Les préludes

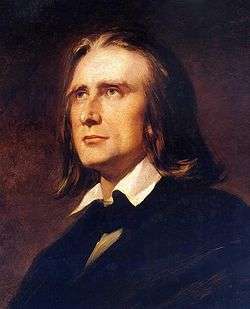

Les préludes is the third of Franz Liszt's thirteen symphonic poems. It is listed as S.97 in Humphrey Searle's catalogue of Liszt's music. The music is partly based on Liszt's 1844/5 choral cycle Les quatre élémens (The Four Elements). Its premiere was in 1854, directed by Liszt himself. The score was published in 1856 by Breitkopf & Härtel, who also published the musical parts in 1865.[1] Les préludes is the earliest example of an orchestral work entitled "symphonic poem".

Form

Much of the music of Les préludes derives from Liszt's earlier choral cycle Les quatre élémens (The Four Elements). (1844/5). These settings were later orchestrated, and an orchestral overture was written for them.

Les préludes is written for a large orchestra of strings, woodwind, brass (including tuba and bass trombone), harp and a variety of percussion instruments (timpani, side drum, bass drum and cymbals). It comprises the following sections:[2]

- Question (Introduction and Andante maestoso) (bars 1–46)

- Love (bars 47–108)

- Storm (bars 109–181)

- Bucolic calm (bars 182–344)

- Battle and victory (bars 345–420) (including recapitulation of 'Question', bar 405 ff.)

In bar 3 one of the main motifs of Les préludes (the notes C-B-E) is introduced. During the introduction this motif is frequently repeated in different forms. It is, however, the head of a melody, which in its entire form is for the first time played in bars 47ff. The melody was taken from the chorus piece Les astres (The Stars) in Les quatres élémens, where it is sung to the words, "Hommes épars sur le globe qui roule" ("Solitary men on the rolling globe").[3]

Richard Taruskin points out that the sections of Les préludes "[correspond] to the movements of a conventional symphony if not in the most conventional order".[4] He adds that "[t]he music, whilst heavily indebted in concept to Berlioz, self-consciously advertises its descent from Beethoven even as it flaunts its freedom from the formal constraints to which Beethoven had submitted [...] The standard "there and back" construction that had controlled musical discourse since at least the time of the old dance suite continues to impress its general shape on the sequence of programatically derived events."[5]

The programme

The full title of the piece, "Les préludes (d'après Lamartine)" refers to an Ode from Alphonse de Lamartine's Nouvelles méditations poétiques of 1823.

However, the piece was originally conceived as the overture to Les quatre élémens, settings of poems by Joseph Autran, which itself was drawn from music of the four choruses of the cycle. It seems that Liszt took steps to obscure the origin of the piece, and that this included the destruction of the original overture's title page, and the re-ascription of the piece to Lamartine's poem, which however, does not itself contain anything like the music's 'question'.[6]

The 1856 published score includes a text preface, which however is not from Lamartine.

- What else is our life but a series of preludes to that unknown Hymn, the first and solemn note of which is intoned by Death?—Love is the glowing dawn of all existence; but what is the fate where the first delights of happiness are not interrupted by some storm, the mortal blast of which dissipates its fine illusions, the fatal lightning of which consumes its altar; and where is the cruelly wounded soul which, on issuing from one of these tempests, does not endeavour to rest his recollection in the calm serenity of life in the fields? Nevertheless man hardly gives himself up for long to the enjoyment of the beneficent stillness which at first he has shared in Nature's bosom, and when "the trumpet sounds the alarm", he hastens, to the dangerous post, whatever the war may be, which calls him to its ranks, in order at last to recover in the combat full consciousness of himself and entire possession of his energy.[7]

The earliest version of this preface was written in March 1854 by Liszt's companion Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein.[8] This version comprises voluminous reflections of the Princess, into which some lines of quotations from the ode by Lamartine are incorporated.[9] It was drastically shortened for publication in April 1856 as part of the score; there only the sentence, "the trumpet sounds the alarm" and the title "Les préludes", survive from Lamartine's poem.

A different version of the preface was written for the occasion of a performance of Les préludes on December 6, 1855, in Berlin. In the 1855 version the connection with Lamartine is reduced to his alleged query, "What else is our life but a series of preludes to that unknown Hymn, the first and solemn note of which is intoned by Death?"[10] However this sentence was actually written not by Lamartine, but by Princess Wittgenstein.

For the occasion of a performance of Les préludes on April 30, 1860, in Prague a further version of the preface was made. This version was probably written by Hans von Bülow who directed the performance.[11] It is rather short and contains no reference to Lamartine at all. According to this version, Les préludes illustrates the development of a man from his early youth to maturity.[12] In this interpretation, Les préludes may be taken as part of a sketched musical autobiography.

Liszt himself, in a letter to Eduard Liszt of March 26, 1857, gave another hint with regard to the title Les préludes. According to this, Les préludes represents the prelude to Liszt's own path of composition.[13]

The first symphonic poem

With the first performance of the work a new genre was introduced. Les préludes is the earliest example for an orchestral work that was performed as "symphonic poem". In a letter to Franz Brendel of February 20, 1854, Liszt simply called it "a new orchestral work of mine (Les préludes)".[14] Two days later, in the announcement in the Weimarische Zeitung of February 22, 1854, of the concert on February 23, it was called "Les preludes— symphonische Dichtung". The term "symphonic poem" was thus invented.

Critical reception

The critic Eduard Hanslick, who believed in 'absolute music', lambasted Les préludes. In an 1857 article, following a performance in Vienna, he denounced the idea of a 'symphonic poem' as a contradiction in terms. He also denied that music was in any way a 'language' that could express anything, and mocked Liszt's assertion that it could translate concrete ideas or assertions. The aggrieved Liszt wrote to his cousin Eduard "The doctrinaire Hanslick could not be favourable to me; his article is perfidious".[15] Other critics, such as Felix Draeseke, were more supportive.[16]

Early performances in America were not appreciated by conservative critics there. At an 1857 performance of the piano duet arrangement, the critic of Dwight's Journal of Music wrote:

What shall we say of The Preludes, a Poesie Symphonique by Liszt [...] The poetry we listened for in vain. It was lost as it were in the smoke and stunning tumult of a battlefield. There were here and there brief, fleeting fragments of something delicate and sweet to ear and mind, but these were quickly swallowed up in one long, monotonous, fatiguing melée of convulsive, crashing, startling masses of tone, flung back and forth as if in rivalry from instrument to instrument. We must have been very stupid listeners; but we felt after it as if we had been stoned, and beaten, and trampled under foot, and in all ways evilly entreated.[17]

Nevertheless, the work is more recently rated by Leslie Howard as "easily the most popular of Liszt’s thirteen symphonic poems."[18]

Arrangements

In the beginning of 1859 Les préludes was successfully performed in New York City.[19] Karl Klauser, New York, made a piano arrangement, which in 1863 was submitted to Liszt. In a letter to Franz Brendel of September 7, 1863, Liszt wrote that Les préludes in Klauser's arrangement was a hackneyed piece, but he had played it through again, to touch up the closing movement of Klauser's arrangement and give it new figuration.[20] Liszt sent Klauser's revised arrangement to the music publisher Julius Schuberth of Leipzig,[21] who was able to publish it in America. In Germany, due to the legal situation of that time, Breitkopf & Härtel as original publishers of Les préludes owned all rights on all kinds of arrangements. For this reason, in 1865 or 1866 Klauser's arrangement was published not by Schuberth but by Breitkopf & Härtel.

Besides Klauser's arrangement there were further piano arrangements by August Stradal and Carl Tausig. Liszt made his own arrangements for two pianos and for piano duet. There were also arrangements for harmonium and piano by A. Reinhard and for military orchestra by L. Helfer.[22] In recent times Matthew Cameron has prepared his own piano arrangement of Les préludes.

Year's end tradition at Interlochen

A performance of Les préludes concludes each summer camp session at the Interlochen Center for the Arts. The piece is conducted by the president of the institution and performed by the camp's large ensembles.[23]

References

- Notes

- ↑ Müller-Reuter (1909) p. 266.

- ↑ Taruskin (2010), p. 423

- ↑ Haraszti (1953), p. 121.

- ↑ Taruskin (2010), p. 423

- ↑ Taruskin (2010), pp. 424, 427

- ↑ Taruskin (2010), p. 425

- ↑ This English version is taken from vol. I, 2 of the complete edition of Liszt's musical works of the "Franz Liszt Stiftung".

- ↑ Walker (1989) p. 307, n. 13.

- ↑ Walker (1989) p. 297

- ↑ Müller-Reuter (1909), p. 300.

- ↑ Haraszti (1953), p. 128f.

- ↑ Müller-Reuter(1909), p. 301.

- ↑ La Mara (ed.): Liszts Briefe, Band 1, translated to English by Constance Bache, No. 180.

- ↑ ibid, No. 108.

- ↑ Walker (1989), p.363

- ↑ Gibbs (2010), pp. 485-7.

- ↑ Cited in Modolell (2014), p.13

- ↑ Howard (1996).

- ↑ See Liszt's letter to Julius Schuberth of March 9, 1859, in Jung (ed.): Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, p. 165.

- ↑ La Mara (ed.): Liszts Briefe, Band 2, translated to English by Constance Bache, No. 20.

- ↑ Liszt's letter to Brendel of September 7, 1863, as cited above.

- ↑ Raabe: Liszts Schaffen, p. 299.

- ↑ http://camp.interlochen.org/media/video-les-preludes-2014. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Sources

- Haraszti, Emile: Génèse des préludes de Liszt qui n'ont aucun rapport avec Lamartine, in Révue de musicologie 35 (1953), p. 111ff.

- Howard, Leslie (1996). Les préludes – Poème symphonique, liner notes for Hyperion Records CDA67015, accessed 2 January 2015.

- Modollel, Jorge L. (2014). The Critical Reception of Liszt's Symphonic and Choral Works in the United States, 1857-1890, Master's Thesis, University of Miami, accessed 2 January 2015.

- Müller-Reuter, Theodor: Lexikon der deutschen Konzertliteratur, 1. Band, Leipzig 1909.

- Raabe, Peter: Liszts Schaffen, Cotta, Stuttgart, Berlin 1931.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195384833.

- Walker, Alan: Franz Liszt, The Virtuoso Years, revised edition, Cornell University Press 1987.

- Walker, Alan: Franz Liszt, The Weimar Years (1848–1861), Cornell University Press 1989.

External links

- Les préludes (Orchestral version), (Solo piano version), (Two piano version), (Piano duet version): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)