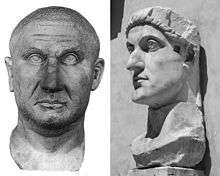

Licinius

| Licinius | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58th Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

Coin of Licinius | |||||

| Reign |

11 November 308 – 311 (as Augustus in the west, with Galerius in the east); 311–313 (Augustus in the west, with Maximinus in the east) 313–324 (Augustus in the east, with Constantine in the west – in 314 and 324 in competition with him) | ||||

| Predecessor | Severus | ||||

| Successor | Constantine I | ||||

| Born |

c. 263[1] Moesia Superior, near Zaječar in modern-day Serbia | ||||

| Died |

Spring of 325 (aged 61-62) Thessalonica | ||||

| Wife | |||||

| Issue | Licinius II | ||||

| |||||

Licinius I (Latin: Gaius Valerius Licinianus Licinius Augustus;[note 1][2][3] c. 263–325) was a Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan that granted official toleration to Christians in the Roman Empire. He was finally defeated at the Battle of Chrysopolis, before being executed on the orders of Constantine I.

Early reign

Born to a Dacian[4][5] peasant family in Moesia Superior, Licinius accompanied his close childhood friend, the future emperor Galerius, on the Persian expedition in 298.[4] He was trusted enough by Galerius that in 307 he was sent as an envoy to Maxentius in Italy to attempt to reach some agreement about the latter's illegitimate political position.[4] Galerius then trusted the eastern provinces to Licinius when he went to deal with Maxentius personally after the death of Flavius Valerius Severus.[6]

Upon his return to the east Galerius elevated Licinius to the rank of Augustus in the West on November 11, 308. He received as his immediate command the provinces of Illyricum, Thrace and Pannonia.[5] In 310 he took command of the war against the Sarmatians, inflicting a severe defeat on them and emerging victorious.[2] On the death of Galerius in May 311, Licinius entered into an agreement with Maximinus II (Daia) to share the eastern provinces between them. By this point, not only was Licinius the official Augustus of the west but he also possessed part of the eastern provinces as well, as the Hellespont and the Bosporus became the dividing line, with Licinius taking the European provinces and Maximinus taking the Asian.[5]

An alliance between Maximinus and Maxentius forced the two remaining emperors to enter into a formal agreement with each other.[6] So in March 313 Licinius married Flavia Julia Constantia, half-sister of Constantine I,[3] at Mediolanum (now Milan); they had a son, Licinius the Younger, in 315. Their marriage was the occasion for the jointly-issued "Edict of Milan" that reissued Galerius' previous edict allowing Christianity to be professed in the Empire,[5] with additional dispositions that restored confiscated properties to Christian congregations and exempted Christian clergy from municipal civic duties.[7] The redaction of the edict as reproduced by Lactantius - who follows the text affixed by Licinius in Nicomedia on June 14 313, after Maximinus' defeat - uses a neutral language, expressing a will to propitiate "any Divinity whatsoever in the seat of the heavens".[8]

Daia in the meantime decided to attack Licinius. Leaving Syria with 70,000 men, he reached Bithynia, although harsh weather he encountered along the way had gravely weakened his army. In April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and went to Byzantium, which was held by Licinius' troops. Undeterred, he took the town after an eleven-day siege. He moved to Heraclea, which he captured after a short siege, before moving his forces to the first posting station. With a much smaller body of men, possibly around 30,000,[9] Licinius arrived at Adrianople while Daia was still besieging Heraclea. Before the decisive engagement, Licinius allegedly had a vision in which an angel recited him a generic prayer that could be adopted by all cults and which Licinius then repeated to his soldiers.[10] On 30 April 313, the two armies clashed at the Battle of Tzirallum, and in the ensuing battle Daia's forces were crushed. Ridding himself of the imperial purple and dressing like a slave, Daia fled to Nicomedia.[6] Believing he still had a chance to come out victorious, Daia attempted to stop the advance of Licinius at the Cilician Gates by establishing fortifications there. Unfortunately for Daia, Licinius' army succeeded in breaking through, forcing Daia to retreat to Tarsus where Licinius continued to press him on land and sea. The war between them only ended with Daia’s death in August 313.[5]

Given that Constantine had already crushed his rival Maxentius in 312, the two men decided to divide the Roman world between them. As a result of this settlement, Licinius became sole Augustus in the East, while his brother-in-law, Constantine, was supreme in the West. Licinius immediately rushed to the east to deal with another threat, this time from the Persian Sassanids.[6]

Conflict with Constantine I

In 314, a civil war erupted between Licinius and Constantine, in which Constantine used the pretext that Licinius was harbouring Senecio, whom Constantine accused of plotting to overthrow him.[6] Constantine prevailed at the Battle of Cibalae in Pannonia (October 8, 314).[5] Although the situation was temporarily settled, with both men sharing the consulship in 315, it was but a lull in the storm. The next year a new war erupted, when Licinius named Valerius Valens co-emperor,[3] only for Licinius to suffer a humiliating defeat on the plain of Mardia (also known as Campus Ardiensis) in Thrace. The emperors were reconciled after these two battles and Licinius had his co-emperor Valens killed.[5]

Over the next ten years, the two imperial colleagues maintained an uneasy truce.[6] Licinius kept himself busy with a campaign against the Sarmatians in 318,[5] but temperatures rose again in 321 when Constantine pursued some Sarmatians, who had been ravaging some territory in his realm, across the Danube into what was technically Licinius’s territory.[5] When he repeated this with another invasion, this time by the Goths who were pillaging Thrace, Licinius complained that Constantine had broken the treaty between them.

Constantine wasted no time going on the offensive. Licinius's fleet of 350 ships was defeated by Constantine's fleet in 323. Then in 324, Constantine, tempted by the "advanced age and unpopular vices"[6] of his colleague, again declared war against him and having defeated his army of 170,000 men at the Battle of Adrianople (July 3, 324), succeeded in shutting him up within the walls of Byzantium.[5] The defeat of the superior fleet of Licinius in the Battle of the Hellespont by Crispus, Constantine’s eldest son and Caesar, compelled his withdrawal to Bithynia, where a last stand was made; the Battle of Chrysopolis, near Chalcedon (September 18), resulted in Licinius' final submission.[6] While Licinius' co-emperor Sextus Martinianus was killed, Licinius himself was spared due to the pleas of his wife, Constantine's sister and interned at Thessalonica.[3] The next year, Constantine had him hanged, accusing him of conspiring to raise troops among the barbarians.[6]

Character and legacy

_obverse.jpg)

After defeating Daia, he had put to death Flavius Severianus, the son of the emperor Severus, as well as Candidianus, the son of Galerius.[6] He also ordered the execution of the wife and daughter of the Emperor Diocletian, who had fled from the court of Licinius before being discovered at Thessalonica.[6]

As part of Constantine’s attempts to decrease Licinius’s popularity, he actively portrayed his brother-in-law as a pagan supporter. This was not the case; contemporary evidence tends to suggest that he was at least a committed supporter of Christians.[3] He co-authored the Edict of Milan which ended the Great Persecution, and re-affirmed the rights of Christians in his half of the empire. He also added the Christian symbol to his armies, and attempted to regulate the affairs of the Church hierarchy just as Constantine and his successors were to do. His wife was a devout Christian.[11] It is even a possibility that he converted.[3] However, Eusebius of Caesarea, writing under the rule of Constantine, charges him with expelling Christians from the Palace and ordering military sacrifice, as well as interfering with the Church's internal procedures and organization.[12] According to Eusebius, this turned what appeared to be a committed Christian into a man who feigned sympathy for the sect but who eventually exposed his true bloodthirsty pagan nature, only to be stopped by the virtuous Constantine.[3]

Finally, on Licinius’s death, his memory was branded with infamy; his statues were thrown down; and by edict, all his laws and judicial proceedings during his reign were abolished.[6]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In Classical Latin, Licinius' name would be inscribed as GAIVS VALERIVS LICINIANVS LICINIVS AVGVSTVS.

References and sources

- References

- ↑ Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy (1998). Handbook to life in ancient Rome. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-19-512332-8.

- 1 2 Lendering, Jona. "Licinius". Livius.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Canduci, Alexander (2010). Triumph & Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome's Immortal Emperors. Pier 9. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-74196-598-8.

- 1 2 3 Jones, A.H.M.; Martindale, J.R. (1971). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. I: AD260-395. Cambridge University Press. p. 509.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 DiMaio, Michael, Jr. (February 23, 1997). "Licinius (308–324 A.D.)". De Imperatoribus Romanis.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gibbon, Edward (1776). "Chapter XIV". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. II.

- ↑ Carrié, Jean-Michel; Rousselle, Aline (1999). L'Empire Romain en mutation: des Sévères à Constantin, 192-337. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. p. 228. ISBN 2-02-025819-6.

- ↑ Lactantius, De Mort. Pers., ch. 48, cf. Internet History Sourcebooks Project, Fordham University, . Accessed July 31, 2012

- ↑ Kohn, George Childs, Dictionary Of Wars, Revised Edition, pg 398.

- ↑ Carrié & Rousselle, L'Empire Romain en Mutation, 229

- ↑ Peter J. Leithart, Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom. Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL: 2010, ISBN 978-0-8308-2722-0, page 101

- ↑ James Richard Gearey, "The Persecution of Licinius". MA thesis, University of Calgary, 1999, Chapter 4. Available at . Accessed July 31, 2012.

- Sources

- Pears, Edwin. “The Campaign against Paganism A.D. 324.” The English Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 93 (January 1909): 1–17.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Licinius". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 587.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Licinius". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 587.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Licinius. |

- De Imperatoribus Romanis: Licinius

- Socrates Scholasticus account of Licinius' end

- Roman and Greek Coins