Leipzig-class cruiser

Nürnberg before the outbreak of war | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Königsberg-class |

| Succeeded by: | M-class cruiser |

| Built: | 1928–1934 |

| In commission: | 1931–1959 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Retired: | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 8,100 to 9,040 metric tons (7,970 to 8,900 long tons; 8,930 to 9,960 short tons) |

| Length: | 177 to 181.3 m (581 to 595 ft) |

| Beam: | 16.3 m (53 ft) |

| Draft: | 5.69 to 5.74 m (18.7 to 18.8 ft) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) |

| Range: | 3,900 nautical miles (7,200 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 2 × Arado 196 floatplanes |

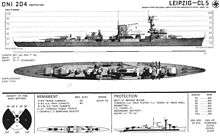

The Leipzig class was a class of two light cruisers of the German Reichsmarine and later Kriegsmarine; the class comprised Leipzig, the lead ship, and Nürnberg, which was built to a slightly modified design. The ships were improvements over the preceding Königsberg-class cruisers, being slightly larger, with a more efficient arrangement of the main battery and improved armor protection. Leipzig was built between 1928 and 1931, and Nürnberg followed between 1934 and 1935.

Both ships participated in the non-intervention patrols during the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and 1937. After the outbreak of World War II, they were used in a variety of roles, including as minelayers and escort vessels. On 13 December 1939, both ships were torpedoed by the British submarine HMS Salmon. They were thereafter used in secondary roles, primarily as training ships, for most of the rest of the war. Leipzig provided some gunfire support to German Army troops fighting on the Eastern Front.

Both ships survived the war, though Leipzig was in very poor condition following an accidental collision with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen late in the war. Leipzig was therefore used as a barracks ship before being scuttled in 1946. Nürnberg, however, emerged from the war largely unscathed, and as a result, was seized by the Soviet Navy as war reparations, and commissioned into the Soviet fleet as Admiral Makarov; she continued in Soviet service until the late 1950s, and was broken up for scrap by 1960.

Design

General characteristics

The two ships of the Leipzig class were not identical, prompting some naval historians to classify them as separate designs, rather than as a ship class.[1] Of the two, Nürnberg was larger. Leipzig was 165.8 meters (544 ft) long at the waterline and 177 m (581 ft) long overall. She had a beam of 16.3 m (53 ft) and a maximum draft of 5.69 m (18.7 ft) forward. She displaced 6,820 metric tons (6,710 long tons; 7,520 short tons) as designed and 8,100 metric tons (8,000 long tons; 8,900 short tons) at full combat load. Nürnberg was slightly longer, at 170 m (560 ft) at the waterline and 181.3 m (595 ft) overall. Her beam was identical to Leipzig, but her draft was slightly greater, at 5.74 m (18.8 ft) forward. She displaced 8,060 metric tons (7,930 long tons; 8,880 short tons) as designed and 9,040 metric tons (8,900 long tons; 9,960 short tons) at full combat load.[2]

The ships' hulls were divided into fourteen watertight compartments and had double bottoms that ran for 83 percent of the length of their keels. Both vessels had side bulges and bulbous bows. They were constructed with longitudinal steel frames, and were more than 90 percent welded in order to save weight. Nürnberg had a large, blocky forward superstructure, while Leipzig's superstructure resembled that of the preceding Königsberg class. Nürnberg also had a large searchlight platform fitted on the funnel, while Leipzig did not.[1][2]

Leipzig initially had a crew of 26 officers and 508 enlisted men. Later in her career, the crew grew to 30 officers and 628 sailors and then again to 24 officers and 826 sailors. She could also accommodate an admiral's staff of 6 officers and 20 enlisted men when she was serving as a flagship. Nürnberg's crew started as 25 officers and 648 ratings, and over the course of her career swelled to 26 officers and 870 enlisted men. The ships carried two picket boats, two barges, two launches, and two cutters.[2]

Both ships carried one aircraft catapult for a pair of Heinkel He 60 biplane reconnaissance float planes. They were equipped with a crane to retrieve the aircraft after landing. The He 60s were later replaced by the monoplane Arado Ar 196 by 1939.[3] Leipzig's catapult was located between the funnel and the forward superstructure, while Nürnberg's was placed aft of the funnel.[4]

Machinery and handling

The ships' propulsion system consisted of two steam turbines manufactured by the Deutsche Werke and Germaniawerft shipyards, along with four 7-cylinder double-acting two-stroke diesel engines built by MAN.[1] Steam for the turbines was provided by six Marine-type double-ended oil-fired boilers. The engines were rated at 60,000 shaft horsepower (45,000 kW) for the turbines plus 12,400 shp (9,200 kW) for the central diesel engines. The ship's propulsion system provided a top speed of 32 kn (59 km/h; 37 mph) and a range of approximately 3,900 nautical miles (7,200 km; 4,500 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) using only the diesel engines. With only the turbines in operation, the ships could steam for 2,800 nmi (5,200 km; 3,200 mi) at a speed of 16.5 kn (30.6 km/h; 19.0 mph).[2]

The ships had extensive electrical generator systems. Leipzig had three power plants that each had a 180 kilowatt turbo-generator and a 180 kW diesel generator; this gave the ship a combined output of 1,080 kW at 220 volts. Nürnberg had four generators which comprised two 300 kW turbo-generators and two 350 kW diesel generators, for a total output of 1,300 kW, also at 220 volts.[2]

Steering was controlled by a single balanced rudder, which gave the ships excellent maneuverability. The rudder was augmented with special steering system on the engine transmissions; they had gears that could drive half of the engines astern and half forward allowed the screws to assist in turning the ship at sharper angles. The ships tended toward lee helm in general conditions, but in heavy wind, they suffered from weather helm. Both vessels also suffered from severe leeway at low speeds, and the effect was especially pronounced for Nürnberg, owing to her larger superstructure.[2]

Armament and armor

Leipzig and Nürnberg were armed with nine 15 cm SK C/25 guns mounted in three triple gun turrets. One was located forward, and two were placed in a superfiring pair aft, all on the centerline. They were supplied with between 1,080 and 1,500 rounds of ammunition, for between 120 and 166 shells per gun. As built, Leipzig was also equipped with two 8.8 cm SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns in single mounts; they had 800 rounds of ammunition. Nürnberg meanwhile was built with eight of these weapons with 3,200 rounds in total. Nürnberg also carried eight 3.7 cm SK C/30 anti-aircraft guns, and several 2 cm anti-aircraft guns, though the number of the latter changed over her career. The two ships also carried four triple torpedo tube mounts located amidships; Leipzig had 50 cm (20 in) weapons while Nürnberg was equipped with 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedoes. They were supplied with twenty-four torpedoes. They were also capable of carrying 120 naval mines.[2]

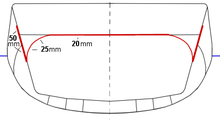

Leipzig used Krupp cemented armor, while Nürnberg received the newly developed Wotan Hart steel. The ships were protected by an armored deck that was 30 mm (1.2 in) thick amidships and an armored belt that was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick. The belt was inclined to a greater degree than in the preceding Königsbergs, to increase the effectiveness of the same thickness of armor plate. The sloping armor that connected the deck with the belt was 25 mm (0.98 in) thick. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides with a 50 mm thick roof. The gun turrets had 80 mm (3.1 in) thick faces, 35 mm (1.4 in) thick sides, and 32 mm (1.3 in) thick roofs. They were mounted on barbettes that were protected with 60 mm (2.4 in) of steel plating.[2]

Modifications

After the outbreak of war, both ships were fitted with a degaussing coil to protect them against magnetic mines.[3][5] Leipzig had her aircraft equipment removed in 1941, along with her after torpedo tubes.[5] In 1942, Nürnberg's aircraft handling equipment and aft torpedo tubes were also removed. Throughout the war, the ships' radar suites were upgraded; in March 1941, Nürnberg was equipped with FuMO 21 radar and in early 1942, a FuMO 25 radar set was installed.[6] The latter was a search radar for surface targets and low-flying aircraft at low range. The FuMO 21 set was replaced by the short-range FuMO 63 Hohentwiel 50-centimeter radar. Nürnberg was also fitted with four Metox radar warning receivers.[7] Leipzig did not receive her FuMO 24/25 radar set until 1943; this was to be the last modification for Leipzig.[8]

Leipzig had her anti-aircraft armament modernized to bring her closer to the standard of weaponry fitted to her sister. After 1934, two additional 8.8 cm guns were added, with another pair later. Starting in 1941, eight 3.7 cm guns were installed, along with fourteen 2 cm guns. After 1944, she only carried eight of the 2 cm guns.[2] Nürnberg's anti-aircraft battery was improved over the course of World War II. In late 1942, a pair of Army-variant 2 cm Flakvierling quadruple mounts were installed, one on the navigating bridge and the other on top of the aft superfiring turret. In May 1944, the navy proposed installing several Bofors 40 mm guns, but most of these weapons were diverted to other uses, and only two guns were installed. One was mounted on the bridge and the other where the catapult had been located.[9] Two Navy-pattern Flakvierlings were added; one replaced the Army model atop the aft superfiring turret, and the other was placed in front of the anti-aircraft fire director. The Army-pattern Flakvierlings were moved to the main deck. In December 1944, another revised anti-aircraft plan was proposed, this time incorporating the new 3.7 cm FlaK 43 gun, of which there were to be eight, along with two Flakvierlings and ten 2 cm twin mounts. Germany's wartime situation by the end of 1944 prevented these changes from being made, however.[10]

Construction

| Name | Builder[1] | Laid down[1] | Launched[1] | Commissioned[1] | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leipzig | Kriegsmarinewerft, Wilhelmshaven | 28 April 1928 | 10 October 1929 | 8 October 1931 | Scuttled, 16 December 1946 |

| Nürnberg | Deutsche Werke, Kiel | 4 November 1933 | 6 December 1934 | 2 November 1935 | Transferred to Soviet Navy as Admiral Makarov, 5 November 1945 |

Service history

Leipzig

In the 1930s, Leipzig was used as a training cruiser, as well as to make goodwill visits to foreign ports. She participated in non-intervention patrols during the Spanish Civil War. In the first year of World War II, she performed escort duties for warships in the Baltic and North seas.[11][12] Leipzig was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS Salmon on 13 December 1939 while on one of these operations. The cruiser was badly damaged, and the necessary repairs took almost a year to complete. She thereafter resumed her duties as a training ship.[13] She provided gunfire support to the advancing Wehrmacht troops as they invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.[14]

In a heavy fog in October 1944, Leipzig collided with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen; the damage was so severe that the navy decided complete repairs were unfeasible. Instead, they repaired Leipzig enough to keep her afloat, and in that state, provided gunfire support to the defenders of Gotenhafen against the advancing Red Army in March 1945. As the Germans continued to retreat in the east, Leipzig was then used to transport a group of fleeing German civilians. She reached Denmark by late April. After the end of the war, Leipzig was used as a barracks ship for minesweeping forces and was scuttled in July 1946.[15]

Nürnberg

Following her commissioning, Nürnberg participated in the non-intervention patrols during the Spanish Civil War; she completed her patrols without major incident and returned to Germany in mid-1937. After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, she was used to lay defensive minefields off the German coast in the North Sea.[16] She was thereafter used to escort offensive mine-layers in the North Sea until she was torpedoed by the British submarine Salmon on 13 December 1939.[17] After repairs were completed in early 1940, Nürnberg returned to active duty as a training ship in the Baltic Sea. She performed this role for most of the rest of the war, apart from a short deployment to Norway from November 1942 to April 1943. In January 1945, she was assigned to mine-laying duties in the Skaggerak, but severe shortages of fuel permitted only one such operation.[18]

After the end of the war, Nürnberg was seized by the Royal Navy and ultimately awarded to the Soviet Union as war reparations.[19] In December 1945, a Soviet crew took over the ship, and the following month took her to Tallinn, where she was renamed Admiral Makarov. She served in the Soviet Navy, first in the 8th Fleet, then as a training cruiser based in Kronstadt. Her ultimate fate is unclear, but by 1960, she had been broken up for scrap. Nürnberg was the second-largest warship of the Kriegsmarine to survive the war intact, after the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, and she was the only vessel to see service after the war, albeit in a foreign navy.[20]

Footnotes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leipzig class cruiser. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 231

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gröner, p. 122

- 1 2 Whitley, No. 1, p. 235

- ↑ Gröner, pp. 122–123

- 1 2 Williamson, p. 35

- ↑ Williamson, p. 40

- ↑ Whitley, p. 236

- ↑ Williamson, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Whitley, No. 1, pp. 236–238

- ↑ Whitley, p. 238

- ↑ Williamson, p. 36

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 9

- ↑ Williamson, p. 37

- ↑ Williamson, p. 38

- ↑ Williamson, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Whitley, No. 2, p. 250

- ↑ Rohwer, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Whitley, No. 2, pp. 252–254

- ↑ Whitley, No. 2, p. 254

- ↑ Whitley, p. 255

References

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219138.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Whitley, M. J. (1983). "Lesser Known Warships of the Kriegsmarine No. 1: The Light Cruiser Nürnberg". Warship. London, UK: Conway Maritime Press. VI (23): 234–238.

- Whitley, M. J. (1983). "Lesser Known Warships of the Kriegsmarine No. 2: The Light Cruiser Nürnberg". Warship. London, UK: Conway Maritime Press. VI (24): 250–255.

- Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Light Cruisers 1939–1945. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-503-1.