Leonardo Drew

| Leonardo Drew | |

|---|---|

| Born |

1961 Tallahassee, Florida, US |

| Known for | Sculptures |

| Website | leonardodrew.com |

Leonardo Drew is an African American contemporary artist based in Brooklyn, New York. He creates sculptures from natural materials and through processes of oxidation, burning, and decay, Drew transforms these objects into massive sculptures that critique social injustices and the cyclical nature of existence.

Early life

Leonardo Drew was born in Tallahassee, Florida, but was raised in the projects of Bridgeport, Connecticut, where the city dump occupied every view of his apartment. During his early childhood, Drew often found himself there mining through and creating works from discarded remnants, giving them new meaning. [1] In Existed, “Dust to Dust by Allen S. Weiss, Drew stated, “ I remember all of it, the seagulls, the summer smells, the underground fires that could not be put out… and over time I came to realize this place as ‘God’s mouth’…the beginning and the end…and the beginning again [sic]… Though I do not use found objects in my work (my materials are fabricated in the studio) what has remained from my early explorations are the echoes of evolution…life, death, regeneration.”

Career

Leonardo began his artistic career at a very young age, exhibiting his work publicly for the first time at the age of 13. His initial work in drawing drew the attention of talent scouts from DC Comics, Marvel Comics and Heavy Metal magazine. [2] After being introduced to abstraction through reproductions of works by artists like Jackson Pollock and receiving inspiration from the process-based work of post-war American and European artists, Drew decided to focus on his fine arts training and immersed himself in exploring his own sense of abstraction. He then went on to attend Parsons School of Design in New York, and received his BFA from Cooper Union in 1985.

His works are part of several major public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; The Tate, United Kingdom; The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY; Saint Louis Museum, Saint Louis, MO; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA; and Pérez Art Museum Miami in Miami, FL.[3] He has also collaborated with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, on a production entitled 'Ground Level Overlay,'[4] and has participated in several artist residencies including those at ArtPace, San Antonio and The Studio Museum of Harlem in New York, among others.[5]

Work

In 1988, Leonardo Drew found his artistic voice when creating his seminal work Number 8, which he believes begat everything that followed.[6] It was made of wood, paper, rope, feathers, animal hides, dead birds and skeletal remains.[7] Number 8 was first exhibited at Kenkeleba House in New York City in 1989 where it was "immediately recognized as an aggressive assertion of an artistic identity wrought from personal experience and cultural heritage."[8] Its ominous allure embodies "the cyclical nature of existence," a reality that reveals the resonance of life, the "nature of nature," a theme that is still prevalent in all of his work.

In the early 1990s, Drew began to incorporate the element of rust in many of works by producing it chemically in the studio as well as using collected pieces of scrap metal collected from the streets of New York. These early works from the 1990s were exhibited in several spaces including The Carnegie International. In 1992, Drew had his first major solo exhibition at the Thread Waxing Space in New York, which included a published catalogue with an essay written by writer and critic Hilton Als. The exhibition included many large-scale abstract sculptures made from various materials including wood, rust and cotton.

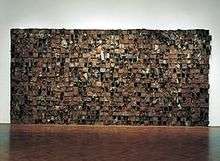

Later on that year, Drew was invited to display work in the Senegal biennial. During his time in Africa, he visited an African slave trading post. Viewing the catacombs and dungeons, he realized first hand of the "horrific and claustrophobic conditions"[9] that captured Africans had to endure before being shipped out to a life of enslavement. This experience deeply affected the execution and meaning of his work. Number 43 is an example of one of the sculptures he created after visiting Africa. The repetition of hundreds of closely packed rust-encrusted boxes filled with rags and debris referencing and symbolizing the horrid living conditions of the slave.

New York Times art critic Roberta Smith describes his large reliefs as “ pocked, splintered, seemingly burned here, bristling there, unexpectedly delicate elsewhere. An endless catastrophe seen from above. The energies intimated in these works are beyond human control, bigger than all of us”[10] Drew is known for creating reflective abstract sculptural works that play upon the dystopic tension between order and chaos.[11] Leonardo Drew’s work is reminiscent of Post Minimalist sculpture that alludes to America’s industrial past. The materials also reference the plight of African Americans in U.S. history.[12] One could find many meanings in his work, but it seems that he is ultimately concerned with the cyclical nature of life and decay, which can be seen in the grid and the transformation of raw material - lumber, steel, canvas, paper - to resemble debris.[13] This method generates an articulation of entropy and a visual erosion of time.

The mid-career survey exhibition, Existed: Leonardo Drew, was inaugurated in 2009 at the Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston and later traveled to the Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, NC and the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park in Lincoln, MA. A monograph of his work was published in conjunction with the exhibition by Giles, Ltd., London, with critical essays written by museum director and curator Claudia Schmuckli and professor and cultural historian, Allen S. Weiss.[3]

In 2012, Drew had his fourth solo exhibition at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. in New York that included the publication of a catalogue that chronicles his artistic production from 2007 to 2012 produced by Charta Books.[14] The exhibition featured several large scale installations and works that have been described as imbued with "the kind of energetic core typical of many of Drew's sculptures, as is the blurring of distinctions between what's swallowing or bursting from what's natural or constructed."[15]

Selected Solo Exhibitions

- 2013: Selected Works, Savannah College of Art and Design Museum, GA; Canzani Center Gallery at Columbus College of Art and Design, Ohio; VIGO Gallery, London, UK.

- 2012: Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY

- Pace Prints, New York, NY

- 2011: Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA

- VIGO Gallery, London, UK

- Galleria Napolinobilissima, Naples, Italy

- 2010: Window Works: Leonardo Drew, Artpace, San Antonio, TX

- 2009: Existed: Leonardo Drew, Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston, TX: May 16- August 15, 2009; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC: Feb. 6 – May 9, 2010; DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln, MA: September 18, 2010 – January 9, 2011

- 2007: Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY

- 2006: Palazzo Delle Papesse, Centro Arte Contemporanea, Siena, Italy

- Brent Sikkema, New York, NY

- The Fabric Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

- 2001: Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY

- Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin, Ireland

- 2000: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

- The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, NY

- Madison Art Center, Madison, WI

- 1998: Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY

- 1997: Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

- 1996: University at Buffalo Art Gallery, Center for the Arts, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY; Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY

- 1995: Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA

- The Pace Roberts Foundation for Contemporary Art, San Antonio, TX

- Ground Level Overlay, Merce Cunningham Dance Company Collaboration, New York, NY

- 1994: San Francisco Art Institute, Walter/Mc Bean Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

- 1992: Thread Waxing Space, New York, NY

See also

- Inside the Artist's Studio, Princeton Architectural Press, 2015. (ISBN 978-1616893040)

References

- ↑ "A Trash Course In Sculpture". Washingtonpost.com. 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ "Viewing Life's Decay". Washingtonpost.com. 2000-03-26. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- 1 2 On View Sep 18, 2010 - Jan 09, 2011. "Existed: Leonardo Drew". deCordova. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ "On View: Emotionally Charged Abstraction by Leonardo Drew". Arts Observer. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "The Artist’s Voice: Leonardo Drew | The Studio Museum in Harlem". Studiomuseum.org. 2012-04-12. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ "Blaffer’s Leonardo Drew survey hits a home run". Houston Chronicle. 2009-07-12. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ "Viewing Life's Decay". The Boston Globe. 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ Schmuckli, Claudia, "Being and Somethingness," Existed: Leonardo Drew, D Giles Limited, 2009.

- ↑ [http://www.mutualart.com/OpenArticle/Beauty-in-the-Abandoned/E58B7C842CD62DE1> "Beauty in the Abandoned"]. Mutual Art. 2009-07-16. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ "Swagger and Sideburns: Bad Boys in Galleries". New York Times. 2010-02-11. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ Fishman, George. "PAMM, Virginia Miller exhibits explore abstraction - Visual Arts". MiamiHerald.com. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "North South East West" (PDF). Chateau DuBois. 2010-02-11. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ↑ "/ critics' picks". Artforum.com. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ Ebony, David (2013-01-18). "Leonardo Drew - Reviews - Art in America". Artinamericamagazine.com. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ Proenza, Mary. "Leonardo Drew," Art in America, January 18, 2013.

External links

- Leonardo Drew artist website

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Corcoran Gallery of Art

- ArtSlant

- The Fabric Workshop and Museum