The Carnival of the Animals

The Carnival of the Animals (Le carnaval des animaux) is a humorous musical suite of fourteen movements by the French Romantic composer Camille Saint-Saëns. The work was written for private performance by an ad hoc ensemble of two pianos and other instruments, and lasts around 25 minutes.

History

Following a disastrous concert tour of Germany in 1885–86, Saint-Saëns withdrew to a small Austrian village, where he composed The Carnival of the Animals in February 1886.[1] It is scored for two pianos, two violins, viola, cello, double bass, flute (and piccolo), clarinet (C and B♭), glass harmonica, and xylophone.

From the beginning, Saint-Saëns regarded the work as a piece of fun. On 9 February 1886 he wrote to his publishers Durand in Paris that he was composing a work for the coming Shrove Tuesday, and confessing that he knew he should be working on his Third Symphony, but that this work was "such fun" ("... mais c'est si amusant!"). He had apparently intended to write the work for his students at the École Niedermeyer, but it was first performed at a private concert given by the cellist Charles Lebouc on Shrove Tuesday, 9 March 1886.

A second (private) performance was given on 2 April at the home of Pauline Viardot with an audience including Franz Liszt, a friend of the composer, who had expressed a wish to hear the work. There were other private performances, typically for the French mid-Lent festival of Mi-Carême, but Saint-Saëns was adamant that the work would not be published in his lifetime, seeing it as detracting from his "serious" composer image. He relented only for the famous cello solo The Swan, which forms the penultimate movement of the work, and which was published in 1887 in an arrangement by the composer for cello and solo piano (the original uses two pianos).

Saint-Saëns did specify in his will that the work should be published posthumously. Following his death in December 1921, the work was published by Durand in Paris in April 1922 and the first public performance was given on 25 February 1922 by Concerts Colonne (the orchestra of Édouard Colonne).[2]

Carnival has since become one of Saint-Saëns's best-known works, played by the original eleven instrumentalists, or more often with the full string section of an orchestra. Normally a glockenspiel substitutes for the rare glass harmonica. Ever popular with music teachers and young children, it is often recorded in combination with Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf or Britten's The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra.

Movements

There are fourteen movements, each representing a different animal or animals:

| ||||

I Introduction et marche royale du lion (Introduction and Royal March of the Lion)

Strings and two pianos: the introduction begins with the pianos playing a bold tremolo, under which the strings enter with a stately theme. The pianos play a pair of scales going in opposite directions to conclude the first part of the movement. The pianos then introduce a march theme that they carry through most of the rest of the introduction. The strings provide the melody, with the pianos occasionally taking low runs of octaves which suggest the roar of a lion, or high ostinatos. The two groups of instruments switch places, with the pianos playing a higher, softer version of the melody. The movement ends with a fortissimo note from all the instruments used in this movement.

II Poules et coqs (Hens and Roosters)

Strings without cello and double bass, two pianos, with clarinet: this movement is centered around a pecking theme played in the pianos and strings, which is quite reminiscent of chickens pecking at grain. The clarinet plays small solos above the rest of the players at intervals. The piano plays a very fast theme based on the crowing of a rooster's Cock a Doodle Doo.

III Hémiones (animaux véloces) (Wild Asses: Swift Animals)

Two pianos: the animals depicted here are quite obviously running, an image induced by the constant, feverishly fast up-and-down motion of both pianos playing scales in octaves. These are dziggetai, asses that come from Tibet and are known for their great speed.

IV Tortues (Tortoises)

Strings and piano: a satirical movement which opens with a piano playing a pulsing triplet figure in the higher register. The strings play a slow rendition of the famous 'Galop infernal' (commonly called the Can-can) from Offenbach's operetta Orpheus in the Underworld.

V L'éléphant (The Elephant)

Double bass and piano: this section is marked Allegro pomposo, the perfect caricature for an elephant. The piano plays a waltz-like triplet figure while the bass hums the melody beneath it. Like "Tortues," this is also a musical joke—the thematic material is taken from the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream and Berlioz's "Dance of the Sylphs" from The Damnation of Faust. The two themes were both originally written for high, lighter-toned instruments (flute and various other woodwinds, and violin, accordingly); the joke is that Saint-Saëns moves this to the lowest and heaviest-sounding instrument in the orchestra, the double bass.

VI Kangourous (Kangaroos)

Two pianos: the main figure here is a pattern of 'hopping' fifths preceded by grace notes. When the fifths ascend, the tempo gradually speeds up and the dynamics get louder, and when the fifths descend, the tempo gradually slows down and the dynamics get quieter.

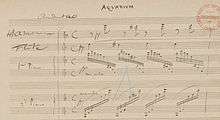

VII Aquarium

Two violins, viola, cello (string quartet), two pianos, flute, and glass harmonica: this is one of the more musically rich movements. The melody is played by the flute, backed by the strings, on top of tumultuous, glissando-like runs in the piano. The first piano plays a descending ten-on-one ostinato, in the style of the second of Chopin's études, while the second plays a six-on-one. These figures, plus the occasional glissando from the glass harmonica—often played on celesta or glockenspiel—are evocative of a peaceful, dimly-lit aquarium. According to British music journalist Fritz Spiegl, there is a recording of the movement featuring virtuoso harmonica player Tommy Reilly—apparently he was hired by mistake instead of a player of the glass harmonica. The recording in question is of the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra on the Naxos label.[3]

VIII Personnages à longues oreilles (Characters with Long Ears)

Two violins: this is the shortest of all the movements. The violins alternate playing high, loud notes and low, buzzing ones (in the manner of a donkey's braying "hee-haw"). Music critics have speculated that the movement is meant to compare music critics to braying donkeys.[4]

IX Le coucou au fond des bois (The Cuckoo in the Depths of the Woods)

Two pianos and clarinet: the pianos play large, soft chords while the clarinet plays a single two-note ostinato, over and over; a C and an A♭, mimicking the call of a cuckoo bird. Saint-Saëns states in the original score that the clarinetist should be offstage.

X Volière (Aviary)

Strings, piano and flute: the high strings take on a background role, providing a buzz in the background that is reminiscent of the background noise of a jungle. The cellos and basses play a pick up cadence to lead into most of the measures. The flute takes the part of the bird, with a trilling tune that spans much of its range. The pianos provide occasional pings and trills of other birds in the background. The movement ends very quietly after a long ascending chromatic scale from the flute.

XI Pianistes (Pianists)

Strings and two pianos: this movement is a glimpse of what few audiences ever get to see: the pianists practicing their scales. The scales of C, D♭, D and E♭ are covered. Each one starts with a trill on the first and second note, then proceeds in scales with a few changes in the rhythm. Transitions between keys are accomplished with a blasting chord from all the instruments between scales. In some performances, the later, more difficult, scales are deliberately played increasingly out of time. The original edition has a note by the editors instructing the players to imitate beginners and their awkwardness.[5] After the four scales, the key changes back to C, where the pianos play a moderate speed trill-like pattern in thirds, in the style of Charles-Louis Hanon or Carl Czerny, while the strings play a small part underneath. This movement is unusual in that the last three blasted chords do not resolve the piece, but rather lead into the next movement.

XII Fossiles (Fossils)

Strings, two pianos, clarinet, and xylophone: here, Saint-Saëns mimics his own composition, the Danse macabre, which makes heavy use of the xylophone to evoke the image of skeletons playing card games, the bones clacking together to the beat. The musical themes from Danse macabre are also quoted; the xylophone and the violin play much of the melody, alternating with the piano and clarinet. The piano part is especially difficult here—octaves that jump in quick thirds. Allusions to "Ah! vous dirai-je, Maman" (better known in the English-speaking world as Twinkle Twinkle Little Star), the French nursery rhymes "Au clair de la lune", and "J'ai du bon tabac" (the piano plays the same melody upside down), the popular anthem Partant pour la Syrie, as well as the aria Una voce poco fa from Rossini's The Barber of Seville can also be heard. The musical joke in this movement, according to Leonard Bernstein's narration on his recording of the work with the New York Philharmonic, is that the musical pieces quoted are the fossils of Saint-Saëns's time.

"Le cygne" (The Swan)

"Le cygne" performed by John Michel Camille Saint-Saëns's "Le cygne" (The Swan)

A novelty arrangement for cello and marimba performed by Alisa Weilerstein and Jason Yoder at the White House Evening of Classical Music (2009-11-04) Camille Saint-Saëns's "Le cygne" (The Swan)

Audio only Weilerstein and Yoder version | |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

XIII Le cygne (The Swan)

Two pianos and cello: the lushly romantic cello solo (which evokes the swan elegantly gliding over the water) is played over rippling sixteenths in one piano and rolled chords in the other (said to represent the swan's feet, hidden from view beneath the water, propelling it along).

A staple of the cello repertoire, this is one of the most well-known movements of the suite, usually in the version for cello with solo piano which was the only publication of this work in Saint-Saëns's lifetime. More than twenty other arrangements of this movement have also been published, with solo instruments ranging from flute to alto saxophone.

A short ballet, The Dying Swan, was choreographed in 1905 by Mikhail Fokine to this movement and performed by Anna Pavlova. Pavlova gave some 4,000 performances of the dance and "swept the world."[6]

XIV Final (Finale)

Full ensemble: the finale opens on the same tremolo notes in the pianos as in the introduction, which are soon reinforced by the wind instruments, the glass harmonica and the xylophone. The strings build the tension with a few low notes, leading to glissandi by the piano, then a pause before the lively main melody is introduced. The Finale is somewhat reminiscent of an American carnival of the 19th century, with one piano always maintaining a bouncy eighth-note rhythm. Although the melody is relatively simple, the supporting harmonies are ornamented in the style that is typical of Saint-Saëns' compositions for piano; dazzling scales, glissandi and trills. Many of the previous movements are quoted here from the introduction, the lion, the asses, hens, and kangaroos. The work ends with a series of six "Hee Haws" from the Jackasses, as if to say that the Jackass has the last laugh, before the final strong group of C major chords.

Musical allusions

As the title suggests, the work follows a zoological program and progresses from the first movement, Introduction et marche royale du lion, through portraits of elephants and donkeys ("Those with Long Ears") to a finale reprising many of the earlier motifs.

Several of the movements are of humorous intent:

- Poules et coqs uses the theme of Jean-Philippe Rameau's harpsichord piece La poule ("The Hen") from his Suite in G major, but in a quite less elegant mood.

- Pianistes depicts piano students practicing scales.

- Tortues makes good use of the well-known "Galop infernal" from Jacques Offenbach's operetta Orpheus in the Underworld, playing the usually breakneck-speed melody at a slow, drooping pace.

- L'éléphant uses a theme from Hector Berlioz's "Danse des sylphes" (from his work The Damnation of Faust) played in a much lower register than usual as a double bass solo. The piece also quotes the Scherzo from Felix Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream. It is heard at the end of the bridge section.

- Fossiles quotes Saint-Saëns' own Danse macabre as well as three nursery rhymes, "J'ai du bon tabac", "Ah! vous dirai-je, Maman" (Twinkle Twinkle Little Star) and "Au clair de la lune", also the song "Partant pour la Syrie" and Rossini's aria, "Una voce poco fa" from The Barber of Seville.

- The Personnages à longues oreilles section is thought to be directed at music critics: they are also supposedly the last animals heard during the finale, braying.

Ogden Nash verses

In 1949, Ogden Nash wrote a set of humorous verses to accompany each movement for a Columbia Masterworks recording of Carnival of the Animals conducted by Andre Kostelanetz. They were recited on the original album by Noël Coward, dubbed over or spliced in between sections of the previously recorded music. [7]

The poems are now often included when the work is performed, though usually recited before each piece. The conclusion of the verse for the "Fossils", for example, fits perfectly with the punchline-like first bar of the music:

- At midnight in the museum hall

- The fossils gathered for a ball

- There were no drums or saxophones,

- But just the clatter of their bones,

- A rolling, rattling, carefree circus

- Of mammoth polkas and mazurkas.

- Pterodactyls and brontosauruses

- Sang ghostly prehistoric choruses.

- Amid the mastodontic wassail

- I caught the eye of one small fossil.

- "Cheer up, sad world," he said, and winked—

- "It's kind of fun to be extinct."

A Modern Menagerie

In 2014 the English contemporary music organisation New Music in the South West (NMSW) commissioned a set of responses to the 14 movements of Carnival of the Animals.[8] The pieces, collectively known as A Modern Menagerie, were premièred by the Bristol Ensemble on 7 September 2014 at St. George’s, Bristol. The programme consisted of the original Saint-Saëns movements interleaved with the contemporary responses under the title Carnival of the Animals meets A Modern Menagerie.[9]

A number of the composers have taught or studied music at the University of Bristol, including John Pickard (current Professor of Composition), Geoff Poole, Michael Ellison, Julian Leeks and Manos Charalabopoulos. Two of the movements were composed by the finalists of the NMSW Young Composers’ Prize 2014.

The full list of movements is as follows:

- Introduction and Lion’s Royal March – Manos Charalabopoulos

- Poules et coqs – Sam Pradalie*

- Wild Asses – Andy Keenan

- Tortoise – Julian Leeks

- Elephant – Anna Meredith

- Kangaroos (2) – Jean Hasse

- Aquarium: A Penguin in Istanbul – Michael Ellison

- Myisi – Litha Efthymiou

- The Wood Pigeon: presiding over the entire garden – Sara Garrard

- Volière – Emily Potter†

- Fossils 2: Jurassic Tango – Geoffrey Poole

- (After) Pianists – Jean-Paul Metzger

- The Swan – Jolyon Laycock

- Finale: Dance of the Animals – John Pickard

- † = winner NMSW Young Composers’ Prize 2014

* = runner up

- † = winner NMSW Young Composers’ Prize 2014

The Wiggles

In 2016, The Wiggles released The Carnival of the Animals, its narration was written and performed by Simon Pryce. The Album was performed by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, and introduced children to classical music and instruments.

References

- ↑ Stegemann, Michael. Camille Saint-Saëns and the French solo concerto from 1850 to 1920. Translator Ann C. Sherwin. Amadeus Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-931340-35-7.

- ↑ Sabina Teller Ratner (25 April 2002). Camille Saint-Saens 1835–1921: A Thematic Catalogue of his Complete Works Volume I: The Instrumental Works. Oxford University Press. p. 185ff. ISBN 978-0-19-816320-6. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Prokofiev: Peter And The Wolf / Britten: Young Person's Guide To Orchestra / Saint-Saens: Carnival: Ondrej Lenard: MP3 Downloads". Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "Carnival of the Animals", The Listener, 18: 104, 1937-07-14, retrieved 2011-03-30

- ↑ "Les exécutants devront imiter le jeu d'un débutant et sa gaucherie." "Complete full score" (PDF). Paris: Durand & Cie. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ Frankenstein, Alfred. "The Carnival of the Animals" (liner notes). Capitol SP 8537 and reissued on Seraphim S-60214.

- ↑ http://www.discogs.com/André-Kostelanetz-And-His-Orchestra-Noël-Coward-Ogden-Nash-Saint-Saëns-Ravel-Carnival-Of-The-Anim/release/7472182

- ↑ "Modern Menagerie", NMSW

- ↑ "St. George's, Bristol Brochure Sep–Dec 2014", St. George's

External links

- The Carnival of the Animals on IMDb

- Fantasia 2000 on IMDb

- The Carnival of the Animals: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Video Performance of Le Cygne by Julian Lloyd Webber

- Bond discography – Born, featuring the "Aquarium" movement as "Oceanic"

- 2011 recording for organ and piano combined, by David Owen Norris and David Coram

- NY Theatre Ballet Children's Study Guide (PDF), featuring Ogden Nash verses

- Les Deux Love Orchestra's version of L'Aquarium