Lazarus of Bethany

| Saint Lazarus of Bethany | |

|---|---|

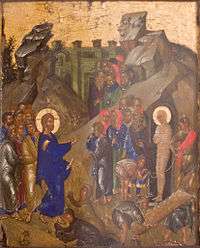

|

Christ Raising of Lazarus, Athens, 12–13th Century | |

| Four-days dead, Friend of Christ | |

| Venerated in |

Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church Eastern Catholic Churches Anglican Communion Lutheran Church Islam |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Sometimes vested as an apostle, sometimes as a bishop. In the scene of his resurrection, he is portrayed tightly bound in mummified clothes, which resemble swaddling bands |

Lazarus of Bethany, also known as Saint Lazarus or Lazarus of the Four Days, is the subject of a prominent miracle of Jesus in the Gospel of John, in which Jesus restores him to life four days after his death. The Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions offer varying accounts of the later events of his life.

In the context of the seven signs in the Gospel of John, the Raising of Lazarus is the climactic narrative: exemplifying the power of Jesus "over the last and most irresistible enemy of humanity—death. For this reason it is given a prominent place in the gospel."[6]

A figure named Lazarus (Latinised from the Aramaic: אלעזר, Elʿāzār, cf. Heb. Eleazar—"God is my help"[7]) is also mentioned in the Gospel of Luke. The two Biblical characters named "Lazarus" have sometimes been conflated historically, but are generally understood to be two separate people.

The name Lazarus is frequently used in science and popular culture in reference to apparent restoration to life; for example, the scientific term Lazarus taxon denotes organisms that reappear in the fossil record after a period of apparent extinction. There are also numerous literary uses of the term.

The Raising of Lazarus

Narrative

The biblical narrative of the Raising of Lazarus is found in chapter 11 of the Gospel of John.[8] Lazarus is introduced as a follower of Jesus, who lives in the town of Bethany near Jerusalem.[9] He is identified as the brother of the sisters Mary and Martha. The sisters send word to Jesus that Lazarus, "he whom thou lovest," is ill.[10] Instead of immediately traveling to Bethany, according to the narrator, Jesus intentionally remains where he is for two more days before beginning the journey.

When Jesus arrives in Bethany, he finds that Lazarus is dead and has already been in his tomb for four days. He meets first with Martha and Mary in turn. Martha laments that Jesus did not arrive soon enough to heal her brother and Jesus replies with the well-known statement, "I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die".[11] Later the narrator here gives the famous simple phrase, "Jesus wept".[12]

In the presence of a crowd of Jewish mourners, Jesus comes to the tomb. Over the objections of Martha, Jesus has them roll the stone away from the entrance to the tomb and says a prayer. He then calls Lazarus to come out and Lazarus does so, still wrapped in his grave-cloths. Jesus then calls for someone to remove the grave-cloths, and let him go.

The narrative ends with the statement that many of the witnesses to this event "believed in him." Others are said to report the events to the religious authorities in Jerusalem.

The Gospel of John mentions Lazarus again in chapter 12. Six days before the Passover on which Jesus is crucified, Jesus returns to Bethany and Lazarus attends a supper that Martha, his sister, serves.[13] Jesus and Lazarus together attract the attention of many Jews and the narrator states that the chief priests consider having Lazarus put to death because so many people are believing in Jesus on account of this miracle.[14]

The miracle of the raising of Lazarus, the longest coherent narrative in John aside from the Passion, is the climax of John's "signs". It explains the crowds seeking Jesus on Palm Sunday, and leads directly to the decision of Caiaphas and the Sanhedrin to kill Jesus.

It is notable that at John 11:11, Jesus indicates to his disciples that Lazarus has fallen asleep. The disciples thought Jesus meant Lazurus was actually sleeping in verse 12. Then, in verse 14, Jesus speaks plainly and tells them that "Lazurus has died". This is just one account where death is likened to sleep and a state of unconsciousness.

A resurrection story that is very similar is also found in the controversial Secret Gospel of Mark, although the young man is not named there specifically. Some scholars believe that the Secret Mark version represents an earlier form of the canonical story found in John.

Depictions in art

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Resurrection of Lazarus. |

The Raising of Lazarus is a popular subject in religious art.[15] Two of the most famous paintings are those of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (c. 1609) and Sebastiano del Piombo (1516). Among other prominent depictions of Lazarus are works by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Ivor Williams, and Lazarus Breaking His Fast by Walter Sickert.

- Paintings of the Resurrection of Lazarus

The Resurrection of Lazarus. Byzantine icon, late 14th – early 15th century, (From the Collection of G. Gamon-Gumun, Russian museum)

The Resurrection of Lazarus. Byzantine icon, late 14th – early 15th century, (From the Collection of G. Gamon-Gumun, Russian museum) The Resurrection of Lazarus, Russian icon, 15th century, Novgorod school (State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg)

The Resurrection of Lazarus, Russian icon, 15th century, Novgorod school (State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg) The Raising of Lazarus, Oil on canvas, c. 1517–1519, Sebastiano del Piombo (National Gallery, London)

The Raising of Lazarus, Oil on canvas, c. 1517–1519, Sebastiano del Piombo (National Gallery, London) The Raising of Lazarus, Oil on canvas, c. 1609, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Museo Regionale, Messina)

The Raising of Lazarus, Oil on canvas, c. 1609, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Museo Regionale, Messina) The Raising of Lazarus, 1630–1631, Rembrandt van Rijn (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles)

The Raising of Lazarus, 1630–1631, Rembrandt van Rijn (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles) The Raising of Lazarus, 1540–1545, Giuseppe Salviati

The Raising of Lazarus, 1540–1545, Giuseppe Salviati_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) The Raising of Lazarus (after Rembrandt), Oil on paper, 1890, Vincent van Gogh (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam)

The Raising of Lazarus (after Rembrandt), Oil on paper, 1890, Vincent van Gogh (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) The Raising of Lazarus, 1857, Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat

The Raising of Lazarus, 1857, Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat_Cropped.jpg) The Raising of Lazarus illumination on parchment, c. 1504

The Raising of Lazarus illumination on parchment, c. 1504

Tomb of Lazarus in Bethany

The reputed first tomb of Lazarus at al-Eizariya in the West Bank (generally believed to be the biblical Bethany) continues to be a place of pilgrimage to this day. Several Christian churches have existed at the site over the centuries. Since the 16th century, the site of the tomb has been occupied by the al-Uzair Mosque. The adjacent Roman Catholic Church of Saint Lazarus, designed by Antonio Barluzzi and built between 1952 and 1955 under the auspices of the Franciscan Order, stands upon the site of several much older ones. In 1965, a Greek Orthodox church was built just west of the tomb.

The entrance to the tomb today is via a flight of uneven rock-cut steps from the street. As it was described in 1896, there were twenty-four steps from the then-modern street level, leading to a square chamber serving as a place of prayer, from which more steps led to a lower chamber believed to be the tomb of Lazarus.[16] The same description applies today.[17][18]

The first mention of a church at Bethany is in the late 4th century, but both the historian Eusebius of Caesarea[19] (c. 330) and the Bordeaux pilgrim do mention the tomb of Lazarus. In 390 Jerome mentions a church dedicated to Saint Lazarus, called the Lazarium. This is confirmed by the pilgrim Egeria in about the year 410. Therefore, the church is thought to have been built between 333 and 390.[20] The present-day gardens contain the remnants of a mosaic floor from the 4th-century church.[21] The Lazarium was destroyed by an earthquake in the 6th century, and was replaced by a larger church. This church survived intact until the Crusader era.

In 1143 the existing structure and lands were purchased by King Fulk and Queen Melisende of Jerusalem and a large Benedictine convent dedicated to Mary and Martha was built near the tomb of Lazarus. After the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, the convent was deserted and fell into ruin with only the tomb and barrel vaulting surviving. By 1384, a simple mosque had been built on the site.[18] In the 16th century, the Ottomans built the larger al-Uzair Mosque to serve the town's (now Muslim) inhabitants and named it in honor of the town's patron saint, Lazarus of Bethany.[21]

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913, there were scholars who questioned the reputed site of the ancient village (though this was discounted by the Encyclopedia's author):

Some believe that the present village of Bethany does not occupy the site of the ancient village; but that it grew up around the traditional cave which they suppose to have been at some distance from the house of Martha and Mary in the village; Zanecchia (La Palestine d'aujourd'hui, 1899, I, 445ff.) places the site of the ancient village of Bethany higher up on the southeastern slope of the Mount of Olives, not far from the accepted site of Bethphage, and near that of the Ascension. It is quite certain that the present village formed about the traditional tomb of Lazarus, which is in a cave in the village. The identification of this cave as the tomb of Lazarus is merely possible; it has no strong intrinsic or extrinsic authority. The site of the ancient village may not precisely coincide with the present one, but there is every reason to believe that it was in this general location."[22]

Additional traditions about Lazarus of Bethany

While there is no further mention of Lazarus in the Bible, the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions offer varying accounts of the later events of his life. He is most commonly associated with Cyprus, where he is said to have become the first bishop of Kition (Larnaka), and Provence, where he is said to have been the first bishop of Marseille.

Bishop of Kition

According to Eastern Orthodox Church tradition, sometime after the Resurrection of Christ, Lazarus was forced to flee Judea because of rumoured plots on his life and came to Cyprus. There he was appointed by Paul and Barnabas as the first bishop of Kition (present-day Larnaka). He lived there for thirty more years,[23] and on his death was buried there for the second and last time.[24]

Further establishing the apostolic nature of Lazarus' appointment was the story that the bishop's omophorion was presented to Lazarus by the Virgin Mary, who had woven it herself. Such apostolic connections were central to the claims to autocephaly made by the bishops of Kition—subject to the patriarch of Jerusalem—during the period 325–431. The church of Kition was declared self-governing in 431 AD at the Third Ecumenical Council.[25]

According to tradition, Lazarus never smiled during the thirty years after his resurrection, worried by the sight of unredeemed souls he had seen during his four-day stay in Hades. The only exception was, when he saw someone stealing a pot, he smilingly said: "the clay steals the clay."[1][24]

In 890, a tomb was found in Larnaca bearing the inscription "Lazarus the friend of Christ". Emperor Leo VI of Byzantium had Lazarus' remains transferred to Constantinople in 898. The transfer was apostrophized by Arethas, bishop of Caesarea, and is commemorated by the Orthodox Church each year on October 17.

In recompense to Larnaca, Emperor Leo had the Church of St. Lazarus, which still exists today, erected over Lazarus' tomb. The marble sarcophagus can be seen inside the church under the Holy of Holies.

After the sacking of Constantinople by the Franks during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Crusaders carried the saint's relics to Marseilles, France as part of the booty of war. From there, "later on, they disappeared and up to the present day they have not been traced."[24]

In the 16th century, a Russian monk from the Monastery of Pskov visited St. Lazarus's tomb in Larnaca and took with him a small piece of the relics. Perhaps that piece led to the erection of the St. Lazarus chapel at the Pskov Monastery (Spaso-Eleazar Monastery, Pskov),[note 1] where it is kept today.[26]

On November 23, 1972, human remains in a marble sarcophagus were discovered under the altar, during renovation works in the church of Church of St. Lazarus at Larnaka, and were identified as part of the saint's relics.[27][note 2]

In June 2012 the Church of Cyprus gave a part of the holy relics of St. Lazarus to a delegation of the Russian Orthodox Church, led by Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, after a four-day visit to Cyprus. The relics were brought to Moscow and were given to Archbishop Arseniy of Istra, who took them to the Zachatievsky monastery (Conception Convent), where they were put up for veneration.[29]

Bishop of Marseille

In the West, according to an alternative medieval tradition (centered in Provence), Lazarus, Mary, and Martha were "put out to sea by the Jews hostile to Christianity in a vessel without sails, oars, or helm, and after a miraculous voyage landed in Provence at a place called today the Saintes-Maries."[30] The family is then said to separate and go in different parts of southeastern Gaul to preach; Lazarus goes to Marseilles. Converting many people to Christianity there, he becomes the first Bishop of Marseille. During the persecution of Domitian, he is imprisoned and beheaded in a cave beneath the prison Saint-Lazare. His body is later translated to Autun, where he is buried in the Autun Cathedral, dedicated to Lazarus as Saint Lazare. However, the inhabitants of Marseilles claim to be in possession of his head which they still venerate.[30]

Pilgrims also visit another purported tomb of Lazarus at the Vézelay Abbey in Burgundy.[31] In the Abbey of the Trinity at Vendôme, a phylactery was said to contain a tear shed by Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus.

The Golden Legend, compiled in the 13th century, records the Provençal tradition. It also records a grand lifestyle imagined for Lazarus and his sisters (note that therein Lazarus' sister Mary is conflated with Mary Magdalene):

Mary Magdalene had her surname of Magdalo, a castle, and was born of right noble lineage and parents, which were descended of the lineage of kings. And her father was named Cyrus, and her mother Eucharis. She with her brother Lazarus, and her sister Martha, possessed the castle of Magdalo, which is two miles from Nazareth, and Bethany, the castle which is nigh to Jerusalem, and also a great part of Jerusalem, which, all these things they departed among them. In such wise that Mary had the castle Magdalo, whereof she had her name Magdalene. And Lazarus had the part of the city of Jerusalem, and Martha had to her part Bethany. And when Mary gave herself to all delights of the body, and Lazarus entended all to knighthood, Martha, which was wise, governed nobly her brother's part and also her sister's, and also her own, and administered to knights, and her servants, and to poor men, such necessities as they needed. Nevertheless, after the ascension of our Lord, they sold all these things.[32]

The 15th-century poet Georges Chastellain draws on the tradition of the unsmiling Lazarus:[33] "He whom God raised, doing him such grace, the thief, Mary's brother, thereafter had naught but misery and painful thoughts, fearing what he should have to pass". (Le pas de la mort, VI[34]).

Liturgical commemorations

Lazarus is honored as a saint by those Christian churches which keep the commemoration of saints, although on different days, according to local traditions.

In Christian funerals the idea of the deceased being raised by the Lord as Lazarus was raised is often expressed in prayer.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Orthodox Church and Byzantine Catholic Church commemorate Lazarus on Lazarus Saturday,[1] the day before Palm Sunday, which is a moveable feast day. This day, together with Palm Sunday, hold a unique position in the church year, as days of joy and triumph between the penitence of Great Lent and the mourning of Holy Week.[35] During the preceding week, the hymns in the Lenten Triodion track the sickness and then the death of Lazarus, and Christ's journey from beyond Jordan to Bethany. The scripture readings and hymns for Lazarus Saturday focus on the resurrection of Lazarus as a foreshadowing of the Resurrection of Christ, and a promise of the General Resurrection. The Gospel narrative is interpreted in the hymns as illustrating the two natures of Christ: his humanity in asking, "Where have ye laid him?",[36] and his divinity by commanding Lazarus to come forth from the dead.[37] Many of the Resurrectional hymns of the normal Sunday service, which are omitted on Palm Sunday, are chanted on Lazarus Saturday. During the Divine Liturgy, the Baptismal Hymn, "As many as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ",[38] is sung in place of the Trisagion. Although the forty days of Great Lent end on the day before Lazarus Saturday, the day is still observed as a fast; however, it is somewhat mitigated. In Russia, it is traditional to eat caviar on Lazarus Saturday.

Lazarus is also commemorated on the liturgical calendar of the Orthodox Church on the fixed feast day of March 17,[2][note 3] while the translation of his relics from Cyprus to Constantinople in the year 898 AD[40] is observed on October 17.[3][39][note 4]

Roman Catholicism

No celebration of Saint Lazarus is included on the General Roman Calendar, but he is celebrated, together with his sister Mary of Bethany, on July 29, the memorial of their sister Martha.[41] Earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology placed him among the saints of December 17.[42]

In Cuba, the celebration of San Lázaro on December 17 is a major festival. The date is celebrated with a pilgrimage to a chapel housing an image Saint Lazarus, one of Cuba's most sacred icons, in the village of El Rincon, outside Havana.[43]

Anglicanism

Lazarus is commemorated in the Calendars of some Anglican provinces. In the Church of England his feast is kept on 29 July under the title "Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, Companions of Our Lord", and has the status of a lesser festival,[44] and as such is provided with proper lectionary readings and collect.

Lutheranism

Lazarus is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on 29 July together with Mary and Martha.

Conflation with the beggar Lazarus

The name "Lazarus" also appears in the Gospel of Luke in the parable of Lazarus and Dives, which is attributed to Jesus.[45] Also called "Dives and Lazarus", or "The Rich Man and the Beggar Lazarus", the narrative tells of the relationship (in life and in death) between an unnamed rich man and a poor beggar named Lazarus.

Historically within Christianity, the begging Lazarus of the parable (feast day June 21) and Lazarus of Bethany (feast day December 17) have often been conflated, with some churches celebrating a blessing of dogs, associated with the beggar, on December 17, the date associated with Lazarus of Bethany.[46] However, they are generally understood to be two separate characters. Allusions to Lazarus as a poor beggar taken to the "Bosom of Abraham" should be understood as referring to the Lazarus mentioned in Luke, rather than the Lazarus who rose from the dead in John.

This conflation can be found in Romanesque iconography carved on portals in Burgundy and Provence. For example, at the west portal of the Church of St. Trophime at Arles, the beggar Lazarus is enthroned as St. Lazarus. Similar examples are found at the church at Avallon, the central portal at Vézelay, and the portals of the cathedral of Autun.[47]

Order of Saint Lazarus

The Military and Hospitaller Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem (OSLJ) is a religious/military order of chivalry which originated in a leper hospital founded by Knights Hospitaller in the twelfth century by Crusaders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Sufferers of leprosy regarded the beggar Lazarus (of Luke 16:19-31) as their patron saint and usually dedicated their hospices to him.[48]

In Islam

Lazarus also appeared in medieval Islamic tradition, in which he was honored as a pious companion of Jesus. Although the Quran mentions no figure named Lazarus, among the miracles with which it credits Jesus includes the raising of people from the dead (III, 43/49). Muslim lore frequently detailed these miraculous narratives of Jesus, but mentioned Lazarus only occasionally. Al-Ṭabarī, for example, in his Taʾrīk̲h̲ talks of these miracles in general.[49] Al-T̲h̲aʿlabī, however, related, closely following St. John's Gospel: "Lazarus [Al-ʿĀzir] died, his sister sent to inform Jesus, Jesus came three (in the Gospel, four) days after his death, went with his sister to the tomb in the rock and caused Lazarus to arise; children were born to him". Similarly, in Ibn al-At̲h̲īr, the resurrected man is called "ʿĀzir",which is another Arabic rendering of "Lazarus."

Bibliography

Ṭabarī, i, 187, 731, 739

Ibn al-At̲h̲īr, i, 122, 123

T̲h̲aʿlabī, Ḳiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, Cairo 1325/1907-8, ii, 307. On the name Elʿazar, Eliezer, ʿĀzar, see S. Fraenkel, in ZDMG, lvi (1902) 71-3

J. Horovitz, in Hebrew Union College Annual, ii (1925), 157, 161

idem, Koranische Untersuchungen, Berlin 1926, 12, 85, 86.

Lazarus as Babalu Aye in Santería

Via syncretism, Lazarus (or more precisely the conflation of the two figures named "Lazarus") has become an important figure in Santería as the Yoruba deity Babalu Aye. Like the beggar of the Christian Gospel of Luke, Babalu-Aye represents someone covered with sores licked by dogs who was healed by divine intervention.[43][50] Silver charms known as the crutch of St. Lazarus or standard Roman Catholic-style medals of St. Lazarus are worn as talismans to invoke the aid of the syncretized deity in cases of medical suffering, particularly for people with AIDS.[50] In Santería, the date associated with St. Lazarus is December 17,[43] despite Santería's reliance on the iconography associated with the begging saint whose feast day is June 21.[46]

In culture

Well known in Western culture from their respective biblical tales, both figures named Lazarus (Lazarus of Bethany and the Beggar Lazarus of "Lazarus and Dives"), have appeared countless times in music, writing and art. The majority of the references are to Lazarus of Bethany.

20th Century literary allusions to Lazarus occur in fiction including Truman Capote's short story "A Tree of Night" in A Tree of Night and Other Stories (1945) and John Knowles's novel A Separate Peace (1959). It occurs in 20th Century poetry including Leonid Andreyev's book-length poem "Lazarus" (1906)[51][52] T.S. Eliot's poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" (1915), Edwin Arlington Robinson's poem "Lazarus" (1920),[53] and Sylvia Plath's poem "Lady Lazarus" published in her posthumous book Ariel (1965). It also appears in the memoir Witness (1952) by Whittaker Chambers (who acknowledged the influence of Dostoevsky's works), which opens its first chapter, "In 1937, I began, like Lazarus, the impossible return."[54]

Science fiction allusions to Lazarus occur in Robert A. Heinlein's Lazarus Long novels (1941–1987), Walter M. Miller, Jr.'s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1960), and Frank Herbert's The Lazarus Effect (1983).

Richard Zimler's bestselling novel The Gospel According to Lazarus (2016) is written from the perspective of Lazarus himself. The book presents Yeshua ben Yosef (Jesus' Hebrew name) as an early Jewish mystic and explores the deep friendship between Lazarus and Yeshua, who - within the fictional setting - have been best friends since childhood.

In music, a popular retelling of the biblical Lazarus story from the point of view of Lazarus in heaven is the 1984 gospel story-song "Lazarus Come Forth" by Contemporary Christian Music artist Carman.[55][56] A modern reinterpretation of the story is the title track to the album "Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!" by the Australian alternative band Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Several other bands have composed songs titled "Lazarus" in allusion to the resurrection story, including Porcupine Tree, Conor Oberst, Circa Survive, Chimaira, moe., Placebo, and David Bowie (written while he was terminally ill).[57]

Lazarus is sometimes referenced in political figures returning to power in unlikely circumstances. When John Howard lost the leadership of the Liberal Party of Australia, he rated his chances of regaining it as "Lazarus with a triple bypass".[58] Howard did regain the leadership and went on to become Prime Minister of Australia. Former President of Haiti, Jean Bertrand Aristide, was termed the "Haitian Lazarus" by journalist Amy Wilentz, in her description of his return to Haiti from exile and the political significance of this event.[59]

The scientific term "Lazarus taxon", which denotes organisms that reappear in the fossil record after a period of apparent extinction. "Lazarus syndrome" refers to an event in which a person spontaneously returns to life (the heart starts beating again) after resuscitation has been given up. The Lazarus sign is a reflex which can occur in a brain-dead person, thus giving the appearance that they have returned to life.

The Commodore Amiga's operating system's disk repair program Diskdoctor occasionally renames a disk "Lazarus" if it feels it has done a particularly good job of rescuing damaged files.[60]

In the Batman comics, Ra's al Ghul uses the Lazarus Pits to revitalize himself and keep him in a perpetual state of fitness and relative youth.

See also

Notes

- ↑ (in Russian) Спасо-Елеазаровский монастырь. Russian Wikipedia.

- ↑ In 1970 a fire that broke out in Church of St. Lazarus at Larnaka destroyed almost all of the internal furnishings of the church.[28] Subsequent archaeological excavations and renovations led to the discovery of a portion of the saint's relics.

- ↑ In the Synaxarion of Constantinople and in the Lavreotic Codex, reference is made to the "Raising of Lazarus" – the Holy and Just Lazarus, the friend of Christ.[2] The entry for October 17 in the Prologue from Ohrid also states that "Lazarus's principle feasts are on March 17 and Lazarus Saturday during Great Lent."[39]

- ↑ "...Under today's date is commemorated the translation of his relics from the island of Cyprus to Constantinople. This occurred when Emperor Leo the Wise built the Church of St. Lazarus in Constantinople, and translated Lazarus's relics there in the year 890. When, after almost a thousand years, Lazarus's grave in the town of Kition on Cyprus was unearthed, a marble tablet was found with the inscription: "Lazarus of the Four Days, the friend of Christ."[39]

References

- 1 2 3 Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ἀνάστασις τοῦ Λαζάρου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- 1 2 3 Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Λάζαρος ὁ Δίκαιος, ὁ φίλος τοῦ Χριστοῦ. 17 ΜΑΡΤΙΟΥ. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- 1 2 Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ἀνακομιδὴ καὶ Κατάθεσις τοῦ Λειψάνου τοῦ Ἁγίου καὶ Δικαίου Λαζάρου. 17 Οκτωβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ The Roman Martyrology. Transl. by the Archbishop of Baltimore. Last Edition, According to the Copy Printed at Rome in 1914. Revised Edition, with the Imprimatur of His Eminence Cardinal Gibbons. Baltimore: John Murphy Company, 1916. p. 387.

- ↑ The Benedictine Monks of St. Augustine's Abbey, Ramsgate (Comp.). The Book of Saints: A Dictionary of Servants of God Canonised by the Catholic Church: Extracted from The Roman and Other Martyrologies. London: A & C Black Ltd., 1921. p. 163.

- ↑ Tenney, Merrill C. Kenneth L. Barker & John Kohlenberger III, ed. Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House.

- ↑ William Barclay, The Parables of Jesus, Westminster John Knox Press, 1999, ISBN 0-664-25828-X, pp. 92–98.

- ↑ John 11:1–46

- ↑ John 11:1

- ↑ John 11:3

- ↑ John 11:25, KJV

- ↑ John 11:35, KJV

- ↑ John 12:2

- ↑ John 12:9–11

- ↑ For the treatment of this subject in Western European art, see the discussion in Franco Mormando, "Tintoretto's Recently Rediscovered Raising of Lazarus, in The Burlington Magazine, v. 142 (2000): pp. 624–29.

- ↑ In The Biblical World 8.5 (November 1896:40).

- ↑ Modern Bethany, by Albert Storme, Franciscan Cyberspot.

- 1 2 "Sacred Destinations" Archived 2009-08-20 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ The Onomastikon of Eusebius and the Madaba Map, By Leah Di Segni. First published in: The Madaba Map Centenary, Jerusalem, 1999, pp. 115–20.

- ↑ Bethany in Byzantine Times I and Bethany in Byzantine Times II, by Albert Storme, Franciscan Cyberspot.

- 1 2 Mariam Shahin (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. p. 332. ISBN 1-56656-557-X.

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Bethany". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Bethany". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Chev. C. Savona-Ventura (KLJ, CMLJ, BCrLJ). Lazarus of Bethany. Grand Priory of the Maltese Island: Military & Hospitaller Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem. December 2009. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Michaelides, M.G. "Saint Lazarus, The Friend Of Christ And First Bishop Of Kition", Larnaca, Cyprus, 1984. Reprinted by Fr. Demetrios Serfes at St. Lazarus The Friend Of Christ And First Bishop Of Kition, Cyprus Archived 2009-09-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Roberson, Fr. Ronald G., (C.S.P.). The Orthodox Church of Cyprus. CNEWA United States. 26 June 2007.

- ↑ St. Lazarus Church & Ecclesiastical Museum, Larnaca. Cyprus Tourism Organisation. p. 4. Retrieved: 2013-04-17.

- ↑ St. Lazarus Church & Ecclesiastical Museum, Larnaca. Cyprus Tourism Organisation. p. 14. Retrieved: 2013-04-17.

- ↑ St. Lazarus' relics brought to Moscow from Cyprus. Interfax-Religion. 13 June 2012, 13:32.

- ↑ St. Lazarus' Relics Brought to Moscow from Cyprus. Pravoslavie.ru. Moscow, June 13, 2012.

- 1 2

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Lazarus of Bethany". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Lazarus of Bethany". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑

- ↑ "Of Mary Magdalene", Legenda Aurea, Book IV.

- ↑ Huizinga, the Waning of the Middle Ages p. 147

- ↑ p. 59

- ↑ Archimandrite Kallistos Ware and Mother Mary, Tr., The Lenten Triodion (St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, South Canaan, Pennsylvania, 2002, ISBN 1-878997-51-3), p. 57.

- ↑ (John 11:34)

- ↑ (John 11:43)

- ↑ (Romans 6:3)

- 1 2 3 Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović. October 17 – The Prologue from Ohrid. (Serbian Orthodox Church Diocese of Western America). Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- ↑ Translation of the relics of St Lazarus "of the Four Days in the Tomb" the Bishop of Kiteia on Cyprus. OCA – Lives of the Saints. Retrieved: 2013-04-17.

- ↑ Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001 ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3), p. 398

- ↑ December 17, Roman Martyrology (1749).

- 1 2 3 With sackcloth and rum, Cubans hail Saint Lazarus Archived 2008-04-20 at the Wayback Machine., December 17, 1998. Reuters news story.

- ↑ Common Worship, published by Church House Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7151-2000-X, p. 11.

- ↑ Luke 16:19–31

- 1 2 Money talks: folklore in the public sphere Archived 2008-04-21 at the Wayback Machine. December 2005, Folklore magazine.

- ↑ Richard Hamann, "Lazarus in Heaven" The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 63 No. 364 (July 1933), pp. 3–5, 8–11

- ↑ "History" Archived 2012-07-01 at the Wayback Machine., official international website of the Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem. Retrieved on 2009-09-14.

- ↑ Ṭabarī, Taʾrīk̲h̲, i, 187, 731, 739

- 1 2 Lazarus

- ↑ Andreyev, Leonid (1906). Lazarus. MacMillan.

- ↑ "Leonid N. Andreyev". The Literature Network. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ Robinson, Edwin Arlington (1920). The Three Taverns: A Book of Poems. New York: MacMillan. pp. 109–20.

- ↑ Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 799 (total). LCCN 52005149.

- ↑ Carman Bio, MPCA promotional material.

- ↑ Comin' On Strong discography.

- ↑ Paulson, Michael (13 January 2016). "After David Bowie's Death, 'Lazarus' Holds New Meaning for Fans". New York Times. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ↑ "Thoughts of a bypassed Lazarus", The Age, Melbourne, 29 February 2004, retrieved 25 July 2007

- ↑ Wilentz, Amy. The Haitian Lazarus. NY Times (Op-Ed). March 15, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.amigahistory.co.uk/d.html