famous concert at the Kleiner Redoutensaal. This time he played Hummel's Concerto in B minor, variations by Moscheles, and an own improvisation. According to legend, he impressed Beethoven to such an extent that he congratulated Liszt on the stage, kissing him on the forehead and giving him enthusiastic praise.

In spring 1823, when the one year's leave of absence came to an end, Adam Liszt asked Prince Esterházy in vain for two more years. Adam Liszt therefore took his leave of the Prince's services. At the end of April 1823, the family for the last time returned to Hungary. At the end of May 1823, the family returned to Vienna.

The child prodigy

On September 20, 1823, the Liszt family left Vienna for Paris. To support himself and his parents, Liszt gave concerts in Munich, Augsburg, Stuttgart and Strasbourg. In Miesich he was regarded as an equal to the boy Mozart.[19] On December 11, 1823, the family arrived in Paris. The next day, Adam Liszt together with his son went to the Conservatoire, hoping the child prodigy would be accepted as a student. But Cherubini, the director, told them that according to a new rule only the French were allowed to take part in piano class. Consequentially, Adam Liszt, who had very despotic manners, now became his son's only piano teacher. He had his son practise scales and études with a metronome[20] and also play a number of fugues by J. S. Bach every day, transposing them into different keys.[21]

Liszt learned French quickly and it became his main language. He made the acquaintance of the piano manufacturer Sébastien Érard, pioneer of the "double-escapement" system of piano mechanics.[22] Liszt played in private circles and gave concerts on March 7 and April 12, 1824, at the Theâtre Italiènne, quickly augmenting his popularity. He was well known in Paris as petit Liszt ("little Liszt"). In 1824, 1825 and 1827, together with his father, he visited England, where he was known as "Master Liszt". His share of the admissions was large enough for his father to invest a sum of 60,000 Francs[23] in bonds of his former employer Prince Esterházy. The principal was repaid in 1866 when Liszt's mother died. She had until then received the interest payments.[24]

Since 1824, Liszt studied composition with Anton Reicha and Ferdinando Paer. From Adam Liszt's letters it is known that his son had composed several concertos, sonatas, works of chamber music, and much more. While nearly all of those works are lost, some piano works of 1824 were published. These pieces were written in the common style of the contemporary brilliant Viennese school. He had taken works of his former master Czerny as a model, which Liszt's later virtuoso rivals Sigismond Thalberg and Theodor Döhler would also emulate. The response to these early works was disheartening. In spring 1824, with Paer's help, Liszt started composing an opera Don Sanche, ou Le château de l'amour ("Don Sanche, or The Castle of Love"). Conducted by Rodolphe Kreutzer, with Adolphe Nourrit as Don Sanche, the opera premiered on October 17, 1825 at the Académie royale de Musique, but without success. Liszt afterwards felt drawn in a different direction, he became increasingly distant from the idea of promoting himself musically and became more absorbed with personal religious discovery. However, he was forced by his father to continue giving concerts.[25] In 1826 in Marseille he started composing original etudes. They were projected as 48 pieces, but only 12 pieces were realized and published as his Opus 6.

In summer 1827, Liszt fell ill.[26] Adam Liszt went with his son to Boulogne-sur-Mer, a spa town on the English Channel. While Liszt himself was recovering, his father fell ill with typhus. On August 28, 1827, Adam Liszt died. Liszt composed a short funeral march which might have carried a double meaning. Together with his father, the concertizing child prodigy had died. Adam Liszt was buried in Boulogne. Liszt never visited his father's grave.

In later years, Liszt himself always took a skeptical point of view regarding his career as child prodigy. While he had earned much money and gained a prominent name, his general education had had no chance of development.[27] He made up for this lack by intense reading. Starting in the early 1830s, he read voraciously, and by the time of his death in 1886 he had acquired many thousands of books. Regarding his compositional oeuvre as child prodigy, he wrote to Lina Ramann in March 1880 that nothing had come of it because there was nothing to it. For young as well as for old composers, he felt it was best if the manuscripts were lost.[28]

Adolescence in Paris

Artistic development

After his father's death Liszt returned to Paris. For the next five years he was to live with his mother in a small apartment at 7 Rue Montholon. In 1831 they moved to 61 Rue de Provence. At the end of 1833 Liszt rented his own apartment which he called "Ratzenloch".[29] To earn money, Liszt gave lessons in piano playing and composition, privately as well as at a private school for young ladies at 43 Rue de Clichy, run by one Madame Alix. On October 23, 1828, the Corsair erroneously reported that Liszt had died. But a correction appeared in the same paper three days later: a note from Madame Alix said that he had not ceased teaching at her school and was in good health.[30]

On occasion Liszt performed at private soirées typically organized by Rossini, who would invite other artists as well. At the designated time, they all entered their host's mansion via the back door. In the salon, they silently assembled around the piano. They would perform their pieces in turn. After the host had politely thanked them, they would leave. Rossini would receive the money the next day to distribute among the artists.[31] Liszt also took part in concerts by other artists. At the end of December 1830 or at the beginning of January 1831, Liszt left Paris, travelling to Geneva. The voyage led to severe problems in his private life.[32] For those reasons there was a gap of nearly two years in Liszt's concert activities. It was not until January 28, 1832, that he accepted an invitation to a charity concert in Rouen.[33] On April 2, 1832, he performed at a concert in Paris again.

During winter 1831–32, Liszt made the acquaintance of Felix Mendelssohn and Frédéric Chopin. Both of them arrived in Paris with a suitcase full of masterworks. In comparison with this, Liszt —neglecting his works as child prodigy— had not much more to offer than an oeuvre of a single piece, his Bride-fantasy. Their impression of Liszt is known from their letters. Chopin, in a letter to Titus Woyciechowski of December 12, 1831, wrote that "all Parisian pianists, including Liszt, were zeros in comparison with Kalkbrenner".[34] Mendelssohn, in a letter to his sister Fanny of December 28, 1831, wrote that "Liszt was the most dilettantic of all dilettantes. He played everything from memory, but with the wrong harmonies".[35]

Important influences on Liszt also came from the sect of the religiously-oriented Père Enfantin faction of the Saint-Simonists. As part of their ideology, contemporary forms of marriage were regarded as prison for women and in this sense as a kind of crime.[36] In the beginning of January 1832 they distributed a flyer according to which all artists should take part in the new religion. They were to create better music than Beethoven and Rossini.[37] On January 11, 1832, Liszt —himself a follower of the Père Enfantin[38]— told his student Valerie Boissier and her mother Auguste that he would cease giving lessons to concentrate all of his forces on his development as artist.[39]

In spite of his announcement, Liszt continued giving lessons. Then, after attending an April 20, 1832 charity concert, for the victims of a Parisian cholera epidemic, by Niccolò Paganini[40] Liszt became determined to become as great a virtuoso on the piano as Paganini was on the violin.[41] According to a letter to Pierre Wolff of May 2, 1832,[42] he was practicing scales, thirds, sixths, octaves, tremolos, repetitions of notes, cadenzas, etc. up to five hours a day. However, by the time the letter was delivered, Liszt was no longer practising that much. According to a second part, written on May 8, he had left Paris, following an invitation by one family Reiset for a vacation in Ecoutebœuf, a small place near Rouen.[43]

In Ecoutebœuf, Liszt started composing his "Grande Fantaisie de Bravoure sur La Clochette de Paganini" ("Grand Bravura Fantasy on Paganini's La Campanella") on a melody from the rondo finale of Paganini's second violin concerto. The early version of the Clochette-fantasy was not yet completed because Liszt fell ill in Ecoutebœuf.[44] When on November 5, 1834, at a concert of Berlioz, he for the first time played the fantasy, it was a complete fiasco and taken as new proof that Liszt had no talent for composition at all.[45] A shorter piece using the same melody as well as a melody from the finale of Paganini's first concerto was included in the 1838–39 Etudes d'exécution transcendante d'après Paganini ("Studies of Transcendental Execution after Paganini").

In 1833, Liszt began seeing Marie d'Agoult. In addition to this, at the end of April 1834 he made the acquaintance of Felicité de Lamennais. Under the influence of both, Liszt's creative output exploded. Until May 1835 he composed at least half a dozen works for piano and orchestra, a duo-sonata for piano and violin on a Mazurka by Chopin, a duo for two pianos on two of Mendelssohn's "Lieder ohne Worte", and much more. All this found a very abrupt end, after Liszt on June 1, 1835, left Paris, travelling to Basel. Most of the works he had composed from summer 1832 to May 1835 were neither published nor performed. In a "Baccalaureus-letter" to George Sand, published in the Revue et Gazette musicale of February 12, 1837, Liszt vowed to consign them to the fire.

Caroline de Saint-Cricq

As an integral part of the usual Liszt biography, a love affair with his pupil Caroline de Saint-Cricq must be mentioned, although documented evidence for this has, until 2011, been less than meager. Traditionally Caroline has been described as nothing short of an angel come down to earth,[46] without worldly desires of whatsoever kind. Besides, she was very beautiful and very rich. Liszt, who had not the least interest in those qualities, became her piano teacher in spring 1828 when he was 16 and she was 17. While talking exclusively of holy things, they quickly fell in love. Supported by Caroline's mother, they wanted to marry. Shortly afterwards, on June 30, 1828, the mother died. Caroline's father, French Minister of Commerce in the government of Charles X, then acted as antagonist, showing Liszt the door. Caroline fell ill, and Liszt suffered a nervous breakdown. At age 20, i.e., in March 1831, Caroline married one Bertrand d'Artigaux. Together with her husband, she moved to Pau in southern France. Until recently, sources on Caroline have been absent or contained idealized romantic data.[47] Extensive details about Caroline de Saint-Cricq, her birth, life, family, and her love affair with Liszt have been published by the British Liszt Society Journal in 2011 [48] as well as on internet [49]

Adèle de Laprunarède

A further love affair, as reported by Liszt's biographers, sounds even more adventurous. Per Alan Walker, after the revolution of 1830 a total change of Liszt's personality must have occurred. His nervous breakdown was forgotten, his holy ideas were discarded, and he was now hungry for whatever experiences life had to offer.[50] With Adèle de Laprunarède,[51] very beautiful and very rich, although married, he enjoyed his first long love affair. Surrounded by snow and ice, with mountain roads impassable, they were marooned on Marlioz Castle in the Savoy for the whole winter of 1832/33.[52] However, the impression created by Liszt's own comment in one of his early letters to Marie d'Agoult is again different: "I've been nothing but a cowardly and miserable poltroon for Adèle."[53] In addition, there was still another lady, also very beautiful, with whom Liszt traveled to the Savoyen Alps. Her name was "Mlle. de Barré".[54] Besides, Walker mentions ladies "Madame D..." and "Charlotte Laborie", who both wanted to get Liszt married.[52] More reliable sources indicate that "Madame D..." was Madame Didier, a very close friend of Liszt's mother. She also lived at 7 Rue Montholon and wanted to marry her daughter Euphémie to Liszt.[55]

Marie d'Agoult

In summer 1832, while Liszt was composing his Clochette-fantasy, he was also making plans for other works. But he found no time to carry them out. At the end of August 1832 he went to Bourges, where his former student Rose Petit was getting married. On October 6 he returned to Paris.[56] During the whole winter of 1832–33, i.e., until the end of April 1833, he was involved in many social events, often returning home in the early morning.[57] For this reason only a single new work, a free transcription of Schubert's song "Die Rose", was published.[58] On December 9, 1832, Liszt attended a concert at which Berlioz' Symphonie fantastique and —with brilliant success— for the first time the sequel Lélio ou le Retour à la Vie ("Lélio or the Return to Life") were performed. The concert was also attended by Marie d'Agoult.[59]

Liszt was feeling more and more averse to the social life;[60] Marie d'Agoult's situation was similar. In the winter of 1831/32, with her husband Charles and their daughters Claire and Louise, she travelled to Geneva, where the married couple experienced a crisis. In addition in January 1832, one of Marie d'Agoult's cousins committed suicide.[61] Marie d'Agoult herself had ideas of suicide and was attended to at the sanatorium of one Dr. Coindet in Geneva; her husband took their daughters back with him to Paris. In April 1832, Marie d'Agoult's half-sister Auguste Ehrmann committed suicide.[62] After Marie d'Agoult's own return to Paris, she started in December 1832 to rejoin the social life but found the usual customs stupid and annoying. She then decided to buy an estate with a castle at Croissy, a small village near Paris.[63] The contract of sale was concluded on April 18, 1833,[64] for a sum of more than 300,000 Francs.

According to Marie d'Agoult's Memoirs, written from a distance of more than 30 years,[68] she had made Liszt's acquaintance at the end of 1833 at a soiree given by a Marquise le Vayer.[69] But the Marquise had already died on February 1, 1833,[70] and Marie d'Agoult's correspondence with Liszt includes letters from spring 1833. The question of the precise beginning of their acquaintance is therefore open. Liszt performed at soirees of the same social circles which were frequented by Marie d'Agoult. An example is Count Rudolph Apponyi, Austrian ambassador in Paris, who arranged private concerts at his home on every Sunday. His wife was a close friend of Marie d'Agoult,[71] who on December 23, 1832, visited the Apponyis.[72] One week later, on December 30, Liszt performed at the same place.[73] Liszt and Marie d'Agoult therefore might have met already at earlier occasions. However, Liszt himself, in a letter of July 17, 1834, gave a hint pointing back to a date 18 months prior.[74] Hence January 1833 might be regarded as their starting point.

In winter 1833–34 Liszt rented the "Ratzenloch". Several times Marie d'Agoult visited him disguised as "Comte de la B...".[75] Also, Liszt visited her at Croissy. He made friends with her daughters who gave him the nickname "Bon Vieux" ("Good Old One").[76] Since April 28, 1834, Liszt was in Paris alone again, while Marie d'Agoult had retired to Croissy.[77] In May 1834, he had a dispute with Madame Laborie. She presumed that he was still in love with Adèle de Laprunarède and tried to force him to give her Adèles letters.[78] On May 16 Liszt left Paris, following an invitation by one Madame Haineville to Castle Carentonne near Bernay in Normandy. While he was in Carentonne Marie d'Agoult found some of his old letters to Euphémie Didier, suspecting they were written to Adèle and Liszt had become engaged with her.[79]

Returning from Carentonne, Liszt arrived in Paris on June 22, 1834.[80] A couple of days later Marie d'Agoult left, travelling to Mortier,[81] an estate of her mother where she stayed for two months. As of summer 1834 it was clear that Liszt and Marie d'Agoult were a couple. But their affaire had a colour of a very particular kind. Liszt's letters of spring and summer 1834 are full of complaints about his illness and depression. Yet even in letters of July 1834 he described Marie d'Agoult as a woman whom he desired, after whom he always had to run but without ever reaching her.[82]

George Sand

In autumn and winter 1834–35, Liszt made the acquaintance of George Sand. He had in the Revue des Deux Mondes of May 15, 1834, read her first Lettre d'un voyageur on her impressions of Italy, which he found magnificent.[83] In a letter to Marie d'Agoult of August 25, 1834, he wrote, he had two days earlier met Alfred de Musset. Musset had told him much about George Sand. Liszt had asked Musset to gain him an introduction when Musset would next meet George Sand.[84]

At the time – January 1835 – George Sand and Musset were getting along.[85] However, new problems arose after she had met Liszt: rumours of Liszt and George Sand having an intimate affair with each other. Later that same month, in order to defend herself George Sand tried to get Liszt to vouch for her innocence, but he had disappeared and two letters to him were not answered.[86] In letters to the Abbé de Lamennais and to Marie d'Agoult of January 14, Liszt had announced that he would leave Paris for a voyage the following day.[87] Afterwards, for the whole period of January 15 until the end of February 1835, he seemed to have vanished from the face of the earth.[88]

Liszt in Geneva

From July 28, 1835, Liszt and Marie d'Agoult lived in an apartment of the building on the corner of Rue Tabazan and Rue des Belles-Filles, now 22 Rue Etienne Dumont, where Liszt's first child, Blandine, was born.[89] He also taught at the Conservatoire de musique de Genève.

Concert tours

Problematic beginning

In autumn 1837 Liszt's situation was precarious. He had on September 6, together with Marie d'Agoult, arrived in Bellagio and had there started composing. By October 22, 1837, his 12 Grandes Etudes were complete. Liszt had also commenced his Impressions et poésies which were destined to be published one year later as part of the Album d'un voyageur. Unfortunately his reputation as a composer languished at a low level. It was difficult for Liszt to find a publisher willing to take his works. Liszt contacted the publishers Mori in London and Haslinger in Vienna. The answers which he received from both were nearly identical. They requested that Liszt first travel to London and Vienna and play his works in concerts there. In addition, Liszt received a letter from his former teacher Czerny who also suggested a voyage for concerts to Vienna. Until the end of 1837 Liszt's arrival in Vienna was daily expected, but he was tied down in Italy, standing by the very pregnant Marie d'Agoult. On December 24 their second daughter Cosima was born.

In the beginning of April 1838, Liszt and Marie d'Agoult were now living in Venice, and he travelled for concerts to Vienna, taking a flood in Hungary as his chance. When Liszt left Vienna at the end of May 1838, he had to promise that he would return in September for concerts in Vienna and also in Hungary. In order to make it possible, he agreed with Marie d'Agoult that they would together travel along the Danube to Constantinople. In spite of preparations, Liszt's plan did not work. On May 9, 1839, Liszt's son Daniel was born in Rome, and he started his virtuoso career as the father of three children.

Trieste, Vienna, Leipzig

On October 18, 1839, Liszt accompanied Marie d'Agoult to Livorno, from where she and her daughters Blandine and Cosima traveled via Genoa, Marseille and Lyon to Paris, arriving on November 3. Daniel had been left behind in Italy, where the painter Henri Lehmann took care of him.[90] Liszt first travelled to Venice, then to Trieste, where he gave concerts on November 5 and 11. On November 19, 1839, Liszt gave a first concert in Vienna. He was afterwards ill for about a week. From November 27, Liszt gave additional concerts in Vienna. They were huge successes. On December 5, 1839, Liszt headlined the bill, playing for the first time his Sonnambula-fantasy, and at a "Concert Spirituel" at which he played Beethoven's Concerto in C Minor. He had learnt the concerto the previous night. Liszt also took part in concerts of other artists, among them Madame Camilla Pleyel with whom he had had a love affair several years before. They played a brilliant fantasy for four hands on Rossini's "Wilhelm Tell" by Herz.

On February 1, 1840, Liszt returned to Vienna, where he gave further concerts. During the first half of March 1840, he played in Prague. Although until now the success of Liszt's concerts had been sensational, his successes decreased after he left the city, travelling to Dresden and Leipzig. Especially in Leipzig, Liszt encountered strong hostility. Schumann, who had met Liszt in Dresden, wrote reviews praising Liszt's concerts. Mendelssohn also tried to save the situation. To help Liszt, he organized a concert on March 30 in the Gewandhaus. Mendelssohn participated in the concert by playing a J. S. Bach concerto for three keyboards alongside Liszt and Ferdinand Hiller. Yet, even with the apparent brilliance of Liszt's performance, when he left Leipzig he still had many enemies there.

Paris and a first tour of Britain

In the beginning of April 1840, Liszt travelled via Metz to Paris. In letters to Marie d'Agoult he had imagined his return as the triumphant beginning of a new period of his life. As a point of honour, he would give a series of concerts in Paris, earning at least 20,000 Francs from them. But after his arrival Liszt learnt that his successes in Vienna, Pest and Prague counted as nearly nothing in Paris.[91] The "sabre of honour" brought less pleasure than pain to him. It evoked a flood of caricatures, sarcastic comments and polemical attacks in the press.[92] Berlioz wrote in an article in the Journal des Debates, "We let Mozart and Beethoven starve to death, while giving a sabre of honour to Mr. Liszt."[93]

Instead of a series of concerts, Liszt gave only a single matinee on April 20 at the Salons Erard. Besides he took part in a concert of ecclesiastical music, given by the Princess Belgiojoso. The matinee had had the character of a private concert, since Liszt himself had invited his audience. This brought his total earnings in Paris to zero. Even worse, reviewers compared Liszt to his rival Thalberg, who had arrived in Paris a couple of weeks before Liszt. Although Thalberg gave no concert, he was nevertheless regarded as the leading piano virtuoso of the time. In contrast to Liszt, Thalberg was also praised as composer of genius.[94]

In the beginning of May 1840 Liszt went to London. He had hoped that he could in London gain a victory over Thalberg by earning more money than his rival, but the financial result of his concerts was disappointing. On June 7, 1840, Marie d'Agoult joined Liszt in England. She stayed in Richmond while Liszt was occupied with concerts in London. On June 20, an éclat occurred.

On August 15, 1840, in Rotterdam, Liszt and Marie d'Agoult had to separate. While Marie d'Agoult returned to Paris, Liszt travelled to England. As a member of the troupe of Lewis Henry Lavenu he made a tour of England consisting of about 50 concerts covering the length and breadth of the country. Lavenu was the stepson of publisher and violinist Nicolas Mori. Accompanying them on the tour were Lavenu's half-brother Frank Mori, a pupil of Sigismond Thalberg, two singers, Louisa Bassano and Mlle. de Varny, and John Orlando Parry, a musician, singer and entertainer (who vividly recorded the tour in his diary[95]). They started on August 17, giving concerts in Chichester and Portsmouth. Six weeks later, the tour ended with concerts on September 25 and 26 in Brighton. The success was only moderate. Lavenu came out with a net loss of 5,000–6,000 Francs,[96] but he negotiated a second tour with Liszt for winter 1840/41.

Fontainebleau, Hamburg, second British tour

Following Liszt's first tour in England he returned to Paris to meet Marie d'Agoult. They traveled to Fontainebleau for a fortnight's holiday, enjoying a happy respite from their cares. Later they would both claim not to have considered marriage. But it is known from their letters that during their stay in Fontainebleau they became engaged. Marie d'Agoult, still wedded to her husband Charles, hoped she could follow the recent example of Princess Belgiojoso. The Princess, after several years of being separated from her husband, had just been divorced.[97] Liszt might have thought of still another example. He admired Schumann, who had on September 12, 1840, married Clara Wieck.

Liszt planned to give concerts from Fontainebleau to Hamburg. After, he would go to Berlin. During the winter he would play in Great Britain, travelling once again with Lavenu's troupe. In January 1841 he would return via Brussels to Paris. Together with Robert and Clara Schumann, he would then play in Saint Petersburg and Moscow, concluding in May and June 1841 with concerts in London. After this last stay, his touring days would be over. Together with Marie d'Agoult he would travel via Geneva to Italy, where a stay with a long rest would follow. In order to avoid further strife, Liszt had promised to take Marie d'Agoult's counsel in all important matters.

Liszt left on October 19. He first returned to Paris, visiting the music publishers Bernard Latte and Maurice Schlesinger. At Schlesinger's office he met by chance his later son-in-law Richard Wagner. It was a fleeting first encounter that left no traces. From Paris, Liszt travelled to Hamburg, arriving on October 26. His first concert was on October 28. The program included some pieces of vocal music, but it turned out that the singers were not allowed to take part in the concert. In a short speech Liszt announced that he would play more solo pieces instead. His second concert, on October 31, was a greater success. On November 2 he took part in a concert of his pupil Hermann Cohen. While Liszt had planned to leave on November 4 for Berlin, he took his chance in Hamburg, giving an additional "last concert" on November 6.[98] On that day he received a letter by Lavenu according to which he was expected in London on November 22. Since this did not leave enough time for traveling to Berlin and performing at concerts there, he gave another "farewell concert" in Hamburg on November 10.

A becalmed Channel slowed him down, and it was not until November 23 that Liszt arrived in Dover. Yet another delay occurred when Liszt missed his train to London. Lavenu's troupe had on November 23 already given a first concert in Reading. Since Liszt, announced as a superstar, was absent, most of the 140 people in the audience had left in anger. A concert in Newbury, also announced for November 23, was therefore cancelled. Lavenu travelled to London, where he met Liszt on November 24. That evening, Liszt arrived in Oxford and took part in his first concert of the tour. During the following months the troupe traveled by coach come rain or come shine, usually giving two concerts at different places every day, with Sundays being their day off. In large cities such as Dublin they had an easier time of it. They performed at several concerts and could stay for some days. But this was an exception. After a last concert on January 29, 1841, in Halifax, it turned out that the financial result was catastrophic. Liszt himself had lost a sum of more than 15,000 Gulden, i.e. more than 43,000 Francs.[99] The troupe returned to London, where Liszt was lent money by Ignaz Moscheles and the publisher Beale of Cramer & Co.

Belgium, Paris, London

On February 3, 1841, Liszt took part in a concert in London given by Jules Benedict. The next day he left for Brussels. Liszt had to cross the Channel again and was again late. Much ice was on the sea, and the captain of Liszt's ship had to wait until he could dare to enter the harbour of Ostend. When Liszt arrived in Brussels late in the evening on February 9, the concert had already ended five hours before. Fétis, director of the Conservatoire in Brussels, organized a private concert on February 11 at which Liszt performed to an audience of 150. Liszt afterwards gave concerts on February 13 in Liège, February 16 in Brussels, February 19 in Liège, February 20 in Ghent, February 24 in Liège and February 26 in Brussels. On March 2 and 4 he gave concerts in Antwerp. After a last concert on March 13 in Brussels, Liszt returned to Paris. By comparison with his former plans, he was two months late in arriving. His plan for a voyage to St. Petersburg and Moscow was therefore cancelled.[100]

Liszt's stay in Paris turned out to be his most successful season since his time as child prodigy. His rival Thalberg, who had announced his own concerts in Paris, changed his plans, performing in Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig and Warsaw instead. In Paris, Liszt gave concerts on March 27 and on April 13 and 25. On March 27 he played his fantasy on "Robert le Diable" which was a huge success. More important, from Liszt's own perspective, was the concert on April 25. It was a charity concert in favour of the Beethoven memorial in Bonn. On April 3 Liszt gave an additional concert in Rouen and on April 28 a concert in Tours. On May 5 he left Paris, travelling via Boulogne to London. At that moment he was convinced that he had at last gained the position in Paris he always coveted.[101]

In London, Liszt performed at several private soirées and at concerts of other artists. However, while Liszt's reputation as virtuoso was steadily increasing, his earnings in London were dismal. In order to solve his financial problems, Liszt was reflecting on an offer he had received from Hamburg. According to this, he should on July 7 take part in a concert at a North German music festival. Around July 10 he should give an own concert in Hamburg besides. Regarding this, he wrote in a letter to Marie d'Agoult of June 16,

The shortage of money in which at the moment I find myself is completely controlling me. If I had earned 10,000 Francs here I would have refused. But now, unless countermanded by your orders, I must follow that rough and commanding voice which shouts to me: "Go you now and march, vagabond!"[102]

On one of the following days, Liszt's financial situation got even worse. In his letter to Marie d'Agoult of June 19 Liszt wrote about an ugly scene that had taken place with Moscheles. Liszt had entirely repaid the money he had lent from Moscheles as well as from Beale.[103] Until the end of his stay in London, Liszt received several letters from Marie d'Agoult with objections against his new ideas. But his decision had already been made. On July 1, after he had performed at a soirée of Lady Ashbourne, Liszt left London for Hamburg. He performed at the concert on July 7 and gave on July 9 an own concert.

Nonnenwerth

After his concert in Hamburg Liszt received an invitation to Copenhagen. He played on July 15 at the Danish court and afterwards gave several concerts.[104] During Liszt's stay in Copenhagen he and Marie d'Agoult agreed to meet around August 4 at Nonnenwerth, a small island in the Rhine near Bonn. At Nonnenwerth they stayed at a hotel that used to be a monastery.

In contrast to his letters to Marie d'Agoult, Liszt had in a letter to Simon Löwy of May 20, 1841, already announced that he would in November 1841 set out for Berlin and pass the whole next winter in Russia.[105] On August 4, shortly before arriving at Nonnenwerth, Liszt wrote in a letter to Count Alberti that he was planning to keep shelling the both banks and of the Rhine with concerts.[106] As a consequence, Liszt's solitude and happiness together with Marie d'Agoult were short-lived.

Liszt in Weimar

In 1847, Liszt gave up public performances on the piano and in the following year finally took up the invitation of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia to settle at Weimar, where he had been appointed Kapellmeister Extraordinaire in 1842, remaining there until 1861. During this period he acted as conductor at court concerts and on special occasions at the theatre, gave lessons to a number of pianists, including Hans von Bülow, who married Liszt's daughter Cosima in 1857 (before her marriage to Richard Wagner). He also wrote articles championing Berlioz and Wagner; which in addition was the time at which his lasting reputations as a truly musical composer (rather than virtuosic performer) was forged. His efforts on behalf of Wagner, who was then an exile in Switzerland, culminated in the first performance of Lohengrin in 1850.

Among his compositions written during his time at Weimar are the first and second piano concertos, the Totentanz, the Concerto pathétique for two pianos, the Piano Sonata in B minor, a number of Etudes, fifteen Hungarian Rhapsodies, twelve orchestral symphonic poems, the Faust Symphony and Dante Symphony, the 13th Psalm for tenor solo, chorus and orchestra, the choruses to Herder's dramatic scenes Prometheus, and the Graner Fest Messe. Much of Liszt's organ music also comes from this period, including the well-known Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale Ad nos, ad salutarem undam and Fantasy and Fugue on the Theme B-A-C-H (the latter also arranged for solo piano).

In 1851 he published a revised version of his 1837 Douze grandes études, now titled Études d'execution transcendante, and the following year the Grandes études de Paganini (Grand etudes after Paganini), the most famous of which is La campanella (The Little Bell), a study in octaves, trills and leaps.

Meets Princess von Sayn-Wittgenstein

Also in 1847, while touring in the Polish Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire), Liszt met Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein. The Princess was an author, whose major work was published in 16 volumes, each containing over 1,600 pages. Her long-winded writing style had some effect on Liszt himself. His biography of Chopin (Life of Chopin) and his chronology and analysis of Gypsy music were both written in the Princess's loquacious style (Grove's Dictionary says that she undoubtedly collaborated with him on this and other works). Princess Carolyne lived with Liszt during his years in Weimar.

Failed marriage attempt

The Princess eventually wished to marry Liszt, but since she had been previously married and her husband, Russian military officer Prince Nikolaus von Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg (1812–1864), was still alive, she had to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that her marriage to him had been invalid. After huge efforts and a monstrously intricate process, she was temporarily successful (September 1860). It was planned that the couple would marry in Rome, on Liszt's 50th birthday, October 22, 1861. Liszt arrived in Rome the previous day, but by the late evening the Princess declined to marry him. It appears that both her husband and the Tsar of Russia had managed to have the Vatican's agreement revoked. The Russian government also impounded her several estates in the Polish Ukraine, which made her later marriage to anybody unfeasible.

Later relations with the Princess

Much later, in a letter of May 30, 1875, she wrote to Eduard Liszt[107] that she had found Liszt to have been ungrateful. While she had spent her money and had lost nearly all of her former fortune, it had been several millions, he had had during all the time of the Weimar years love affairs with other women. Especially in September 1860, there had been an affaire with the singer Emilie Genast. For this reason she had decided that the planned wedding should be cancelled.[108]

The question whether the Princess was correct in her accusations against Liszt, remains open. Regarding Emilie Genast, in the second half of September 1860 she had for a time of about two weeks visited Liszt in Weimar, on his invitation. In the beginning of October she left, travelling to the Rhineland. Liszt composed for her the love song "Wieder möcht' ich Dir begegnen" ("I'm wishing to meet you again"). Besides, he made a new version of his song "Nonnenwerth" as well as orchestrations of the songs "Die junge Nonne", "Gretchen am Spinnrade" and "Song of Mignon" by Schubert. While they were now all dedicated to Emilie Genast, they had in Liszt's youth been strongly correlated with his affair with Marie d'Agoult. "Mignon" has words "Dahin!, dahin möcht' ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn!"[109] (She wants to go together with her darling to Italy.) Reflecting this, Liszt also made a new version of his song "Es rauschen die Winde" with words "Dahin, dahin, sind die Tage der Liebe dahin!" ("the days of love are gone"). From those hints no certain conclusion can be drawn, but Liszt seems to have detected a kind of resemblance between Emilie Genast and the young Marie d'Agoult. However, nearly all of Liszt's letters to Emilie Genast, at least 98, have survived, but are still unpublished; so nothing more can be said.

Might the suspicion of the Princess regarding Emilie Genast insofar have been true or false, it is sure that she was not altogether wrong. It is known from Liszt's correspondence with his mother that in the beginning of 1848 he was in Weimar living together with a Madame F... from Frankfurt-am-Main, a former mistress of Prince Wittgenstein. In March 1848, after Liszt had received a letter of the Princess in which she announced her arrival, Madame F... was very hastily transported to Paris. She visited Liszt’s mother as well as his former secretary Belloni and received an amount of money, telling them that she was pregnant by Liszt. In November 1848 she claimed, she had had an abortion, and disappeared. In 1853 or 1854, Liszt's main mistress was in secret Agnes Street-Klindworth. Liszt visited her for a last time in autumn 1861 in Brussels. It is suspected that the father of some of her children was Liszt.

Liszt in Rome

The 1860s were a period of severe catastrophes in Liszt's private life. After he had on December 13, 1859, already lost his son Daniel, on September 11, 1862, also his daughter Blandine died. In letters to friends Liszt afterwards announced, he would retreat to a solitary living. A more precise impression of his ideas can be gained by looking at his works. On October 22, 1862, his 51st birthday, Liszt took his arrangement of the overture to Wagner's opera Tannhäuser and cut the music illustrating Tannhäuser's living with "Frau Venus" and her ladies away.[110] He had good reasons for identifying him himself with Tannhäuser. One year earlier he had like Tannhäuser travelled from Thuringia to Rome. Like Tannhäuser, also his sins had not been forgiven, as can be seen from his failed marriage. It was Liszt's conclusion that his sexual life had been the cause of his bad luck. He considered a living of continence and resignation as the only appropriate choice for him. There is little doubt that he was insofar following Princess Wittgenstein's advice. It was her opinion that sexuality was the worst of all evils in the world.[111]

Liszt also searched for an adequate environment. He found it at the monastery Madonna del Rosario, just outside Rome, where on June 20, 1863, he took up quarters in a small, Spartan apartment. He had on June 23, 1857, already joined a Franciscan order.[112] On April 25, 1865, he received from Gustav Hohenlohe the tonsure and a first one of the minor orders of the Catholic Church. Three further minor orders followed on July 30, 1865. Until then, Liszt was Porter, Lector, Exorcist, and Acolyte. While Princess Wittgenstein tried to persuade him to proceed in order to become priest, he did not follow her. In his later years he explained, he had wanted to preserve a rest of his freedom.[113] By chance, there was a worldly counterpoint to Liszt's becoming ecclesiastic. In the second half of 1865 his two "Episoden aus Lenaus Faust" appeared. The first piece, the "1st Mephisto-Waltz", musically paints a vulgar scene in a village inn. Was this coincidence merely an accident,[114] the transcriptions of the pieces "Confutatis maledictis" and "Lacrymosa" of Mozart's Requiem, which Liszt made on January 21, 1865,[115] were in a better sense characteristic for him. As child prodigy he had been compared and equalled with the child Mozart. While this aspect of his personality had died, he had in 1865 a rebirth as "Abbé Liszt".

During the 1860s in Rome, Liszt's main works were sacral works such as the oratorios Die Legende von der Heiligen Elisabeth and Christus as well as masses such as the Missa choralis and the Ungarische Krönungsmesse. For many of his piano works Liszt also took sacral subjects. Examples are the piece "À la Chapelle Sixtine" on melodies by Mozart and Allegri, the two pieces "Alleluja" and "Ave Maria d'Arcadelt", and the two Legends "St. François d'Assise" and "St. François de Paule, marchant sur les flots". The two pieces "Illustrations de l'Africaine" on melodies by Meyerbeer are at least in parts of a sacral style.[116] The same goes for the transcription of a scene of Verdi's opera Don Carlos. But, besides, Liszt still composed works on worldly subjects. Examples of this kind are the concert etudes "Waldesrauschen" and "Gnomenreigen" as well as the fantasy on Mosonyi's opera Szep Ilonka and the transcription of the final scene "Liebestod" of Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde. Further examples are the pieces "Rêverie sur un motif de l'opéra Roméo et Juliette" and "Les sabéennes, Berceuse de l'opéra La Reine de Saba" after Gounod.

At some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On March 26, 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a program of sacral music. The "Seligkeiten" of his Christus-Oratorio and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Haydn's Die Schöpfung and works by J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Jornelli, Mendelssohn and Palestrina were performed. On January 4, 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his Christus-Oratorio, and on February 26, 1866, his Dante Symphony. There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions. Bódog Pichler, who visited Liszt in 1864 and asked him for his future plans, had the impression that Rome's musical life was not satisfying for Liszt.

Threefold life

Liszt returned to Weimar in 1869. He began a series of piano master classes there, which he would teach a few months every year. From 1876 he also taught for several months every year at the Hungarian Music Academy at Budapest. He continued to live part of each year in Rome, as well. Liszt continued this threefold existence, as he is said to have called it, for the rest of his life.

Last years

From 1876 until his death he also taught for several months every year at the Hungarian Conservatoire at Budapest. On July 2, 1881, Liszt fell down the stairs of the Hofgärtnerei in Weimar. Though friends and colleagues had noted swelling in Liszt's feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month, Liszt had up to this point been in reasonably good health, his body retained the slimness and suppleness of earlier years. The accident, which immobilized him eight weeks, changed all this. A number of ailments manifested—dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract of the left eye and chronic heart disease. The latter would eventually contribute to Liszt's death. He would become increasingly plagued with feelings of desolation, despair and death—feelings he would continue to express nakedly in his works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."[117]

Liszt's last concert was performed at the Casino Bourgeois in Luxembourg on July 19, 1886.[118]

He died in Bayreuth on July 31, 1886, officially as a result of pneumonia which he may have contracted during the Bayreuth Festival hosted by his daughter Cosima. At first, he was surrounded by some of his more adoring pupils, including Arthur Friedheim, Siloti and Bernhard Stavenhagen, but they were denied access to his room by Cosima shortly before his death at 11:30 p.m. He is buried in the Bayreuth cemetery. Questions have been posed as to whether medical malpractice played a direct part in Liszt's demise. At 11:30 Liszt was given two injections in the area of the heart. Some sources have claimed these were injections of morphine. Others have claimed the injections were of camphor, shallow injections of which, followed by massage, would warm the body. An accidental injection of camphor into the heart itself would result in a swift infarction and death. This series of events is exactly what Lina Schmalhausen describes in the eyewitness account in her private diary, the most detailed source regarding Liszt's final illness.[119]

References

- ↑ https://books.google.com.au/books?id=A4OVdTt3UMsC&pg=PA4&lpg=PA4&dq=greatest+pianist+of+all+time+liszt&source=bl&ots=Lojy5T7fPt&sig=oRiOFmwnArKLxSYHneQOsXeIwqc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj05o-tisDUAhXBVbwKHQgzAr04ChDoAQhdMAk#v=onepage&q=greatest%20pianist%20of%20all%20time%20liszt&f=false

- ↑ Óvári: Ferenc Liszt, p. 78. Liszt's former teacher at the school of Raiding, Johann Rohrer, himself had to learn Hungarian at this time.

- ↑ Compare Coby Lubliner's intriguing essay How Hungarian was Liszt?. The house in Raiding where Liszt was born has two doors. Above the left door, a German inscription of 1926 describes him as the German master Franz Liszt. Above the right door, in a Hungarian inscription of 1881, he is Liszt Ferencz. The nationality question was left open in the second case. See also Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 18. In an inscription of the late 1870s at the door of his home at the Conservatoire in Budapest, he was both. In the Hungarian first part he was Liszt Ferencz, and in the German second part Franz Liszt. See also Hamburger, Klara: Franz Liszt, Beiträge von ungarischen Autoren, Budapest 1978, picture 15, after p. 192.

- ↑ Burgenland newsletters

- ↑ Liszt Ferenc, származása és családja ("Franz Liszt, origin and family"). The book was published 1973, Editio musica, Budapest, after Békefi's death.

- 1 2 3 Ramann, Lina: Franz Liszt, Als Künstler und Mensch, vol. 1, Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1880, pp. 3–11

- ↑ Haraszti, Émile: Franz Liszt, Paris 1967, and Bartók, Béla: Liszt-Probleme, in: Franz Liszt, Beiträge von ungarischen Autoren, ed. Klara Hamburger, Budapest 1978, pp. 122ff; also see: Gooley, Dana Andrew: The virtuoso Liszt, Cambridge University Press 2004, where many examples from the time around 1840 can be found.

- 1 2 Szennyei József: Magyar Írók élete és munkái VII (Köberich-Loysch) Budapest. Hornyánszky 1900

- ↑ Szennyei József: Magyar Írók élete és munkái, (Entries: List) Budapest 1900

- 1 2 3 Sir William Henry Hadow: A Croatian Composer (=Haydn) First Edition in 1897, London, reprinted in 1972, New York

- ↑ >Levelezés Közli Ipolyi Arnold (1871) (Stephani Liszt) by Miklós Oláh Published 1876 AMT Akadémiai Könyvkiadó Hivatal 639 pages. Original from Harvard University Digitizes May 30, 2006: Chapter XI, Sopronii die 13. mensis Junii 1684.

Per magnificam olim Dominam Susannam Gyulaffy, Magnifici condam Domini Stephani Liszty relictam viduam Valentino Szenté donatum. Per eum viro Celsissimo Dominó Comiti Paulo Eszterhazi, hodic concordi imiversorum Statuum et Ordinum voto et desiderio in Regni Hungáriáé Palatimim electo tamquam libri huius Dominó proprietario restitutus et luimillime presentatus per Valentinum Szenté manu propria. - ↑ Peter Raabe: Franz Liszt, 2 Bände, 1931

- ↑ Nyugat/1936/1936.3 szám Barók Béla: Liszt Ferenc Szekfoglaló a M. Tud. Akadémiában (The inauguration speech of Béla Bartók at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences) "hogy apjának családja magyar, német, vagy talán szláv eredetû-e, az okmányszerüleg úgylátszik nem deríthetõ ki."

- ↑ Walker, Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years, 1811–1847

- ↑ "Coby Lubliner: How Hungarian was Liszt?". University of California, Berekeley. August 15, 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Victor and Marina Ledin, Encore Consultants, Music notes in CD: Franz Liszt Complete Piano music, volume 4 NAXOS 1997

- 1 2 Jung: Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen

- ↑ Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern.

- ↑ See the review of October 17, 1823, in: Schilling: Franz Liszt, p. 232. The review was reprinted in Augsburg; see Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 29.

- ↑ See Adam Liszt's letter to Czerny of July 29, 1824, in Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 36.

- ↑ See Rellstab, Franz Liszt, p. 64. According to a note on the same page, Liszt confirmed this account in Rellstab's presence. Liszt exclaimed that transposing had been a very hard task for him. He often had had to stop and he had made many mistakes.

- ↑ The advantage of the new mechanics was that repeated notes could be played without completely releasing a key. According to Adam Liszt's letter to Czerny of March 17, 1824, Erard until then had made only three such pianos. He wanted to make a fourth one for Liszt. See Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 32.

- ↑ See: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 437.

- ↑ Usual rates were 4% or 5%, which would equal an annual income of 2,400–3,000 Francs.

- ↑ Rellstab: Franz Liszt, p. 65.

- ↑ Rellstab: Franz Liszt, p. 66.

- ↑ For example, see Liszt's letter to his son Daniel of April 20, 1854, in: Jung: Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, p. 130f.

- ↑ Ramann: Lisztiana, p. 408.

- ↑ While "loch" is "hole", the German word "Ratzen" can be taken with different meanings. Firstly, "Ratzen" is a very old form of "Ratten" ("rats"). Secondly, "ratzen" can in common speech be used with meaning of "to sleep". Thirdly, it can also be taken as vulgar expression for "having sex". The third meaning was used by Liszt himself in his pocket calendar.

- ↑ Walker, in Virtuoso Years, p. 135, mysteriously wrote: "Despite Madame Alix's assurance of his 'good health', it is evident that Liszt was still chronically ill." Liszt was not the only artist who had the pleasure of reading his own obituary.

- ↑ See Marie d'Agoult's description in: Souvenirs I, p. 236, where List himself is mentioned.

- ↑ See the following chapter.

- ↑ Goubault, Christian: Les trois concerts de Franz Liszt a Rouen, in: Revue internationale de musique française 13 (1984), pp. 90ff.

- ↑ Correspondance de Frédéric Chopin, L'ascension 1831–1840; Recueillie, révisée, annotée et traduite par Bronislas Éduard Sydow en collaboration avec Suzanne et Denise Chainaye, Paris 1956, p. 40.

- ↑ Mendelssohn: Reisebriefe, p. 315.

- ↑ See Père Enfantin's brochure „Dans la réunion générale de la famille“ of November 19, 1831, and the article "De la femme" by Duveyrier in La Globe of January 12, 1832. Because of the brochure and the article, the meeting place of the Saint-Simonists on the Rue Taibot was closed by the police on January 22, 1832. In August 1832, Enfantin and Duveyrier were tried, sentenced to a year in jail, and fined 100 Francs. See Oeuvres de Saint-Simon & d'Enfantin, publiées par les membres du conseil institué par Enfantin pour l'exécution de ses dernières volontés, quarante-septième volume de la collection générale, reprint of 1865–78 edition, Aalen, Otto Zeller 1964.

- ↑ See Mendelssohn's letter to his family of January 14, 1832, in: Mendelssohn: Reisebriefe , p. 325.

- ↑ See his letter to George Sand of autumn 1835, in Marix-Spire: Le cas George Sand, p. 614. While still in Geneva, Liszt reread the brochure „Dans la réunion générale de la famille“ with much enthusiasm. Walker's statement, in: Virtuoso Years, p. 154, that Liszt's interest in Saint-Simonism had waned is therefore wrong.

- ↑ Barbey-Boissier: La Comtesse de Gasparin et de sa famille, Correspondance et souvenirs 1813–1894, Tome premier, Paris 1902, p. 156f. The Comtesse de Gasparin was Liszt's former student Valerie Boissier.

- ↑ The date is known from Liszt's pocket calendar.

- ↑ He was not unique in that desire, for there were many "piano-Paganinis" in those days. Thalberg received that rank from Rossini; see Mühsam, Gerd: Sigismund Thalberg als Klavierkomponist, Wien 1937, p. 100. Schumann, during parts of his youth, also hoped to model himself on Paganini.

- ↑ For an English translation, see Walker: Virtuoso Years, p. 173f.

- ↑ Liszt: Briefe Erster Teil, p. 8. According to a letter by his mother of May 12, 1832, in: Liszt: Briefwechsel mit seiner Mutter, p. 320, he had left Paris on May 7.

- ↑ The fantasy has the usual form of introduction, theme, variations and finale. In the Ecoutebœuf version, two variations are included. The second variation was not completed, and the finale was still missing. In the final version, the second variation was omitted.

- ↑ See Liszt's letter to Jules Janin, in Vier: L'artiste – le clerc, p. 145. Also see the note in Le Pianiste of November 20, 1834, p. 16.

- ↑ In 1872, after she had died, Liszt wrote in a letter to Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, "She [Caroline] was one of the purest manifestations of God's blessing on earth"; see Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 54.

- ↑ A characteristic example is Walker: Virtuoso Years, pp. 131ff. Walker did his best to conceal the chronology by giving no explicit date for the tragic end of the love affair. But he had to submit that between the beginning and the end of the affaire there was a gap of two years. After this, his comments on p. 133, regarding Liszt's concert activities of April 1828 (!), calling them "at the height of the Saint-Cricq affaire" (!), have not been based on documented evidence.

- ↑ Gert Nieveld, Caroline de Saint-Cricq: Siren with the heart of ice, The Liszt Society Journal, Bicentenary Edition, Volume 31, 2011, ISSN 0141-0792

- ↑ "Saint Cricq – Details of 1828 romance between Franz Liszt and Countess Caroline de Saint-Cricq".

- ↑ Imagining Liszt as happily married to Caroline de Saint-Cricq is not an easy task.

- ↑ Her full name was Jeanne Frédérique Athénais de Saint-Hippolyte, Comtesse de Benoist de la Prunarède

- 1 2 Walker: Virtuoso Years, p. 149.

- ↑ Translated from French after Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 72.

- ↑ In contrast, Walker: Virtuoso Years, p. 149. Walker wrote that the voyage took place in 1832. But the source in his n.10 is an entry of March 23, 1832, in Auguste Boissier's diary: "Also, he met again a certain Madmoiselle de Barré together with whom he one year ago had made a voyage to the Savoy".

- ↑ Bellas, Jacqueline: Liszt et la fille de Madame D..., in: Littératures, Université de Toulouse, no 2, automne 1980, pp. 133ff. In Walker's Virtuoso Years, p. 149, n. 12, Euphémie has simultaneously turned into her own mother as well as into her grandmother.

- ↑ Pocknell: Liszt à Bourges.

- ↑ See his letters to Valerie Boissier of December 12, 1832, and of May 31, 1833, in Bory: Diverses lettres inédites, pp. 11ff.

- ↑ The piece can be described as variations following a unified compositional idea in a rather complicated quasi chamber-music style.

- ↑ Her presence can be concluded from a letter by Liszt of October 30, 1833, in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 47. Liszt suggested to her in a letter going to hear the Symphony-fantastique again after eleven months, which could only refer to the single performance of the symphony on December 9. Liszt's presence is known from an entry of December 9, 1832, in Antoine Fontaney's diary; see Fontaney, Antoine: Journal intime, publié avec une introduction et des notes par René Jasinski, Paris 1925, p. 163f. On that date Liszt was seen sharing a box seat with Victor Hugo and his wife.

- ↑ See his letter to Valerie Boissier of May 31, in Bory: Diverses lettres inédites, p. 12f.

- ↑ Dupêchez: Marie d'Agoult, p. 312f, n. 66.

- ↑ Dupêchez: Marie d'Agoult, p. 343.

- ↑ See her letter to her mother of December 25, 1832, in Vier: Comtesse d'Agoult I, p. 130 and p. 363, n. 300.

- ↑ Dupêchez: Marie d'Agoult, p. 54.

- ↑ After the golden age: romantic pianism and modern performance by Kenneth Hamilton, p. 83, Oxford University Press 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-517826-5

- ↑ "Liszt at the Piano" by Edward Swenson, June 2006

- ↑ "The picture agency bpk is a central media service provider of all devices of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz) and of over 100 major museums and libraries abroad.".

- ↑ The Memoirs were projected to five parts, but never completed. They are not to be confused with Alan Walker's source "AM"; comp. Virtuoso Years, p. 449. Walker's "AM" is a heavily redacted compilation of parts of Marie d'Agoult's autobiographical manuscripts, published 50 years after her death.

- ↑ d'Agoult: Souvenirs I, p. 298. In parts of the older Liszt literature, this date —although erroneous— was accepted. Traces can still be found in Walker's Virtuoso Years, p. 190. In the beginning of 1833, Liszt indeed was 21. But Marie d'Agoult, born on December 30, 1805 (per a contemporary custom, December 31 was taken as her birthday), was not 28 as claimed by Walker, but 27.

- ↑ d'Agoult: Souvenirs I, p. 420f, n. 162; the year was misprinted as 1883, although obviously 1833 was meant.

- ↑ See d'Agoult: Souvenirs I, p. 261f.

- ↑ Marie d'Agoult's letter to her mother of December 25, 1832, in Vier: Comtesse d'Agoult I, p. 130. The letter includes a name which Vier could not decipher. According to d'Agoult: Souvenirs I, p.420, n.160, it is the name of the Duchess Rauzan who received Marie d'Agoult's visit on December 22. Liszt was well acquainted also with the Duchess. He felt a most desperate adoration for her; compare Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 19.

- ↑ Apponyi, Rodolphe: Vingt-cinq ans a Paris (1826–1850), Journal du Comte Rodolphe Apponyi, Attaché de l'ambassade d'Autriche a Paris, Publié par Ernest Daudet, (1831–1834), Paris 1914, p. 306. It was a typical soiree which included artists such as Rossini, Chopin and Kalkbenner, as well as the singers Tamburini, Rubini and Giulia Grisi.

- ↑ Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 107. For some reason Liszt preferred to use the name of Jules de Saint-Félix as a pseudonym.

- ↑ Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 65. It is to be presumed that she wore a uniform of her husband's; compare the quotation from Charles d'Agoult's Memoirs in Walker: Virtuoso Years, p. 198.

- ↑ Important forms of the nickname, as found in sources, are the abbreviations "B. V." and "Vieux". In some of his letters, Liszt himself took the Italian version "Vecchio".

- ↑ See Liszt's letters of May 5 and 16, in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 69 and p. 76. In the first letter Liszt complains that he had heard nothing of Marie d'Agoult for a week. According to the second letter, she had left Paris on a Monday, which was April 28.

- ↑ Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 83.

- ↑ Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 88f.

- ↑ See his letter written that day, in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 95f. The date is "Dimanche 11 heures" ("Sunday, 11 o'clock"), which means June 22.

- ↑ The date of her departure can be determined from a letter by Liszt of July 1, in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 97.

- ↑ See his letters in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 97 and p. 104.

- ↑ See his letter to Valerie Boissier, in Bory: Diverses lettres inédites, pp. 15ff.

- ↑ See Liszt's letter to Marie d'Agoult of August 25, 1834, in: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 109.

- ↑ Sand: Correspondance II, p. 777.

- ↑ For the first letter see Sand: Correspondance II, p. 791. The letter was written on a Sunday but postmarked Monday, January 19. For the second letter see Sand: Correspondance II, p. 794.

- ↑ Lamennais: Correspondance générale VI, p. 823f, and Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p. 130.

- ↑ All pages in his pocket calendar are blank; and there are no letters to his mother, Marie d'Agoult, George Sand or anyone else. Nevertheless, by collecting some small hints a hypothesis can be built. It might have been in this time when Liszt —surrounded by snow and ice— was together with Adèle de Laprunarède marooned in Marlioz. See Protzies: Studien zur Biographie Franz Liszts, p. 45f.

- ↑ A marble inscription put up there in 1896 in Liszt's memory was replaced in 1938 by an image of the old (!) Liszt. See Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 80.

- ↑ Lehmann had become one of Liszt's and Marie d'Agoult's closest friends. For some reasons it might be suspected that Daniel was Lehmann's son.

- ↑ It was exactly this point of view which Liszt himself, three and a half years earlier, had taken in his review of selected piano works of Thalberg.

- ↑ The Parisian point of view with regards to the sabre was shared widely in the Europe outside of Hungary. For details, see Gooley: The Virtuoso Liszt, p. 143ff.

- ↑ Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p. 43.

- ↑ At the end of 1839, the subscribers to the Revue et Gazette musicale had received an "Album du pianiste" with new piano pieces, including Thalberg's fantasy "La Donna del Lago", op. 40.

- ↑ Fantastic Cavalcade, Liszt's British Tours of 1840 & 1841 from the Diarys of John Orlando Parry, in: Liszt Society Journal 6 (1981), pp. 2ff, and Liszt Society Journal 7 (1982), pp. 16ff.

- ↑ See Liszt's letter of September 16, 1840, in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p. 26.

- ↑ See Marie d'Agoult's letter of August 22, 1840, in Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p. 13.

- ↑ Liszt played for the first time his fantasy on "Robert le Diable", composed on his way from Fontainebleau to Hamburg. According to Liszt's own account in Lachmund, Carl: Mein Leben mit Franz Liszt, Aus dem Tagebuch eines Liszt-Schülers, ed. Mabel Wagnalls, Eschwege 1970, p. 76f, the performance had been "ein halber Mißerfolg" ("half a failure"), since Liszt had not found enough time for practising the piece.

- ↑ See Liszt's letter to Franz Schober of April 30, 1841, in Jung: Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, p. 78. The exchange rate was taken from a note in the Revue et Gazette musicale of January 7, 1841, p. 24. For a comparison: A villa in Paris with twelve rooms could be bought for 25,000 Francs.

- ↑ For her part, Clara Schumann could not go to Russia, since she was pregnant with her first daughter Marie.

- ↑ For example, see Liszt's letter to Princess Belgiojoso of May 18, 1841, in Ollivier: Autour de Mme d'Agoult et de Liszt, p. 176. The date is erroneously given as March 18.

- ↑ Translated from French after Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p. 161.

- ↑ Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p. 162. Liszt did not want to give further details. But he wrote that Moscheles' Jewish character had broken through, whatever he meant by that.

- ↑ Liszt's programs can be found in: Johnson, Bengt: Liszt og Danmark, in: Dansk musiktidsskrift 37 (1962), pp. 79ff, and p. 38 (1963), pp. 81ff. Although most frequently the contrary has been claimed, the Danish King could not possibly have "exceptionally liked" the Don Juan-fantasy, later dedicated to him. Liszt —during his stay in Copenhagen— played the fantasy neither for the King nor at his concerts.

- ↑ Liszts Briefe, Erster Teil, p. 43. The "whole next winter" was meant as the "whole next winter concert season", i.e., until the end of April 1842.

- ↑ Pocknell, Pauline (ed.): Franz Liszt: Fifteen Autograph Letters (1841–1883) in the William Ready Division of Archives & Research Collections, Mills Memorial Library, McMaster University Canada, in: Journal of the American Liszt Society 39 (January – June 1996), p. 4.

- ↑ Eduard Liszt, born January 31, 1817, was the 25th and youngest child of Franz Liszt's grandfather Georg. His mother was Georg List's third wife Magdalene Richter.

- ↑ The letter can be found in: Franz Liszt und sein Kreis in Briefen und Dokumenten aus den Beständen des Burgenländischen Landesmuseums, ed. Maria Eckhardt and Cornelia Knotik, Eisenstadt 1983, pp. 66ff. Also see the letter to Eduard Liszt of December 20, 1861, pp. 39ff, which shows that the Princess had lost most of her former fortune. She was prepared that after further 6, 8 or 10 years there would be nothing left. While she had owned millions in former times, she would then live in absolute poverty, hoping for some alms from the husband of her daughter. Liszt still owned a sum of about 220,000 Francs, deposed at the bank of Rothschildt in Paris. But this money was in his will destined as gift for his daughters.

- ↑ "Mignon", poem (in German)

- ↑ Compare the description of the manuscript of the "Choeur des Pèlerins, Aus der Oper Tannhäuser von Richard Wagner", in the New Liszt Edition, Vol. II/12, p. XVIIf.

- ↑ Many examples can be found in: Ramann: Lisztiana.

- ↑ See the document in: Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p. 209.

- ↑ Compare Ramann: Lisztiana, p. 198.

- ↑ Liszt's letter to Alexander Wilhelm Gottschalg of January 25, 1866, in: Jung: Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, p. 202, shows that the publisher Julius Schuberth was responsible for the coincidence. The piece had already been composed at end of the Weimar years.

- ↑ For the date, see: New Liszt Edition, Vol. II/24, p. 176. Liszt might have thought of Mozart's birthday, which was on January 27.

- ↑ The first piece is a prayer, and the second piece has two choral episodes.

- ↑ Walker: Final Years.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ Walker: Final Years, p. 508, p. 515 with n. 18.

Bibliography

- Bory, Robert: Diverses lettres inédites de Liszt, in: Schweizerisches Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft 3 (1928).

- Bory, Robert: Une retraite romantique en Suisse, Liszt et la Comtesse d'Agoult, Lausanne 1930.

- Burger, Ernst: Franz Liszt, Eine Lebenschronik in Bildern und Dokumenten, München 1986.

- Chiappari, Luciano: Liszt a Firenze, Pisa e Lucca, Pacini, Pisa 1989.

- d'Agoult, Marie (Daniel Stern): Mémoires, Souvenirs et Journaux I/II, Présentation et Notes de Charles F. Dupêchez, Mercure de France 1990.

- Dupêchez, Charles F.: Marie d'Agoult 1805–1876, 2e édition corrigée, Paris 1994.

- Gut, Serge: Liszt, De Falois, Paris 1989.

- Jerger, Wilhelm (ed.): The Piano Master Classes of Franz Liszt 1884–1886, Diary Notes of August Gollerich, translated by Richard Louis Zimdars, Indiana University Press 1996.

- Jung, Franz Rudolf (ed.): Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, Berlin 1987.

- Keeling, Geraldine: Liszt's Appearances in Parisian Concerts, Part 1: 1824–1833, in: Liszt Society Journal 11 (1986), p. 22ff, Part 2: 1834–1844, in: Liszt Society Journal 12 (1987), p. 8ff.

- Legány, Deszö: Franz Liszt, Unbekannte Presse und Briefe aus Wien 1822–1886, Wien 1984.

- Liszt, Franz: Briefwechsel mit seiner Mutter, edited and annotated by Klara Hamburger, Eisenstadt 2000.

- Liszt, Franz and d'Agoult, Marie: Correspondence, ed. Daniel Ollivier, Tome 1: 1833–1840, Paris 1933, Tome II: 1840–1864, Paris 1934.

- Marix-Spire, Thérése: Les romantiques et la musique, le cas George Sand, Paris 1954.

- Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Felix: Reisebriefe aus den Jahren 1830 bis 1832, ed. Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Leipzig 1864.

- Ollivier, Daniel: Autour de Mme d'Agoult et de Liszt, Paris 1941.

- Óvári, Jósef: Ferenc Liszt, Budapest 2003.

- Protzies, Günther: Studien zur Biographie Franz Liszts und zu ausgewählten seiner Klavierwerke in der Zeit der Jahre 1828–1846, Bochum 2004.

- Raabe, Peter: Liszts Schaffen, Cotta, Stuttgart und Berlin 1931.

- Ramann, Lina: Liszt-Pädagogium, Reprint of the edition Leipzig 1902, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden, 1986.

- Ramann, Lina: Lisztiana, Erinnerungen an Franz Liszt in Tagebuchblättern, Briefen und Dokumenten aus den Jahren 1873–1886/87, ed. Arthur Seidl, text revision by Friedrich Schnapp, Mainz 1983.

- Redepenning, Dorothea: Das Spätwerk Franz Liszts: Bearbeitungen eigener Kompositionen, Hamburger Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 27, Hamburg 1984.

- Rellstab, Ludwig: Franz Liszt, Berlin 1842.

- ed Sadie, Stanley, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, First Edition (London: Macmillian, 1980). ISBN 0-333-23111-2

- Searle, Humphrey, "Liszt, Franz"

- Sand, George: Correspondence, Textes réunis, classés et annotés par Georges Lubin, Tome 1 (1812–1831), Tome 2 (1832 – Juin 1835), Tome 3 (Juillet 1835 – Avril 1837), Paris 1964, 1966, 1967.

- Saffle, Michael: Liszt in Germany, 1840–1845, Franz Liszt Studies Series No.2, Pendragon Press, Stuyvesant, New York, 1994.

- Schilling, Gustav: Franz Liszt, Stuttgart 1844.

- Vier, Jacques: Marie d'Agoult – Son mari – ses amis: Documents inédits, Paris 1950.

- Vier, Jacques: La Comtesse d'Agoult et son temps, Tome 1, Paris 1958.

- Vier, Jacques: L'artiste – le clerc: Documents inédits, Paris 1950.

- Walker, Alan: Franz Liszt, The Virtuoso Years (1811–1847), revised edition, Cornell University Press 1987.