Letter of credit

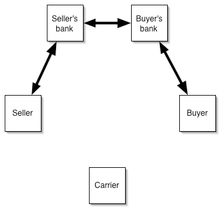

In modern business practice, a letter of credit (LC) also known as a Documentary Credit, is a written commitment by a bank issued after a request by an importer (foreign buyer) that payment will be made to the beneficiary (exporter) provided that the terms and conditions stated in the LC been met, as evidenced by the presentation of specified documents.[1]

A letter of credit is a method of payment that is an important part of international trade. They are particularly useful where the buyer and seller may not know each other personally and are separated by distance, differing laws in each country and different trading customs. It is generally considered that Letters of Credit offer a good balance of security between the buyer and the seller, because both the buyer and seller rely upon the security of banks and the banking system to ensure that payment is received and goods are provided. In a Letter of Credit transaction the goods are consigned to the order of the issuing bank, meaning that the bank will not release control of the goods until the buyer has either paid or undertaken to pay the bank for the documents.

In the event that the buyer is unable to make payment on the purchase, the seller may make a demand for payment on the bank. The bank will examine the beneficiary's demand and if it complies with the terms of the letter of credit, will honor the demand.[2] Most letters of credit are governed by rules promulgated by the International Chamber of Commerce known as Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits. The current version, UCP600, became effective July 1, 2007. Banks will typically require collateral from the purchaser for issuing a letter of credit and will charge a fee which is often a percentage of the amount covered by the letter of credit.

Origin

The name "letter of credit" derives from the French word "accréditation", a power to do something, which derives from the Latin "accreditivus", meaning trust.

Related terms

UCP 600 defines a number of terms related to letters of credit. These include:

- The Advising Bank is the bank that will inform the Beneficiary or their Nominated Bank of the credit, send the original credit to the Beneficiary or their Nominated Bank, and provide the Beneficiary or their Nominated Bank with any amendments to the letter of credit.

- The Applicant is the person or company who has requested the letter of credit to be issued; this will normally be the buyer.

- The Beneficiary is the person or company who will be paid under the letter of credit; this will normally be the seller.

- A Complying Presentation is a set of documents that meet with the requirements of the letter of credit and all of the rules relating to letters of credit.

- Confirming Bank is a bank other than the issuing bank that adds its confirmation to credit upon the issuing bank's authorization or request thus providing more security to beneficiary.

- Confirmation is an undertaking from a bank other than the issuing bank to pay the Beneficiary for a Complying Presentation, allowing the Beneficiary to further reduce payment risk, although Confirmation is usually at an extra cost.

- The Issuing Bank is the bank that issues the credit, usually following a request from an Applicant.

- The Nominated Bank is a bank mentioned within the letter of credit at which the credit is available.

Typical Process

After a sales contract has been negotiated and letter of credit has been agreed upon as the method of payment, the Applicant will contact a bank to ask for a letter of credit to be issued, and once the issuing bank has ascertained that the Applicant will be able to pay for the goods, it will issue the letter of credit. Once the Beneficiary receives the letter of credit, it will check the terms to ensure that it matches with the contract and will either arrange for shipment of the goods or ask for an amendment to the letter of credit so that it meets with the terms of the contract. The letter of credit is limited in terms of time, the validity of credit, the last date of shipment, and in terms of how much late after shipment the documents may be presented to the Nominated Bank.

Once the goods have been shipped, the Beneficiary will present the set of requested documents to the Nominated Bank. This bank will check the documents, and if they comply with the terms of the Letter of Credit, the issuing Bank is bound to honor the terms of the letter of credit by paying the Beneficiary.

If the documents do not comply with the terms of the letter of credit they are considered Discrepant. At this point the Nominated Bank will inform the Beneficiary of the discrepancy and offer a number of options depending on the circumstances after consent of applicant. If the discrepancies are minor, it may be possible to present corrected documents to the bank to make the presentation compliant. Documents presented after the time limits mentioned in the credit are also considered discrepant.

If corrected documents cannot be supplied in time the documents may be forwarded directly to the issuing bank "in trust"; effectively in the hope that the Applicant will accept the documents. Documents forwarded in trust remove the payment security of a letter of credit so this route must only be used as a last resort.

Some banks will offer to "Telex for Approval" or similar. This is where the Nominated Bank holds the documents, but sends a message to the Issuing Bank asking if discrepancies are acceptable. This is more secure than sending documents in trust.

Documents that may be Requested for Presentation

To receive payment, an exporter or shipper must present the documents required by the LC. Typically the letter of credit will request an original Bill of lading as the use of a title document such as this is critical to the functioning of the Letter of Credit. However, the list and form of documents is open to negotiation and might contain requirements to present documents issued by a neutral third party evidencing the quality of the goods shipped, or their place of origin or place. Typical types of documents in such contracts might include:

- Financial documents — bill of exchange, co-accepted draft

- Commercial documents — invoice, packing list

- Shipping documents — bill of lading (ocean or multi-modal or charter party), airway bill, lorry/truck receipt, railway receipt, CMC other than mate receipt, forwarder cargo receipt

- Official documents — license, embassy legalization, origin certificate, inspection certificate, phytosanitary certificate

- Insurance documents — insurance policy or certificate, but not a cover note.

But the range of documents that may be requested by the applicant is vast, and varies considerably by country and commodity.

Legal principles governing documentary credits

One of the primary peculiarities of the documentary credit is that the payment obligation is independent from the underlying contract of sale or any other contract in the transaction. The bank’s obligation is defined by the terms of the LC alone, and the contract of sale is not considered. The defenses available to the buyer arising out of the sale contract do not concern the bank and in no way affect its liability.[3] Article 4(a) of the UCP600 states this principle clearly.

The fundamental principle of all letters of credit is that letters of credit deal with documents and not with goods, as stated by Article 5 of UCP600.

Accordingly, if the documents tendered by the beneficiary or their agent are in order, then in general the bank is obliged to pay without further qualifications. As a result the buyer bears the risk that a dishonest seller may present documents which comply with the letter of credit and receive payment, only to later discover that documents are fraudulent and the goods are not in accordance with the contract. To avoid this sort of risk to buyer, a variety of LCs are available with variations in terms of payment.

The policies behind adopting this principle of abstraction are purely commercial and reflect a party’s expectations.

Firstly, if the validity of documents was the banks' responsibility, they would be burdened with investigating the underlying facts of each transaction, and would be much less inclined to issue documentary credits because of the risk, inconvenience, and expense incurred.

Secondly, documents required under the LC, could in certain circumstances, be different from those required under the sale transaction. This would place banks in a dilemma in deciding which terms to follow if required to look behind the credit agreement.

Thirdly, since the basic function of the credit is to provide a seller with the certainty of payment for documentary duties, it would seem necessary that banks should honor their obligation in spite of any buyer allegations of misfeasance.[4] Courts have emphasized that buyers always have a remedy for an action upon the contract of sale and that it would be a calamity for the business world if a bank had to investigate every breach of contract.

The “principle of strict compliance” also aims to make the banks' duty of effecting payment against documents easy, efficient and quick. Under the previous rules for Letters of Credit (up to UCP 500) the documents tendered under the credit must not deviate from the language of the credit otherwise the bank is entitled to withhold payment, even if the deviation is purely terminological or even typographical.[5] The general legal maxim de minimis non curat lex (literally "The law does not concern itself with trifles") has no place in the field.

With the UCP 600 rules the ICC sought to make the rules more flexible, suggesting that data in a document "need not be identical to, but must not conflict with data in that document, any other stipulated document, or the credit", as a way to account for any minor documentary errors. However in practice many banks still hold to the principle of strict compliance, since it offers concrete guarantees to all parties.

Types

- Import/export — The same credit can be termed an import or export LC[6] depending on whose perspective is considered. For the importer it is termed an Import LC and for the exporter of goods, an Export LC.

- Revocable — The buyer and the issuing bank are able to manipulate the LC or make corrections without informing or getting permissions from the seller. According to UCP 600, all LCs are irrevocable, hence this type of LC is obsolete.

- Irrevocable — Any changes (amendment) or cancellation of the LC (except it is expired) is done by the applicant through the issuing bank. It must be authenticated and approved by the beneficiary.

- Confirmed — An LC is said to be confirmed when a second bank adds its confirmation (or guarantee) to honor a complying presentation at the request or authorization of the issuing bank.

- Unconfirmed — This type does not acquire the other bank's confirmation.

- Restricted — Only one advising bank can purchase a bill of exchange from the seller in the case of a restricted LC.

- Unrestricted — The confirmation bank is not specified, which means that the exporter can show the bill of exchange to any bank and receive a payment on an unrestricted LC.

- Transferrable — The exporter has the right to make the credit available to one or more subsequent beneficiaries. Credits are made transferable when the original beneficiary is a middleman and does not supply the merchandise, but procures goods from suppliers and arranges them to be sent to the buyer and does not want the buyer and supplier know each other.[7]

- The middleman is entitled to substitute his own invoice for the supplier's and acquire the difference as profit.

- A letter of credit can be transferred to the second beneficiary at the request of the first beneficiary only if it expressly states that the letter of credit is "transferable". A bank is not obligated to transfer a credit.

- A transferable letter of credit can be transferred to more than one alternate beneficiary as long as it allows partial shipments.

- The terms and conditions of the original credit must be replicated exactly in the transferred credit. However, to keep the workability of the transferable letter of credit, some figures can be reduced or curtailed.

- Amount

- Unit price of the merchandise (if stated)

- Expiry date

- Presentation period

- Latest shipment date or given period for shipment.

- The first beneficiary may demand from the transferring bank to substitute for the applicant. However, if a document other than the invoice must be issued in a way to show the applicant's name, in such a case that requirement must indicate that in the transferred credit it will be free.

- Transferred credit cannot be transferred again to a third beneficiary at the request of the second beneficiary.

- Untransferable — A credit that the seller cannot assign all or part of to another party. In international commerce, all credits are untransferable.

- Deferred / Usance — A credit that is not paid/assigned immediately after presentation, but after an indicated period that is accepted by both buyer and seller. Typically, seller allows buyer to pay the required money after taking the related goods and selling them.

- At Sight — A credit that the announcer bank immediately pays after inspecting the carriage documents from the seller.

- Red Clause — Before sending the products, seller can take the pre-paid part of the money from the bank. The first part of the credit is to attract the attention of the accepting bank. The first time the credit is established by the assigner bank, is to gain the attention of the offered bank. The terms and conditions were typically written in red ink, thus the name.

- Back to Back — A pair of LCs in which one is to the benefit of a seller who is not able to provide the corresponding goods for unspecified reasons. In that event, a second credit is opened for another seller to provide the desired goods. Back-to-back is issued to facilitate intermediary trade. Intermediate companies such as trading houses are sometimes required to open LCs for a supplier and receive Export LCs from buyer.

- Standby Letter of Credit: - Operates like a Commercial Letter of Credit, except that typically it is retained as a "standby" instead of being the intended payment mechanism. UCP600 article 1 provides that the UCP applies to Standbys; ISP98 applies specifically to Standby letters of Credit; and the United Nations Convention on Independent Guarantees and Standby letters of Credit applies to a small number of countries that have ratified the Convention.

Pricing

Issuance charges, covering negotiation, reimbursements and other charges are paid by the applicant or as per the terms and conditions of the LC. If the LC does not specify charges, they are paid by the Applicant. Charge-related terms are indicated in field 71B.

Legal basis

Legal writers have failed to satisfactorily reconcile the bank’s undertaking with any contractual analysis. The theories include: the implied promise, assignment theory, the novation theory, reliance theory, agency theories, estoppels and trust theories, anticipatory theory and the guarantee theory.[8]

Although documentary credits are enforceable once communicated to the beneficiary, it is difficult to show any consideration given by the beneficiary to the banker prior to the tender of documents. In such transactions the undertaking by the beneficiary to deliver the goods to the applicant is not sufficient consideration for the bank’s promise because the contract of sale is made before the issuance of the credit, thus consideration in these circumstances is past. However, the performance of an existing duty under a contract may be a valid consideration for a new promise made by the bank, provided that there is some practical benefit to the bank[9] A promise to perform owed to a third party may also constitute a valid consideration.[10]

Another theory asserts that it is feasible to typify letter of credit as a collateral contract for a third-party beneficiary because three different entities participate in the transaction: the seller, the buyer, and the banker. Because letters of credit are prompted by the buyer’s necessity and in application of the theory of Jean Domat the cause of a LC is to release the buyer of his obligation to pay directly to the seller. Therefore, a LC theoretically fits as a collateral contract accepted by conduct or in other words, an implied-in-fact contract under the framework for third party beneficiary where the buyer participates as the third party beneficiary with the bank acting as the stipulator and the seller as the promisor. The term "beneficiary" is not used properly in the scheme of an LC because a beneficiary (also, in trust law, cestui que use) in the broadest sense is a natural person or other legal entity who receives money or other benefits from a benefactor. Note that under the scheme of letters of credit, banks are neither benefactors of sellers nor benefactors of buyers and the seller receives no money in gratuity mode. Thus is possible that a “letter of credit” was one of those contracts that needed to be masked to disguise the “consideration or privity requirement”. As a result, this kind of arrangement, would make letter of credit to be enforceable under the action assumpsit because of its promissory connotation.[11]

A few countries have created statutes in relation to letters of credit. For example, most jurisdictions in the United States (U.S.) have adopted Article 5 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). These statutes are designed to work with the rules of practice including UCP and ISP98. These rules of practice are incorporated into the transaction by agreement of the parties. The latest version of the UCP is the UCP600 effective July 1, 2007. Since the UCP are not laws, parties have to include them into their arrangements as normal contractual provisions.

International Trade Payment methods

- Documentary Credit (more secure for seller as well as buyer) — Subject to ICC's UCP 600, the bank gives an undertaking (on behalf of buyer and at the request of applicant) to pay the beneficiary the value of the goods shipped if acceptable documents are submitted and if the stipulated terms and conditions are strictly complied with. The buyer can be confident that the goods he is expecting only will be received since it will be evidenced in the form of certain documents called for meeting the specified terms and conditions while the supplier can be confident that if he meets the stipulations his payment for the shipment is guaranteed by bank, who is independent of the parties to the contract.

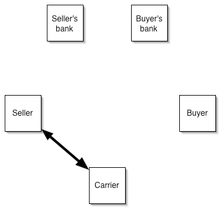

- Documentary collection (more secure for buyer and to a certain extent to seller) — Also called "Cash Against Documents". Subject to ICC's URC 525, sight and usance, for delivery of shipping documents against payment or acceptances of draft, where shipment happens first, then the title documents are sent to the buyer's bank by seller's bank, for delivering documents against collection of payment/acceptance

- Direct payment (most secure for buyer) — The supplier ships the goods and waits for the buyer to remit the bill, on open account terms.

Risk situations

Letters of Credit are often used in international transactions to ensure that payment will be received where the buyer and seller may not know each other and are operating in different countries. In this case the seller is exposed to a number of risks such as credit risk, and legal risk caused by the distance, differing laws and difficulty in knowing each party personally. some of the other risks inherent in international trade include:

- Fraud Risks

- The payment will be obtained for nonexistent or worthless merchandise against presentation by the beneficiary of forged or falsified documents.

- Credit itself may be funded.

- Sovereign and Regulatory Risks

- Performance of the Documentary Credit may be prevented by government action outside the control of the parties.

- Legal Risks

- Possibility that performance of a documentary credit may be disturbed by legal action relating directly to the parties and their rights and obligations under the documentary credit.

- Force Majeure and Frustration of Contract

- Performance of a contract – including an obligation under a documentary credit relationship – is prevented by external factors such as natural disasters or armed conflicts.

- Applicant

- Non-delivery of Goods

- Short shipment

- Inferior quality

- Early / late shipment

- Damaged in transit

- Foreign exchange

- Failure of bank viz issuing bank / collecting bank

- Issuing Bank

- Insolvency of the applicant

- Fraud risk, sovereign and regulatory risk and legal risks

- Reimbursing Bank

- no obligation to reimburse the claiming bank unless it has issued a reimbursement undertaking.

- Beneficiary

- Failure to comply with credit conditions

- Failure of, or delays in payment from, the issuing bank

See also

- Bank payment obligation

- Buyer's credit

- Documentary collection

- Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits

References

- ↑ https://www.export.gov/article?id=Chapter-3-Letters-of-Credit

- ↑ Sinclair, James. "Letter of Credit and UCP600, definition". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ Ficom S.A. v. Socialized Cadex [1980] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 118.

- ↑ United City Merchants (Investments) Ltd v Royal Bank of Canada (The American Accord) [1983] 1.A.C.168 at 183

- ↑ J. H. Rayner & Co., Ltd., and the Oil seeds Trading Company, Ltd. v.Ham bros Bank Limited [1942] 73 Ll. L. Rep. 32

- ↑ http://www.bwtradefinance.com/letter-of-credit-lc

- ↑ Sinclair, James. "What are the different types of Letter of Credit?". Trade Finance Global. Trade Finance Global. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ Finkelstein, Herman Norman (1930). Legal Aspects of Commercial Letters of Credit.

- ↑ William v Roffey Brothers & Nicholls (contractors) Ltd

- ↑ Scotson v Pegg

- ↑ Menendez, Andres. "Letter of Credit, its Relation with Stipulation for the Benefit of a Third Party". SSRN 2019474

.

.

External links

- Text of UCP 600, document, hosted at Faculty of Law, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal

- Letter of Credit Information, Procedure and Videos.

- Letter of Credit in China.

- Anatomy of a Letter of Credit, showing an actual negotiated letter of credit

- Letters of Credit and How They Work

- http://banki.ir/danestaniha/214-general/2468-lc (in Persian)

- Letter of Credit, its Relation with Stipulation for the Benefit of a Third Party

- AplonTrade: A free sample tool for exporting Letters of Credit by using SWIFT messages

- A sample Letter of Credit

- A Guide to Letters of Credit, different types and how they work