Lelang Commandery

| Lelang Commandery | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 樂浪郡 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 乐浪郡 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul |

낙랑군 (S) 락랑군 (N) | ||||||

| Hanja | 樂浪郡 | ||||||

| |||||||

Lelang Commandery was one of the Chinese commanderies which was established after the fall of Wiman Joseon in 108 BC until Goguryeo conquered it in 313.[1] Though disputed by North Korean scholars, Western sources generally describe the Lelang Commandery as existing within the Korean peninsula, and extend the rule of the four commanderies as far south as the Han River (Korea).[2][3] However, South Korean scholars assumed its administrative areas to Pyongan and Hwanghae region.[4]

History

In 108 BC, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty conquered the area under King Ugeo, a grandson of King Wiman. The Emperor set up Lelang, Lintun, Xuantu and Zhenfan, known as the Four Commanderies of Han in the northern Korean peninsula and Liaodong peninsula. The Book of Han records Lelang belonged to Youzhou, located in northwestern Gojoseon consisted of 25 prefectures, 62,812 houses, and the population was 406,748.[5] Its capital was located Nakrang-guyok, P'yŏngyang. (Rakrang 樂浪/락랑 is a district in central P'yŏngyang today.)[6]

After Emperor Wu's death, Zhenfan and Lintun were abolished and Xuantu was moved to Liaodong. Some prefectures of the abolished commanderies were incorporated into Lelang. Lelang after the consolidation is sometimes called "Greater Lelang commandery". Since Lelang became too large, the Defender of the Southern Section (南部都尉) was set up to rule the seven prefectures which formerly belonged to Zhenfan. Before that, the Defender of the Eastern Section (東部都尉) was set up to rule former Lintun's seven prefectures.

Immigrants mainly from Yan and Qi settled in the former Gojoseon lands and brought with them Chinese culture. Among them, the Wang clan, whose ancestor is said to have fled there from Qi in the 2nd century BC, became powerful.

While the Han dynasty was taken over by Wang Mang, Wang Tiao (王調) started a rebellion and tried to secede from China. In 30 AD, the rebellion was stopped by Wang Zun (王遵), whom Emperor Guangwu appointed as governor. Lelang came under the direct control of China once again. However, the shortage of human resources caused by the turmoil resulted in the abolishment of the seven eastern prefectures. The administration was left to the Hui (濊) natives, whose chiefs were conferred as marquises.

At the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, Gongsun Du, appointed as the Governor of Liaodong in 184, extended his semi-independent domain to the Lelang and Xuantu commanderies. His son Gongsun Kang separated the southern half from the Lelang commandery and established the Daifang commandery in 204. As a result, the Lelang commandery reverted to its original size.

In 236, under the order of Emperor Ming of Cao Wei, Sima Yi crushed the Gongsun family and annexed Liaodong, Lelang and Daifang to Wei. Sima Yi did not encourage frontier settlers to continue their livelihoods in the Chinese northeast and instead ordered households who wished to return to coastal and central China to do so, evacuating the region of Chinese settlers. The Jin Shu records the number of households in the Korean commanderies of Lelang and Daifeng as 8,600 households, less than a sixth of the figures given in the Hou Han Shu for Lelang (which included Daifeng). Liaodong would be out of Chinese hands for centuries due to the lack of Chinese presence there as a result of the policies the Wei court adopted for the commanderies after the fall of the Gongsun family. [7]

Lelang was then inherited by the Jin dynasty. Due to bitter civil wars, Jin was unable to control the Korean peninsula at the beginning of the 4th century and was no longer able to dispatch officials to the frontier commanderies, which were maintained by the dwindling local population of remaining Han Chinese residents. The Zizhi Tongjian states that Zhang Tong (張統) of Liaodong, Wang Zun (王遵) of Lelang and over one thousand households decided to break away from Jin and submit to the Xianbei warlord of Former Yan Murong Hui. Murong Hui relocated the remnants of the commandery to the west within Liaodong. Goguryeo annexed the former territory of Lelang in 313. Goguryeo ended China's rule on the Korean peninsula by conquering Lelang in 313. After Lelang's fall, some commandery residents may have fled south to the indigenous Han polities there, bringing with them their culture that spread to the southern part of the Korean peninsula. With the collapse of the commanderies after four centuries of Chinese rule, Goguryeo and the native polities in the south that became Baekje and Silla began to grow and develop rapidly, heavily influenced by the culture of the Four Commanderies of Han.[8]

Goguryeo absorbed much of what was left of Lelang through its infrastructure, economy, local inhabitants, and advanced culture. Unable to govern the region directly and form a new political center immediately, Goguryeo began to consolidate authority by replacing previous government administrators with its own appointed officials, mostly refugees and exiles from China, the most famous being Dong Shou (冬壽) who was entombed at Anak Tomb No. 3, overtly retaining the previous administrative system of Lelang. In 334 Goguryeo established the fortress and city of Pyongyang-song within the center of the former commandery. Towards the end of the 4th century, in order to focus on the growing threat of Baekje and having checked the power of Former Yan in Liaodong, Goguryeo began to actively strengthen and govern the city. In 427 Goguryeo moved its capital to Pyongyang from its former capital of Ji'an as the new political center of the kingdom in order to administer its territories more effectively.[9]

Revisionism

In the North Korean academic community and some parts of the South Korean academic community, the Han dynasty's annexation of the Korean peninsula have been denied. Proponents of this revisionist theory claim that the Lelang Commandery actually existed outside of the Korean peninsula, and place them somewhere in Liaodong Commandery, China instead.[10]

The demonization of Japanese historical and archaeological findings in Korea as imperialist forgeries owes in part to those scholars' discovery of the Lelang Commandery—by which the Han Dynasty administered territory near Pyongyang—and insistence that this Chinese commandery had a major impact on the development of Korean civilization.[11] Until the North Korean challenge, it was universally accepted that Lelang was a commandery established by Emperor Wu of Han after he defeated Gojoseon in 108 BCE.[12] To deal with the Han Dynasty tombs, North Korean scholars have reinterpreted them as the remains of Gojoseon or Goguryeo.[11] For those artifacts that bear undeniable similarities to those found in Han China, they propose that they were introduced through trade and international contact, or were forgeries, and "should not by any means be construed as a basis to deny the Korean characteristics of the artifacts".[13] The North Koreans also say that there were two Lelangs, and that the Han actually administered a Lelang on the Liao River on the Liaodong peninsula, while Pyongyang was an "independent Korean state" of Lelang, which existed between the 2nd century BCE until the 3rd century CE.[14][15] The traditional view of Lelang, according to them, was expanded by Chinese chauvinists and Japanese imperialists.[16]

These hypotheses are "dictatorial" in the academic community of North Korea, which is supported by the amateur historical enthusiasts in South Korea, but this theory is not recognized at all in the academic circles of the United States, China and Japan.[note 1]

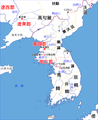

Maps

- Four Commanderies of Han with Jin in 106 BC

Four Commanderies of Han in 3 AD

Four Commanderies of Han in 3 AD

See also

- List of China-related topics

- List of Korea-related topics

- Four Commanderies of Han

- Daifang commandery

- Canghai Commandery

Notes

- ↑

- United States Congress (2016). North Korea: A Country Study. Nova Science Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-1590334430.

- "Han Chinese built four commanderies, or local military units, to rule the peninsula as far south as the Han River, with a core area at Lolang (Nangnang in Korean), near present-day P'yongyang. It is illustrative of the relentlessly different historiography practiced in North Korea and South Korea, as well as both countries' dubious projection backward of Korean nationalism, that North Korean historians denied that the Lolang district was centered in Korea and placed it northwest of the peninsula, possibly near Beijing."

- Connor, Edgar V. (2003). Korea: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Science Publishers. p. 112. ISBN 978-1590334430.

- "They place it northwest of the peninsula, possibly near Beijing, in order to de- emphasize China's influence on ancient Korean history."

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0253000248.

- "Immediately after destroying Wiman Chosŏn, the Han empire established administrative units to rule large territories in the northern Korean peninsula and southern Manchuria."

- Hyung, Hyung Il (2000). Constructing “Korean” Origins. Harvard University Press. p. 129. ISBN 9780674002449.

- "When material evidence from the Han commandery site excavated during the colonial period began to be reinterpreted by Korean nationalist historians as the first full-fledged "foreign" occupation in Korean history, Lelang's location in the heart of the Korean peninsula became particularly irksome because the finds seemed to verify Japanese colonial theories concerning the dependency of Korean civilization on China."

- Hyung, Hyung Il (2000). Constructing “Korean” Origins. Harvard University Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780674002449.

- "At present, the site of Lelang and surrounding ancient Han Chinese remains are situated in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. Although North Korean scholars have continued to excavate Han dynasty tombs in the postwar period, they have interpreted them as manifestations of the Kochoson or the Koguryo kingdom."

- Xu, Stella Yingzi (2007). That glorious ancient history of our nation. University of California, Los Angeles. p. 223. ISBN 9780549440369.

- "Lelang Commandery was crucial to understanding the early history of Korea, which lasted from 108 BCE to 313 CE around the P'yongyang area. However, because of its nature as a Han colony and the exceptional attention paid to it by Japanese colonial scholars for making claims of the innate heteronomy of Koreans, post 1945 Korean scholars intentionally avoided the issue of Lelang."

- Lee, Peter H. (1993). Sourcebook of Korean Civilization. Columbia University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0231079129.

- "But when Emperor Wu conquered Choson, all the small barbarian tribes in the northeastern region were incorporated into the established Han commanderies because of the overwhelming military might of Han China."

- Barnes, Gina (2000). State Formation in Korea. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0700713233.

- "Despite recent suggestions by North Korean scholars that Lelang was not a Chinese commandery, the traditional view will be adhered to here. Lelang was one of four commanderies newly instituted by the Han Dynasty in 108 BC in the former region of Chaoxian. Of these four commanderies, only two (Lelang and Xuantu) survived successive reorganizations; and it seems that even these had their headquarters relocated once or twice."

- Ch'oe, Yŏng-ho (May 1981), "Reinterpreting Traditional History in North Korea", The Journal of Asian Studies, 40 (3): 509, doi:10.2307/2054553.

- "North Korean scholars, however, admit that a small number of items in these tombs resemble those found in the archaeological sites of Han China. These items, they insist, must have been introduced into Korea through trade or other international contacts and "should not by any means be construed as a basis to deny the Korean characteristics of the artifacts" found in the P'yongyang area."

- Jr. Clemens, Walter C. (2016). North Korea and the World: Human Rights, Arms Control, and Strategies for Negotiation. University Press of Kentucky. p. 26. ISBN 978-0813167466.

- "Chinese forces subsequently conquered the eastern half of the peninsula and made lolang, near modern Pyongyang, the chief base for Chinese rule. Chinese sources recall how China used not only military force but also assassination and divide-and-conquer tactics to subdue Chosŏn and divide the territory into four commanderies."

- Seth, Michael J. (2016). A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 978-1442235175.

- "For the next four centuries a northwestern part of the Korean peninsula was directly incorporated in to the Chinese Empire.... The Taedong River basin, the area where the modern city of P'yongyang is located, became the center of the Lelang commandery."

- Seth, Michael J. (2016). A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 978-1442235175.

- "The way of life maintained by the elite at the capital in the P'yongyang area, which is known from the tombs and scattered archaeological remains, evinces a prosperous, refined, and very Chinese culture."

- Seth, Michael J. (2016). A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-1442235175.

- "The Chinese, having conquered Choson, set up four administrative units called commanderies. The Lelang commandery was located along the Ch'ongch'on and Taedong rivers from the coast to the interior highlands. Three other commanderies were organized: Xuantu, Lintun, and Zhenfan. Lintun and originally Xuantu were centered on the east coast of northern Korea. Zhenfan was probably located in the region south of Lelang, although there is some uncertainty about this. After Emperor Wu's death in 87 BCE a retrenchment began under his successor, Emperor Chao (87-74 BCE). In 82 BCE Lintun was merged into Xuantu, and Zhenfan into Lelang. Around 75 BCE Xuantu was relocated most probably in the Tonghua region of Manchuria and parts of old Lintun merged into Lelang. Later a Daifang commandery was created south of Lelang in what was later Hwanghae Province in northern Korea. Lelang was the more populous and prosperous outpost of Chinese civilization."

- Bowman, John Stewart (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0231110044.

- "Han China resumes its effort to subdue Korea, launching two military expeditions that bring much of the peninsula under Chinese control; it sets up four commanderies in conquered Korea."

- Bowman, John Stewart (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0231110044.

- "After a period of decline, Old Choson falls to Wiman, an exile from the Yan state in northern China. Wiman proves to be a strong ruler, but his ambitious program of expansion eventually brings him into conflict with the Han dynasty of China. The Han defeats Wiman Choson and establishes a protectorate over northern Korea in 108 b.c. Resistance to Chinese hegemony, however, is strong, and China reduces the territory under its active control to Nang-nang colony with an administrative center near modern Pyongyang."

- Lee, Kenneth B. (1997). Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix. Praeger. p. 11. ISBN 978-0275958237.

- "Chinese civilization had started to flow into the Korean Peninsula through Nang-nang. This was the only time in Korean history that China could establish its colonies in the central part of Korea, where occupation forces were stationed. The Han Empire not only occupied Korea, but expanded westward to Persia and Afghanistan."

- Buckley, Patricia (2008). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 100. ISBN 978-0547005393.

- "Lelang commandery, with its seat in modern Pyongyang, was the most important of the four."

- Brian, Brian M. (2012). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 361. ISBN 9780195076189.

- "Chinese commanderies at Lelang (modern Pyongyang) functioned as the political and military arm of Chinese dynasties, beginning with Han, as well as the major contact point between the advanced Chinese civilization and the local population."

- Mark E Byington, Project Director of the Early Korea Project (2009). Early Korea 2: The Samhan Period in Korean History. Korea Institute, Harvard University. p. 172. ISBN 978-0979580031.

- "The latter, associated with Han China, are important, as their discovery permits us to infer the existence of relations between the Han commanderies and the Samhan societies."

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (1998). Hair: Its Power and Meaning in Asian Cultures. State University of New York Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0791437421.

- "These tombs are associated with the Lelang commandery, which was established by the Han dynasty of China, successor to the Qin. Han generals conquered the armies of Wiman's grandson Ugo and established control over the northern part of the Korean peninsula."

- Preucel, Robert W. (2010). Contemporary Archaeology in Theory: The New Pragmatism. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-4051-5832-9.

- "The Wei Ji (compiled 233–97) places the Yemaek in the Korean peninsula at the time of the Han commanderies in the first century BC, giving them a specifically Korean identity at least by that time."

- Dr. Brian, Fagan (2016). Ancient Civilizations. Routledge. p. 365. ISBN 978-1138181632.

- "In 108 B.C. most of the Korean peninsula was divided into four Han commanderies, the most important of which was Lelang."

- Tuan, Yi-Fu (2008). A Historical Geography of China. Aldine Transaction. p. 84. ISBN 978-0202362007.

- "Northeastwards Emperor Wu's forces conquered northern Korea in 108 b.c. and established four command headquarters there."

- Kang, Jae-eun (2006). The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism. Homa & Seka Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-1931907309.

- "Nangnang commandery centered around Pyeong'yang was established when Emperor Wu of Han China attacked Gojoseon in 108 BC and was under the rule of Wei from 238. Wei is the country that destroyed the Later Han dynasty."

- Armstrong, Charles K. (1995), "Centering the Periphery: Manchurian Exile(s) and the North Korean State", Korean Studies, University of Hawaii Press, 19: 12, doi:10.1353/ks.1995.0017

- "North Korean historiography from the 1970s onward has stressed the unique, even sui generis, nature of Korean civilization going back to Old Chosön, whose capital, Wanggömsöng, is now located in the Liao River basin in Manchuria rather than near Pyongyang. Nangnang, then, was not a Chinese commandery but a Korean kingdom, based in the area of Pyongyang."

- Pratt, Keith (2006). Everlasting Flower: A History of Korea. Reaktion Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-1861892737.

- "108 BC: Han armies invade Wiman Choson; Chinese commanderies are set up across the north of the peninsula"

- Nelson, Sarah Milledge (1993). The Archaeology of Korea. Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780521407830.

- "The Chinese commanderies did not extend to the southern half of the peninsula, stretching perhaps as far south as the Han river at the greatest extent, but they did reach the northeast coast."

- Jones, F. C. (1966). The Far East: A Concise History. Pergamon Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0080116419.

- "He then divided the country into military districts, of which the most important was that of Lolang, or Laklang, with headquarters near the modern Pyongyang. Tomb excavations in this area have produced much evidence of the influence of Han civilization in northern Korea."

- Stark, Miriam T. (2008). Archaeology of Asia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 45. ISBN 978-1405102131.

- "The best known of these commanderies is Lelang, centered on the present city of Pyongyang, now the capital of North Korea."

- Swanström, Niklas (2009). Sino-Japanese Relations: The Need for Conflict Prevention and Management. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1847186201.

- "Under Emperor Wu-ti, Han China extended her influence into Korea, and in 108 B.C., the peninsula became a part of the Chinese Empire, with four dependent provinces under the Chinese charge."

- Meyer, Milton W. (1997). Asia: A Concise History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 118. ISBN 978-0847680634.

- "In southern Manchuria, and northern and central Korea, the Chinese established four commanderies, which were subdivided into prefectures."

- Olsen, Edward (2005). Korea, the Divided Nation. Praeger. p. 13. ISBN 978-0275983079.

- "The Han dynasty created four outposts in Korea to control that portion of its border."

- Clemens Jr, Walter C. (2009). Getting to Yes in Korea. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 978-1594514067.

- "Chinese forces subsequently conquered the eastern half of the peninsula and made Lolang, near modern Pyongyang, the chief center of Chinese rule."

- Hwang, Kyung Moon (2010). A History of Korea: An Episodic Narrativea. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 4. ISBN 978-0230205451.

- "In the corridor between the peninsula and northeast China, the Chinese Han dynasty established four “commanderies” that ruled over parts of the peninsula and Manchuria, much as modern imperial powers governed their colonies."

- Tennant, Charles Roger (1996). A history of Korea. Kegan Paul International. p. 22. ISBN 0-7103-0532-X.

- "Soon after, the Wei fell to the Jin and Koguryŏ grew stronger, until in 313 they finally succeeded in occupying Lelang and bringing to an end the 400 years of China's presence in the peninsula, a period sufficient to ensure that for the next 1,500 it would remain firmly within the sphere of its culture."

- Eckert, Carter J. (1991). Korea Old and New: A History. Ilchokak Publishers. p. 13. ISBN 978-0962771309.

- "The territorial extent of the Four Chinese Commanderies seems to have been limited to the area north of the Han River."

- Eckert, Carter J. (1991). Korea Old and New: A History. Ilchokak Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 978-0962771309.

- "As its administrative center, the Chinese built what was inessence a Chinese city where the governor, officials, merchants, and Chinese colonists lived. Their way of life in general can be surmised from the investigation of remains unearthed at T'osong-ni, the site of the Lelang administrative center near modern P'yongyang. The variety of burial objects found in their wooden and brickwork tombs attests to the lavish life syle of these Chinese officials, merchants, and colonial overloads in Lelang's capital. ... The Chinese administration had considerable impact on the life of the native population and ultimatedly the very fabric of Gojoseon society became eroded."

References

- ↑ Historical Atlas of the Classical World, 500 BC--AD 600. Barnes & Noble Books. 2000. p. 2.25. ISBN 978-0-7607-1973-2.

- ↑ Carter J. Eckert, el., "Korea, Old and New: History", 1990, pp. 13

- ↑ http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/Korea.html

- ↑ Yi Pyong-do, 《The studies of the Korean history》 Part 2, Researchs of problems of the Han commanderies, PYbook, 1976, 148 p

- ↑ 前漢書卷二十八地理志第八 "樂浪郡,武帝元封三年開。莽曰樂鮮。屬幽州。戶六萬二千八百一十二,口四十萬六千七百四十八。有雲鄣。縣二十五:朝鮮,讑邯,浿水,水西至增地入海。" Wikisource: the Book of Han, volume 28-2

- ↑ ROBERT WILLOUGHBY (2008). BRADT TRAVEL GUIDE NORTH KOREA, THE. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 1-84162-219-2. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ Gardiner, K.H.J. "The Kung-sun Warlords of Liao-tung (189-238)". Papers on Far Eastern History 5 (Canberra, March 1972), p. 173

- ↑ Kwon, O-Jung. "The History of Lelang Commandery". The Han Commanderies in Early Korean History (Cambridge: Harvard University, 2013), p.96-98

- ↑ Yeo, Hokyu. "The Fall of the Lelang and Daifang Commanderies". The Han Commanderies in Early Korean History (Cambridge: Harvard University, 2013), p. 191-216

- ↑

- “매국사학의 몸통들아, 공개토론장으로 나와라!”. ngonews. 2015-12-24. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19.

- 요서 vs 평양… 한무제가 세운 낙랑군 위치 놓고 열띤 토론. Segye Ilbo. 2016-08-21. Archived from the original on 2017-04-13.

- “갈석산 동쪽 요서도 고조선 땅” vs “고고학 증거와 불일치”. The Dong-a Ilbo. 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- 1 2 Pai, Hyung Il (2000), Constructing "Korean" Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology, Historiography, and Racial Myth in Korean State Formation Theories, Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 127–129

- ↑ Ch'oe, Yŏng-ho (1980), "An Outline History of Korean Historiography", Korean Studies, 4: 23–25, doi:10.1353/ks.1980.0003

- ↑ Ch'oe, Yŏng-ho (1980), "An Outline History of Korean Historiography", Korean Studies, 4: 509, doi:10.1353/ks.1980.0003

- ↑ Ch'oe, Yŏng-ho (1980), "An Outline History of Korean Historiography", Korean Studies, 4: 23–25, doi:10.1353/ks.1980.0003

- ↑ Armstrong, Charles K. (1995), "Centering the Periphery: Manchurian Exile(s) and the North Korean State", Korean Studies, University of Hawaii Press, 19: 11–12, doi:10.1353/ks.1995.0017

- ↑ Ch'oe, Yŏng-ho (1980), "An Outline History of Korean Historiography", Korean Studies, 4: 23–25, doi:10.1353/ks.1980.0003