Library stack

In library science and architecture, a stack or bookstack (often referred to as a library building's stacks) is a book storage area, as opposed to a reading area. More specifically, this term refers to a narrow-aisled, multilevel system of iron or steel shelving that evolved in the nineteenth century to meet increasing demands for storage space.[3] An "open-stack" library allows its patrons to enter the stacks to browse for themselves; "closed stacks" means library staff retrieve books for patrons on request.

Early development

French architect Henri Labrouste, shortly after making pioneering use of iron in the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve of 1850, created a four story iron stack for the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[4] In 1857, multilevel stacks with grated iron floors were installed in the British Library.[3] In 1876, William R. Ware designed a stack for Gore Hall at Harvard University.[1] In contrast to the structural relationship found in most buildings, the floors of these bookstacks did not support the shelving, but rather the reverse, the floors being attached to, and supported by, the shelving framework. Even the load of the building's roof, and of any non-shelving spaces above the stacks (such as offices), may be transmitted to the building's foundation through the shelving system itself. The building's external walls act as an envelope but provide no significant structural support.[4]

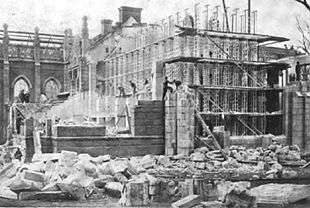

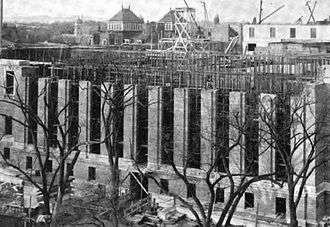

Library of Congress and the Snead system

For the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, completed in 1897, Bernard Richardson Green made a number of alterations to the Gore Hall design, including the use of all metal shelving. The contract was won by the Snead and Company Ironworks, which went on to install its standardized design in libraries around the country.[1] Notable examples include the Widener Library at Harvard and the seven level stack supporting the Rose Reading Room of the New York Public Library.[3]

Stacks were typically envisioned for access by library staff fetching books for patrons waiting elsewhere, and so were often built in ways making them unsuitable for public access. Increasing concern with opening stacks to the public,[4] the desire to construct buildings adaptable to changing uses,[3] and concerns over the feasibility of storing truly comprehensive collections of books contributed to the decline of the Snead stack. Angus Snead Macdonald, president of the Snead Company from 1915 to 1952, himself advocated for the transition to modular, open plan libraries in the mid twentieth century.[4]

Forms

For closed stacks, mobile shelving may be used to minimize floor space. With computerized indexing, filing by book size saves up to 40% space as well.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Snead Company (1915). Library Planning Bookstacks and Shelving. Architecture Press. pp. 11–12, 152–158.

- ↑ Lane, William Coolidge (May 1915). "The Widener Memorial Library of Harvard College". The Library Journal. 40 (5): 325.

- 1 2 3 4 Petroski, Henry (1999). The Book on the Book Shelf. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 167–168, 170–172, 184, 191.

- 1 2 3 4 Wiegand, Wayne, ed. (1994). Encyclopedia of Library History. Garland. pp. 352–355.

- ↑ Quito, Anne (13 October 2016). "The New York Public Library has adopted a very unusual sorting system". Quartz (publication). Atlantic Media. Retrieved 13 October 2016.