Arthur Percival

| Arthur Ernest Percival | |

|---|---|

Percival, pictured here as GOC Malaya Command, December 1941. | |

| Born |

26 December 1887 Aspenden, Hertfordshire, England |

| Died |

31 January 1966 (aged 78) Westminster, London, England |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1946 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-General |

| Unit |

Essex Regiment Cheshire Regiment |

| Commands held |

Malaya Command (1941–42) 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division (1940–41) 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division (1940) 2nd Battalion, Cheshire Regiment (1932–34) 7th (Service) Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment (1918) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Companion of the Order of the Bath Distinguished Service Order & Bar Officer of the Order of the British Empire Military Cross Mentioned in Despatches (3) Croix de guerre (France) |

Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival, CB, DSO & Bar, OBE, MC, OStJ, DL (26 December 1887 – 31 January 1966) was a senior British Army officer. He saw service in the First World War and built a successful military career during the interwar period but is most noted for his defeat in the Second World War, when he commanded British Commonwealth forces during the Japanese Malayan Campaign and the subsequent Battle of Singapore.

Percival's surrender to the invading Imperial Japanese Army force, the largest capitulation in British military history, undermined Britain's prestige as an imperial power in East Asia.[1][2] His defenders, such as Sir John Smyth, have argued that under-funding of Malaya's defences and the inexperienced, under-equipped nature of the Commonwealth army, not Percival's leadership, were ultimately to blame.[3]

Early life

Childhood and employment

Arthur Ernest Percival was born on 26 December 1887 in Aspenden Lodge, Aspenden near Buntingford in Hertfordshire, England, the second son of Alfred Reginald and Edith Percival (née Miller). His father was the Land Agent of the Hamel's Park estate and his mother came from a Lancashire cotton family.[4]

Percival was initially schooled locally in Bengeo. Then in 1901, he was sent to Rugby with his more academically successful brother, where he was a boarder in School House. A moderate pupil, he studied Greek and Latin but was described by a teacher as "not a good classic".[5] Percival's only qualification on leaving in 1906 was a higher school certificate. He was a more successful sportsman, playing cricket and tennis and running cross country.[6] He also rose to colour sergeant in the school's Volunteer Rifle Corps. However, his military career began at a comparatively late age: although a member of Youngsbury Rifle Club, he was still working as a clerk for the iron ore merchants Naylor, Benzon & Company Limited in London, which he had joined in 1914, when the Great War broke out.

Enlistment and First World War

Percival enlisted on the first day of the war as a private in the Officer Training Corps of the Inns of Court, at the age of 26, and was promoted after five weeks' basic training to temporary second lieutenant.[7] Nearly one third of his fellow recruits would be dead by the end of the war. By November Percival had been promoted to captain.[8] The following year he was dispatched to France with the newly formed 7th (Service) Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment,[7] which became part of the 54th Brigade, 18th (Eastern) Division in February 1915. The first day of the Battle of the Somme (1 July 1916) left Percival unscathed, but in September he was badly wounded in four places by shrapnel, as he led his company in an assault on the Schwaben Redoubt, beyond the ruins of Thiepval village, and was awarded the Military Cross.[9]

Percival took a regular commission as a captain with the Essex Regiment in October 1916,[10] whilst recovering from his injuries in hospital. He was appointed a temporary major in his original regiment.[11] In 1917, he became battalion commander with the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel.[12][13][14][15][16] During Germany's Spring Offensive, Percival led a counter-attack that saved a unit of French artillery from capture, winning a Croix de Guerre.[17] For a short period in May 1918, he acted as commander of the 54th Brigade. He was given brevet promotion to major,[18] and awarded the Distinguished Service Order, with his citation noting his "power of command and knowledge of tactics".[19] He ended the war as a respected soldier, described as "very efficient" and was recommended for the Staff College.[20]

Between the wars

Russia

Percival's studies were delayed in 1919 when he decided to volunteer for service with the Archangel Command of the British Military Mission during the North Russia Campaign of the Russian Civil War. Acting as second-in-command of the 45th Royal Fusiliers, he earned a bar to his DSO in August, when his attack in the Gorodok operation along the Dvina netted 400 Red Army prisoners. The citation reads:

He commanded the Gorodok column on 9–10 August 1919, with great gallantry and skill, and owing to the success of this column the forces on the right bank of the Dvina were able to capture all its objectives. During the enemy counter-attack from Selmenga on Gorodok he handled his men excellently. The enemy were repulsed with great loss, leaving 400 prisoners in our hands.[21]

Ireland

In 1920 Percival served in Ireland against the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Anglo-Irish War, first as a company commander and later the intelligence officer of the 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment, in Kinsale, County Cork.[22]

Percival proved himself an energetic counter-guerrilla, noted for his aptitude for intelligence-gathering and the establishment of bicycle-riding 'Mobile Columns'. He was accused of brutality towards prisoners,[23] including the use of strikes of a rifle butt to the head, pincers to pull fingernails and burning cigarettes on the body. These accusations were substantiated by prisoners' testimony[24] but the veracity of the accounts have been challenged by both colleagues and historians.[25]

Following the IRA killing of a Royal Irish Constabulary sergeant outside Bandon church in July 1920, Percival captured Tom Hales, commander of the IRA's West Cork Brigade, and Patrick Harte, the brigade's quartermaster, for which he was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). Both prisoners later claimed to have been repeatedly beaten and tortured while in custody. Hales alleged that a pair of pliers had been used on his lower body and to extract his fingernails. Harte suffered brain injury and died in a mental hospital in 1925. The claims of torture were denied by Percival and his colleagues, Hales being unable to produce any visible wounds beyond missing teeth and Harte's head injury being officially recorded as the result of being rifle-butted upon arrest.[26][27][28] Ormonde Winter, the head of British Intelligence in Dublin Castle, later named Hales as an informer who had invented the story as an excuse for providing the names of his fellow IRA members in return for a lesser sentence.[29][30]

The IRA badly wanted to kill Percival, accusing him of running what they called the 'Essex Battalion Torture Squad'. A first attempted assassination by Tom Barry in Bandon failed when Percival departed from his dinnertime routine. A second assassination squad was dispatched to London in March 1921, but was forced to abandon the planned attack in Liverpool Street Station when they learned that the Metropolitan Police knew of their plans. David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill met Percival in 1921, when he was called as an expert witness during an inquiry into the Anglo-Irish War.[31]

Percival would later deliver a series of lectures on his experiences in Ireland in which he stressed the importance of surprise and offensive action, intelligence-gathering, maintaining security and co-operation between the security forces.[32]

Staff officer

Percival attended the Staff College, Camberley from 1923[33] to 1924, then commanded by General Edmund Ironside, where he was taught by J.F.C. Fuller, who was one of the few sympathetic reviewers of his book, The War in Malaya, twenty-five years later. He impressed his instructors, who picked him out as one of eight students for accelerated promotion, and his fellow students who admired his cricketing skills. Following an appointment as major with the Cheshire Regiment, he spent four years with the Nigeria Regiment of the Royal West African Frontier Force in West Africa as a staff officer.[34][35] He was given brevet promotion to lieutenant-colonel in 1929.[36]

In 1930, Percival spent a year studying at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. From 1931 to 1932, Percival was General Staff Officer Grade 2, an instructor at the Staff College. The College's commandant General Sir John Dill, became Percival's mentor over the next 10 years, helping to ensure his protégé's advancement. Dill regarded Percival as a promising officer and wrote that "he has an outstanding ability, wide military knowledge, good judgment and is a very quick and accurate worker" but added "he has not altogether an impressive presence and one may therefore fail, at first meeting him, to appreciate his sterling worth".[37] With Dill's support, Percival was appointed to command the 2nd Battalion, the Cheshire Regiment from 1932[38] to 1936, initially in Malta. In 1935, he attended the Imperial Defence College.[4]

Percival was made a full colonel in March 1936,[39] and until 1938[40] he was General Staff Officer Grade 1 in Malaya, the Chief of Staff to General Dobbie, the General Officer Commanding in Malaya. During this time, he recognised that Singapore was no longer an isolated fortress.[41] He considered the possibility of the Japanese landing in Thailand to "burgle Malaya by the backdoor[42] and conducted an appraisal of the possibility of an attack being launched on Singapore from the North, which was supplied to the War Office, and which Percival subsequently felt was similar to the plan followed by the Japanese in 1941.[43] He also supported Dobbie's unexecuted plan for the construction of fixed defences in Southern Johore. In March 1938, he returned to Britain and was (temporarily) promoted to brigadier on the General Staff, Aldershot Command.[44]

Second World War

Percival was appointed Brigadier, General Staff, of the I Corps, British Expeditionary Force, commanded by General Dill, from 1939 to 1940. He was then promoted to acting major-general,[45] and in February 1940 briefly became General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. He was made Assistant Chief of the Imperial General Staff at the War Office in 1940 but asked for a transfer to an active command after the Dunkirk evacuation.[46][47] Given command of the 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division, he spent 9 months organising the protection of 62 miles (100 km) of the English coast from invasion.[48] He was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in the 1941 King's Birthday Honours.[49]

Percival's early assessment of the vulnerability of Singapore

In 1936, Major-General William Dobbie, then General Officer Commanding (Malaya), made an inquiry into whether more forces were required on mainland Malaya to prevent the Japanese from establishing forward bases to attack Singapore. Percival, then his Chief Staff Officer, was tasked to draw up a tactical assessment of how the Japanese were most likely to attack. In late 1937, his analysis duly confirmed that north Malaya might become the critical battleground. The Japanese were likely to seize the east coast landing sites on Thailand and Malaya in order to capture aerodromes and achieve air superiority. This could serve as a prelude to further Japanese landings in Johore to disrupt communications northwards and enable the construction of another main base in North Borneo. From North Borneo, the final sea and air assault could be launched against eastern Singapore—against Changi area.[50]

General Officer Commanding (Malaya)

In April 1941 Percival was promoted to acting lieutenant-general,[51] and was appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) Malaya. This was a significant promotion for him as he had never commanded an army Corps. He left Britain in a Sunderland flying boat and embarked on an arduous two-week, multi-stage flight via Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria (where he was delayed by the Anglo-Iraqi War), Basra, Karachi and Rangoon, where he was met by an RAF transport.[43]

Percival had mixed feelings about his appointment, noting that "In going to Malaya I realised that there was the double danger either of being left in an inactive command for some years if war did not break out in the East or, if it did, of finding myself involved in a pretty sticky business with the inadequate forces which are usually to be found in the distant parts of our Empire in the early stages of a war."[48]

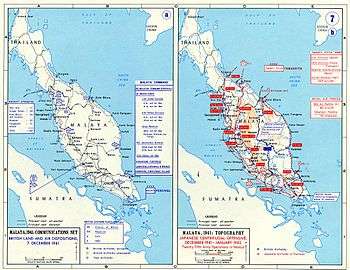

For much of the interwar period, Britain's defensive plan for Malaya had centred on the dispatch of a naval fleet to the newly built Singapore Naval Base. Accordingly, the army's role was to defend Singapore and Southern Johore. While this plan had seemed adequate when the nearest Japanese base had been 1,700 miles (2,700 km) away, the outbreak of war in Europe, combined with the partial Japanese occupation of the northern part of French Indochina and the signing of the Tripartite Pact in September 1940, had underlined the difficulty of a sea-based defence. Instead it was proposed to use the RAF to defend Malaya, at least until reinforcements could be dispatched from Britain. This led to the building of airfields in northern Malaya and along its east coast and the dispersal of the available army units around the peninsula to protect them.[52]

On arrival, Percival set about training his inexperienced army; his Indian troops were particularly raw, with most of their experienced officers having been withdrawn to support the formation of new units as the Indian army expanded. Relying upon commercial aircraft or the Volunteer air force to overcome the shortage of RAF planes, he toured the peninsula and encouraged the building of defensive works around Jitra.[53] A training manual approved by Percival, Tactical Notes on Malaya, was distributed to all units.

In July 1941 when the Japanese occupied southern Indochina, Britain, the United States and the Netherlands imposed economic sanctions, freezing Japanese financial assets and cutting Japan from its supplies of oil, tin and rubber. The sanctions were aimed at pressuring Japan to abandon its involvement in China; instead, the Japanese government planned to seize the resources of South-East Asia from the European nations by force. Both the Japanese navy and army were mobilised, but for the moment an uneasy state of cold war persisted. British Commonwealth reinforcements continued to trickle into Malaya. On 2 December, the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battle-cruiser HMS Repulse, escorted by four destroyers, arrived in Singapore, the first time a battle fleet had been based there. (They were to have been accompanied by the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable to provide air cover but she had run aground in the Caribbean en route.) The following day Rear-Admiral Spooner hosted a dinner attended by the newly arrived Commander-in-Chief Eastern Fleet, Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, and Percival.[54]

Japanese attack and British surrender

On 8 December 1941 the Japanese 25th Army under the command of Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita launched an amphibious assault on the Malay Peninsula (one hour before the attack on Pearl Harbor; the difference in date was because the two places lie on opposite sides of the international date line). That night the first Japanese invasion force arrived at Kota Bharu on Malaya's east coast. This was just a diversionary force, and the main landings took place the next day at Singora and Pattani on the south-eastern coast of Thailand, with troops rapidly deploying over the border into northern Malaya.

On 10 December Percival issued a stirring, if ultimately ineffective, Special Order of the Day:

In this hour of trial the General Officer Commanding calls upon all ranks Malaya Command for a determined and sustained effort to safeguard Malaya and the adjoining British territories. The eyes of the Empire are upon us. Our whole position in the Far East is at stake. The struggle may be long and grim but let us all resolve to stand fast come what may and to prove ourselves worthy of the great trust which has been placed in us.[55]

The Japanese advanced rapidly, and on 27 January 1942 Percival ordered a general retreat across the Johore Strait to the island of Singapore and organised a defence along the length of the island's 70-mile (110 km) coast line. But the Japanese did not dawdle, and on 8 February Japanese troops landed on the northwest corner of Singapore island. After a week of fighting on the island, Percival held his final command conference at 9 am on 15 February in the Battle Box of Fort Canning. The Japanese had already occupied approximately half of Singapore and it was clear that the island would soon fall. Having been told that ammunition and water would both run out by the following day, Percival agreed to surrender. The Japanese at this point were running low on artillery shells, but Percival did not know this.

The Japanese insisted that Percival himself march under a white flag to the Old Ford Motor Factory in Bukit Timah to negotiate the surrender. A Japanese officer present noted that he looked "pale, thin and tired".[56] After a brief disagreement, when Percival insisted that the British keep 1,000 men under arms in Singapore to preserve order, which Yamashita finally conceded, it was agreed at 6:10 pm that the British Empire troops would lay down their arms and cease resistance at 8:30 pm. This was in spite of instructions from Prime Minister Winston Churchill for prolonged resistance.[2] The Pacific War was just ten weeks old.

A common view holds that 138,708 Allied personnel surrendered or were killed by fewer than 30,000 Japanese. However, the former figure includes nearly 50,000 troops captured or killed during the Battle of Malaya, and perhaps 15,000 base troops. Many of the other troops were tired and under-equipped following their retreat from the Malayan peninsula. Conversely, the latter number represents only the front-line troops available for the invasion of Singapore. British Empire battle casualties since 8 December amounted to 7,500 killed and 11,000 wounded. Japanese losses totalled around 3,500 killed and 6,100 wounded.[57]

Culpability for the fall of Singapore

Churchill viewed the fall of Singapore to be "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history." However, the British defence was that the Middle East and the Soviet Union had all received higher priorities in the allocation of men and material, so the desired air force strength of 300 to 500 aircraft was never reached, and whereas the Japanese invaded with over two hundred tanks, the British Army in Malaya did not have a single tank.[58] In The War in Malaya Percival himself cites this as the major factor for the defeat stating that the 'war material which might have saved Singapore was sent to Russia and the Middle East'. However he also concedes that Britain was engaged in 'a life and death struggle in the West' and that 'this decision, however painful and regrettable, was inevitable and right'.[59]

In 1918, Percival had been described as "a slim, soft spoken man... with a proven reputation for bravery and organisational powers"[60] but by 1945 this description had been turned on its head with even Percival's defenders describing him as "something of a damp squib".[61] The fall of Singapore switched Percival's reputation to that of an ineffective "staff wallah", lacking ruthlessness and aggression, even though few doubted that he was a brave and determined officer. Over six feet in height and lanky, with a clipped moustache and two protruding teeth, and unphotogenic, Percival was an easy target for a caricaturist, being described as "tall, bucktoothed and lightly built".[62] There was no doubt his presentation lacked impact as "his manner was low key and he was a poor public speaker with the cusp of a lisp".[63]

It has been argued that Percival's colleagues bear a share of the responsibility of defeat. Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command, refused Percival permission to launch Operation Matador in advance of the Japanese landings in Thailand, not wishing to run any risk of provoking the coming war. Brooke-Popham also had a reputation for falling asleep in meetings and not arguing forcefully for the air reinforcements required to defend Malaya. Admiral Tom Phillips' leadership of Force Z led to his demise and the destruction of the British fleet on 10 December 1941, early in the campaign.

Peter Wykeham suggested that the government in London was more to blame than any of the British commanders in the Far East. Despite repeated requests, the British government did not provide the necessary reinforcements and they denied Brooke-Popham – and therefore Percival – permission to enter neutral Thailand before it was too late to put in place forward defences.[64]

Moreover, Percival had difficulties with his subordinates Sir Lewis "Piggy" Heath, commanding Indian III Corps, and the independent-minded Gordon Bennett, commanding the Australian 8th Division. The former officer had been senior to Percival prior to his appointment as GOC (Malaya). Bennett was full of confidence in his Australian troops and his own ability, but faced a mixed reaction in Australia when he escaped from Singapore immediately after its surrender.

Percival was ultimately responsible for the men who served under him, and with other officers – notably Major-General David Murray-Lyon, commander of the Indian 11th Infantry Division – he had shown a willingness to replace them when he felt their performance was not up to scratch. Perhaps his greatest mistake was to resist the building of fixed defences in either Johore or the north shore of Singapore, dismissing them in the face of repeated requests to start construction from his Chief Engineer, Brigadier Ivan Simson, with the comment "Defences are bad for morale – for both troops and civilians".[65] In doing so, Percival threw away the potential advantages he could have derived from the 6,000 engineers under his command and perhaps missed his best chance to blunt the danger posed by the Japanese tanks.

Percival also insisted on defending the north-eastern shore of Singapore most heavily, against the advice of the Allied supreme commander in South East Asia, General Archibald Wavell. Percival was perhaps fixed on his responsibilities for defending the Singapore Naval Base.[66] He also spread his forces thinly around the island and kept few units as a strategic reserve. When the Japanese attack came in the west, the Australian 22nd Brigade took the brunt of the assault.[67] Percival refused to reinforce them as he continued to believe that the main assault would occur in the north east.[68]

Captivity

Percival himself was briefly held prisoner in Changi Prison, where "the defeated GOC could be seen sitting head in hands, outside the married quarters he now shared with seven brigadiers, a colonel, his ADC and cook-sergeant. He discussed feelings with few, spent hours walking around the extensive compound, ruminating on the reverse and what might have been".[69] In the belief that it would improve discipline, he reconstituted a Malaya Command, complete with staff appointments, and helped occupy his fellow prisoners with lectures on the Battle of France.[70]

Along with the other senior British captives above the rank of colonel, Percival was removed from Singapore in August 1942. First he was imprisoned in Formosa and then sent on to Manchuria, where he was held with several dozen other VIP captives, including the American general Jonathan Wainwright, in a prisoner-of-war camp near Hsian, about 100 miles (160 km) to the north east of Mukden.

As the war drew to an end, an OSS team removed the prisoners from Hsian. Percival was then taken, along with Wainwright, to stand immediately behind General Douglas MacArthur as he confirmed the terms of the Japanese surrender aboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945.[71] Afterwards, MacArthur gave Percival a pen he had used to sign the treaty.[72]

Percival and Wainwright then returned together to the Philippines to witness the forced surrender of the Japanese army there, which in a twist of fate was commanded by General Yamashita. Yamashita was momentarily surprised to see his former captive at the ceremony; on this occasion Percival refused to shake Yamashita's hand, angered by the mistreatment of POWs in Singapore. The flag carried by Percival's party on the way to Bukit Timah was also a witness to this reversal of fortunes, being flown when the Japanese formally surrendered Singapore back to Lord Louis Mountbatten.[73]

Later life

Percival returned to the United Kingdom in September 1945 to write his despatch at the War Office but this was revised by the UK Government and only published in 1948.[74] He retired from the army in 1946 with the honorary rank of lieutenant-general but the pension of his substantive rank of major-general.[75] Thereafter, he held appointments connected with the county of Hertfordshire, where he lived at Bullards in Widford: he was Honorary Colonel of 479th (Hertfordshire Yeomanry) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, (T.A.) from 1949 to 1954[76][77] and acted as one of the Deputy Lieutenants of Hertfordshire in 1951.[78] He continued his relationship with the Cheshire Regiment being appointed Colonel of the Cheshire Regiment between 1950 and 1955;[79][80] an association continued by his son, Brigadier James Percival who became Colonel of the Regiment between 1992 and 1999.

While General Wainwright had become a public hero on his return to the United States, Percival found himself disparaged for his leadership in Malaya, even by Lieutenant-General Heath, his erstwhile subordinate. Percival's 1949 memoir, The War in Malaya, did little to quell this criticism, being a restrained rather than self-serving account of the campaign. Unusual for a British lieutenant-general, Percival was not awarded a knighthood.

Percival was respected for the time he had spent as a Japanese prisoner of war. Serving as life president of the Far East Prisoners of War Association (FEPOW), he pushed for compensation for his fellow captives, eventually helping to obtain a token £5 million of frozen Japanese assets for this cause. This was distributed by the FEPOW Welfare Trust, on which Percival served as Chairman.[81] He led protests against the film The Bridge on the River Kwai when it was released in 1957, obtaining the addition of an on-screen statement that the movie was a work of fiction. He also worked as President of the Hertfordshire British Red Cross and was made an Officer of the Venerable Order of Saint John in 1964.[82]

Percival died at the age of 78 on 31 January 1966, in King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers, Beaumont Street in Westminster, and was buried in Hertfordshire. Leonard Wilson, formerly the Bishop of Singapore, gave the address at his memorial service, which was held in St Martin-in-the-Fields.

Family

On 27 July 1927 Percival married Margaret Elizabeth "Betty" MacGregor (who died in 1956) in Holy Trinity Church, Brompton. She was the daughter of Thomas MacGregor Greer of Tallylagan Manor, a Protestant linen merchant from County Tyrone in Northern Ireland. They had met during his tour of duty in Ireland and it had taken Percival several years to propose. They had two children. A daughter, Dorinda Margery, was born in Greenwich and became Lady Dunleath. Alfred James MacGregor, their son, was born in Singapore and also served in the British Army.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arthur Ernest Percival. |

References

Bibliography

- Barry, Tom, Guerilla Days in Ireland, Dublin, 1949

- Bose, Romen, "SECRETS OF THE BATTLEBOX: The role and history of Britain's Command HQ during the Malayan Campaign", Marshall Cavendish, Singapore, 2005

- Coogan, Tim Pat. "Michael Collins". ISBN 0-09-968580-9

- Dixon, Norman F, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, London, 1976

- Hack, Karl and Blackburn, Kevin, Did Singapore Have to Fall?: Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress, RoutledgeCurzon, 2003, ISBN 0-415-30803-8

- Keegan, John (editor), Churchill's Generals, Abacus History, 1999, ISBN 0-349-11317-3

- Kinvig, Clifford, General Percival and the Fall of Singapore, in 60 Years On: the Fall of Singapore Revisited, Eastern University Press, Singapore, 2003

- Kinvig, Clifford, Scapegoat: General Percival of Singapore, London, 1996. ISBN 0-241-10583-8

- London Gazette

- MacArthur, Brian, Surviving the Sword: Prisoners of the Japanese 1942–45, Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11937-6

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 43, available at Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website

- Morris, James Farewell the Trumpets, Penguin Books, 1979

- Percival, Arthur Ernest The War in Malaya, London, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1949. Extracts from the report used as the basis of this book are at accessed 2 February 2006 and the references here are to this report

- Ryan, Meda. Tom Barry: IRA Freedom Fighter, Cork, 2003

- Smith, Colin, Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-101036-3

- Smyth, John George, Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore, MacDonald and Company, 1971. ASIN B0006CDC1Q

- Taylor, A. J. P. English History 1914–1945, Oxford University Press, 1975

- Thompson, Peter, The Battle for Singapore, London, 2005, ISBN 0-7499-5068-4 HB

- Warren, Alan, Singapore 1942: Britain's Greatest Defeat, Hambledon Continuum, 2001, ISBN 1-85285-328-X

External links

Notes

- ↑ Taylor, English History 1914–1945, p657

- 1 2 Morris, Farewell the Trumpets, p452

- ↑ Smyth, Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore

- 1 2 "British Army officer histories". Unit Histories. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ↑ Kinvig, Scapegoat: General Percival of Singapore, p5

- ↑ Smith, Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II, p23

- 1 2 "No. 29058". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 February 1915. pp. 1176–1179.

- ↑ "No. 29050". The London Gazette. 26 January 1915. p. 802.

- ↑ "No. 29824". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 November 1916. pp. 11044–11063.

- ↑ "No. 29783". The London Gazette. 13 October 1916. p. 9864.

- ↑ "No. 30038". The London Gazette (Supplement). 27 April 1917. p. 4042.

- ↑ "No. 30632". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 April 1918. p. 4550.

- ↑ "No. 31003". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 November 1918. p. 13282.

- ↑ "No. 31035". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 November 1918. p. 14044.

- ↑ "No. 31220". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 March 1919. p. 3257.

- ↑ "No. 32233". The London Gazette (Supplement). 18 February 1921. p. 1434.

- ↑ Smith, p24

- ↑ "No. 31092". The London Gazette (Supplement). 24 June 1921. pp. 15–16.

- ↑ "No. 32371". The London Gazette (Supplement). 24 June 1921. p. 5096.

- ↑ Keegan, Churchill's Generals, p257

- ↑ "No. 31745". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 January 1920. p. 923.

- ↑ "Essex Regiment". National Army Museum. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Thompson, The Battle for Singapore, p. 69.

- ↑ Statement by witness Patrick O'Brien, Bureau of Military History, http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/r%5B%5D ... WS0812.pdf

- ↑ John Burns, 'Tom Barry "lied about massacre"', Sunday Times (19 April 1998).

- ↑ Michael Collins, Tim Pat Coogan page 146

- ↑ Irish Independent 5/6/1922.

- ↑ Kivnig;Scapegoat

- ↑ Narratives; British Intelligence in Ireland 1920-21-The Final Reports edited by Peter Hart page 82 ISBN 1-85918201-1

- ↑ A Winter's Tale by Sir Ormonde Winter page 300

- ↑ Thompson, The Battle for Singapore, p69–70

- ↑ Sheehan, William (2005). British Voices from the Irish War of Independence 1918–1921: the words of British servicemen who were there. Collins Press, p. 167. ISBN 1903464897

- ↑ "No. 32790". The London Gazette. 26 January 1923. p. 608.

- ↑ "No. 33043". The London Gazette. 1 May 1925. p. 2921.

- ↑ "No. 33470". The London Gazette. 26 February 1929. p. 1345.

- ↑ "No. 33454". The London Gazette. 4 January 1929. p. 152.

- ↑ Thompson, p71

- ↑ "No. 33846". The London Gazette. 15 July 1932. p. 4627.

- ↑ "No. 34264". The London Gazette. 13 March 1936. p. 1657.

- ↑ "No. 34557". The London Gazette. 30 September 1938. pp. 6139–6140.

- ↑ Hack and Blackburn, Did Singapore Have to Fall?: Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress, p39

- ↑ Kinvig, p106

- 1 2 Percival, The War in Malaya, Chapter 1

- ↑ "No. 34503". The London Gazette. 19 April 1938. p. 2594.

- ↑ "No. 34800". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 February 1940. p. 1151.

- ↑ "No. 34855". The London Gazette (Supplement). 21 May 1940. p. 3091.

- ↑ "No. 34895". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 July 1940. p. 4273.

- 1 2 Percival, Chapter 2

- ↑ "No. 35204". The London Gazette (Supplement). 27 June 1941. pp. 3735–3736.

- ↑ Ong, Chit Chung (1997) Operation Matador : Britain's war plans against the Japanese 1918–1941. Singapore : Times Academic Press.

- ↑ "No. 35160". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 May 1941. p. 2731.

- ↑ Percival, Chapter 3

- ↑ Percival, Chapter 4

- ↑ Percival, Chapter 7

- ↑ Percival, chapter 9

- ↑ Warren, p265

- ↑ Thompson, p9 and p424

- ↑ Kinvig.

- ↑ The War in Malaya; Authur Percival p306

- ↑ Kinvig, p. 47.

- ↑ Kinvig, p. 242.

- ↑ Warren, p. 29.

- ↑ Kinvig, General Percival and the Fall of Singapore, p. 241.

- ↑ Wykeham, Peter; Thomas Paul Ofcansky (January 2008). "Popham, Sir (Henry) Robert Moore Brooke". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32096.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 182.

- ↑ Dixon, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, p. 143.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 414.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 430.

- ↑ Kinvig, p221

- ↑ MacArthur, Surviving the Sword: Prisoners of the Japanese 1942–45, p188

- ↑ Battleship Missouri Memorial, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 November 2005. Retrieved 2006-02-02. , accessed 2 February 2006

- ↑ Warren, p286

- ↑ Morris, p458

- ↑ "No. 38215". The London Gazette. 20 February 1948. pp. 1245–1346.

- ↑ "No. 37706". The London Gazette. 27 August 1946. p. 4347.

- ↑ "No. 38762". The London Gazette. 18 November 1949. p. 5465.

- ↑ Col J.D. Sainsbury, The Hertfordshire Yeomanry Regiments, Royal Artillery, Part 2: The Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment 1938–1945 and the Searchlight Battery 1937–1945; Part 3: The Post-war Units 1947–2002, Welwyn: Hertfordshire Yeomanry and Artillery Trust/Hart Books, 2003, ISBN 0-948527-06-4.

- ↑ "No. 39412". The London Gazette. 18 December 1951. p. 6600.

- ↑ "No. 38940". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1950. p. 3037.

- ↑ "No. 40680". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 January 1956. p. 208.

- ↑ MacArthur, p. 442.

- ↑ "No. 43367". The London Gazette. 26 June 1964. pp. 5540–5542.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arthur Floyer-Acland |

GOC 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division February – April 1940 |

Succeeded by Robert Pollok |

| Preceded by Edmund Osborne |

GOC 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division 1940–1941 |

Succeeded by Noel Mason-MacFarlane |

| Preceded by Sir Lionel Bond |

GOC Malaya Command 1941–1942 |

Succeeded by Fell to Japan |