Li Ching-Yuen

| Li Ching-Yuen 李清雲 | |

|---|---|

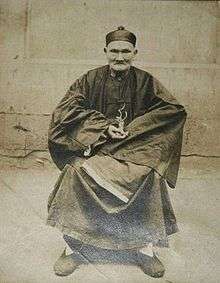

Li Ching-Yuen at the residence of National Revolutionary Army General Yang Sen in Wanxian, Sichuan in 1927 | |

| Born |

1677 or 1736 (claimed) Sichuan, Qing Dynasty |

| Died |

6 May 1933 (aged 197 or 256 ) Sichuan, Republic of China |

| Known for | Extreme longevity claim and spiritual practices by means of herbs |

| Height | 7 ft (223 to 237 cm)[1] |

| Spouse(s) | 24[2][3] |

Li Ching-Yuen or Li Ching-Yun (simplified Chinese: 李清云; traditional Chinese: 李清雲; pinyin: Lǐ Qīngyún) (claimed to be born 1677 or 1736 - died 6 May 1933) was a Chinese herbalist, martial artist and tactical advisor, known for his supposed extreme longevity.[4][5] He claimed to be born in 1736, while disputed records suggest 1677. Both claimed lifespans, of 197 and 256 years, far exceed the longest confirmed lifespan of 122 years and 164 days of French woman Jeanne Calment. His true date of birth was never determined and his claims have been dismissed by gerontologists as a myth.[6]

Biography

Li Ching-Yuen was born at an uncertain date (see Longevity below) in Qijiang Xian, Sichuan, Qing Empire.[7]

He spent most of his life in the mountains and was skilled in Qigong.[7] He worked as an herbalist, selling lingzhi, goji berry, wild ginseng, he shou wu and gotu kola along with other Chinese herbs, and lived off a diet of these herbs and rice wine.[8]

It was generally accepted in Sichuan, that Li was fully literate as a child, and that by his tenth birthday had travelled to Gansu, Shanxi, Tibet, Vietnam, Thailand and Manchuria with the purpose of gathering herbs, continuing with this occupation for a century, before beginning to purvey instead herbs gathered by others.[9]

It was after this he relocated to Kai Xian and there Li supposedly, at 72 years of age, in 1749, joined the army of provincial Commander-in-Chief Yeuh Jong Chyi, as a teacher of martial arts and as a tactical advisor.[7]

In 1927, the National Revolutionary Army General Yang Sen (揚森) invited him to his residence in Wan Xian, Sichuan, where the picture shown in this article was taken.[7]

The Chinese Warlord Wu Peifu (吳佩孚) took him into his home in an attempt to discover the secret of living 250 years.[9]

He died from natural causes on 6 May 1933 in Kai Xian, Sichuan, Republic of China and was survived by his 24th wife, a woman of 60 years.[3][9] Li supposedly produced over 200 descendants during his life span, surviving 23 wives.[2][3] Other sources credit him with 180 descendants, over 11 generations, living at the time of his death and 14 marriages.[7][9]

After his death, the aforementioned Yang Sen wrote a report about him, A Factual Account of the 250 Year-Old Good-Luck Man (一个250岁长寿老人的真实记载), in which he described Li's appearance: "He has good eyesight and a brisk stride; Li stands seven feet tall, has very long fingernails, and a ruddy complexion."[1][7]

Timeline of Li Ching-Yuen’s Life According to General Yang Sen[10]

In Qijiang County, Sichuan province, in the year 1677 Li Qingyun was born. By age thirteen he had embarked upon a life of gathering herbs in the mountains with three elders. At age fifty-one, he served as a tactical and topography advisor in the army of General Yu Zhongqi.[10]

When seventy-eight he retired from his military career after fighting in a battle at Golden River, and returned to a life of gathering herbs on Snow Mountain in Sichuan province. Due to his military service in the army of General Yu Zhongqi, the imperial government sent a document congratulating Li on his one hundredth year of life, as was subsequently done on his 150th and 200th birthdays.[10]

In 1928, Dean Wu Chung-chien of the Department of Education at Minkuo University (a university which seems to exist only in this story) discovered the imperial documents showing these birthday wishes to Li Qingyun. His discovery was first reported in the two leading Chinese newspapers of that period, North China Daily News and Shanghai Declaration News, and then maybe one year later, potentially in 1929 by The New York Times and Time magazine. Both of these theoretical Western publications also might have reported the death of Li Qingyun in May 1933.[10]

In 1908 Li Qingyun and his disciple Yang Hexuan published a book, The Secrets of Li Qingyun’s Immortality.[10]

In 1920, General Xiong Yanghe interviewed Li (both men were from the village of Chenjiachang of Wan County in Sichuan province), publishing an article about it in the Nanjing University paper that same year.[10]

In 1926, Wu Peifu (the famous Chinese warlord who dominated Beijing from 1917 to 1924) invited Li to Beijing. This visit coincides with Li teaching at the Beijing University Meditation Society at the invitation of the famous meditation master and author Yin Shi Zi.[10]

Then in 1927, General Yang Sen invited Li to Wanxian, where the first known photographs of Li were taken. Word spread throughout China of Li Qingyun, and Yang Sen's commander, General Chiang Kaishek, requested Li to visit Nanjing. However, when Yang Sen's envoys arrived at Li’s hometown of Chenjiachang, they were told by Li’s wife and disciples that he had died in nature, offering no more information. So, his actual date of death and location has never been verified.[10]

Longevity

Whereas Li Ching-Yuen himself claimed to have been born in 1736, Wu Chung-chieh, a professor of the Chengdu University (which was founded in 1978, 48 years AFTER the New York Times article), asserted that Li was born in 1677; according to a 1930 New York Times article, Wu discovered Imperial Chinese government records from 1827 congratulating Li on his 150th birthday, and further documents later congratulating him on his 200th birthday in 1877.[11] In 1928, a New York Times correspondent wrote that many of the old men in Li's neighborhood asserted that their grandfathers knew him when they were boys, and that he at that time was a grown man.[12]

However, a correspondent of The New York Times reported that "many who have seen him recently declare that his facial appearance is no different from that of persons two centuries his junior."[9] Moreover, gerontological researchers have viewed the age claim with extreme skepticism; the frequency of invalid age claims increases with the claimed age, rising from 65% of claims to ages 110-111 being invalid, to 98% of claims to being 115, with an 100% rate for claims of 120+ years. It is unclear though what, if any, implications these statistics have for the subject under discussion, as these figures refer to "false claims due to administrative errors" in Belgian public records.[6] Researchers have called his claim "fantastical" and also noted that his claimed age at death, 256 years, is a multiple of 8, which is considered good luck in China, and therefore is indicative of fabrication.[6] Additionally, the connection of Li's claimed age to his spiritual practices has been pointed to as another reason for doubt; researchers perceived that "these types of myths [that certain philosophies or religious practices allow a person to live to extreme old age] are most common in the Far East".[6]

One of Li's disciples, the Taijiquan Master Da Liu, told of his master's story: when 130 years old Master Li encountered in the mountains an older hermit, over 500 years old, who taught him Baguazhang and a set of Qigong with breathing instructions, movements training coordinated with specific sounds, and dietary recommendations. Da Liu reports that his master said that his longevity "is due to the fact that he performed the exercises every day – regularly, correctly, and with sincerity – for 120 years."[13]

The article "Tortoise-Pigeon-Dog", from the 15 May 1933 issue of Time reports on his history, and includes Li's answer to the secret of a long life:[11]

- Keep a quiet heart

- Sit like a tortoise

- Walk sprightly like a pigeon

- Sleep like a dog

An article in the Evening Independent claims that Li's supposed longevity is due to his experimentation with medicinal herbs in his capacity as a druggist, his discovery in the Yunnan mountains of herbs which "prevent the ravages of old age" and which he continued to use throughout his life.[3]

See also

- Longevity myths

- Longevity claims

- Oldest people

- Jeanne Calment, the oldest verified person

- Jiroemon Kimura, the oldest verified man

References

- 1 2 Yang, Sen. A Factual Account of the 250 Year-Old Good-Luck Man. Taipei, TW: Chinese and Foreign Literature Storehouse.

- 1 2 Harris, Timothy (2009). Living to 100 and Beyond. ACTEX Publications. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-56698-699-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Miami Herald (12 October 1929). "Living forever". The Evening Independent.

- ↑ "史上第一長壽!256歲的李青雲 長壽秘訣只有一個字". Likenews.tw. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "256歲娶24妻 李慶遠長壽秘訣公開 | 即時新聞 | 20130927 | 蘋果日報". Appledaily.com.tw. 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Young Robert D.; Desjardins Bertrand; McLaughlin Kirsten; Poulain Michel; Perls Thomas T. (2010). "Typologies of Extreme Longevity Myths". Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2010: 1–12. PMC 3062986

. PMID 21461047. doi:10.1155/2010/423087.

. PMID 21461047. doi:10.1155/2010/423087. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yang, Jwing-Ming (1989). Muscle/Tendon Changing and Marrow/Brain Washing Chi Kung: The Secret of Youth (PDF). YMAA Publication Centre. ISBN 0-940871-06-8.

- ↑ Castleman, Michael; Saul Hendler, Sheldon (1991). The healing herbs: the ultimate guide to the curative power of nature's medicines. Rodale Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-87857-934-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Li Ching-Yun Dead". The New York Times. 6 May 1933.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sen, Yang; Olson, Stuart Alve (2014). The Immortal: True Accounts of the 250-Year-Old Man, Li Qingyun. Valley Spirit Arts. p. xvi-xix. ISBN 978-1-889633-34-3.

- 1 2 "Tortoise-Pigeon-Dog". Time. 15 May 2012.

- ↑ Ettington, Martin K. (2008). Immortality: A History and How to Guide: Or How to Live to 150 Years and Beyond. Martin Ettington. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4404-6493-5.

- ↑ Liu, Da (1983). Taoist Health Exercise Book. Putnam.

External links

- Chi Kung – Qigong – Meditation

- CEMETRAC - Centro de Estudos da Medicina Tradicional e Cultura Chinesa (in Portuguese)

- Tortoise-Pigeon-Dog - Time article on Li Ching-Yuen (15 May 1933)