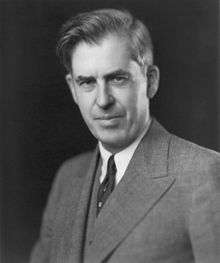

Len De Caux

| Len De Caux | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Leonard Howard DeCaux October 14, 1899 Westport, New Zealand |

| Died | May 24, 1991 (aged 91) |

| Other names | Leonard De Caux, Len DeCaux |

| Years active | 1921–1965 |

| Organization | FP, CIO |

| Known for | Pro-labor publicity |

| Political party | CPUSA |

| Movement | Labor |

| Opponent(s) | NAM, Walter Reuther |

| Spouse(s) | Caroline Abrams |

| Children | Shirley Marie Turner |

Len De Caux (aka Leonard De Caux) (1899–1991) was a 20th-Century labor activist in the United States of America who served as publicity director for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and worked to stop passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947.[1][2][3]

Background

Leonard Howard DeCaux was born in Westport, New Zealand, on October 14, 1899. His father was an Anglican vicar.[1][3]

In the United Kingdom, he studied at Harrow School and then Oxford University in Classics.[1]

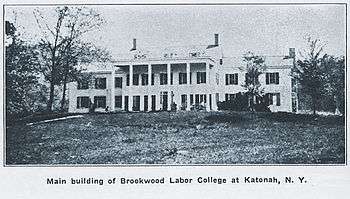

In 1921, he emigrated to the United States, where he worked as a laborer and merchant seaman; he joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). From 1922 to 1924 he attended the Brookwood Labor College.[1][3]

Career

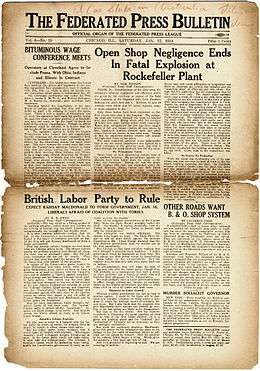

Federated Press 1925–1935

In 1925, Carl Haessler of the Federated Press, a labor news service, hired De Caux and sent him to the United Kingdom and Germany as a foreign correspondent. During this period, De Caux joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (founded in 1920). In 1926, he came back to the States as assistant editor on the United Mine Workers (UMW) Illinois Miner under Oscar Ameringer. In late 1926, he went to Cleveland late as assistant editor of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers Journal. In 1933, he rejoined the Federated Press as Washington correspondent.[1][3]

CIO 1935–1947

In 1935, De Caux became publicity director of the newly formed CIO under founder John L. Lewis. In 1937, he also became editor of the CIO News.[1][3]

Labor for Victory 1947

De Caux received mention from Time magazine in April 1942. The AFL and the CIO had agreed to a joint radio production, called Labor for Victory. Negotiations started in the summer of 1941. By April 1942, NBC had agreed to run the weekly segment as a "public service." The AFL and CIO presidents William Green and Philip Murray had agreed to let their press chiefs, Philip Pearl and De Caux, alternate weeks between them to narrate. The show ran on NBC radio on Saturdays 10:15–10:30 PM, starting on April 25, 1942. Time wrote, "De Caux and Pearl hope to make the Labor for Victory program popular enough for an indefinite run, using labor news, name speakers and interviews with workmen. Labor partisanship, they promise, is out."[4][5]

Writers for Labor for Victory included: Peter Lyon, a progressive journalist; Millard Lampell (born Allan Sloane), later an American movie and television screenwriter; and Morton Wishengrad, who worked for the AFL.[6][7]

For entertainment on CIO episodes, De Caux asked Woody Guthrie to contribute to the show. "Personally, I would like to see a phonograph record made of your "Girl in the Red, White, and Blue."[8] However, the title appears in at least one collection of Guthrie records.[9] Guthrie consented and performed solo two or three times on this among several other WWII radio shows, including Answering You, Labor for Victory, Jazz in America, and We the People.[10][11][12] The Almanac Singers (of which Guthrie and Lampell were co-founders) did appear (as they did on the U.S. Navy's (or U.S. Treasury's) The Treasury Hour and CBS Radio's We the People, later a television show).[13] (Also, Marc Blitzstein's papers show that he made unclear contributions to four CIO episodes (dated June 20, June 27, August 1, August 15, 1948) of Labor for Victory.[14])

While Labor for Victory was a milestone in theory as a national platform, in practice it proved less so. Only 35 of 104 NBC affiliates carried the show.[5][15][16]

NBC's announced the show represented "twelve million organized men and women, united in the high resolve to rid the world of Fascism in 1942." Speakers included Donald E. Montgomery, then "consumer's counselor" at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. [17][18][19]

Taft-Hartley 1947

In the aftermath of World War II, both the press and business interests expressed hostility toward organized labor (unions). Moreover, business interests funded their lobbyists better. For example, in 1946 and 1947, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) had a budget of $3.6 million (including $1.9 million for advertising), while the CIO publicity department had $200 thousand, while the CIO's research and education department had another $200 thousand and AFL counterparts had even smaller budgets. Thus, the CIO and AFL had combined budgets of under half a million dollars annually, while their largest counterpart NAM had an annual budget seven times larger – amidst major lobbying efforts that included the landmark 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. De Caux himself, for his part, was hand-tied by suspicion of his communist ties.[2]

Nevertheless, the CIO's second president Philip Murray had De Caux work with the CIO's legislation and research departments on key messaging to "John Q. Public." The CIO used monies raised largely through the CIO Political Action Committee (CIO-PAC), itself an object of concern to politicians and business interests. Efforts by De Caus included: leaflets (e.g., "Your Union is in Danger!"), pamphlets (e.g., "Defend Your Union"), analyses of Congressional agenda, observance of the CIO-PAC's Defend Labor Month, and calls to union members for political action.[2]

In response:

De Caux developed a thorough plan for publicizing labor’s objections to the Taft and Hartley bills to the general public. In it, De Caux detailed plans for all of the activities expected of the grassroots, member-focused programming that the CIO Executive Board had endorsed: the continued printing of CIO pamphlets and advertisement mats for placement (and payment) by international and local unions, special editions of the CIO News, and the use of existing CIO-sponsored radio programs to publicize Defend Labor Month activities.[2]

De Caux's public relations campaign comprised: pre-recorded and live radio address by CIO president Murray, radio spots, placement of CIO officials on existing radio programs, paid newspaper advertisements, anti-Taft-Hartley press kits, and campaigns that targeted different American groups (African-American, non-English speakers, farmers, etc.).[2]

In late 1947, second president Philip Murray asked De Caux to resign as the CIO began to rid itself of perceived communists and fellow travelers in its ranks (e.g., Lee Pressman in February 1948).[1]

Wallace support 1948

In 1948, De Caux was active in the Progressive Party presidential campaign of Henry A. Wallace. He served as publicity director for the Labor Division.[1]

Later years

From 1952 to 1953, De Caux served as managing editor of March of Labor magazine; he left due to financial shortages of the publisher.[1]

During the McCarthy Era, he testified before the U.S. Congress regarding his involvement with the Institute of Pacific Relations.[1] In 1954, former Ware Group member Hope Hale Davis identified De Caux as a communist to the FBI (along with his wife, her own husband Robert Gorham Davis, Harold Ware, Charles Kramer and his wife Mildred, John Abt and wife Jessica Smith Ware Abt and sister Marion Abt Bachrach, Nathan Witt, Lee Pressman, Victor Perlo, Abraham George Silverman, Henry Collins, Donald Hiss, Alger Hiss, J. Peters, and Jacob Golos.[20] She cited husband and wife De Caux as "an extremely well concealed' Party members.[21]

As a result of branding as a communist, De Caux found himself unable to work for labor causes. From 1955, he retrained and worked as a linotype operator until his retirement in 1965.[1]

Personal and death

In 1928, De Caux married Caroline Abrams. Abrams was born in Bessarabia, then in Russia. Arriving as a child in the States, she worked through her teens and joined the Amalgamated Clothing Workers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and and the Young Peoples Socialist League. She supported Socialist candidates and was against American entry into World War I.

Abrams and De Caux met at Brookwood, by which time she was already experienced as a labor activist. In the 1930s and 1940s, she served as a labor research director but resigned in the early 1940s due to a split between former CIO president Lewis and new president Murray. Like her husband, she worked to elect Wallace as president. She died in 1959. The couple had one child, Shirley Marie Turner.[1]

De Caux died on May 24, 1991.[22][23]

Legacy

De Caux's most important work was to defend organized labor against the Taft-Hartley bill.

Burstein has assessed De Caux as "innovative":

Len De Caux, the CIO’s publicity director, was among the most innovative in pushing for the implementation of differentiated messaging for a variety of important postwar groups. To ensure that servicemen supported organized labor upon their return home, De Caux began producing special editions of the CIO member newspaper, the CIO News, and shipping them to military personnel abroad, free of charge, during the war. By 1946, Fortune Magazine reported that veterans had a more favorable attitude toward organized labor than the general population.[2]

In May 1977, De Caux gave his papers to the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs at Wayne State University. The De Caux's personal correspondence appears separately in the "Brookwood Labor College Collection." Len De Caux's correspondence appears variously in the "Henry Kraus Collection," the "Mary Heaton Vorse Collection," and the "Mary van Kleek Collection." The Walter Reuther Archives at Wayne State University also have an oral history by Len DeCaux dated March 1961.[1]

Works

- Oral History Interviews with Len De Caux (1961)[24]

- Tell It Like It Was, and Is : A Labor Day Address (1969)[25]

- Labor Radical: From the Wobblies to CIO, a P ersonal History (1970, 1971)[26]

- The Living Spirit of the Wobblies (1978)[27]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Len and Caroline DeCaux Papers" (PDF). Wayne State University. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burstein, Rachel (3 June 2014). The Fight Over John Q: How Labor Won and Lost the Public in Postwar America, 1947-1959 (Thesis). City University of New York (CUNY). Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Social History of the United States. p. 234. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Radio: Labor Goes on Air". Time magazine. 20 April 1942. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 Hilmes, Michele (2007). NBC: America's Network. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 73. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Christopher H. Sterling, ed. (13 May 2013). Biographical Dictionary of Radio. Routledge. p. 293. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Christopher H. Sterling; Cary O'Dell, eds. (12 April 2010). The Concise Dictionary of America Radio. Routledge. p. 563. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ John S. Partington, ed. (17 September 2016). The Life, Music and Thought of Woody Guthrie: A Critical Appraisal. Routledge. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Woodie Guthrie: American Radical Patriot". WoodieGuthrie.org. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Jackson, Mark (2001). "In Search of Woody Guthrie at the Library of Congress" (PDF). Folklife Center News. 23: 7–9. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ↑ Denisoff, R. Serge (1968). Folk Consciousness: People's Music and American Communism. Simon Fraser University. p. 241. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Robert Santelli; Emily Davidson, eds. (1999). Hard Travelin': The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie. Wesleyan University Press. p. 241. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Kaufman, Will. Woody Guthrie, American Radical. 2011: University of Illinois Press. p. 84. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ↑ Pollack, Howard (31 July 2017). Marc Blitzstein: His Life, His Work, His World. London, New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Fones-Wolf, Elizabeth A. (2006). Waves of Opposition: Labor and the Struggle for Democratic Radio. University of Illinois Press. p. 103. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Godfried, Nathan (1997). WCFL, Chicago's Voice of Labor, 1926-78. University of Illinois Press. p. 210. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Labor for Victory". Pandora. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Labor for Victory". Amazon. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Labor for Victory". SoundCloud. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "FOIA: Hiss, Alger-Whittaker Chambers-NYC-53". Achive.org. 1954. p. 302. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "FOIA: Hiss, Alger-Whittaker Chambers-NYC-53". Achive.org. 1954. p. 309. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Persons born on 14 October 1899 with first names starting with L". SortedByBirthName. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Len DeCaux (1899-1991)". LibraryThing. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ De Caux, Len (March 1961). Oral History Interviews with Len De Caux. Wayne State University. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ De Caux, Len (1969). Tell It Like It Was, and Is : A Labor Day Address. First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ de Caux, Len (1970). Labor Radical: From the Wobblies to CIO, a Personal History. Boston: Beacon Press. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ de Caux, Len (1978). The Living Spirit of the Wobblies. New York: International Publishers. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

External sources

Written

- "Len and Caroline DeCaux Papers" (PDF). Wayne State University. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- WorldCat

- "Series "Labor for Victory": NBC AFL & CIO Production Saturdays 10:15-10:30 pm". Jerry Haendiges Vintage Radio Logs. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

Images

- Getty Images Portrait of labor leader Len De Caux (March 10, 1947)

.svg.png)