Anatomy of the human nose

| Human nose | |

|---|---|

Human nose in profile | |

Internal anatomy of the nose | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Sphenopalatine artery and greater palatine artery |

| Vein | Facial vein |

| Nerve | External nasal nerve |

| Latin | Nasus |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | n_10/12578550 |

The visible part of the human nose is the protruding part of the face that bears the nostrils. The shape of the nose is determined by the ethmoid bone and the nasal septum, which consists mostly of cartilage and which separates the nostrils. On average the nose of a male is larger than that of a female.[1]

The nasal root is the top of the nose, forming an indentation at the suture where the nasal bones meet the frontal bone. The anterior nasal spine is the thin projection of bone at the midline on the lower nasal margin, holding the cartilaginous center of the nose.[2] Adult humans have nasal hairs in the anterior nasal passage.

Structure

Bone anatomy

In the upper portion of the nose, the paired nasal bones attach to the frontal bone. Above and to the side (superolaterally), the paired nasal bones connect to the lacrimal bones, and below and to the side (inferolaterally), they attach to the ascending processes of the maxilla (upper jaw). Above and to the back (posterosuperiorly), the bony nasal septum is composed of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. The vomer bone lies below and to the back (posteroinferiorly), and partially forms the choanal opening into the nasopharynx, (the upper portion of the pharynx that is continuous with the nasal passages). The floor of the nose comprises the premaxilla bone and the palatine bone, the roof of the mouth.

The nasal septum is composed of the quadrangular cartilage, the vomer bone (the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone), aspects of the premaxilla, and the palatine bones. Each lateral nasal wall contains three pairs of turbinates (nasal conchae), which are small, thin, shell-form bones: (i) the superior concha, (ii) the middle concha, and (iii) the inferior concha, which are the bony framework of the turbinates. Lateral to the turbinates is the medial wall of the maxillary sinus. Inferior to the nasal conchae (turbinates) is the meatus space, with names that correspond to the turbinates, e.g. superior turbinate, superior meatus, et alii. The internal roof of the nose is composed by the horizontal, perforated cribriform plate (of the ethmoid bone) through which pass sensory filaments of the olfactory nerve (Cranial nerve I); finally, below and behind (posteroinferior) the cribriform plate, sloping down at an angle, is the bony face of the sphenoid sinus.

- Cartilaginous pyramid of the nose

The cartilaginous septum (septum nasi) extends from the nasal bones in the midline (above) to the bony septum in the midline (posteriorly), then down along the bony floor. The septum is quadrangular; the upper half is flanked by two (2) triangular-to-trapezoidal cartilages: the upper lateral-cartilages, which are fused to the dorsal septum in the midline, and laterally attached, with loose ligaments, to the bony margin of the pyriform (pear-shaped) aperture, while the inferior ends of the upper lateral-cartilages are free (unattached). The internal area (angle), formed by the septum and upper lateral-cartilage, constitutes the internal valve of the nose; the sesamoid cartilages are adjacent to the upper lateral-cartilages in the fibroareolar connective tissue. The respective external valve of each nose is variably dependent upon the size, shape, and strength of the lower lateral cartilage.[3]

Beneath the upper lateral-cartilages lay the lower lateral-cartilages; the paired lower lateral-cartilages swing outwards, from medial attachments, to the caudal septum in the midline (the medial crura) to an intermediate crus (shank) area. Finally, the lower lateral-cartilages flare outwards, above and to the side (superolaterally), as the lateral crura; these cartilages are mobile, unlike the upper lateral cartilages. Furthermore, some persons present anatomical evidence of nasal scrolling—i.e. an outward curving of the lower borders of the upper lateral-cartilages, and an inward curving of the cephalic borders of the alar cartilages.

Soft tissue

- Nasal skin – Like the underlying bone-and-cartilage (osseo-cartilaginous) support framework of the nose, the external skin is divided into vertical thirds (anatomic sections); from the glabella (the space between the eyebrows), to the bridge, to the tip, for corrective plastic surgery, the nasal skin is anatomically considered, as the:

- Upper third section – the skin of the upper nose is thick, and relatively distensible (flexible and mobile), but then tapers, adhering tightly to the osseo-cartilaginous framework, and becomes the thinner skin of the dorsal section, the bridge of the nose.

- Middle third section – the skin overlying the bridge of the nose (mid-dorsal section) is the thinnest, least distensible, nasal skin, because it most adheres to the support framework.

- Lower third section – the skin of the lower nose is as thick as the skin of the upper nose, because it has more sebaceous glands, especially at the nasal tip.

- Nasal lining – At the vestibule, the human nose is lined with a mucous membrane of squamous epithelium, which tissue then transitions to become columnar respiratory epithelium, a pseudo-stratified, ciliated (lash-like) tissue with abundant seromucinous glands, which maintains the nasal moisture and protects the respiratory tract from bacteriologic infection and foreign objects.

- Nasal muscles – The movements of the human nose are controlled by groups of facial and neck muscles that are set deep to the skin; they are in four (4) functional groups that are interconnected by the nasal superficial aponeurosis—the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS)—which is a sheet of dense, fibrous, collagenous connective tissue that covers, invests, and forms the terminations of the muscles.

- the elevator muscle group includes the procerus muscle and the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle.

- the depressor muscle group includes the alar nasalis muscle and the depressor septi nasi muscle.

- the compressor muscle group includes the transverse nasalis muscle.

- the dilator muscle group includes the dilator naris muscle that expands the nostrils; it is in two parts: (i) the dilator nasi anterior muscle, and (ii) the dilator nasi posterior muscle.

Nasal subunits and nasal segments

To plan, map, and execute the surgical correction of a nasal defect or deformity, the structure of the external nose is divided into nine (9) aesthetic nasal subunits, and six (6) aesthetic nasal segments, which provide the plastic surgeon with the measures for determining the size, extent, and topographic locale of the nasal defect or deformity.

- The surgical nose as nine (9) aesthetic nasal subunits

- tip subunit

- columellar subunit

- right alar base subunit

- right alar wall subunit

- left alar wall subunit

- left alar base subunit

- dorsal subunit

- right dorsal wall subunit

- left dorsal wall subunit

In turn, the nine (9) aesthetic nasal subunits are configured as six (6) aesthetic nasal segments; each segment comprehends a nasal area greater than that comprehended by a nasal subunit.

- The surgical nose as six (6) aesthetic nasal segments

- the dorsal nasal segment

- the lateral nasal-wall segments

- the hemi-lobule segment

- the soft-tissue triangle segments

- the alar segments

- the columellar segment

Using the co-ordinates of the subunits and segments to determine the topographic location of the defect on the nose, the plastic surgeon plans, maps, and executes a rhinoplasty procedure. The unitary division of the nasal topography permits minimal, but precise, cutting, and maximal corrective-tissue coverage, to produce a functional nose of proportionate size, contour, and appearance for the patient. Hence, if more than 50 per cent of an aesthetic subunit is lost (damaged, defective, destroyed) the surgeon replaces the entire aesthetic segment, usually with a regional tissue graft, harvested from either the face or the head, or with a tissue graft harvested from elsewhere on the patient’s body.[4]

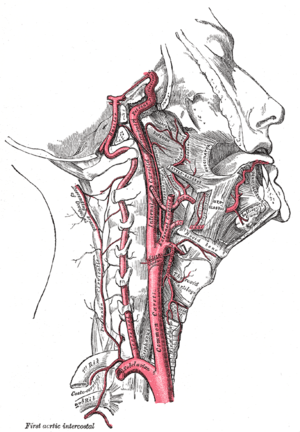

Blood supply and drainage

Like the face, the human nose is well vascularized with arteries and veins, and thus supplied with abundant blood. The principal arterial blood-vessel supply to the nose is two-fold: (i) branches from the internal carotid artery, the branch of the anterior ethmoid artery, the branch of the posterior ethmoid artery, which derive from the ophthalmic artery; (ii) branches from the external carotid artery, the sphenopalatine artery, the greater palatine artery, the superior labial artery, and the angular artery.

The external nose is supplied with blood by the facial artery, which becomes the angular artery that courses over the superomedial aspect of the nose. The sellar region (sella turcica, “Turkish chair”) and the dorsal region of the nose are supplied with blood by branches of the internal maxillary artery (infraorbital) and the ophthalmic arteries that derive from the internal common carotid artery system.

Internally, the lateral nasal wall is supplied with blood by the sphenopalatine artery (from behind and below) and by the anterior ethmoid artery and the posterior ethmoid artery (from above and behind). The nasal septum also is supplied with blood by the sphenopalatine artery, and by the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries, with the additional circulatory contributions of the superior labial artery and of the greater palatine artery. These three (3) vascular supplies to the internal nose converge in the Kiesselbach plexus (the Little area), which is a region in the anteroinferior-third of the nasal septum, (in front and below). Furthermore, the nasal vein vascularisation of the nose generally follows the arterial pattern of nasal vascularisation. The nasal veins are biologically significant, because they have no vessel-valves, and because of their direct, circulatory communication to the sinus caverns, which makes possible the potential intracranial spreading of a bacterial infection of the nose. Hence, because of such an abundant nasal blood supply, tobacco smoking does therapeutically compromise post-operative healing.

Lymphatic drainage

The pertinent nasal lymphatic system arises from the superficial mucosa, and drains posteriorly to the retropharyngeal nodes (in back), and anteriorly (in front), either to the upper deep cervical nodes (in the neck), or to the submandibular glands (in the lower jaw), or into both the nodes and the glands of the neck and the jaw.

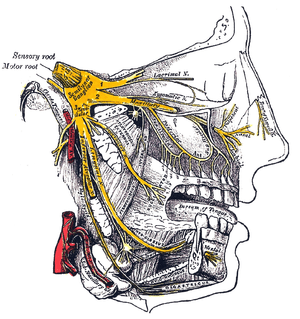

Innervation

The sensations registered by the human nose derive from the first two (2) branches of cranial nerve V, the trigeminal nerve (nervus trigeminis). The nerve listings indicate the respective innervation (sensory distribution) of the trigeminal nerve branches within the nose, the face, and the upper jaw (maxilla).

- The indicated nerve serves the named anatomic facial and nasal regions

- Ophthalmic division innervation

- Lacrimal nerve – conveys sensation to the skin areas of the lateral orbital (eye socket) region, except for the lacrimal gland.

- Frontal nerve – conveys sensation to the skin areas of the forehead and the scalp.

- Supraorbital nerve – conveys sensation to the skin areas of the eyelids, the forehead, and the scalp.

- Supratrochlear nerve – conveys sensation to the medial region of the eyelid skin area, and the medial region of the forehead skin.

- Nasociliary nerve – conveys sensation to the skin area of the nose, and the mucous membrane of the anterior (front) nasal cavity.

- Anterior ethmoid nerve – conveys sensation in the anterior (front) half of the nasal cavity: (a) the internal areas of the ethmoid sinus and the frontal sinus; and (b) the external areas, from the nasal tip to the rhinion: the anterior tip of the terminal end of the nasal-bone suture.

- Posterior ethmoid nerve – serves the superior (upper) half of the nasal cavity, the sphenoids, and the ethmoids.

- Intratrochlear nerve – conveys sensation to the medial region of the eyelids, the palpebral conjunctiva, the nasion (nasolabial junction), and the bony dorsum.

- The maxillary division innervation

- Maxillary nerve – conveys sensation to the upper jaw and the face.

- Infraorbital nerve – conveys sensation to the area from below the eye socket to the external nares (nostrils).

- Zygomatic nerve – through the zygomatic bone and the zygomatic arch, conveys sensation to the cheekbone areas.

- Superior posterior dental nerve – sensation in the teeth and the gums.

- Superior anterior dental nerve – mediates the sneeze reflex.

- Sphenopalatine nerve – divides into the lateral branch and the septal branch, and conveys sensation from the rear and the central regions of the nasal cavity.

The supply of parasympathetic nerves to the face and the upper jaw (maxilla) derives from the greater superficial petrosal (GSP) branch of cranial nerve VII, the facial nerve. The GSP nerve joins the deep petrosal nerve (of the sympathetic nervous system), derived from the carotid plexus, to form the vidian nerve (in the vidian canal) that traverses the pterygopalatine ganglion (an autonomic ganglion of the maxillary nerve), wherein only the parasympathetic nerves form synapses, which serve the lacrimal gland and the glands of the nose and of the palate, via the (upper jaw) maxillary division of cranial nerve V, the trigeminal nerve.

Internal nasal anatomy

In the midline of the nose, the septum is a composite (osseo-cartilaginous) structure that divides the nose into two (2) similar halves. The lateral nasal wall and the paranasal sinuses, the superior concha, the middle concha, and the inferior concha, form the corresponding passages, the superior meatus, the middle meatus, and the inferior meatus, on the lateral nasal wall. The superior meatus is the drainage area for the posterior ethmoid bone cells and the sphenoid sinus; the middle meatus provides drainage for the anterior ethmoid sinuses and for the maxillary and frontal sinuses; and the inferior meatus provides drainage for the nasolacrimal duct.

The internal nasal valve comprises the area bounded by the upper lateral-cartilage, the septum, the nasal floor, and the anterior head of the inferior turbinate. In the narrow (leptorrhine) nose, this is the narrowest portion of the nasal airway. Generally, this area requires an angle greater than 15 degrees for unobstructed breathing; for the correction of such narrowness, the width of the nasal valve can be increased with spreader grafts and flaring sutures.

Development

At four (4) weeks of gestational development, the neural crest cells (the precursors of the nose) begin their caudad migration (from the posterior) towards the midface. Two symmetrical nasal placodes (the future olfactory epithelium) develop inferiorly, which the nasal pits then divide into the medial and the lateral nasal processes (the future upper lip and nose). The medial processes then form the septum, the philtrum, and the premaxilla of the nose; the lateral processes form the sides of the nose; and the mouth forms from the stomodeum (the anterior ectodermal portion of the alimentary tract), which is inferior to the nasal complex.

A nasobuccal membrane separates the mouth from the nose; respectively, the inferior oral cavity (the mouth) and the superior nasal cavity (the nose). As the olfactory pits deepen, said development forms the choanae, the two openings that connect the nasal cavity and the nasopharynx (upper part of the pharynx that is continuous with the nasal passages). Initially, primitive-form choanae develop, which then further develop into the secondary, permanent choanae.

At ten (10) weeks of gestation, the cells differentiate into muscle, cartilage, and bone. If this important, early facial embryogenesis fails, it might result in anomalies such as choanal atresia (absent or closed passage), medial nasal clefts (fissures), or lateral nasal clefts, nasal aplasia (faulty or incomplete development), and polyrrhinia (double nose).[5]

This normal, human embryologic development is exceptionally important — because the newborn infant breathes through his or her nose during the first 6 weeks of life — thus, when a child is afflicted with bilateral choanal atresia, the blockage of the posterior nasal passage, either by abnormal bony tissue or by abnormal soft tissue, emergency remedial action is required to ensure that the child can breathe.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste de Panafieu, P. (2007). Evolution. Seven Stories Press, USA.

- ↑ archaeologyinfo.com > glossary Retrieved on August 2010

- ↑ Heidari Z, Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb H, Khammar T, Khammar M (May 2009). "Anthropometric measurements of the external nose in 18–25-year-old Sistani and Baluch aborigine women in the southeast of Iran". Folia Morphol. (Warsz). 68 (2): 88–92. PMID 19449295.

- ↑ Fattahi TT (October 2003). "An overview of facial aesthetic units". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 61 (10): 1207–11. PMID 14586859. doi:10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00684-0.

- ↑ Hengerer AS, Oas RE (1987). Congenital Anomalies of the Nose: Their Embryology, Diagnosis, and Management (SIPAC). Alexandria VA: American Academy of Otolaryngology.

- ↑ Nasal Anatomy at eMedicine