Lichen sclerosus

| Lichen sclerosus | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | balanitis xerotica obliterans, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus,[1] lichen plan atrophique, lichen plan scléreux, Kartenblattförmige Sklerodermie, Weissflecken Dermatose, lichen albus, lichen planus sclerosus et atrophicus, dermatitis lichenoides chronica atrophicans, kraurosis vulvae[2] |

| |

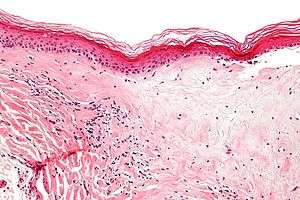

| Micrograph of lichen sclerosus showing the characteristic subepithelial sclerosus (right/bottom of image). H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | dermatology |

| ICD-10 | L90.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 701.0 |

| eMedicine | derm/234 |

| MeSH | D018459 |

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a skin disease of unknown cause, commonly appearing as whitish patches on the genitals, which can affect any body part of any person but has a strong preference for the genitals (penis, vulva) and is also known as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO) when it affects the penis. Lichen sclerosus is not contagious. There is a well-documented increase of skin cancer risk in LS, potentially improvable with treatment. LS in adult age is normally incurable, but improvable with treatment, and often gets progressively worse.

Signs and symptoms

LS can occur without symptoms. White patches on the LS body area, itching, pain, pain during sex (in genital LS), easier bruising, cracking, tearing and peeling, and hyperkeratosis are common symptoms in both men and women. In women, the condition most commonly occurs on the vulva and around the anus with ivory-white elevations that may be flat and glistening.

In males, the disease may take the form of whitish patches on the foreskin and its narrowing (preputial stenosis), forming an "indurated ring", which can make retraction more difficult or impossible. In addition there can be lesions, white patches or reddening on the glans. In contrast to women, anal involvement is less frequent. Meatal stenosis, making it more difficult or even impossible to urinate, may also occur.

On the non-genital skin, the disease may manifest as porcelain-white spots with small visible plugs inside the orifices of hair follicles or sweat glands on the surface. Thinning of the skin may also occur.[3]

Diagnosis

The disease often goes undiagnosed for several years, as it is sometimes not recognized and misdiagnosed as thrush or other problems and not correctly diagnosed until the patient is referred to a specialist when the problem does not clear up.

A biopsy of the affected skin can be done to confirm diagnosis. When a biopsy is done, hyperkeratosis, atrophic epidermis, sclerosis of dermis and lymphocyte activity in dermis are histological findings associated with LS.[4] The biopsies are also checked for signs of dysplasia.[5]

It has been noted that clinical diagnosis of LS can be "almost unmistakable" and therefore a biopsy may not be necessary.[6]

Treatment

Main treatment

There is no definitive cure for LS.[7] Behavior change is part of treatment. The patient should minimize or preferably stop scratching LS-affected skin.[8] Any scratching, stress or damage to the skin can worsen the disease. Scratching has been theorized to increase cancer risks.[9] Furthermore the patient should wear comfortable clothes and avoid tight clothing, as it is a major factor in the severity of symptoms in some cases.[9][10]

Topically applied corticosteroids to the LS-affected skin are the first-line treatment for lichen sclerosus in women and men, with strong evidence showing that they are "safe and effective" when appropriately applied, even over long courses of treatment, rarely causing serious adverse effects.[11][12][13][14][15] They improve or suppress all symptoms for some time, which highly varies across patients, until it is required to use them again.[16] Methylprednisolone aceponate has been used as a safe and effective corticosteroid for mild and moderate cases.[17] For severe cases, it has been theorized that mometasone furoate might be safer and more effective than clobetasol.[17]

Continuous usage of appropriate doses of topical corticosteroids is required to ensure symptoms stay relieved over the patient's life time. If continuously used, corticosteroids have been suggested to minimize the risk of cancer in various studies. In a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 507 women throughout 6 years, cancer occurred for 4.7% of patients who were only "partially compliant" with corticosteroid treatment, while it occurred in 0% of cases where they were "fully compliant".[18] In a second study, of 129 patients, cancer occurred in 11% of patients, none of which were fully compliant with corticosteroid treatment.[17] Both these studies however also said that a corticosteroid as powerful as clobetasol isn't necessary in most cases. In a prospective study of 83 patients, throughout 20 years, 8 patients developed cancer. 6 already had cancer at presentation and had not had treatment, while the other 2 weren't taking corticosteroids often enough.[16] In all three studies, every single cancer case observed occurred in patients who weren't taking corticosteroids as often as the study recommended.

Continuous, abundant usage of emollients topically applied to the LS-affected skin is recommended to improve symptoms. They can supplement but not replace corticosteroid therapy.[14][19][12] They can be used much more frequently than corticosteroids due to the extreme rarity of serious adverse effects. Appropriate lubrication should be used every time before and during sex in genital LS in order to avoid pain and worsening the disease.[20] Some oils such as olive oil and coconut oil can be used to accomplish both the emollient and sexual lubrication function.

Recent studies have shown that topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus can have an effect similar to corticosteroids, but its effects on cancer risks in LS are not conclusively known.[21][22]

In males, it has been reported that circumcision can have positive effects, but does not necessarily prevent against further flares of the disease[23] and does not protect against the possibility of cancer.[24] Circumcision does not prevent or cure LS; in fact, "balanitis xerotica obliterans" in men was first reported as a condition affecting a set of circumcised men, by Stühmer in 1928.[2]

Other treatments

Carbon dioxide laser treatment is safe, effective and improves symptoms over a long time,[25] but does not lower cancer risks.

Platelet rich plasma was reported to be effective in one study, producing large improvements in the patients' quality of life, with an average IGA improvement of 2.04 and DLQI improvement of 7.73.[26]

Psychological effect

Distress due to the discomfort and pain of Lichen Sclerosus is normal, as are concerns with self-esteem and sex. Counseling can help.

According to the National Vulvodynia Association, which also supports women with Lichen Sclerosus, vulvo-vaginal conditions can cause feelings of isolation, hopelessness, low self-image, and much more. Some women are unable to continue working or have sexual relations and may be limited in other physical activities.[27] Depression, anxiety, and even anger are all normal responses to the ongoing pain LS patients suffer from.

Prognosis

The disease can last for a considerably long time. Occasionally, "spontaneous cure" may ensue,[28] particularly in young girls.

Lichen sclerosus is associated with a higher risk of cancer.[29][30][31] Skin that has been scarred as a result of lichen sclerosus is more likely to develop skin cancer. Women with lichen sclerosus may develop vulvar carcinoma.[32] Lichen sclerosus is associated with 3–7% of all cases of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma.[33] In women, it has been reported that 33.6 times higher vulvar cancer risk is associated with LS.[34] A study in men reported that "The reported incidence of penile carcinoma in patients with BXO is 2.6–5.8%".[35]

Pathophysiology

Although it is not clear what causes LS, several theories have been postulated. Lichen Sclerosus is not contagious; it cannot be caught from another person.[36]

Several risk factors have been proposed, including autoimmune diseases, infections and genetic predisposition.[37][38] There is evidence that LS can be associated with thyroid disease.[39]

Genetic

Lichen sclerosus may have a genetic component. Higher rates of lichen sclerosus have been reported among twins[40][41] and among family members.[42]

Autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is a process in which the body fails to recognize itself and therefore attacks its own cells and tissue. Specific antibodies have been found in LS. Furthermore, there seems to be a higher prevalence of other autoimmune diseases such as diabetes mellitus type 1, vitiligo and thyroid disease.[43]

Infection

Both bacterial as well as viral pathogens have been implicated in the etiology of LS. A disease that is similar to LS, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Viral involvement of HPV[44] and hepatitis C[45] are also suspected.

A link with Lyme Disease is shown by the presence of Borrelia burgdorferi in LSA biopsy tissue.[46]

Hormones

Since LS in females is primarily found in women with a low estrogen state (prepubertal and postmenopausal women), hormonal influences were postulated. To date though, very little evidence has been found to support this theory.

Local skin changes

Some findings suggest that LS can be initiated through scarring[47] or radiation,[48][49] although these findings were sporadic and very uncommon.

Epidemiology

There is a bimodal age distribution in the incidence of LS in women. It occurs in females with an average age of diagnosis of 7.6 years in girls and 60 years old in women. The average age of diagnosis in boys is 9–11 years old.[50]

In men, the most common age of incidence is 21-30.[51]

History

In 1875, Weir reported what was possible vulvar or oral LS as "ichthyosis". In 1885, Breisky described kraurosis vulvae. In 1887, Hallopeau describes series of extragenital LS. In 1892, Darier formally describes classic histopathology of LS. From 1900 to present, the concept starts being formed that scleroderma and LS are closely related. In 1901, Pediatric LS was described. From 1913 to present, the concept that scleroderma is not closely related to LS also starts being formed. In 1920, Taussig establishes vulvectomy as treatment of choice for kraurosis vulvae, a premalignant condition. In 1927, Kyrle defines LS ("white spot disease") as entity sui generis. In 1928, Stühmer describes balanitis xerotica obliterans as postcircumcision phenomenon. In 1936, Retinoids (vitamin A) used in LS. In 1945, Testosterone used in genital LS. In 1961, the use of corticosteroids started. In Jeffcoate presents argument against vulvectomy for simple LS. In 1971, Progesterone used in LS, Wallace defines clinical factors and epidemiology of LS for all later reports. In 1976, Friedrich defines LS as a dystrophic, not atrophic condition; "et atrophicus" dropped. International Society for Study of Vulvar Disease classification system. "Kraurosis" and "leukoplakia" no longer to be used. In 1980, Fluourinated and superpotent steroids used in LS. In 1981, studies into HLA serotypes and LS. In 1984, Etretinate and acetretin used in LS. In 1987, LS linked with Borrelia infection.[2]

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus was first described in 1887 by Dr. Hallopeau.[52] Since not all cases of lichen sclerosus exhibit atrophic tissue, et atrophicus was dropped in 1976 by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), officially proclaiming the name lichen sclerosus.[53]

See also

- Lichen planus

- List of cutaneous conditions

- List of cutaneous conditions associated with increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer

- List of human leukocyte antigen alleles associated with cutaneous conditions

References

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 227. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- 1 2 3 Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen Sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32(3): 393-416.

- ↑ Laymon, CW (1951). "Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and related disorders". MA Arch Derm Syphilol. 64 (5): 620–627. PMID 14867888. doi:10.1001/archderm.1951.01570110090013.

- ↑ Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus at eMedicine

- ↑ Shelley, W. B.; Shelley, E. D.; Amurao, C. V. (2006). "Treatment of lichen sclerosus with antibiotics". International Journal of Dermatology. 45 (9): 1104–1106. PMID 16961523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02978.x.

- ↑ Depasquale, I.; Park, A.J.; Bracka, A. (2000). "The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans". BJU International. 86 (4): 459–465. ISSN 1464-4096. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2000.00772.x.

- ↑ Chi, CC; Kirtschig, G; Baldo, M; Lewis, F; Wang, SH; Wojnarowska, F (Aug 2012). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on topical interventions for genital lichen sclerosus.". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 67 (2): 305–12. PMID 22483994. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.044.

- ↑ "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 93: diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders.". Obstet Gynecol. 111 (5): 1243–53. May 2008. PMID 18448767. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817578ba.

- 1 2 "Does lichen sclerosus play a central role in the pathogenesis of human papillomavirus negative vulvar squamous cell carcinoma? The itch-scratch-lichen sclerosus hypothesis." Scurry J, Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1999 Mar;9(2):89-97.

- ↑ Todd, P.; Halpern, S.; Kirby, J.; Pembroke, A. (1994). "Lichen sclerosus and the Kobner phenomenon". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 19 (3): 262–263. ISSN 0307-6938. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01183.x.

- ↑ Dalziel, K.L.; Millard, P.R.; Wojnarowska, F. (1991). "The treatment of vulval lichen sclerosus with a very potent topical steroid (clobetasol Propionate 0.05%) cream". British Journal of Dermatology. 124 (5): 461–464. ISSN 0007-0963. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb00626.x.

- 1 2 Garzon, Maria C.; Paller, Amy S. (1999). "Ultrapotent Topical Corticosteroid Treatment of Childhood Genital Lichen Sclerosus". Archives of Dermatology. 135 (5). ISSN 0003-987X. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.5.525.

- ↑ Dahlman-Ghozlan, Kristina; Hedblad, Mari-Anne; von Krogh, Geo (1999). "Penile lichen sclerosus et atrophicus treated with clobetasol dipropionate 0.05% cream: A retrospective clinical and histopathologic study". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 40 (3): 451–457. ISSN 0190-9622. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70496-2.

- 1 2 Neill, S.M.; Lewis, F.M.; Tatnall, F.M.; Cox, N.H. (2010). "British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus 2010". British Journal of Dermatology. 163 (4): 672–682. ISSN 0007-0963. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09997.x.

- ↑ Neill, S.M.; Tatnall, F.M.; Cox, N.H. (2002). "Guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus". British Journal of Dermatology. 147 (4): 640–649. ISSN 0007-0963. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.05012.x.

- 1 2 Renaud-Vilmer, Catherine; Cavelier-Balloy, Bénédicte; Porcher, Raphaël; Dubertret, Louis (2004). "Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus". Archives of Dermatology. 140 (6). ISSN 0003-987X. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.6.709.

- 1 2 3 Bradford, J.; Fischer, G. (2010). "Long-term management of vulval lichen sclerosus in adult women". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 50 (2): 148–152. ISSN 0004-8666. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01142.x.

- ↑ Lee, Andrew; Bradford, Jennifer; Fischer, Gayle (2015). "Long-term Management of Adult Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus". JAMA Dermatology. 151 (10): 1061. ISSN 2168-6068. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0643.

- ↑ Fistarol, Susanna K.; Itin, Peter H. (2012). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Lichen Sclerosus". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 14 (1): 27–47. ISSN 1175-0561. doi:10.1007/s40257-012-0006-4.

- ↑ Smith, Yolanda R; Haefner, Hope K (2004). "Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 5 (2): 105–125. ISSN 1175-0561. doi:10.2165/00128071-200405020-00005.

- ↑ Li, Y; Xiao, Y; Wang, H; Li, H; Luo, X (Aug 2013). "Low-concentration topical tacrolimus for the treatment of anogenital lichen sclerosus in childhood: maintenance treatment to reduce recurrence.". Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 26 (4): 239–42. PMID 24049806. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2012.11.010.

- ↑ Maassen, MS; van Doorn, HC (2012). "[Topical treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus with calcineurin inhibitors].". Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 156 (36): A3908. PMID 22951124.

- ↑ Neill SM, Tatnall FM, Cox NH. Guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:640-9.

- ↑ Powell, J.; Robson, A.; Cranston, D.; Wojnarowska, F.; Turner, R. (2001). "High incidence of lichen sclerosus in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the penis". British Journal of Dermatology. 145 (1): 85–89. ISSN 0007-0963. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04287.x.

- ↑ Windahl, T. (2009). "Is carbon dioxide laser treatment of lichen sclerosus effective in the long run?". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 40 (3): 208–211. ISSN 0036-5599. doi:10.1080/00365590600589666.

- ↑ Casabona, Francesco; Gambelli, Ilaria; Casabona, Federica; Santi, Pierluigi; Santori, Gregorio; Baldelli, Ilaria (2017). "Autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in chronic penile lichen sclerosus: the impact on tissue repair and patient quality of life". International Urology and Nephrology. 49 (4): 573–580. ISSN 0301-1623. doi:10.1007/s11255-017-1523-0.

- ↑ National Vulvodynia Association. "Vulvodynia Fact Sheet". Vulvodynia Media Corner. National Vulvodynia Association. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ↑ Smith SD, Fischer G (2009). "Childhood onset vulvar lichen sclerosus does not resolve at puberty: a prospective case series". Pediatr Dermatol. 26 (6): 725–9. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01022.x.

- ↑ Nasca, MR; Innocenzi, D; Micali, G (1999). "Penile cancer among patients with genital lichen sclerosus". J Am Acad Dermatol. 41 (6): 911–914. PMID 10570372. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70245-8.

- ↑ Poulsen, H; Junge, J; Vyberg, M; Horn, T; Lundvall, F (2003). "Small vulvar squamous cell carcinomas and adjacent tissues. A morphologic study". APMIS. 111 (9): 835–842. PMID 14510640. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0463.2003.1110901.x.

- ↑ Barbagli, G; Palminteri, E; Mirri, F; Guazzoni, G; Turini, D; Lazzeri, M (2006). "Penile carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus: a multicenter survey". J Urol. 175 (4): 1359–1363. PMID 16515998. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00735-4.

- ↑ van de Nieuwenhof, HP; van der Avoort, IA; de Hullu, JA (2008). "Review of squamous premalignant vulvar lesions". Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 68 (2): 131–156. PMID 18406622. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.012.

- ↑ Henquet, CJ (Aug 2011). "Anogenital malignancies and pre-malignancies.". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 25 (8): 885–95. PMID 21272092. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03969.x.

- ↑ Halonen, Pia; Jakobsson, Maija; Heikinheimo, Oskari; Riska, Annika; Gissler, Mika; Pukkala, Eero (2017). "Lichen sclerosus and risk of cancer". International Journal of Cancer. 140 (9): 1998–2002. ISSN 0020-7136. doi:10.1002/ijc.30621.

- ↑ Pietrzak, Peter; Hadway, Paul; Corbishley, Cathy M.; Watkin, Nicholas A. (2006). "Is the association between balanitis xerotica obliterans and penile carcinoma underestimated?". BJU International. 98 (1): 74–76. ISSN 1464-4096. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06213.x.

- ↑ National Institute of Health. "Fast Facts About Lichen Sclerosus". Lichen Sclerosus. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ↑ Yesudian, PD; Sugunendran, H; Bates, CM; O'Mahony, C (2005). "Lichen sclerosus". Int J STD AIDS. 16 (7): 465–473. PMID 16004624. doi:10.1258/0956462054308440.

- ↑ Regauer, S (2005). "Immune dysregulation in lichen sclerosus". Eur J Cell Biol. 84 (2–3): 273–277. PMID 15819407. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.003.

- ↑ Birenbaum, DL; Young, RC (2007). "High prevalence of thyroid disease in patients with lichen sclerosus". J Reprod Med. 52 (1): 28–30. PMID 17286064.

- ↑ Meyrick Thomas, RH; Kennedy, CT (Mar 1986). "The development of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in monozygotic twin girls.". The British journal of dermatology. 114 (3): 377–379. PMID 3954957. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb02831.x.

- ↑ Cox, NH; Mitchell, JN; Morley, WN (Dec 1986). "Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in non-identical female twins.". The British journal of dermatology. 115 (6): 743–746. PMID 3801314. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb06659.x.

- ↑ Sherman, V; McPherson, T; Baldo, M; Salim, A; Gao, XH; Wojnarowska, F (Sep 2010). "The high rate of familial lichen sclerosus suggests a genetic contribution: an observational cohort study.". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 24 (9): 1031–1034. PMID 20202060. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03572.x.

- ↑ Meyrick Thomas, RH; Ridley, CM; McGibbon, DH; Black, MM (1988). "Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity—a study of 350 women". Br J Dermatol. 118 (1): 41–46. PMID 3342175. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb01748.x.

- ↑ Drut, RM; Gomez, MA; Drut, R; Lojo, MM (1998). "Human papillomavirus is present in some cases of childhood penile lichen sclerosus: an in situ hybridization and SP-PCR study". Pediatr Dermatol. 15 (2): 85–90. PMID 9572688. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015085.x.

- ↑ Yashar, S; Han, KF; Haley, JC (2004). "Lichen sclerosus-lichen planus overlap in a patient with hepatitis C virus infection". Br J Dermatol. 150 (1): 168–169. PMID 14746647. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05707.x.

- ↑ Eisendle, K; Grabner, TG; Kutzner, H (2008). "Possible Role of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato Infection in Lichen Sclerosus". Br J Dermatol. 144 (5): 591–598. PMID 18490585. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.5.591.

- ↑ Pass, CJ (1984). "An unusual variant of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: delayed appearance in a surgical scar". Cutis. 33 (4): 405. PMID 6723373.

- ↑ Milligan, A; Graham-Brown, RA; Burns, DA (1988). "Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus following sunburn". Clin Exp Dermatol. 13 (1): 36–37. PMID 3208439.

- ↑ Yates, VM; King, CM; Dave, VK (1985). "Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus following radiation therapy". Arch Dermatol. 121 (8): 1044–1047. PMID 4026344. doi:10.1001/archderm.121.8.1044.

- ↑ Fistarol, Susanna K (2013). "Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update.". Journal of American Academy of Dermatology. 14 (1): 27–47. doi:10.1007/s40257-012-0006-4.

- ↑ Kizer WS, Prairie T, Morey AF. Balanitis xerotica obliterans: epidemiologic distribution in an equal access health care system. South Med J 2003;96(1):9-11

- ↑ Hallopeau, H (1887). "Du lichen plan et particulièrement de sa forme atrophique: lichen plan scléreux". Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris) (8): 790–791.

- ↑ Friedrich Jr., EG (1976). "Lichen sclerosus". J Reprod Med. 17 (3): 147–154. PMID 135083.

External links

- Lichen sclerosus Atlas

- NIAMS – Questions and Answers About Lichen Sclerosus

- NIAMS – Fast Facts About Lichen Sclerosus

- dermnetnz.org

- mayoclinic.com

- better medicine

- Medscape Reference Author: Jeffrey Meffert, MD; Chief Editor: Dirk M Elston, MD

Medical Pictures

- http://www.dermlectures.com/LecturesWMV.cfm?lectureID=88

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070927210529/http://dermis.multimedica.de/dermisroot/de/34088/diagnose.htm

- http://dermnetnz.org/immune/ls-imgs.html