Le Testament de Villon

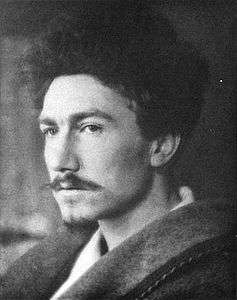

Le Testament de Villon is an opera written by American poet Ezra Pound.

In 1919, when he was 34, Pound began charting his path as a novice composer, writing privately that he intended a revolt against the impressionistic music of Claude Debussy. An autodidact, Pound described his working method as "improving a system by refraining from obedience to all its present 'laws'."[1] With only a few formal lessons in music composition, Pound produced a small body of work, including a setting of Dante's sestina, "Al poco giorno", for violin. His most important output is the pair of operas: Le Testament de Villon, a setting of François Villon's long poem of that name, which dates from 1461; and Cavalcanti, a setting of 11 poems by Guido Cavalcanti (c. 1250–1300). Pound began composing the Villon with the help of Agnes Bedford, a London pianist and vocal coach.[2] Though the work is notated in Bedford's hand, Pound scholar Robert Hughes has been able to determine that Pound was artistically responsible for the work's overall dramatic and acoustic design.

Background

Pound's The Cantos contains music and bears a title that could be translated as The Songs—although it never is. Pound was influenced early by the troubadour Marcabrun and the motz el sons of troubadour poetry,[3] about which musicologist John Stevens wrote, "melody and poem existed in a state of the closest symbiosis, obeying the same laws and striving in their different media for the same sound-ideal – armonia."[4] In his essays, Pound wrote of rhythm as "the hardest quality of a man's style to counterfeit".[5] However Pound was tone deaf according to William Carlos Williams who wrote, "he knows nothing of music being tone-deaf. That's what makes him a musician".[6]

During his years in Paris (1921–1924), Pound formed close friendships with the American pianist and composer George Antheil, and Antheil's touring partner, the American concert violinist Olga Rudge. Pound championed Antheil's music and asked his help in devising a system of micro-rhythms that would more accurately render the vitalistic speech rhythms of Villon's Old French for Le Testament. The resulting collaboration of 1923 used irregular meters that were considerably more elaborate than Stravinsky's benchmarks of the period, Le Sacre du Printemps (1913) and L'Histoire du Soldat (1918). For example, "Heaulmiere", one of the opera's key arias, at a tempo of quarter note = M.M. 88, moves from 2/8 to 25/32 to 3/8 to 2/4 meter (bars 25–28), making it difficult for performers to hear the current bar of music and anticipate the upcoming bar. Rudge performed in the 1924 and 1926 Paris preview concerts of Le Testament, but insisted to Pound that the meter was impractical.

Style

In Le Testament there is no predictability of manner; no comfort zone for singer or listener; no rests or breath marks. Though Pound stays within the hexatonic scale to evoke the feel of troubadour melodies, modern invention runs throughout, from the stream of unrelenting dissonance in the mother's prayer to the grand shape of the work's aesthetic arc over a period of almost an hour. The rhythm carries the emotion. The music admits the corporeal rhythms (the score calls for human bones to be used in the percussion part); scratches, hiccoughs, and counter-rhythms lurch against each other—an offense to courtly etiquette. With "melody against ground tone and forced against another melody",[7] as Pound puts it, the work spawns a polyphony in polyrhythms that ignores traditional laws of harmony. It was a test of Pound's ideal of an "absolute" and "uncounterfeitable" rhythm conducted in the laboratory of someone obsessed with the relationship between words and music.

Pound's statement, "Rhythm is a FORM cut into TIME, as a design is determined SPACE",[8] distinguishes his 20th century medievalism from Antheil's SPACE/TIME theory of modern music, which sought pure abstraction. Antheil's system of time organization is inherently biased for complex, asymmetric, and fast tempi; it thrives on innovation and surprise. Pound's more open system allows for any sequence of pitches; it can accommodate older styles of music with their symmetry, repetition, and more uniform tempi, as well as newer methods, such as the asymmetrical micro-metrical divisions of rhythm created for Le Testament. Pound was a friend of Igor Stravinsky.

Reception

After hearing a concert performance of Le Testament in 1926, Virgil Thomson praised Pound's accomplishment. "The music was not quite a musician's music", he wrote, "though it may well be the finest poet's music since Thomas Campion... Its sound has remained in my memory."[9]

Robert Hughes has remarked that where Le Testament explores a Webernesque pointillistic orchestration and derives its vitality from complex rhythms, Cavalcanti (1931) thrives on extensions of melody. Based on the lyric love poetry of Guido Cavalcanti, the opera's numbers are characterized by a challenging bel canto, into which Pound incorporates a number of tongue-in-cheek references to Verdi and a musical motive that gestures to Stravinsky's neo-classicism. By this time his relationship with Antheil had considerably cooled, and Pound, in his gradual acquisition of technical self-sufficiency, was free to emulate certain aspects of Stravinsky. Cavalcanti demands attention to its varying cadences, to a recurring leitmotif, and to a symbolic use of octaves. The play of octaves creates a surrealist straining against the limits of established laws of composition, history, physiology, reason, and love.

References

- ↑ Cited in: Fisher, 19

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 238

- ↑ Mundye, Charles (2008). "‘Motz el Son’: Pound’s musical modernism and the interpretation of medieval song". Abstract. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Stevens, 423

- ↑ Pound, Ezra (2005). The Spirit of Romance. New York: New Directions. p. 103. ISBN 0-8112-1646-2.

- ↑ Carpenter, p. 912

- ↑ Fisher 2002, p. 34

- ↑ Pound, Ezre. "Treatise on Metre". Cited in Elder, Bruce (1998). The Films of Stan Brakhage in the American Tradition of Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Charles Olson. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-88920-275-3.

- ↑ Cited in Fisher 2002, p. 20

Sources

- This article by Margaret Fisher is reproduced from the booklet MINDREADER, Spring 2001, a newsletter published by Other Minds, San Francisco, pages 3-5.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1988a). A Serious Character: the life of Ezra Pound. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-41678-7.

- Fisher, Margaret (2002). Ezra Pound's Radio Operas. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-262-06226-7.

- Pound, Ezra (2005). The Spirit of Romance. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-1646-2.

- Stevens, John (1986). Words and Music in the Middle Ages. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-521-33904-9.

- Stock, Noel (1970). The LIfe of Ezra Pound. New York: Pantheon Books.

Further reading

- Ingman, Michael (1999). "Pound and Music" in The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound Ed. Ira Nadel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.