Flanking maneuver

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver, or flanking manoeuvre is a movement of an armed force around a flank to achieve an advantageous position over an enemy.[1] Flanking is useful because a force's offensive power is concentrated in its front. Therefore, to circumvent a force's front and attack a flank is to concentrate offense in the area when the enemy is least able to concentrate offense.

Flanking can also occur at the operational and strategic levels of warfare.

Tactical flanking

The flanking maneuver is a basic military tactic, with several variations. Flanking an enemy often refers to staying back and not risking yourself, while at the same time gradually weakening enemy forces. Of course, it may not always work (especially if outnumbered), but for the most part can prove to be effective.

One type is employed in an ambush, where a friendly unit performs a surprise attack from a concealed position. Other units may be hidden to the sides of the ambush site to surround the enemy, but care must be taken in setting up fields of fire to avoid friendly fire.

Another type is used in the attack, where a unit encounters an enemy defensive position. Upon receiving fire from the enemy, the unit commander may decide to order a flank attack. A part of the attacking unit "fixes" the enemy with suppressive fire, preventing them from returning fire, retreating or changing position to meet the flank attack. The flanking force then advances to the enemy flank and attacks them at close range. Coordination to avoid friendly fire is also important in this situation.

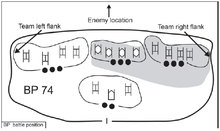

The most effective form of flanking maneuver is the double envelopment, which involves simultaneous flank attacks on both sides of the enemy. A classic example is Hannibal's victory over the Roman armies at the Battle of Cannae. Another example of the double envelopment is Khalid ibn al-Walid's victory over the Persian Empire at the Battle of Walaja.[2]

Despite primarily being associated with land warfare, flanking maneuvers have also been used effectively in naval battles.[3] A famous example of this is the Battle of Salamis, where the combined naval forces of the Greek city-states managed to outflank the Persian navy and won a decisive victory.

Maneuvering

Flanking on land in the pre-modern era was usually achieved with cavalry (and rarely, chariots) due to their speed and maneuverability, while heavily armored infantry was commonly used to fix the enemy, as in the Battle of Pharsalus. Armored vehicles such as tanks replaced cavalry as the main force of flanking maneuvers in the 20th century, as seen in the Battle of France in World War II.

Defense against

The threat of flanking has been existent since the dawn of warfare and the art of being a commander entailed the choice of terrain to allow flanking attacks or prevent them. In addition, proper adjustment and positioning of soldiers is imperative in assuring the protection against flanking.

Terrain

A commander could prevent being flanked by anchoring one or both parts of his line on terrain impassable to his enemies, such as gorges, lakes or mountains, e.g. the Spartans at Thermopylae, Hannibal at the Battle of Lake Trasimene, and the Romans at the Battle of Watling Street. Although not strictly impassable, woods, forests, rivers, broken and marshy ground could also be used to anchor a flank, e.g. Henry V at Agincourt. However, in such instances it was still wise to have skirmishers covering these flanks.

Fortification

In exceptional circumstances, an army may be fortunate enough to be able to anchor a flank with a friendly castle, fortress or walled city. In such circumstances it was not necessary to fix the line to the fortress but to allow a killing space between the fortress and the battle line so that any enemy forces attempting to flank the field forces could be brought under fire from the garrison. Almost as good was if natural strongholds could be incorporated into the battle line, e.g. the Union positions of Culp's Hill, and Cemetery Hill on the right flank, and Big Round Top and Little Round Top on the left flank, at the Battle of Gettysburg. If time and circumstances allowed field fortifications could be created or expanded to protect the flanks, such as the Allied forces did with the hamlet of Papelotte and the farmhouse of Hougoumont on the left and right flanks at the Battle of Waterloo.

Formations

When the terrain favoured neither side it was down to the disposition of forces in the battle line to prevent flanking attacks. For as long as they had a place on the battlefield, it was the role of cavalry to be placed on the flanks of the infantry battle line. With speed and greater tactical flexibility, the cavalry could both make flanking attacks and guard against them. It was the marked superiority of Hannibal’s cavalry at Cannae that allowed him to chase off the Roman cavalry and complete the encirclement of the Roman legions. With equally matched cavalry, commanders have been content to allow inaction, with the cavalry of both sides preventing the other from action.

With no cavalry, inferior cavalry or in armies whose cavalry had gone off on their own (a not uncommon complaint) it was down to the disposition of the infantry to guard against flanking attacks. It was the danger of being flanked by the numerically superior Persians that led Miltiades to lengthen the Athenian line at the Battle of Marathon by decreasing the depth of the centre. The importance of the flank positions led to the practise, which became tradition of placing the best troops on the flanks. So that at the Battle of Platea the Tegeans squabbled with Athenians as to who should have the privilege of holding a flank;[4] both having conceded the honour of the right flank (the critical flank in the hoplite system) to the Spartans. This is the source of the tradition of giving the honour of the right to the most senior regiment present, that persisted into the modern era.

With troops confident and reliable enough to operate in separate dispersed units, the echelon formation may be adopted. This can take different forms with either equally strong "divisions" or a massively reinforced wing or centre supported by smaller formations in step behind it (forming either a staircase like, or arrow like arrangement). In this formation when the foremost unit engages with the enemy the echeloned units remain out of action. The temptation is for the enemy to attack the exposed flanks of this foremost unit, however were this to happen the units immediately echeloned behind the foremost unit would push forward taking the flankers themselves in the flank. If this echeloned unit was to be attacked in turn, the unit behind it, would move forward to again attack the flanks of the would be flankers. In theory a cascade of such engagements could occur all along the line, for as many units as there were in echelon. In practise this almost never happened, most enemy commanders seeing this for what it was, resisting the temptation of the initial easy flanking attack. This prudence was utilised, in the manifestation of the oblique order, in which one wing was massively reinforced, creating a local superiority in numbers that could obliterate that part of the enemy line that it was sent against. The weaker echeloned units being sufficient to fix the greater portion of the enemy troops into inaction. With the battle on the wing won the reinforced flank would turn and roll up the enemy battle line from the flank.

In the Roman chequer board formation, readopted by Renaissance militaries, each of the units in the front line can be thought of as having two lines of units echeloned behind it.

As warfare increased in size and scope and armies got bigger it was no longer possible for armies to hope to have a contiguous battle line. In order to be able to manoeuvre it was necessary to introduce intervals between units and these intervals could be used to flank individual units in the battle line by fast acting units such as cavalry. To guard against this the infantry subunits were trained to be able to rapidly form squares that gave the cavalry no weak flank to attack. During the age of gunpowder, intervals between units could be increased because of the greater reach of the weapons, increasing the possibility of cavalry finding a gap in the line to exploit, and it became the mark of good infantry to be able to form rapidly from line to square and back again.

Operational flanking

On an operational level army commanders may attempt to flank and wrong foot entire enemy armies, rather than just be content with doing so at a tactical battalion or brigade level. The most infamous example of such an attempt is the modified Schlieffen Plan utilized by the Germans during the opening stages of the First World War; this was an attempt to avoid facing the French armies head on, but instead flank them by swinging through neutral Belgium.

Second fronts

Just as at the tactical level a commander will attempt to anchor his flanks, commanders will try to do the same at the operational level. For example, the World War II German Winter Line in Italy anchored by the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic Seas, or for example the trench systems of the Western Front which ran from the North Sea to the Alps. Attacking such positions were and would be expensive in casualties, and more than likely to lead to stalemate. To break such stalemates flanking attacks into areas outside the main zone of contention may be attempted.

If successful, such as at Inchon, such operations can be shattering, breaking into the lightly held rear echelons of an enemy, when its front line forces are committed elsewhere. Even when not entirely successful, for example at Anzio these operations can relieve pressure on troops on the main battle front, by forcing the enemy to divert resources to contain the new front.

These operations may have strategic objectives such as the Invasion of Italy itself, the Gallipoli, and the Normandy landings.

Such a strategy is not new. Hannibal for example attacked Rome by going over the Alps, rather than taking the obvious route. In return Scipio Africanus was able to defeat Hannibal by first undermining his powerbase in Spain before attacking his home city Carthage instead of trying to defeat him in Italy.

Strategic flanking

Flank attacks on the strategic level are seen when a nation or group of nations surround and attack an enemy from two or more directions, such as the Allies surrounding Nazi Germany in World War II. In these cases, the flanked country usually has to fight on two fronts at once, placing it at a disadvantage.

The danger of being strategically flanked has driven the political and diplomatic actions of nations even in peace time. For example, the fear of being strategically flanked by the other in The Great Game 'played' by the British and Russian Empires, led to the expansion of both into China, and the British eastwards into South-East Asia. The British feared that British India would be surrounded by a Persia and Central Asia satellite to Russia in the west and north and a Russian dominated China in the east. Whilst to the Russians a China under British influence would mean that the Russian Empire would be penned in from the south and east. Subsequently the Russians were more successful than the British in gaining territorial concessions in China. However the British were able to counteract this through the cultivation of the emerging Empire of Japan as a counterweight to the Russians, a relationship which culminated in the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

The Cold War version of the Great Game was played on a global scale by the United States and the Soviet Union, each seeking to contain the influence of the other.

Historical examples

See also

- Battleplan (documentary TV series)

- Pincer movement

- Encirclement

Notes

- ↑ Headquarters, department of the Army (2012) Army doctrine reference publication 3-90: Offense and defense. p. 2-11. Retrieved 22 March 2015 from http://armypubs.army.mil/doctrine/DR_pubs/dr_a/pdf/adrp3_90.pdf

- ↑ A.I. Akram (1970). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. National Publishing House. Rawalpindi. ISBN 0-7101-0104-X.

- ↑ Naval maneuver warfare

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, Book Nine, sections 26 to 28