Leo Marchutz

| Leo Marchutz | |

|---|---|

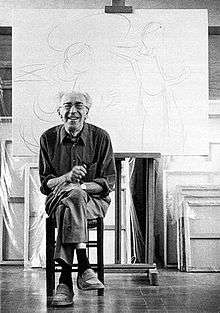

In his studio in Aix, 1974 | |

| Born |

Leo Marchutz August 29, 1903 Nuremberg, Germany |

| Died |

January 4, 1976 Aix-en-Provence |

| Nationality | German, French |

| Education | Self-taught |

| Known for | Drawing, Painting, Lithography |

| Notable work | L'Evangile Selon Saint Luc (1949) |

| Patron(s) | Fernand Pouillon |

Leo Marchutz (1903–1976) was a German painter, lithographer, and art educator.

Life

Early years

Marchutz was born in Nuremberg, Germany on August 29, 1903. He began painting at the age of thirteen and soon rejected the formal training of several instructors. Instead, he embarked on an independent study of masterpieces in the museums of Nuremberg and Berlin, where he first encountered the work of Van Gogh and Cézanne.

He completed his first album of lithographs in 1924, based on Plato's Symposium. In the same year, he held his first solo exhibition at the home of prominent collector Karl-Ernst Osthaus. By 1925, he had sold works to several other collectors, including the director Max Reinhardt.[1]

Throughout the 1920s, he travelled to several cities in Germany and Italy, where he worked from outdoor motifs, from memory, and from his imagination. At every opportunity, he continued his practice of looking carefully at masterpieces in museums.

Most of his paintings from this early period have been lost; only a photograph of the Reinhardt picture (the Ascension) remains.

Aix-en-Provence

Recognizing a kindred spirit in Cézanne, Marchutz took an initial trip to the artist's native Aix-en-Provence, France in the summer of 1928 and emigrated there permanently in 1931. For the next three and a half decades, he worked and resided at the Chateau Noir, a Provençal farmhouse several kilometers east of town.

From 1934 to 1944, he earned his living as a poultry farmer, raising chickens in specially-constructed sheds on the grounds of Chateau Noir.

Because he was a German national living in France, Marchutz was placed in an internment camp in Les Milles in September 1939. Under an agreement to serve as a prestataire in the French army, he was released in February 1940 and called into service in May of the same year. Having been demobilized at the beginning of October, he moved back into the Chateau Noir, where he would spend the rest of the war in hiding. Due to the difficulties of enduring this period, he only produced small drawings on poor-quality paper. After the war, however, Marchutz reapplied himself to drawing and painting, in addition to developing a unique method of producing lithographs which he would refine for the rest of his life.

In 1954, the architect Fernand Pouillon became a patron, and in 1957, designed and dedicated a studio to the artist. Marchutz worked there continually for the rest of his life, and upon its completion in 1968, moved into the adjacent apartment.

The Institute for American Universities, an organization aimed at enabling American students to study abroad in France, hired him in 1959 to teach studio art classes. In 1972, he founded the Marchutz School of Painting and Drawing with former students William Weyman and Samuel Bjorklund. Here he taught students such as Gene Hatfield, a celebrated artists from the United States. The school exists to this day.

Parallel to his own artistic endeavor, Marchutz became a specialist in the works of Cézanne and maintained close relationships with major art historians and scholars, including John Rewald, Lionello Venturi, Fritz Novotny, and Adrien Chappuis. Both Rewald and Chappuis consulted him in preparing their catalogues of Cézanne's oeuvre, and Marchutz co-authored and published several articles with Rewald, including a photographic study of Cézanne's motifs.[2][3] Marchutz also played a central role in organizing the first major Cézanne exhibition in Aix, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the artist's death, as well as a second exhibition held in 1961.

Marchutz died on January 4, 1976 in Aix. His work can be found today in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre, the Musee Granet in Aix, and in numerous other museums and private collections around the world.

Artistic Development

Even at an early age, Marchutz concerned himself with spiritual subject matter, and his first forays into painting and lithography already display several characteristics that would become prominent in his later work. Writing about a painting he had purchased, Max Reinhardt noted that "the principal agreement of the picture resides in the happy simplification and the configuration of the figures between themselves."[4] Marcel Ruff, writing about another painting from this period, saw "nothing showy in the treatment, but a freshness, an unusual purity."[5]

Beginning in 1924, Marchutz embarked on several trips to Venice, Florence, and Rome, where he drew from architectural motifs and studied paintings in museums.

Upon his first arrival in Aix in 1928, Marchutz primarily painted landscapes. Three years later, after permanently relocating, he spent much of his time executing drawings of the town's streets, while continuing to produce paintings of the surrounding countryside. The outbreak of World War II soon forced him to abandon those efforts. For most of the following six years, he took occasional breaks from his poultry-farming chores to execute drawings of human figures in pencil, usually inspired by his reading of passages from the New Testament. The simplicity of the medium and of the drawings themselves would have a profound effect on his later work.

Emerging from the interruption that the war had demanded, Marchutz slowly assembled a volume of lithographs, L'Evangile Selon Saint Luc. The work was published in 1949 with a preface by art historian Lionello Venturi. Venturi wrote that "the images created by the artist appear on these pages as though revealed in the atmosphere, borne by a wind which, some time ago, was called astonishment."[6] He also noted that Marchutz "sees by volume and not by contours."[6]

During the 1950s, Marchutz continued to refine his approach to lithography, producing works based mainly on architectural and landscape motifs in Aix and Venice. By 1964, he had completed an album of lithographs depicting one of Cézanne's most celebrated motifs—Mont Sainte Victoire. This type of landscape motif, as well as religious figures from the earlier periods, would dominate his work over the next decade and a half.

Georges Duby, in 1962, observed that Marchutz

expels little by little all which is not essential to the image. He grasps by the one necessary stroke the quickness of the flash of an eye when it is a question of illustrating the Gospel of St. Luke. He achieves in the same way, before a landscape, the fundamentals of mass, light and color between air, ground and buildings, and finally, at the end of a patiently followed road, arrives at an extreme purity. That which moves one, at the heart of Marchutz’s art, is a rare spiritual exigence, a strong will for asceticism.[7]

At the same time, John Rewald noted that Marchutz "reduces the elements of reality to their most essential signs...[and] hovers on the border of abstraction though never abandoning the sharp observation of his subject." He also remarked on Marchutz's ability to "create images where a few delicate hues evoke sites or figures, the economy of means leading him towards a sort of poetry of suggestion whose starting point is nature and whose result is our enchantment."[8]

Inspired by a commission for the University of Nice in 1963, Marchutz began to create larger works, often based on earlier, smaller drawings. The subjects of these canvasses were typically religious, most often a configuration of figures inspired by a passage from the Gospels. These larger, mural-like paintings represent the final stage of his art and the bulk of his output in the 1970s.

Above all, the guiding principle in Marchutz's artistic development was his desire to "stay in the line";[9] the "line" to which he refers is what he saw as the unbroken connection between artists of every century, stretching back even to the cave painters of Lascaux and Altamira. The qualities of distance, volume, and light were essential to his art, and, he believed, to every other artist's as well.

Notes

- ↑ de Asis, Leo Marchutz, p. 251.

- ↑ Rewald, in Cézanne: The Late Work, pp. 105-6.

- ↑ Rewald and Marchutz, "Cézanne au Chateau Noir," pp. 15-21.

- ↑ Reinhardt, Letter to Marchutz, June 27, 1919; see also .

- ↑ Ruff, Leo Marchutz.

- 1 2 Marchutz, L'Evangile.

- ↑ Duby, Introduction to catalogue, 1962.

- ↑ Rewald, Letter dated May 14, 1962, published in the catalogue for Marchutz's exhibition at the Tony Spinazzola Gallery, Aix-en-Provence, July 1962.

- ↑ de Asis, Leo Marchutz, p. 237.

References

- de Asis, Francois and Antony Marschutz. Leo Marchutz, Painter and Lithographer, 1903-1976. Marseille, Editions Imbernon, 2006.

- Duby, Georges. Introduction to the catalogue for Marchutz's exhibition at the Tony Spinazzola Gallery, Aix-en-Provence, July 1962.

- Marchutz, Leo. L'Evangile Selon Saint Luc. Aix-en-Provence, 1949.

- Rewald, John. "The Last Motifs at Aix," in Cézanne: The Late Work, William Rubin, ed., New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1977.

- Rewald, John and Leo Marchutz. "Cézanne au Chateau Noir" in L'Amour de l'Art, January 1935, pp. 15–21.

- Ruff, Marcel. "Leo Marchutz", in the review L’Arc, number 3, Aix-en-Provence, July 1958.