United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for more than 100 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were known popularly as "greenbacks", a name inherited from the earlier greenbacks, the Demand Notes, that they replaced during 1862. Often termed Legal Tender Notes, they were named United States Notes by the First Legal Tender Act, which authorized them as a form of fiat currency. During the 1860s the so-called second obligation on the reverse of the notes stated:[1]

This Note is Legal Tender for All Debts Public and Private Except Duties On Imports And Interest On The Public Debt; And Is Redeemable In Payment Of All Loans Made To The United States.

They were originally issued directly into circulation by the U.S. Treasury to pay expenses incurred by the Union during the American Civil War. During the next century, the legislation governing these notes was modified many times and numerous versions were issued by the Treasury.

United States Notes that were issued in the large-size format, before 1929, differ dramatically in appearance when compared to modern American currency, but those issued in the small-size format, starting 1929, are very similar to contemporary Federal Reserve Notes with the distinction of having red U.S. Treasury Seals and serial numbers in place of green ones.

Existing United States Notes remain valid currency in the United States; however, as no United States Notes have been issued since January 1971, they are increasingly rare in circulation.

History

Demand Notes

During 1861, the first year of the American Civil War, the expenses incurred by the Union Government much exceeded its limited revenues from taxation, and borrowing was the main vehicle for financing the war. The Act of July 17, 1861[2] authorized United States Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase to raise money via the issuance of $50,000,000 in Treasury Notes payable on demand.[3] These Demand Notes were paid to creditors directly and used to meet the payroll of soldiers in the field. While issued within the legal framework of Treasury Note Debt, the Demand Notes were intended to circulate as currency and were of the same size as banknotes and closely resembled them in appearance.[4] During December 1861, economic conditions deteriorated and a suspension of specie payment caused the government to cease redeeming the Demand Notes as coins.

The Legal Tender Acts

The beginning of 1862 found the Union's expenses increasing, and the government was having trouble funding the escalating war. U.S. Demand Notes—which were used, among other things, to pay Union soldiers—were unredeemable, and the value of the notes began to deteriorate. Congressman and Buffalo banker Elbridge G. Spaulding prepared a bill, based on the Free Banking Law of New York, that eventually became the National Banking Act of 1863.[5]

Recognizing, however, that his proposal would take many months to pass Congress, during early February Spaulding introduced another bill to permit the U.S. Treasury to issue $150 million in notes as legal tender.[6] This caused tremendous controversy in Congress, as hitherto the Constitution had been interpreted as not granting the government the power to issue a paper currency. "The bill before us is a war measure, a measure of necessity, and not of choice," Spaulding argued before the House, adding, "These are extraordinary times, and extraordinary measures must be resorted to in order to save our Government, and preserve our nationality." Spaulding justified the action as a "necessary means of carrying into execution the powers granted in the Constitution 'to raise and support armies', and 'to provide and maintain a navy'".[7] Despite strong opposition, President Abraham Lincoln signed the First Legal Tender Act,[8] enacted February 25, 1862, into law, authorizing the issuance of United States Notes as a legal tender—the paper currency soon to be known as "greenbacks".

Initially, the emission was limited to $150,000,000 total face value between the new Legal Tender Notes and the existing Demand Notes. The Act also intended for the new notes to be used to replace the Demand Notes as soon as practical. The Demand Notes had been issued in denominations of $5, $10, and $20, and these were replaced by United States Notes nearly identical in appearance on the obverse. In addition, notes of entirely new design were introduced in denominations of $50, $100, $500 and $1000. The Demand Notes' printed promise of payment "On Demand" was removed and the statement "This Note is a Legal Tender" was added.

Legal tender status guaranteed that creditors would have to accept the notes despite the fact that they were not backed by gold, bank deposits, or government reserves, and had no interest. However, the First Legal Tender Act did not make the notes an unlimited legal tender as they could not be used by merchants to pay customs duties on imports and could not be used by the government to pay interest on its bonds. The Act did provide that the notes be receivable by the government for short term deposits at 5% interest, and for the purchase of 6% interest 20-year bonds at par. The rationale for these terms was that the Union government would preserve its credit-worthiness by supporting the value of its bonds by paying their interest in gold. Early in the war, customs duties were a large part of government tax revenue and by making these payable in gold, the government would generate the coin necessary to make the interest payments on the bonds. Lastly, by making the bonds available for purchase at par in United States Notes, the value of the latter would be confirmed as well.[3] The limitations of the legal tender status were quite controversial. Thaddeus Stevens, the Chairman of the House of Representatives Committee of Ways and Means, which had authored an earlier version of the Legal Tender Act that would have made United States Notes a legal tender for all debts, denounced the exceptions, calling the new bill "mischievous" because it made United States Notes an intentionally depreciated currency for the masses, while the banks who loaned to the government got "sound money" in gold. This controversy would continue until the removal of the exceptions during 1933.

By the First Legal Tender Act, Congress limited the Treasury's emission of United States Notes to $150,000,000; however, by 1863, the Second Legal Tender Act,[9] enacted July 11, 1862, a Joint Resolution of Congress,[10] and the Third Legal Tender Act,[11] enacted March 3, 1863, had expanded the limit to $450,000,000, the option to exchange the notes for United States bonds at par had been revoked, and notes of $1 and $2 denominations had been introduced as the appearance of fiat currency had driven even silver coinage out of circulation. As a result of this inflation, the greenback began to trade at a substantial discount from gold, which prompted Congress to pass the short-lived Anti-Gold Futures Act of 1864, which was soon repealed after it seemed to accelerate the decrease of greenback value.

The largest amount of greenbacks outstanding at any one time was calculated as $447,300,203.10.[12] The Union's reliance on expanding the circulation of greenbacks eventually ended with the emission of Interest Bearing and Compound Interest Treasury Notes, and the passage of the National Banking Act. However, the end of the war found the greenbacks trading for only about half of their nominal value in gold.[3]

Post Civil War

At the end of the Civil War, some economists, such as Henry Charles Carey, argued for building on the precedent of non-interest-based fiat money and making the greenback system permanent.[13] However, Secretary of the Treasury McCulloch argued that the Legal Tender Acts had been war measures, and that the United States should soon reverse them and return to the gold standard. The House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly to endorse the Secretary's argument.[14] With an eventual return to gold convertibility in mind, the Funding Act of April 12, 1866[15] was passed, authorizing McCulloch to retire $10 million of the Greenbacks within six months and up to $4 million per month thereafter. This he proceeded to do until only $356,000,000 were outstanding during February 1868. By this time, the wartime economic prosperity was ended, the crop harvest was poor, and a financial panic in Great Britain caused a recession and a sharp decrease of prices in the United States.[16] The contraction of the money supply was blamed for the deflationary effects, and caused debtors to agitate successfully for a halt to the notes' retirement.[17]

During the early 1870s, Treasury Secretaries George S. Boutwell and William Adams Richardson maintained that, though Congress had mandated $356,000,000 as the minimum Greenback circulation, the old Civil War statutes still authorized a maximum of $400,000,000[nb 1]—and thus they had at their discretion a "reserve" of $44,000,000. While the Senate Finance Committee under John Sherman disagreed, being of the opinion that the $356,000,000 was a maximum as well as a minimum, no legislation was passed to assert the Committee's opinion. Starting during 1872, Boutwell and Richardson used the "reserve" to counteract seasonal demands for currency, and eventually expanded the circulation of the Greenbacks to $382,000,000 in response to the Panic of 1873.[18]

During June 1874, Congress established a maximum for Greenback circulation of $382,000,000, and during January 1875, approved the Specie Payment Resumption Act, which authorized a reduction of the circulation of Greenbacks towards a revised limit of $300,000,000, and required the government to redeem them for gold, on demand, after 1 January 1879. As a result, the currency strengthened and by April 1876, the notes were on par with silver coins which then began to re-emerge into circulation.[19] On May 31, 1878, the contraction in the circulation was halted at $346,681,016—a level which would be maintained for almost 100 years afterwards.[20] While $346,681,016 was a significant figure at the time, it is now a very small fraction of the total currency in circulation in the United States. The year 1879 found Sherman, now Secretary of the Treasury, in possession of sufficient specie to redeem notes as requested, but as this brought the value of the greenbacks into parity with gold for the first time since the Specie Suspension of December 1861, the public voluntarily accepted the greenbacks as part of the circulating medium.[14]

While the United States Notes had been used as a form of debt issuance during the Civil War, afterwards they were used as a way of moderately influencing the money supply by the federal government—such as through the actions of Boutwell and Richardson. During the Panic of 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt attempted to increase liquidity in the markets by authorizing the Treasury to issue more Greenbacks, but the Aldrich–Vreeland Act provided for the needed flexibility by the National Bank Note supply instead. Eventually, the perceived need for an elastic currency was addressed with the Federal Reserve Notes authorized by the Federal Reserve Act, and attempts to alter the circulating quantity of United States Notes ended.

End of the United States Note

Soon after private ownership of gold was banned during 1933, all of the remaining types of circulating currency, National Bank Notes, silver certificates, Federal Reserve Notes, and United States Notes, were redeemable by individuals only for silver. Eventually, even silver redemption stopped during June 1968, during a time in which all U.S. currency (both coins and paper currency) was changed to fiat currency. For the general public there was then little to distinguish United States Notes from Federal Reserve Notes. As a result, the public circulation of United States Notes, then mainly in the form of $2 and $5 bills, was replaced with $5 Federal Reserve Notes and, eventually, $2 Federal Reserve Notes as well. United States Notes became rare in hand-to-hand commerce and the Treasury converted most of the outstanding balance into $100 bills which spent most of their time in bank vaults. No more United States Notes were distributed into public circulation after January 21, 1971.[21] In September 1994 the Riegle Improvement Act[22] released the Treasury from its long-standing obligation to keep the notes in circulation and finally, during 1996, the Treasury announced that its stock of $100 United States Notes had been destroyed.[23]

Comparison to Federal Reserve Notes

Both United States Notes and Federal Reserve Notes have been legal tender since the gold recall of 1933. Both have been used in circulation as money in the same way. However, the issuing authority for them came from different statutes.[21] United States Notes were created as fiat currency, in that the government has never categorically guaranteed to redeem them for precious metal – even though at times, such as after the specie resumption of 1879, federal officials were authorized to do so if requested. The difference between a United States Note and a Federal Reserve Note is that a United States Note represented a "bill of credit" and was inserted by the Treasury directly into circulation free of interest. Federal Reserve notes are legal tender currency notes. The twelve Federal Reserve Banks issue them into circulation pursuant to the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. A commercial bank belonging to the Federal Reserve System can obtain Federal Reserve notes from the Federal Reserve Bank in its district whenever it wishes. It must pay for them in full, dollar for dollar, by drawing down its account with its district Federal Reserve Bank.

Federal Reserve Banks obtain the notes from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP). It pays the BEP for the cost of producing the notes, which then become liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks, and obligations of the United States Government.

Congress has specified that a Federal Reserve Bank must hold collateral equal in value to the Federal Reserve notes that the Bank receives. This collateral is chiefly gold certificates and United States securities. This provides backing for the note issue. The idea was that if the Congress dissolved the Federal Reserve System, the United States would assume the notes (liabilities). This would meet the requirements of Section 411, but the government would also assume the assets, which would be of equal value. Federal Reserve notes represent a first lien on all the assets of the Federal Reserve Banks, and on the collateral specifically held against them.

Federal Reserve notes are not redeemable in gold, silver or any other commodity, and cannot be exchanged for the collateral held against them. This has been the case since 1933. The notes do not have value for themselves, but for what they will buy. In another sense, because they are legal tender, Federal Reserve notes are "backed" by all the goods and services in the economy.[21]

Characteristics

Like all U.S. currency, United States Notes were produced in a large sized format until 1929, at which time the notes' sizes were reduced to the small-size format of the present day.[nb 2]

The original large-sized Civil War issues were dated 1862 and 1863, and issued in denominations of $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100, $500 and $1000.[25] The United States Notes were dramatically redesigned for the Series of 1869, the so-called Rainbow Notes. The notes were again redesigned for the Series of 1874, 1875 and 1878. The Series of 1878 included, for the first and last time, notes of $5,000 and $10,000 denominations. The final across-the-board redesign of the large-sized notes was the Series of 1880. Individual denominations were redesigned during 1901, 1907, 1917 and 1923.

On small-sized United States Notes, the U.S. Treasury Seal and the serial numbers are printed in red (contrasting with Federal Reserve Notes, where they usually appear in green). By the time the small-size format was adopted, the Federal Reserve System was already existing and there was limited need for United States Notes. They were mainly issued in $2 and $5 denominations in the Series years of 1928, 1953, and 1963. There was a limited issue of $1 notes in the Series of 1928, and an issue of $100 notes in the Series year of 1966, mainly to satisfy legacy legal requirements of maintaining the mandated quantity in circulation. The BEP also printed but did not issue $10 notes in the 1928 Series. An example was displayed at the 1933 Worlds Fair in Chicago.

Section 5119(b)(2) of Title 31, United States Code, was amended by the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 (Public Law 103-325) to read as follows: "The Secretary shall not be required to reissue United States currency notes upon redemption." This does not change the legal tender status of United States Notes nor does it require a recall of those notes already in circulation. This provision means that United States Notes are to be cancelled and destroyed but not reissued. This will eventually result in a decrease in the amount of these notes outstanding.[26]

Large-size United States Notes (1862-1923)

| Value | Year | Fr. | Image | Portrait[nb 3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $1 | 1862–63 | Fr.16c |  |

Salmon P. Chase (Joseph P. Ourdan)[27] |

| $1 | 1869 | Fr.18 |  |

George Washington |

| $1 | 1878 | Fr.27 |  |

George Washington |

| $1 | 1880 | Fr.29 |  |

George Washington |

| $2 | 1862–63 | Fr.41 |  |

Alexander Hamilton |

| $2 | 1869 | Fr.42 |  |

Thomas Jefferson |

| $2 | 1875 | Fr.47 |  |

Thomas Jefferson |

| $2 | 1880 | Fr.52 |  |

Thomas Jefferson |

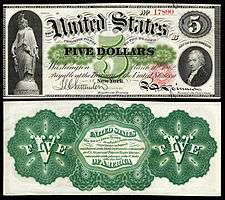

| $5 | 1862–63 | Fr.61a |  |

Freedom (Owen G. Hanks, eng; Thomas Crawford, art)[28] Alexander Hamilton |

| $5 | 1869 | Fr.64 |  |

Andrew Jackson |

| $5 | 1875 | Fr.68 |  |

Andrew Jackson |

| $5 | 1880 | Fr.72 |  |

Andrew Jackson |

| $10 | 1862–63 | Fr.95b |  |

Abraham Lincoln (Frederick Girsch);[29] Eagle; Art |

| $10 | 1869 | Fr.96 |  |

Daniel Webster |

| $10 | 1875 | Fr.98 |  |

Daniel Webster |

| $10 | 1880 | Fr.102 |  |

Daniel Webster |

| $10 | 1901 | Fr.114 |  |

Lewis & Clark |

| $10 | 1923 | Fr.123 |  |

Andrew Jackson |

| $20 | 1862–63 | Fr.126b |  |

Liberty |

| $20 | 1869 | Fr.127 |  |

Alexander Hamilton |

| $20 | 1875 | Fr.128 |  |

Alexander Hamilton |

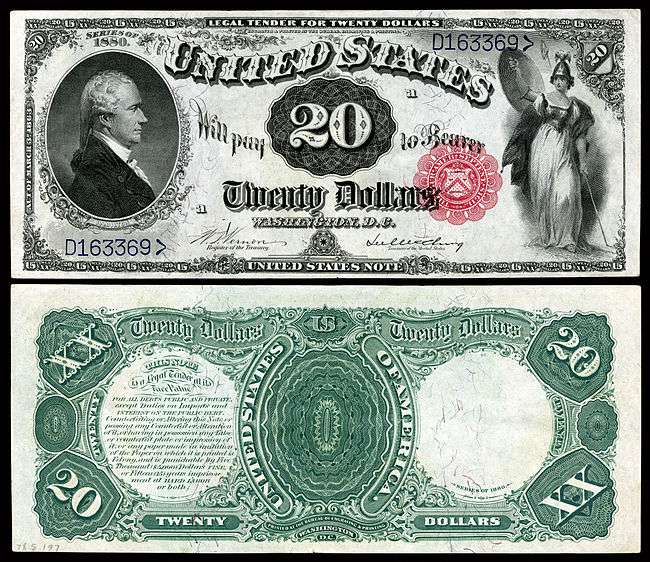

| $20 | 1880 | Fr.145 |  |

Alexander Hamilton |

| $50 | 1862–63 | Fr.148a |  |

Alexander Hamilton (Joseph P. Ourdan)[30] |

| $50 | 1869 | Fr.151 |  |

Henry Clay |

| $50 | 1874 | Fr.152 |  |

Benjamin Franklin |

| $50 | 1880 | Fr.164 |  |

Benjamin Franklin |

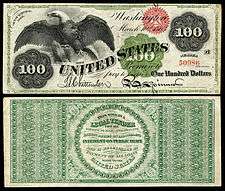

| $100 | 1862–63 | Fr.167 |  |

Vignette spread eagle (Joseph P. Ourdan)[31] |

| $100 | 1869 | Fr.168 |  |

Abraham Lincoln |

| $100 | 1878 | Fr.171 |  |

Abraham Lincoln |

| $100 | 1880 | Fr.181 |  |

Abraham Lincoln |

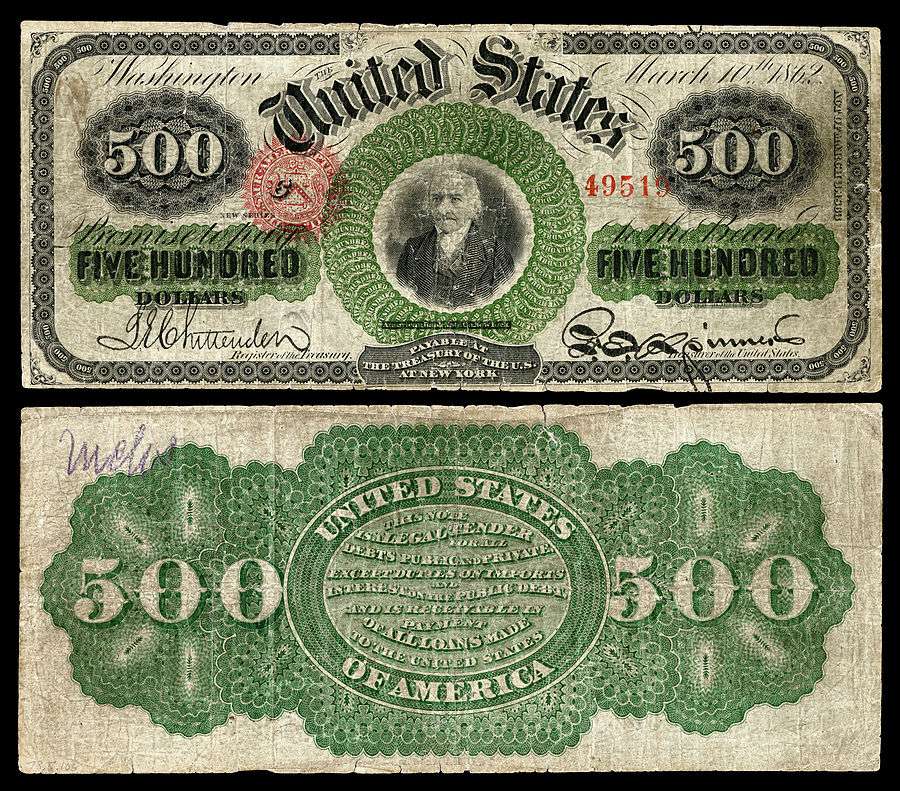

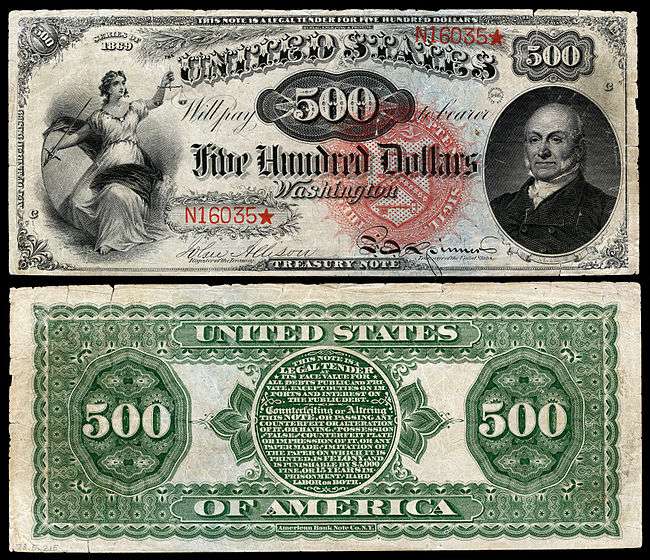

| $500 | 1862–63 | Fr.183c |  |

Albert Gallatin |

| $500 | 1869 | Fr.184 |  |

John Quincy Adams (Charles Burt)[32] |

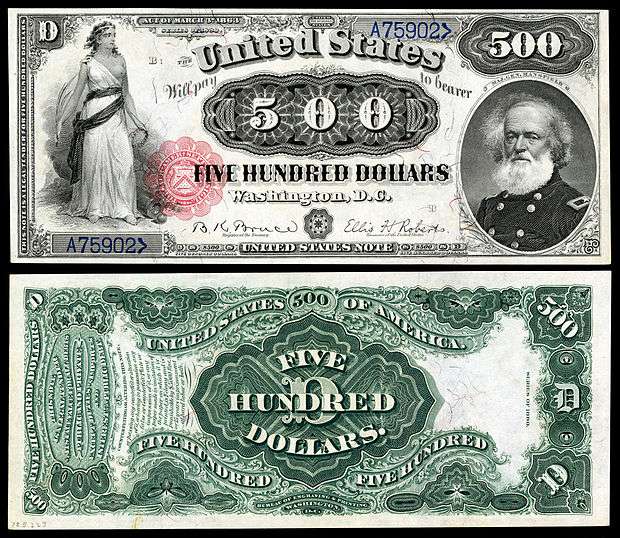

| $500 | 1875 | Fr.185b |  |

Joseph K. Mansfield |

| $500 | 1880 | Fr.185l |  |

Joseph K. Mansfield |

| $1,000 | 1862–63 | Fr.186e |  |

Robert Morris (Charles Schlecht) |

| $1,000 | 1869 | Fr.186f | DeWitt Clinton | |

| $1,000 | 1878 | Fr.187a |  |

DeWitt Clinton |

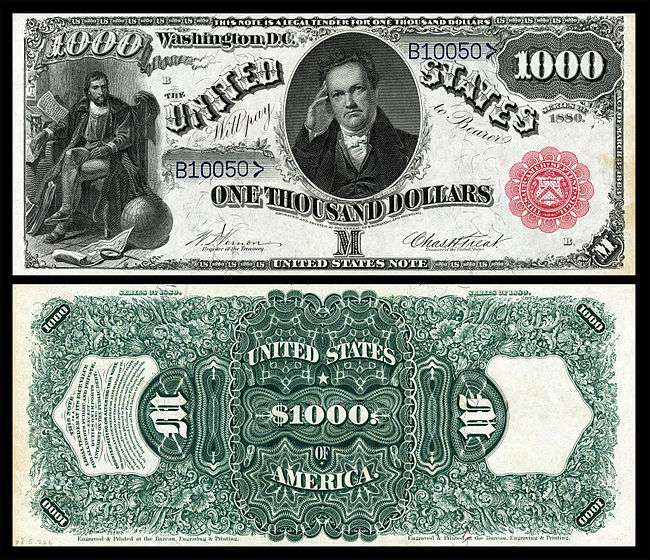

| $1,000 | 1880 | Fr.187k |  |

DeWitt Clinton |

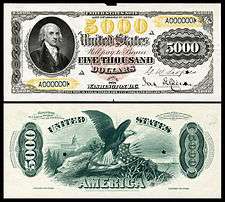

| $5,000 | 1878 | Fr.188 |  |

James Madison |

| $10,000 | 1878 | Fr.189 |  |

Andrew Jackson |

Series 1928 United States Notes

| United States Notes – First small-size issue, Series 1928 (Smithsonian Institution) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main Color | ||||||||

| Obverse/Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||||||||

|

$1 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | George Washington | Stylized "One Dollar" | ||||||

|

$2 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Thomas Jefferson | Monticello | ||||||

|

$5 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Abraham Lincoln | Lincoln Memorial | ||||||

Series 1953 United States Notes

| United States Notes – Small-size issue, Series 1953 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main Color | ||||||||

| Obverse/Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||||||||

|

$2 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Thomas Jefferson | Monticello | ||||||

| $5 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Abraham Lincoln | Lincoln Memorial | |||||||

Series 1963 United States Notes

| United States Notes – Small-size issue, Series 1963 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main Color | ||||||||

| Obverse/Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||||||||

| $2 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Thomas Jefferson | Monticello | |||||||

|

$5 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Abraham Lincoln | Lincoln Memorial | ||||||

Series 1966 United States Notes

| United States Notes – Small-size issue, Series 1966 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main Color | ||||||||

| Obverse/Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||||||||

|

$100 United States Note | 6.140 × 2.610 in (155.956 × 66.294 mm) | Green; Black | Benjamin Franklin | Independence Hall | ||||||

Public debt of the United States

As of December 2012, the U.S. Treasury calculates that $239 million in United States notes are in circulation and, in accordance with debt ceiling legislation, excludes this amount from the statutory debt limit of the United States. The $239 million excludes $25 million in United States Notes issued prior to July 1, 1929, determined pursuant to Act of June 30, 1961, 31 U.S.C. 5119, to have been destroyed or irretrievably lost.[33]

Politics and controversy

The United States Notes were introduced as fiat money rather than the precious metal medium of exchange that the United States had traditionally used. Their introduction was thus contentious.

The United States Congress had enacted the Legal Tender Acts during the U.S. Civil War when southern Democrats were absent from the Congress, and thus their Jacksonian hard money views were underrepresented. After the war, the Supreme Court ruled on the Legal Tender Cases to determine the constitutionality of the use of greenbacks. The 1870 case Hepburn v. Griswold found unconstitutional the use of greenbacks when applied to debts established prior to the First Legal Tender Act as the five Democrats on the Court, Nelson, Grier, Clifford, Field, and Chase, ruled against the Civil War legislation in a 5–3 decision. Secretary Chase had become Chief Justice of the United States and a Democrat, and spearheaded the decision invalidating his own actions during the war. However, Grier retired from the Court, and President Grant appointed two new Republicans, Strong and Bradley, who joined the three sitting Republicans, Swayne, Miller, and Davis, to reverse Hepburn, 5–4, in the 1871 cases Knox v. Lee and Parker v. Davis. During 1884, the Court, controlled 8–1 by Republicans, granted the federal government very broad power to issue Legal Tender paper through the case Juilliard v. Greenman, with only the lone remaining Democrat, Field, dissenting.[18]

The states in the far west stayed loyal to the Union, but also had hard money sympathies. During the specie suspension from 1862 to 1878 western states used the gold dollar as a unit of account whenever possible and accepted greenbacks at a discount wherever they could.[3] The preferred forms of paper money were gold certificates and National Gold Bank Notes, the latter having been created specifically to address the desire for hard money in California.

During the 1870s and 1880s, the Greenback Party existed for the primary purpose of advocating an increased circulation of United States Notes as a way of creating inflation according to the quantity theory of money. However, as the 1870s unfolded, the market price of silver decreased with respect to gold, and inflationists found a new cause in the Free Silver movement. Opposition to the resumption of specie convertibility of the Greenbacks during 1879 was accordingly muted.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ While the three Legal Tender Acts had authorized $450,000,000 of notes, the Second Legal Tender Act, in taking the total from $150,000,000 to $300,000,000 had reserved $50,000,000 of the increase for the purpose of redeeming balances in a temporary deposit program. The Act of June 30, 1864, reiterated this limitation, and as the temporary loan program had ceased to exist, only $400,000,000 of the $450,000,000 ceiling were available.

- ↑ Large size notes represent the earlier types or series of U.S. banknotes. Their "average" dimension is 7.375 x 3.125 inches (187 x 79 mm). Small size notes (described as such due to their size relative to the earlier large size notes) are an "average" 6.125 x 2.625 inches (156 x 67 mm), the size of modern U.S. currency. "Each measurement is +/- 0.08 inches (2mm) to account for margins and cutting".[24]

- ↑ Names in parentheses are either the engravers or artists responsible for the concept and/or initial design.

Notes

- ↑ Friedberg, Arthur L. and Ira S., 2006, Paper Money of the United States, 18th Edition, Clifton, NJ, The Coin & Currency Institute, Inc. ISBN 0-87184-518-0

- ↑ United States Congress. Act of July, 17 1861 Chapter Ⅴ. Washington D.C.: 1861

- 1 2 3 4 Mitchell, Wesley Clair, "A History of the Greenbacks With Special Reference To the Economic Consequences of Their Issue 1862–65", University of Chicago, Chicago, 1903.

- ↑ Chittenden, L.E., Recollections of President Lincoln and His Administration, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1891.

- ↑ D.S. & Heidler, J.T. (2000). Heidler, Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: a political, social, and military history (p. 1168). New York, NY: W.W. Norton

- ↑ McPherson, J.M. (1988). Battle cry of freedom: the Civil War era (p.445). New York, NY: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Spaulding, E.G. (1869). History of the legal tender paper money issued during the great rebellion (p.29). Buffalo, NY: Express Printing.

- ↑ ch. 33, 12 Stat. 345

- ↑ ch. 142, 12 Stat. 532

- ↑ United States Congress. Resolution of January 17, 1863, No. 9. Washington D.C.: 1863

- ↑ ch. 73, 12 Stat. 709

- ↑ Backus, Charles K., "The Contraction of the Currency", The Honest Money League of the Northwest, Chicago, 1878.

- ↑ Carey, Henry Charles (March 1865) The Way to Outdo England Without Fighting Her

- 1 2 "United States Notes", John Joseph Lalor, Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States, Rand McNally & Co, Chicago, 1881.

- ↑ United States Congress. Act of April 12, 1866 Chapter XXXIII. Washington D.C.: 1866

- ↑ Studenski, Paul; Krooss, Hermand Edward (1952). Financial History of the United States, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 1-58798-175-0.

- ↑ The Greenback Question. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- 1 2 Timberlake, Richard H.(1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-80384-5.

- ↑ Bowers, Q. David; David Sundman (2006). 100 GREATEST AMERICAN CURRENCY NOTES, Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 0-7948-2006-9.

- ↑ The National Balance Sheet; It Includes $71,000,000 of Debits Which Might Well Be Dropped" New York Times May 24, 1903, Sunday

- 1 2 3 U.S. Treasury – FAQ: Legal Tender Status

- ↑ Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994, see Sec. 602(f)(4)

- ↑ Hessler, Gene and Chambliss, Carlson (2006). The Comprehensive Catalog of U.S. Paper Money, 7th edition, Port Clinton, Ohio: BNR Press ISBN 0-931960-66-5.

- ↑ Friedberg, p. 7.

- ↑ "Chronology of Large-Size Notes". www.uspapermoney.info. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Historical Legislation - Riegle Improvement Act". www.bep.treas.gov. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ↑ Hessler, 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ Hessler, 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Hessler, 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ Hessler, 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ Hessler, 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Hessler, 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ "Monthly Statement of the Public Debt of the United States" (PDF). United States Treasury Department. 2012-12-31. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

References

- Friedberg, Arthur L.; Friedberg, Ira S. (2013). Paper Money of the United States: A Complete Illustrated Guide With Valuations (20th ed.). Coin & Currency Institute. ISBN 978-0-87184-520-7.

- Hessler, Gene (1993). The Engraver's Line – An Encyclopedia of Paper Money & Postage Stamp Art. BNR Press. ISBN 0-931960-36-3.

- Hessler, Gene (2004). U.S. Essay, Proof and Specimen Notes (2 ed.). BNR Press. ISBN 0-931960-62-2.

Further reading

- Wesley Clair Mitchell, A History of the Greenbacks: With Special Reference to the Economic Consequences of Their Issue, 1862–65. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1903.

- Irwin Unger, The Greenback Era: A Social and Political History of American Finance, 1865–1879. (1965)

- Henry George, "On Greenbacks, Free Silver, and Free Banking," The Standard, December 14, 1889.