Lentivirus

| lentivirus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group VI (ssRNA-RT) |

| Order: | Unassigned |

| Family: | Retroviridae |

| Subfamily: | Orthoretrovirinae |

| Genus: | Lentivirus |

| Type species | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus 1 | |

| Species | |

|

Bovine lentivirus group Equine lentivirus group Feline lentivirus group

Colugo lentivirus group

Weasel lentivirus group

Rabbit lentivirus group

Ovine/caprine lentivirus group Primate lentivirus group

| |

Lentivirus (lente-, Latin for "slow") is a genus of retroviruses that cause chronic and deadly diseases characterized by long incubation periods, in the human and other mammalian species.[1] The best known lentivirus is the Human Immunodeficiency Virus HIV, which causes AIDS. Lentiviruses are also hosted in apes, cows, goats, horses, cats, and sheep.[1] Recently, lentiviruses have been found in monkeys, lemurs, Malayan flying lemur (not a true lemur nor a primate), rabbits, and ferrets. Lentiviruses and their hosts have worldwide distribution. Lentiviruses can integrate a significant amount of viral RNA into the DNA of the host cell and can efficiently infect nondividing cells, so they are one of the most efficient methods of gene delivery.[2] Lentiviruses can become endogenous (ERV), integrating their genome into the host germline genome, so that the virus is henceforth inherited by the host's descendants.

Classification

Five serogroups of lentiviruses are recognized, reflecting the vertebrate hosts with which they are associated (primates, sheep and goats, horses, domestic cats, and cattle).[3] The primate lentiviruses are distinguished by the use of CD4 protein as a receptor and the absence of dUTPase.[4] Some groups have cross-reactive gag antigens (e.g., the ovine, caprine, and feline lentiviruses). Antibodies to gag antigens in lions and other large felids indicate the existence of other as yet unidentified viruses related to feline lentivirus and the ovine/caprine lentiviruses.

Morphology

The virions are enveloped, slightly pleomorphic, spherical and measure 80–100 nm in diameter. Projections of envelope make the surface appear rough, or tiny spikes (about 8 nm) may be dispersed evenly over the surface. The nucleocapsids (cores) are isometric. The nucleoids are concentric and rod-shaped, or shaped like a truncated cone.[5]

Genome organization and replication

Features of the genome: infectious viruses have three main genes coding for the viral proteins in the order: 5´-gag-pol-env-3´. There are two regulatory genes, tat and rev. There are additional accessory genes depending on the virus (e.g., for HIV-1: vif, vpr, vpu, nef) whose products are involved in regulation of synthesis and processing viral RNA and other replicative functions. The Long terminal repeat (LTR) is about 600 nt long, of which the U3 region is 450, the R sequence 100 and the U5 region some 70 nt long.

Viral proteins involved in early stages of replication include reverse transcriptase and integrase. Reverse transcriptase is the virally encoded RNA-dependent DNA polymerase. The enzyme uses the viral RNA genome as a template for the synthesis of a complementary DNA copy. Reverse transcriptase also has RNaseH activity for destruction of the RNA-template. Integrase binds both the viral cDNA generated by reverse transcriptase and the host DNA. Integrase processes the LTR before inserting the viral genome into the host DNA. Tat acts as a trans-activator during transcription to enhance initiation and elongation. The Rev responsive element acts post-transcriptionally, regulating mRNA splicing and transport to the cytoplasm.[6]

Proteome

The lentiviral proteome consists of five major structural proteins and 3-4 non-structural proteins (3 in the primate lentiviruses).

Structural proteins listed by size:

- Gp120 surface envelope protein SU, encoded by the viral gene env. 120000 Da (Daltons).

- Gp41 transmembrane envelope protein TM, also encoded by the viral gene env. 41000 Da.

- P24 capsid protein CA, encoded by the viral gene gag. 24000 Da.

- P17 matrix protein MA, also encoded by gag. 17000 Da.

- P9 capsid protein NC, also encoded by gag. 7000-11000 Da.

- The envelope proteins SU and TM are glycosylated in at least some lentiviruses (HIV, SIV), if not all of them. Glycosylation seems to play a structural role in the concealment and variation of antigenic sites necessary for the host to mount an immune system response.

Enzymes:

- Reverse transcriptase RT encoded by the pol gene. Protein size 66000 Da.

- Integrase IN also encoded by the pol gene. Protein size 32000 Da.

- Protease PR encoded by the pro gene.

- dUTPase DU encoded by the pro gene (part of pol gene in some viruses), the role of which is still unknown. Protein size 14000 Da.

Gene regulatory proteins:

- Tat

- Rev

Accessory proteins:

- Nef

- Vpr

- Vif

- Vpu/Vpx

- p6

Antigenic properties

Serological Relationships: Antigen determinants are type-specific and group-specific. Antigen determinants that possess type-specific reactivity are found on the envelope. Antigen determinants that possess type-specific reactivity and are involved in antibody mediated neutralization are found on the glycoproteins. Cross-reactivity has been found among some species of the same serotype, but not between members of different genera. Classification of members of this taxon is infrequently based on their antigenic properties.

Epidemiology

- Symptoms and host range: The virus' hosts are found in the orders Primates (humans, apes and monkeys), Carnivora (cats, dogs and other carnivores), Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla (single and double-toed hooved mammals).

- Transmission: Transmitted by means not involving a vector.

- Geographic distribution: Worldwide.

Physicochemical and physical properties

- General

- Buoyant density 1.16–1.18 g cm−3 in sucrose

- Virions sensitive to heat, detergents, and formaldehyde

- Infectivity not affected by UV irradiation

Classed as having class C morphology

- Nucleic Acid

- Virions contain 2% nucleic acid

- Genome consists of a dimer

- Virions contain one molecule of (each) linear positive-sense single stranded RNA.

- Total genome length is of one monomer 9200 nt

- Genome sequence has terminal repeated sequences; long terminal repeats (LTR) (of about 600 nt)

- The 5' end of the genome has a cap

- Cap sequence of type 1 m7G5ppp5'GmpNp

- 3' end of each monomer has a poly (A) tract; 3'-terminus has a tRNA-like structure (and accepts lysin)

- Encapsidated nucleic acid are solely genomic

- 2 copies packed per particle (held together by hydrogen bonds to form a dimer).

- There are 11 proteins

- Virions contain 60% protein

- Five (major)structural virion proteins have been found so far

- Lipids: Virions contain 35% lipid.

- Carbohydrates: Other compounds detected in the particles 3% carbohydrates.

Use as gene delivery vectors

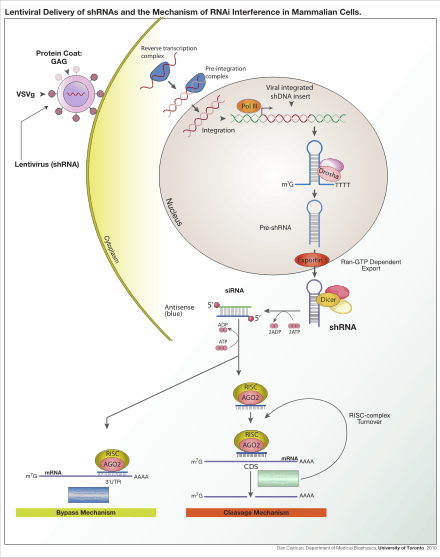

Lentivirus is primarily a research tool used to introduce a gene product into in vitro systems or animal models. Large-scale collaborative efforts are underway to use lentiviruses to block the expression of a specific gene using RNA interference technology in high-throughput formats.[7] The expression of short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) reduces the expression of a specific gene, thus allowing researchers to examine the necessity and effects of a given gene in a model system. These studies can be a precursor to the development of novel drugs which aim to block a gene-product to treat diseases. Conversely, lentivirus are also used to stably over-express certain genes, thus allowing researchers to examine the effect of increased gene expression in a model system.

Another common application is to use a lentivirus to introduce a new gene into human or animal cells. For example, a model of mouse hemophilia is corrected by expressing wild-type platelet-factor VIII, the gene that is mutated in human hemophilia.[8] Lentiviral infection has advantages over other gene-therapy methods including high-efficiency infection of dividing and non-dividing cells, long-term stable expression of a transgene, and low immunogenicity. Lentiviruses have also been successfully used for transfection of diabetic mice with the gene encoding PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor),[9] a therapy being considered for use in humans. These treatments, like most current gene therapy experiments, show promise but are yet to be established as safe and effective in controlled human studies. Gammaretroviral and lentiviral vectors have so far been used in more than 300 clinical trials, addressing treatment options for various diseases.[10]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "What is Lentivirus?". News-Medical.net. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ Cockrell, Adam S.; Kafri, Tal (2007-07-01). "Gene delivery by lentivirus vectors". Molecular Biotechnology. 36 (3): 184–204. ISSN 1073-6085. PMID 17873406. doi:10.1007/s12033-007-0010-8.

- ↑ Mahy, Brian W. J. (2009-02-26). The Dictionary of Virology. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080920368.

- ↑ Piguet, V.; Schwartz, O.; Le Gall, S.; Trono, D. (1999-04-01). "The downregulation of CD4 and MHC-I by primate lentiviruses: a paradigm for the modulation of cell surface receptors". Immunological Reviews. 168: 51–63. ISSN 0105-2896. PMID 10399064. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01282.x.

- ↑ "ViralZone: Lentivirus". viralzone.expasy.org. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ Gilbert, James R., and Flossie Wong-Staal. "HIV-2 and SIV Vector Systems." Lentiviral Vector Systems for Gene Transfer. Ed. Gary L. Buchschacher. Georgetown, TX: Eurekah.com, 2003. https://books.google.com/books?id=59FuGsgsI5wC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ shRNA – short hairpin RNA

- ↑ Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Fahs SA, et al. (February 2007). "Lentivirus-mediated platelet-derived factor VIII gene therapy in murine haemophilia A". J. Thromb. Haemost. 5 (2): 352–61. PMID 17269937. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02346.x.

- ↑ Lee JA, Conejero JA, Mason JM, et al. (August 2005). "Lentiviral transfection with the PDGF-B gene improves diabetic wound healing". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 116 (2): 532–8. PMID 16079687. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000172892.78964.49.

- ↑ Kurth, R; Bannert, N, eds. (2010). Retroviruses: Molecular Biology, Genomics and Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-55-4.

References

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases (4th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- Desport, M, ed. (2010). Lentiviruses and Macrophages: Molecular and Cellular Interactions. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-60-8.

Further reading

- ICTV taxonomy of Lentivirus

- "Lentiviruses In Ungulates. I. General Features, History And Prevalence" (PDF). Bulgarian Journal of Veterinary Medicine. 9 (3): 175–181. 2006.

- Tim Ravenscroft (2008-06-15). "Are Lentiviral Vectors on Cusp of Breakout?". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. pp. 54–55. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

(subtitle) Rapidly emerging technology has potential to treat hemophilia, AIDS, and Cancer