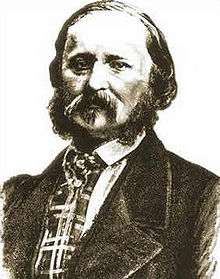

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville

| Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville | |

|---|---|

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville | |

| Born | 25 April 1817 |

| Died | 26 April 1879 (aged 62) |

| Residence | Paris |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Inventing the earliest known sound recording device |

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville (25 April 1817 – 26 April 1879) was a French printer and bookseller who lived in Paris.

He invented the earliest known sound recording device, the phonautograph, which was patented in France on 25 March 1857.[1][2][3]

Early years

As a printer by trade, he was able to read accounts of the latest scientific discoveries and became an inventor. Scott de Martinville was interested in recording the sound of human speech in a way similar to that achieved by the then new technology of photography for light and image. He hoped for a form of stenography that could record the whole of a conversation without any omissions. His earliest interest was in an improved form of stenography and he was the author of several papers on shorthand and a history of the subject (1849).[4]

Phonautograph

From 1853 he became fascinated in a mechanical means of transcribing vocal sounds. While proofreading some engravings for a physics textbook he came across drawings of auditory anatomy. He sought to mimic the working in a mechanical device, substituting an elastic membrane for the tympanum, a series of levers for the ossicle, which moved a stylus he proposed would press on a paper, wood, or glass surface covered in lampblack. On 26 January 1857, he delivered his design in a sealed envelope to the French Academy.[4] On 25 March 1857, he received French patent #17,897/31,470 for the phonautograph.

The phonautograph used a horn to collect sound, attached to a diaphragm which vibrated a stiff bristle which inscribed an image on a lamp black coated, hand-cranked cylinder. Scott built several devices with the help of acoustic instrument maker Rudolph Koenig. Unlike Edison's later invention of 1877, the phonograph, the phonautograph only created visual images of the sound and did not have the ability to play back its recordings. Scott de Martinville's device was used only for scientific investigations of sound waves.

Scott de Martinville managed to sell several phonautographs to scientific laboratories for use in the investigation of sound. It proved useful in the study of vowel sounds and was used by Franciscus Donders, Heinrich Schneebeli and Rene Marage. It also initiated further research into tools able to image sound such as Koenig's manometric flame.[4] He was not, however, able to profit from his invention and spent the remainder of his life as a librarian and bookseller at 9 Rue Vivienne in Paris.

Scott de Martinville also became interested in the relationship between linguistics, people's names and their character and published a paper on the subject (1857).[4]

Rediscovery of the Au clair de la lune recording

|

Au clair de la lune

Speed and pitch corrected to reflect Scott's voice. |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

In 2008, The New York Times reported the playback of a phonautogram recorded on 9 April 1860.[7] The recording was converted from "squiggles on paper" to a playable digital audio file by scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California.[7] The phonautogram was one of several deposited by Léon Scott in two archives in Paris and only recently brought to light.

The recording, of part of the French folk song Au clair de la lune, was initially played at a speed that produced what seemed to be a 10-second recording of the voice of a woman or child singing at an ordinary musical tempo. The researchers leading the project later found that a misunderstanding about an included reference frequency had resulted in a doubling of the correct playback speed, and that it was actually a 20-second recording of a man, probably Scott himself, singing the song very slowly.[8] It is now the earliest known recording of singing in existence, predating, by 28 years, several 1888 Edison wax cylinder phonograph recordings of a massed chorus performing Handel's oratorio Israel in Egypt.[9]

A phonautogram by Scott containing the opening lines of Torquato Tasso's pastoral drama Aminta, in Italian, has also been found. Recorded around 1860, probably after the recording of Au clair de la lune, this phonautogram is now the earliest known recording of intelligible human speech.[10] Recordings of Scott's voice made in 1857 have also survived, but they are only unintelligible snippets.

It has been claimed that in 1863 Scott's phonautograph was used to make a recording of Abraham Lincoln's voice at the White House.[11] A phonautogram of Lincoln's voice was supposedly among the artifacts kept by Thomas Edison. According to FirstSounds.org, these stories are variations of a myth that seems to have first appeared in print in a 1969 book about antique collecting, in which it is explicitly categorized as a legend and dismissed as based on "garbled accounts".[12] There is no solid evidence that such a recording ever existed.[12] The most nearly similar artifact known to have been kept by Edison was a recording of the voice of President Rutherford B. Hayes, captured as a groove indented into a sheet of tinfoil when Edison demonstrated his newly-invented phonograph to Hayes in 1878. Scott did not visit the US in the 1860s and therefore could not have recorded Lincoln himself, as one version of the legend claims he did.[12]

Scott's phonautograms were selected by the Library of Congress as a 2010 addition to the National Recording Registry, which selects recordings annually that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[13]

Publications

- Jugement d'un ouvrier sur les romans et les feuilletons à l'occasion de Ferrand et Mariette (1847)

- Histoire de la sténographie depuis les temps anciens jusqu'à nos jours (1849)

- Les Noms de baptême et les prénoms (1857)

- Fixation graphique de la voix (1857)

- Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. Adolphe-Noël Desvergers

- Essai de classification méthodique et synoptique des romans de chevalerie inédits et publiés. Premier appendice au catalogue raisonné des livres de la bibliothèque de M. Ambroise Firmin-Didot (1870)

- Le Problème de la parole s'écrivant elle-même. La France, l'Amérique (1878)

References

- ↑ Schoenherr, Steven E. "Leon Scott and the Phonautograph.". Retrieved 2008-03-27.

Edouard-Leon Scott de Martinville was born in France in 1817.

- ↑ "Oldest recorded voices sing again.". BBC. 28 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

An "ethereal" 10 second clip of a woman singing a French folk song has been played for the first time in 150 years. The recording of "Au Clair de la Lune", recorded in 1860, is thought to be the oldest known recorded human voice.

- ↑ "Sound Recording Predates Edison Phonograph". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

He invented a device called the phonautograph, and, on 9 April 1860, recorded someone singing the words, 'Au clair de la lune, Pierrot repondit [sic].' But he never had any intention of playing it back. He just wanted to study the pattern the sound waves made on a sheet of paper blackened by the smoke of an oil lamp.

- 1 2 3 4 Hankins, Thomas L.; Robert J. Silverman (1995). Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton University Press. pp. 133 to 135. ISBN 0-691-00549-4.

- ↑ "FirstSounds.ORG".

- ↑ http://www.firstsounds.org/sounds/1860-Scott-Au-Clair-de-la-Lune-05-09.ogg

- 1 2 Rosen, Jody (27 March 2008). "Researchers Play Tune Recorded Before Edison.". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

The audio excavation could give a new primacy to the phonautograph, once considered a curio, and its inventor, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, a Parisian typesetter and tinkerer who went to his grave convinced that credit for his breakthroughs had been improperly bestowed on Edison.

- ↑ "Earliest Known Sound Recordings Revealed". US News & World Report.

- ↑ The 1888 Crystal Palace recordings

- ↑ Cowen, Ron (June 1, 2009). "Earliest Known Sound Recordings Revealed Researchers unveil imprints made 20 years before Edison invented phonograph". Science News. U.S.News & World Report. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ Hafner, Katie (March 25, 1999). "In Love With Technology, as Long as It's Dusty". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

In 1863, nearly 15 years before Thomas Alva Edison created the first phonograph, an inventor named Leon Scott is said to have visited the White House. If historical anecdotes are accurate, he made a tracing of President Lincoln's voice with his newly invented 'phonautograph,' a machine that scratched sound patterns onto a soot-blackened sheet of paper wrapped around a drum.

- 1 2 3 "The 'Lost' Tracing of Lincoln's Voice". FirstSounds.org. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ↑ "The National Recording Registry 2010". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

Further reading

- Helmholtz, Hermann. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. Translated by Alexander J. Ellis. London: Longmans, Green, 1875, p. 20.

- History of the Phonautograph Marco, Guy A., editor. Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound in the United States. New York: Garland, 1993, p. 615.

- Winston, Brian. Media Technology and Society: a History from the Telegraph to the Internet. New York : Routledge, 1998.

External links

- FirstSounds.org, including The Phonautographic Manuscripts of Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville (PDF)