Cramp

| Cramp | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | R25.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 729.82 |

| DiseasesDB | 3151 |

| MedlinePlus | 003193 |

| Patient UK | Cramp |

| MeSH | D009120 |

A cramp is a sudden, involuntary muscle contraction or over-shortening; while generally temporary and non-damaging, they can cause significant pain, and a paralysis-like immobility of the affected muscle. Onset is usually sudden, and it resolves on its own over a period of several seconds, minutes or hours. Cramps may occur in a skeletal muscle or smooth muscle. Skeletal muscle cramps may be caused by muscle fatigue or a lack of electrolytes such as low sodium, low potassium or low magnesium. Cramps of smooth muscle may be due to menstruation or gastroenteritis.

Pathophysiology

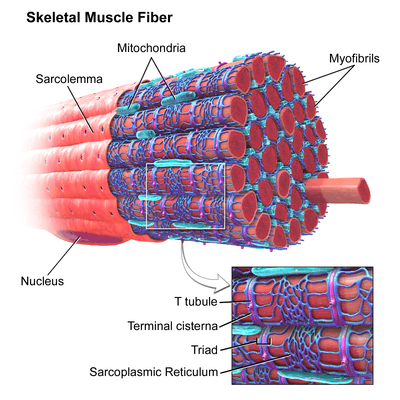

Muscle contraction begins with the brain setting off action potentials, which are waves in the electrical charges that extend along neurons. The waves travel to a group of cells in a muscle, letting calcium ions out from the cells' sarcoplasmic reticula (SR), which are storage areas for calcium. The released calcium lets myofibrils contract under the power of energy-carrying adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules. Meanwhile, the calcium is quickly pumped back into the SR by fast calcium pumps. Each muscle cell contracts fully; stronger contraction of the whole muscle requires more action potentials on more groups of cells in the muscle. When the action potentials stop, the calcium stops flowing from the SR and the muscle relaxes. The fast calcium pumps are powered by the sodium gradient, or the pent-up sodium ions that rush out from the SR. The sodium gradient is maintained by the sodium-potassium pump. A lack of sodium would prevent the sodium gradient from being strong enough to power the calcium pumps; the calcium ions would remain in the myofibrils, forcing the muscle to stay contracted and causing a cramp. The cramp eventually eases as slow calcium pumps, powered by ATP instead of the sodium gradient, push the calcium back into storage.

Electrolyte disturbance, particularly hypokalemia and hypocalcaemia, may cause cramping and muscle tetany. This disturbance can also be caused by the body sweating out large amounts of interstitial fluid, which is mostly water and salt (sodium chloride). As muscle cells contain more osmotically-active particles, the loss of osmotically-active sodium particles from muscle cells disturbs the osmotic balance and therefore shrinks muscle cells. This causes the calcium pump between the muscle sarcoplasm and sarcoplasmic reticulum to "short circuit"; the calcium ions remain bound to the troponin, continuing muscle contraction.

Cramps can occur when muscles are unable to relax properly due to myosin fibers not fully detaching from actin filaments. In skeletal muscle, ATP levels must be large enough to bind to the myosin heads for them to attach or detach from the actin and allow contraction or relaxation; the absence of enough levels of ATP means that the myosin heads remains attached to actin. The muscle must be allowed to recover (resynthesize ATP), before the myosin fibres can detach and allow the muscle to relax. Skeletal muscles work as antagonistic pairs. Contracting one skeletal muscle requires the relaxation of the opposing muscle in the pair. An attempt to force a muscle cramped by low ATP to extend (by contracting the opposing muscle) can tear muscle tissue and worsen the pain.

Differential diagnosis

Causes of cramping include[1] hyperflexion, hypoxia, exposure to large changes in temperature, dehydration, or low blood salt. Muscle cramps can also be a symptom or complication of pregnancy; kidney disease; thyroid disease; hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, or hypocalcaemia (as conditions); restless legs syndrome; varicose veins;[2] and multiple sclerosis.[3]

As early as 1965, researchers observed that leg cramps and restless legs syndrome can result from excess insulin, sometimes called hyperinsulinemia.[4]

Skeletal muscle cramps

Under normal circumstances, skeletal muscles can be voluntarily controlled. Skeletal muscles that cramp the most often are the calves, thighs, and arches of the foot, and are sometimes called a "Charley horse" or a "corky". Such cramping is associated with strenuous physical activity and can be intensely painful; however, they can even occur while inactive and relaxed. Around 40% of people who experience skeletal cramps are likely to endure extreme muscle pain, and may be unable to use the entire limb that contains the "locked-up" muscle group. It may take up to seven days for the muscle to return to a pain-free state.

Nocturnal leg cramps

Nocturnal leg cramps are involuntary muscle contractions that occur in the calves, soles of the feet, or other muscles in the body during the night or (less commonly) while resting. The duration of nocturnal leg cramps is variable, with cramps lasting anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes. Muscle soreness may remain after the cramp itself ends. These cramps are more common in older people.[5] They happen quite frequently in teenagers and in some people while exercising at night. The precise cause of these cramps is unclear. Potential contributing factors include dehydration, low levels of certain minerals (magnesium, potassium, calcium, and sodium, although the evidence has been mixed),[6][7][8] and reduced blood flow through muscles attendant in prolonged sitting or lying down. Nocturnal leg cramps (almost exclusively calf cramps) are considered "normal" during the late stages of pregnancy. They can, however, vary in intensity from mild to extremely painful.

A lactic acid buildup around muscles can trigger cramps; however, these happen during anaerobic respiration when a person is exercising or engaging in an activity where the heartbeat speeds up. Medical conditions associated with leg cramps are cardiovascular disease, hemodialysis, cirrhosis, pregnancy, and lumbar canal stenosis. Differential diagnoses include restless legs syndrome, claudication, myositis, peripheral neuropathy. All of these can be differentiated through careful history and physical examination.[8]

Gentle stretching and massage, putting some pressure on the affected leg by walking or standing, or taking a warm bath or shower may help to end the cramp.[9] If the cramp is in the calf muscle, pulling the big toe gently backwards will stretch the muscle and, in some cases, cause almost immediate relief. There is limited evidence supporting the use of magnesium, calcium channel blockers, carisoprodol, and vitamin B12.[8]

Quinine is no longer recommended for treatment of nocturnal leg cramps due to potential fatal hypersensitivity reactions and thrombocytopenia. Arrhythmias, cinchonism, hemolytic uremic syndrome can also occur at higher dosages.[8]

Smooth muscle cramps

Smooth muscle contractions may be symptomatic of endometriosis or other health problems. Menstrual cramps may also occur both before and during a menstrual cycle.

Iatrogenic causes

Various medications may cause nocturnal leg cramps:[8][10]

- Diuretics, especially potassium sparing

- Intravenous (IV) iron sucrose

- Conjugated estrogens

- Teriparatide

- Naproxen

- Raloxifene

- Long acting adrenergic beta-agonists (LABAs)

- Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (HMG-CoA inhibitors or statins)

Besides being painful, a nocturnal leg cramp can cause much distress and anxiety.[11] Statins may sometimes cause myalgia and cramps among other possible side effects. Raloxifene (Evista) is a medication associated with a high incidence of leg cramps. Additional factors, which increase the probability for these side effects, are physical exercise, age, female gender, history of cramps, and hypothyroidism. Up to 80% of athletes using statins suffer significant adverse muscular effects, including cramps;[12] the rate appears to be approximately 10–25% in a typical statin-using population.[13][14] In some cases, adverse effects disappear after switching to a different statin; however, they should not be ignored if they persist, as they can, in rare cases, develop into more serious problems. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation can be helpful to avoid some statin-related adverse effects, but currently there is not enough evidence to prove the effectiveness in avoiding myopathy or myalgia.[15]

Treatment

Stretching, massage and drinking plenty of fluid, such as water, may be helpful in treating simple muscle cramps.[16] With exertional heat cramps due to electrolyte abnormalities (primarily sodium loss and not calcium, magnesium, and potassium), appropriate fluids and sufficient salt improves symptoms.[17]

Medication

Quinine is likely to be effective; however, due to side effects, its use should only be considered if other treatments have failed.[18] Vitamin B complex, naftidrofuryl, lidocaine, and calcium channel blockers may be effective for muscle cramps.[18] Research has also shown that pickle "juice" can be an effective remedy based on its high sodium and electrolyte content.[19] Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) has proven effective in preventing muscle cramps, although data suggests that effectiveness decreases when taken for more than several weeks.

Prevention

Adequate conditioning, stretching, mental preparation, hydration, and electrolyte balance are likely helpful in preventing muscle cramps.[16]

References

- ↑ Muscle Cramps Symptoms, Causes, Treatment – Do all muscle cramps fit into the above categories on MedicineNet. Medicinenet.com. Retrieved on 2011-02-13.

- ↑ Bergin J. The Vein Book, Hardcover text, Editor Bergin J , 2007.

- ↑ Muscle Cramps at WebMD

- ↑ Roberts, HJ (1965). "Spontaneous Leg Cramps and "restless Legs" Due to Diabetogenic Hyperinsulinism: Observations on 131 Patients". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 13: 602–38. PMID 14300967.

- ↑ Night leg cramps - Mayo Clinic

- ↑ Schwellnus MP, Nicol J, Laubscher R, Noakes TD (2004). "Serum electrolyte concentrations and hydration status are not associated with exercise associated muscle cramping (EAMC) in distance runners". Br J Sports Med. 38 (4): 488–492. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2003.007021.

- ↑ Sulzer NU, Schwellnus MP, Noakes TD (2005). "Serum electrolytes in Ironman triathletes with exercise-associated muscle cramping". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 37 (7): 1081–1085. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000169723.79558.cf.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allen RE, Kirby KA (2012). "Nocturnal Leg Cramps". American Family Physician. 86 (4): 350–355.

- ↑ Ray, C. Claiborne (2009-06-09). "Q & A – A Charley Horse in Bed". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ Garrison, Scott R.; Colin R. Dormuth; Richard L. Morrow; Greg A. Carney; Karim M. Khan (2011-12-12). "Nocturnal Leg Cramps and Prescription Use That Precedes Them: A Sequence Symmetry Analysis". Arch Intern Med. 172: archinternmed.2011.1029. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1029. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ↑ Weiner, Israel H. "Nocturnal Leg Muscle Cramps". JAMA. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ Sinzinger H, O'Grady J (2004). "Professional athletes suffering from familial hypercholesterolaemia rarely tolerate statin treatment because of muscular problems". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 57 (4): 525–8. PMC 1884475

. PMID 15025753. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02044.x.

. PMID 15025753. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02044.x. - ↑ Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Bégaud B (2005). "Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—the PRIMO study". Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 19 (6): 403–14. PMID 16453090. doi:10.1007/s10557-005-5686-z.

- ↑ Dirks, A. J.; Jones, KM (2006). "Statin-induced apoptosis and skeletal myopathy". Am. J. Physiol., Cell Physiol. 291 (6): C1208–12. PMID 16885396. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00226.2006.

- ↑ Lamperti C, Naini AB, Lucchini V, et al. (2005). "Muscle coenzyme Q10 level in statin-related myopathy". Arch. Neurol. 62 (11): 1709–12. PMID 16286544. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.11.1709.

- 1 2 Bentley S (June 1996). "Exercise-induced muscle cramp. Proposed mechanisms and management". Sports Med. 21 (6): 409–20. PMID 8784961. doi:10.2165/00007256-199621060-00003.

- ↑ Bergeron MF (2003). "Heat cramps: fluid and electrolyte challenges during tennis in the heat". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 6 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1016/S1440-2440(03)80005-1.

- 1 2 Katzberg HD, Khan AH, So YT (2010). "Assessment: Symptomatic treatment for muscle cramps (an evidence-based review): Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 74 (8): 691–6. PMID 20177124. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d0ccca.

- ↑ Reynolds, Gretchen (2010-06-09). "Phys Ed: Can Pickle Juice Stop Muscle Cramps?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-11-09.