Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM (/ˈlɒrəns kɜːr ɒˈlɪvieɪ/; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, dominated the British stage of the mid-20th century. He also worked in films throughout his career, playing more than fifty cinema roles. Late in his career, he had considerable success in television roles.

His family had no theatrical connections, but Olivier's father, a clergyman, decided that his son should become an actor. After attending a drama school in London, Olivier learned his craft in a succession of acting jobs during the late 1920s. In 1930 he had his first important West End success in Noël Coward's Private Lives, and he appeared in his first film. In 1935 he played in a celebrated production of Romeo and Juliet alongside Gielgud and Peggy Ashcroft, and by the end of the decade he was an established star. In the 1940s, together with Richardson and John Burrell, Olivier was the co-director of the Old Vic, building it into a highly respected company. There his most celebrated roles included Shakespeare's Richard III and Sophocles's Oedipus. In the 1950s Olivier was an independent actor-manager, but his stage career was in the doldrums until he joined the avant garde English Stage Company in 1957 to play the title role in The Entertainer, a part he later played on film. From 1963 to 1973 he was the founding director of Britain's National Theatre, running a resident company that fostered many future stars. His own parts there included the title role in Othello (1964) and Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (1970).

Among Olivier's films are Wuthering Heights (1939), Rebecca (1940), and a trilogy of Shakespeare films as actor-director: Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948), and Richard III (1955). His later films included The Shoes of the Fisherman (1968), Sleuth (1972), Marathon Man (1976), and The Boys from Brazil (1978). His television appearances included an adaptation of The Moon and Sixpence (1960), Long Day's Journey into Night (1973), Love Among the Ruins (1975), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1976), Brideshead Revisited (1981) and King Lear (1983).

Olivier's honours included a knighthood (1947), a life peerage (1970) and the Order of Merit (1981). For his on-screen work he received four Academy Awards, two British Academy Film Awards, five Emmy Awards and three Golden Globe Awards. The National Theatre's largest auditorium is named in his honour, and he is commemorated in the Laurence Olivier Awards, given annually by the Society of London Theatre. He was married three times, to the actresses Jill Esmond from 1930 to 1940, Vivien Leigh from 1940 to 1960, and Joan Plowright from 1961 until his death.

Life and career

Family background and early life (1907–24)

Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, the youngest of the three children of the Revd Gerard Kerr Olivier (1869–1939) and his wife Agnes Louise, née Crookenden (1871–1920).[1] Their elder children were Sybille (1901–1989) and Gerard Dacres "Dickie" (1904–1958).[2] His great-great-grandfather was of French Huguenot descent, and Olivier came from a long line of Protestant clergymen.[lower-alpha 1] Gerard Olivier had begun a career as a schoolmaster, but in his thirties he discovered a strong religious vocation and was ordained as a priest of the Church of England.[4] He practised extremely high church, ritualist Anglicanism and liked to be addressed as "Father Olivier". This made him unacceptable to most Anglican congregations,[4] and the only church posts he was offered were temporary, usually deputising for regular incumbents in their absence. This meant a nomadic existence, and for Laurence's first few years, he never lived in one place long enough to make friends.[5]

In 1912, when Olivier was five, his father secured a permanent appointment as assistant priest at St Saviour's, Pimlico. He held the post for six years, and a stable family life was at last possible.[6] Olivier was devoted to his mother, but not to his father, whom he found a cold and remote parent.[7] Nevertheless, he learned a great deal of the art of performing from him. As a young man Gerard Olivier had considered a stage career and was a dramatic and effective preacher. Olivier wrote that his father knew "when to drop the voice, when to bellow about the perils of hellfire, when to slip in a gag, when suddenly to wax sentimental ... The quick changes of mood and manner absorbed me, and I have never forgotten them."[8]

In 1916, after attending a series of preparatory schools, Olivier passed the singing examination for admission to the choir school of All Saints, Margaret Street, in central London. His elder brother was already a pupil, and Olivier gradually settled in, though he felt himself to be something of an outsider.[9] The church's style of worship was (and remains) Anglo-Catholic, with emphasis on ritual, vestments and incense.[10] The theatricality of the services appealed to Olivier,[lower-alpha 2] and the vicar encouraged the students to develop a taste for secular as well as religious drama.[12] In a school production of Julius Caesar in 1917, the ten-year-old Olivier's performance as Brutus impressed an audience that included Lady Tree, the young Sybil Thorndike, and Ellen Terry, who wrote in her diary, "The small boy who played Brutus is already a great actor."[13] He later won praise in other schoolboy productions, as Maria in Twelfth Night (1918) and Katherine in The Taming of the Shrew (1922).[14]

From All Saints, Olivier went on to St Edward's School, Oxford, from 1920 to 1924. He made little mark until his final year, when he played Puck in the school's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream; his performance was a tour de force that won him popularity among his fellow pupils.[15][lower-alpha 3] In January 1924, his brother left England to work in India as a rubber planter. Olivier missed him greatly and asked his father how soon he could follow. He recalled in his memoirs that his father replied, "Don't be such a fool, you're not going to India, you're going on the stage."[17][lower-alpha 4]

Early acting career (1924–29)

In 1924 Gerard Olivier, a habitually frugal man, told his son that not only must he gain admission to the Central School of Speech Training and Dramatic Art, but he must also gain a scholarship with a bursary to cover his tuition fees and living expenses.[19] Olivier's sister had been a student there and was a favourite of Elsie Fogerty, the founder and principal of the school. Olivier later speculated that it was on the strength of this that Fogerty agreed to award him the bursary.[19][lower-alpha 5]

One of Olivier's contemporaries at the school was Peggy Ashcroft, who observed he was "rather uncouth in that his sleeves were too short and his hair stood on end but he was intensely lively and great fun".[21] By his own admission, he was not a very conscientious student, but Fogerty liked him and later said that he and Ashcroft stood out among her many pupils.[22] On leaving the school after a year, Olivier gained work with small touring companies before being taken on in 1925 by Sybil Thorndike and her husband, Lewis Casson, as a bit-part player, understudy and assistant stage manager for their London company.[23] He modelled his performing style on that of Gerald du Maurier, of whom he said, "He seemed to mutter on stage but had such perfect technique. When I started I was so busy doing a du Maurier that no one ever heard a word I said. The Shakespearean actors one saw were terrible hams like Frank Benson."[24] His concern to speak naturally and avoid what he called "singing" Shakespeare's verse was the cause of much frustration in his early career, with critics regularly decrying his delivery.[25]

In 1926, on Thorndike's recommendation, Olivier joined the Birmingham Repertory Company.[26] His biographer Michael Billington describes the Birmingham company as "Olivier's university", where in his second year he was given the chance to play a wide range of important roles, including Tony Lumpkin in She Stoops to Conquer, the title role in Uncle Vanya, and Parolles in All's Well That Ends Well.[27] Billington adds that the engagement led to "a lifelong friendship with his fellow actor Ralph Richardson that was to have a decisive effect on the British theatre."[1]

While playing the juvenile lead in Bird in Hand at the Royalty Theatre in June 1928, Olivier began a relationship with Jill Esmond, the daughter of the actors Henry V. Esmond and Eva Moore.[28] Olivier later recounted that he thought "she would most certainly do excellent well for a wife ... I wasn't likely to do any better at my age and with my undistinguished track-record, so I promptly fell in love with her."[29]

In 1928 Olivier created the role of Stanhope in R. C. Sherriff's Journey's End, in which he scored a great success at its single Sunday night premiere.[30] He was offered the part in the West End production the following year, but turned it down in favour of the more glamorous role of Beau Geste in a stage adaptation of P. C. Wren's 1929 novel of the same name. Journey's End became a long-running success; Beau Geste failed.[1] The Manchester Guardian commented, "Mr. Laurence Olivier did his best as Beau, but he deserves and will get better parts. Mr. Olivier is going to make a big name for himself".[31] For the rest of 1929 Olivier appeared in seven plays, all of which were short-lived. Billington ascribes this failure rate to poor choices by Olivier rather than mere bad luck.[1][lower-alpha 6]

Rising star (1930–35)

In 1930, with his impending marriage in mind, Olivier earned some extra money with small roles in two films.[35] In April he travelled to Berlin to film the English-language version of The Temporary Widow, a crime comedy with Lilian Harvey,[lower-alpha 7] and in May he spent four nights working on another comedy, Too Many Crooks.[37] During work on the latter film, for which he was paid £60,[lower-alpha 8] he met Laurence Evans, who became his personal manager.[35] Olivier did not enjoy working in film, which he dismissed as "this anaemic little medium which could not stand great acting",[39] but financially it was much more rewarding than his theatre work.[40]

Olivier and Esmond married on 25 July 1930 at All Saints, Margaret Street,[41] although within weeks both realised they had erred. Olivier later recorded that the marriage was "a pretty crass mistake. I insisted on getting married from a pathetic mixture of religious and animal promptings. ... She had admitted to me that she was in love elsewhere and could never love me as completely as I would wish".[42][lower-alpha 9][lower-alpha 10] Olivier later recounted that following the wedding he did not keep a diary for ten years and never followed religious practices again, although he considered those facts to be "mere coincidence", unconnected to the nuptials.[45]

In 1930 Noël Coward cast Olivier as Victor Prynne in his new play Private Lives, which opened at the new Phoenix Theatre in London in September. Coward and Gertrude Lawrence played the lead roles, Elyot Chase and Amanda Prynne. Victor is a secondary character, along with Sybil Chase; the author called them "extra puppets, lightly wooden ninepins, only to be repeatedly knocked down and stood up again".[46] To make them credible spouses for Amanda and Elyot, Coward was determined that two outstandingly attractive performers should play the parts.[47] Olivier played Victor in the West End and then on Broadway; Adrianne Allen was Sybil in London, but could not go to New York, where the part was taken by Esmond.[48] In addition to giving the 23-year-old Olivier his first successful West End role, Coward became something of a mentor. In the late 1960s Olivier told Sheridan Morley:

He gave me a sense of balance, of right and wrong. He would make me read; I never used to read anything at all. I remember he said, "Right, my boy, Wuthering Heights, Of Human Bondage and The Old Wives' Tale by Arnold Bennett. That'll do, those are three of the best. Read them". I did. ... Noël also did a priceless thing, he taught me not to giggle on the stage. Once already I'd been fired for doing it, and I was very nearly sacked from the Birmingham Rep. for the same reason. Noël cured me; by trying to make me laugh outrageously, he taught me how not to give in to it.[lower-alpha 11] My great triumph came in New York when one night I managed to break Noël up on the stage without giggling myself."[50]

In 1931 RKO Pictures offered Olivier a two-film contract at $1,000 a week;[lower-alpha 12] he discussed the possibility with Coward, who, irked, told Olivier "You've no artistic integrity, that's your trouble; this is how you cheapen yourself."[52] He accepted and moved to Hollywood, despite some misgivings. His first film was the drama Friends and Lovers, in a supporting role, before RKO loaned him to Fox Studios for his first film lead, a British journalist in a Russia under martial law in The Yellow Passport, alongside Elissa Landi and Lionel Barrymore.[53] The cultural historian Jeffrey Richards describes Olivier's look as an attempt by Fox Studios to produce a likeness of Ronald Colman, and Colman's moustache, voice and manner are "perfectly reproduced".[54] Olivier returned to RKO to complete his contract with the 1932 drama Westward Passage, which was a commercial failure.[55] Olivier's initial foray into American films had not provided the breakthrough he hoped for; disillusioned with Hollywood, he returned to London, where he appeared in two British films, Perfect Understanding with Gloria Swanson and No Funny Business—in which Esmond also appeared. He was tempted back to Hollywood in 1933 to appear opposite Greta Garbo in Queen Christina, but was replaced after two weeks of filming because of a lack of chemistry between the two.[56]

Olivier's stage roles in 1934 included Bothwell in Gordon Daviot's Queen of Scots, which was only a moderate success for him and for the play, but led to an important engagement for the same management (Bronson Albery) shortly afterwards. In the interim he had a great success playing a thinly disguised version of the American actor John Barrymore in Edna Ferber's Theatre Royal. His success was vitiated by his breaking an ankle two months into the run, in one of the athletic, acrobatic stunts with which he liked to enliven his performances.[57]

Herbert Farjeon on the rival Romeos.[58]

In 1935, under Albery's management, John Gielgud staged Romeo and Juliet at the New Theatre, co-starring with Peggy Ashcroft, Edith Evans and Olivier. Gielgud had seen Olivier in Queen of Scots, spotted his potential, and now gave him a major step up in his career. For the first weeks of the run Gielgud played Mercutio and Olivier played Romeo, after which they exchanged roles.[lower-alpha 13] The production broke all box-office records for the play, running for 189 performances.[lower-alpha 14] Olivier was enraged at the notices after the first night, which praised the virility of his performance but fiercely criticised his speaking of Shakespeare's verse, contrasting it with his co-star's mastery of the poetry.[lower-alpha 15] The friendship between the two men was prickly, on Olivier's side, for the rest of his life.[61]

Old Vic and Vivien Leigh (1936–38)

In May 1936 Olivier and Richardson jointly directed and starred in a new piece by J. B. Priestley, Bees on the Boatdeck. Both actors won excellent notices, but the play, an allegory of Britain's decay, did not attract the public and closed after four weeks.[62] Later in the same year Olivier accepted an invitation to join the Old Vic company. The theatre, in an unfashionable location south of the Thames, had offered inexpensive tickets for opera and drama under its proprietor Lilian Baylis since 1912.[63] Her drama company specialised in the plays of Shakespeare, and many leading actors had taken very large cuts in their pay to develop their Shakespearean techniques there.[lower-alpha 16] Gielgud had been in the company from 1929 to 1931, and Richardson from 1930 to 1932.[65] Among the actors whom Olivier joined in late 1936 were Edith Evans, Ruth Gordon, Alec Guinness and Michael Redgrave.[66] In January 1937 he took the title role in an uncut version of Hamlet, in which once again his delivery of the verse was unfavourably compared with that of Gielgud, who had played the role on the same stage seven years previously to enormous acclaim.[lower-alpha 17] The Observer's Ivor Brown praised Olivier's "magnetism and muscularity" but missed "the kind of pathos so richly established by Mr Gielgud".[69] The reviewer in The Times found the performance "full of vitality", but at times "too light ... the character slips from Mr Olivier's grasp".[70]

After Hamlet, the company presented Twelfth Night in what the director, Tyrone Guthrie, summed up as "a baddish, immature production of mine, with Olivier outrageously amusing as Sir Toby and a very young Alec Guinness outrageous and more amusing as Sir Andrew".[71] Henry V was the next play, presented in May to mark the Coronation of George VI. A pacifist, as he then was, Olivier was as reluctant to play the warrior king as Guthrie was to direct the piece, but the production was a success, and Baylis had to extend the run from four to eight weeks.[72]

Following Olivier's success in Shakespearean stage productions, he made his first foray into Shakespeare on film in 1936, as Orlando in As You Like It, directed by Paul Czinner, "a charming if lightweight production", according to Michael Brooke of the British Film Institute's (BFI's) Screenonline.[73] The following year Olivier appeared alongside Vivien Leigh in the historical drama Fire Over England. He had first met Leigh briefly at the Savoy Grill and then again when she visited him during the run of Romeo and Juliet, probably early in 1936, and the two had begun an affair sometime that year.[74] Of the relationship, Olivier later said that "I couldn't help myself with Vivien. No man could. I hated myself for cheating on Jill, but then I had cheated before, but this was something different. This wasn't just out of lust. This was love that I really didn't ask for but was drawn into."[75] While his relationship with Leigh continued he conducted an affair with the actress Ann Todd,[76] and possibly had a homosexual fling with the actor Henry Ainley, according to the biographer Michael Munn.[77][lower-alpha 18]

In June 1937 the Old Vic company took up an invitation to perform Hamlet in the courtyard of the castle at Elsinore, where Shakespeare located the play. Olivier secured the casting of Leigh to replace Cherry Cottrell as Ophelia. Because of torrential rain the performance had to be moved from the castle courtyard to the ballroom of a local hotel, but the tradition of playing Hamlet at Elsinore was established, and Olivier was followed by, among others, Gielgud (1939), Redgrave (1950), Richard Burton (1954), Derek Jacobi (1979), Kenneth Branagh (1988) and Jude Law (2009).[82] Back in London, the company staged Macbeth, with Olivier in the title role. The stylised production by Michel Saint-Denis was not well liked, but Olivier had some good notices among the bad.[83] On returning from Denmark, Olivier and Leigh told their respective spouses about the affair and that their marriages were over; Esmond moved out of the marital house and in with her mother.[84] After Olivier and Leigh made a tour of Europe in mid 1937 they returned to separate film projects—A Yank at Oxford for her and The Divorce of Lady X for him—and moved into a property together in Iver, Buckinghamshire.[85]

Olivier returned to the Old Vic for a second season in 1938. For Othello he played Iago, with Richardson in the title role. Guthrie wanted to experiment with the theory that Iago's villainy is driven by suppressed homosexual love for Othello.[86] Olivier was willing to co-operate, but Richardson was not; audiences and most critics failed to spot the supposed motivation of Olivier's Iago, and Richardson's Othello seemed underpowered.[87] After that comparative failure, the company had a success with Coriolanus starring Olivier in the title role. The notices were laudatory, mentioning him alongside great predecessors such as Edmund Kean, William Macready and Henry Irving. The actor Robert Speaight described it as "Olivier's first incontestably great performance".[88] This was Olivier's last appearance on a London stage for six years.[88]

Hollywood and the Second World War (1938–44)

In 1938 Olivier joined Richardson to film the spy thriller Q Planes, released the following year. Frank Nugent, the critic for The New York Times, thought Olivier was "not quite so good" as Richardson, but was "quite acceptable".[89] In late 1938, lured by a salary of $50,000, the actor travelled to Hollywood to take the part of Heathcliff in the 1939 film Wuthering Heights, alongside Merle Oberon and David Niven.[90][lower-alpha 19] In less than a month Leigh had joined him, explaining that her trip was "partially because Larry's there and partially because I intend to get the part of Scarlett O'Hara"—the role in Gone with the Wind in which she was eventually cast.[91] Olivier did not enjoy making Wuthering Heights, and his approach to film acting, combined with a dislike for Oberon, led to tensions on set.[92] The director, William Wyler, was a hard taskmaster, and Olivier learned to remove what Billington described as "the carapace of theatricality" to which he was prone, replacing it with "a palpable reality".[1] The resulting film was a commercial and critical success that earned him a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor, and created his screen reputation.[93][lower-alpha 20] Caroline Lejeune, writing for The Observer, considered that "Olivier's dark, moody face, abrupt style, and a certain fine arrogance towards the world in his playing are just right" in the role,[95] while the reviewer for The Times wrote that Olivier "is a good embodiment of Heathcliff ... impressive enough on a more human plane, speaking his lines with real distinction, and always both romantic and alive."[96]

After returning to London briefly in mid-1939, the couple returned to America, Leigh to film the final takes for Gone with the Wind, and Olivier to prepare for filming of Alfred Hitchcock's Rebecca—although the couple had hoped to appear in it together.[97] Instead, Joan Fontaine was selected for the role of Mrs de Winter, as the producer David O. Selznick thought that not only was she more suitable for the role, but that it was best to keep Olivier and Leigh apart until their divorces came through.[98] Olivier followed Rebecca with Pride and Prejudice, in the role of Mr. Darcy. To his disappointment Elizabeth Bennet was played by Greer Garson rather than Leigh. He received good reviews for both films and showed a more confident screen presence than he had in his early work.[99] In January 1940 Olivier and Esmond were granted their divorce. In February, following another request from Leigh, her husband also applied for their marriage to be terminated.[100]

On stage, Olivier and Leigh starred in Romeo and Juliet on Broadway. It was an extravagant production, but a commercial failure.[101] In The New York Times Brooks Atkinson praised the scenery but not the acting: "Although Miss Leigh and Mr Olivier are handsome young people they hardly act their parts at all."[102] The couple had invested almost all their savings in the project, and its failure was a grave financial blow.[103] They were married in August 1940, at the San Ysidro Ranch in Santa Barbara.[104]

The war in Europe had been under way for a year and was going badly for Britain. After his wedding Olivier wanted to help the war effort. He telephoned Duff Cooper, the Minister of Information under Winston Churchill, hoping to get a position in Cooper's department. Cooper advised him to remain where he was and speak to the film director Alexander Korda, who was based in the US at Churchill's behest, with connections to British Intelligence.[105][lower-alpha 21] Korda—with Churchill's support and involvement—directed That Hamilton Woman, with Olivier as Horatio Nelson and Leigh in the title role. Korda saw that the relationship between the couple was strained. Olivier was tiring of Leigh's suffocating adulation, and she was drinking to excess.[106] The film, in which the threat of Napoleon paralleled that of Hitler, was seen by critics as "bad history but good British propaganda", according to the BFI.[107]

Olivier's life was under threat from the Nazis and pro-German sympathisers. The studio owners were concerned enough that Samuel Goldwyn and Cecil B. DeMille both provided support and security to ensure his safety.[108] On the completion of filming, Olivier and Leigh returned to Britain. He had spent the previous year learning to fly and had completed nearly 250 hours by the time he left America. He intended to join the Royal Air Force but instead made another propaganda film, 49th Parallel, narrated short pieces for the Ministry of Information, and joined the Fleet Air Arm because Richardson was already in the service. Richardson had gained a reputation for crashing aircraft, which Olivier rapidly eclipsed.[109] Olivier and Leigh settled in a cottage just outside RAF Worthy Down, where he was stationed with a training squadron; Noël Coward visited the couple and thought Olivier looked unhappy.[110] Olivier spent much of his time taking part in broadcasts and making speeches to build morale, and in 1942 he was invited to make another propaganda film, The Demi-Paradise, in which he played a Soviet engineer who helps improve British-Russian relationships.[111]

In 1943, at the behest of the Ministry of Information, Olivier began working on Henry V. Originally he had no intention of taking the directorial duties, but ended up directing and producing, in addition to taking the title role. He was assisted by an Italian internee, Filippo Del Giudice, who had been released to produce propaganda for the Allied cause.[112] The decision was made to film the battle scenes in neutral Eire, where it was easier to find the 650 extras. John Betjeman, the press attaché at the British embassy in Dublin, played a key liaison role with the Irish government in making suitable arrangements.[113] The film was released in November 1944. Brooke, writing for the BFI, considers that it "came too late in the Second World War to be a call to arms as such, but formed a powerful reminder of what Britain was defending."[114] The music for the film was written by William Walton, "a score that ranks with the best in film music", according to the music critic Michael Kennedy.[115] Walton also provided the music for Olivier's next two Shakespearean adaptations, Hamlet (1948) and Richard III (1955).[116] Henry V was warmly received by critics. The reviewer for The Manchester Guardian wrote that the film combined "new art hand-in-hand with old genius, and both superbly of one mind", in a film that worked "triumphantly".[117] The critic for The Times considered that Olivier "plays Henry on a high, heroic note and never is there danger of a crack", in a film described as "a triumph of film craft".[118] There were Oscar nominations for the film, including Best Picture and Best Actor, but it won none and Olivier was instead presented with a "Special Award".[119] He was unimpressed, and later commented that "this was my first absolute fob-off, and I regarded it as such."[120]

Co-directing the Old Vic (1944–48)

Throughout the war Tyrone Guthrie had striven to keep the Old Vic company going, even after German bombing in 1942 left the theatre a near-ruin. A small troupe toured the provinces, with Sybil Thorndike at its head. By 1944, with the tide of the war turning, Guthrie felt it time to re-establish the company in a London base and invited Richardson to head it.[121] Richardson made it a condition of accepting that he should share the acting and management in a triumvirate. Initially he proposed Gielgud and Olivier as his colleagues, but the former declined, saying, "It would be a disaster, you would have to spend your whole time as referee between Larry and me."[122][lower-alpha 22] It was finally agreed that the third member would be the stage director John Burrell. The Old Vic governors approached the Royal Navy to secure the release of Richardson and Olivier; the Sea Lords consented, with, as Olivier put it, "a speediness and lack of reluctance which was positively hurtful."[124]

The triumvirate secured the New Theatre for their first season and recruited a company. Thorndike was joined by, among others, Harcourt Williams, Joyce Redman and Margaret Leighton. It was agreed to open with a repertory of four plays: Peer Gynt, Arms and the Man, Richard III and Uncle Vanya. Olivier's roles were the Button Moulder, Sergius, Richard and Astrov; Richardson played Peer, Bluntschli, Richmond and Vanya.[125] The first three productions met with acclaim from reviewers and audiences; Uncle Vanya had a mixed reception, although The Times thought Olivier's Astrov "a most distinguished portrait" and Richardson's Vanya "the perfect compound of absurdity and pathos".[126] In Richard III, according to Billington, Olivier's triumph was absolute: "so much so that it became his most frequently imitated performance and one whose supremacy went unchallenged until Antony Sher played the role forty years later".[1] In 1945 the company toured Germany, where they were seen by many thousands of Allied servicemen; they also appeared at the Comédie-Française theatre in Paris, the first foreign company to be given that honour.[127] The critic Harold Hobson wrote that Richardson and Olivier quickly "made the Old Vic the most famous theatre in the Anglo-Saxon world."[128]

The second season, in 1945, featured two double bills. The first consisted of Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2. Olivier played the warrior Hotspur in the first and the doddering Justice Shallow in the second.[lower-alpha 23] He received good notices, but by general consent the production belonged to Richardson as Falstaff.[130] In the second double bill it was Olivier who dominated, in the title roles of Oedipus Rex and The Critic. In the two one-act plays his switch from searing tragedy and horror in the first half to farcical comedy in the second impressed most critics and audience members, though a minority felt that the transformation from Sophocles's bloodily blinded hero to Sheridan's vain and ludicrous Mr Puff "smacked of a quick-change turn in a music hall".[131] After the London season the company played both the double bills and Uncle Vanya in a six-week run on Broadway.[132]

The third, and final, London season under the triumvirate was in 1946–47. Olivier played King Lear, and Richardson took the title role in Cyrano de Bergerac. Olivier would have preferred the roles to be reversed, but Richardson did not wish to attempt Lear.[133] Olivier's Lear received good but not outstanding reviews. In his scenes of decline and madness towards the end of the play some critics found him less moving than his finest predecessors in the role.[134] The influential critic James Agate suggested that Olivier used his dazzling stage technique to disguise a lack of feeling, a charge that the actor strongly rejected, but which was often made throughout his later career.[135] During the run of Cyrano, Richardson was knighted, to Olivier's undisguised envy.[136] The younger man received the accolade six months later, by which time the days of the triumvirate were numbered. The high profile of the two star actors did not endear them to the new chairman of the Old Vic governors, Lord Esher. He had ambitions to be the first head of the National Theatre and had no intention of letting actors run it.[137] He was encouraged by Guthrie, who, having instigated the appointment of Richardson and Olivier, had come to resent their knighthoods and international fame.[138]

In January 1947 Olivier began working on his second film as a director, Hamlet (1948), in which he also took the lead role. The original play was heavily cut to focus on the relationships, rather than the political intrigue. The film became a critical and commercial success in Britain and abroad, although Lejeune, in The Observer, considered it "less effective than [Olivier's] stage work. ... He speaks the lines nobly, and with the caress of one who loves them, but he nullifies his own thesis by never, for a moment, leaving the impression of a man who cannot make up his own mind; here, you feel rather, is an actor-producer-director who, in every circumstance, knows exactly what he wants, and gets it".[139] Campbell Dixon, the critic for The Daily Telegraph thought the film "brilliant ... one of the masterpieces of the stage has been made into one of the greatest of films."[140] Hamlet became the first non-American film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, while Olivier won the Award for Best Actor.[141][142][lower-alpha 24]

In 1948 Olivier led the Old Vic company on a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand. He played Richard III, Sir Peter Teazle in Sheridan's The School for Scandal and Antrobus in Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth, appearing alongside Leigh in the latter two plays. While Olivier was on the Australian tour and Richardson was in Hollywood, Esher terminated the contracts of the three directors, who were said to have "resigned".[144] Melvyn Bragg in a 1984 study of Olivier, and John Miller in the authorised biography of Richardson, both comment that Esher's action put back the establishment of a National Theatre for at least a decade.[145] Looking back in 1971, Bernard Levin wrote that the Old Vic company of 1944 to 1948 "was probably the most illustrious that has ever been assembled in this country".[146] The Times said that the triumvirate's years were the greatest in the Old Vic's history;[147] as The Guardian put it, "the governors summarily sacked them in the interests of a more mediocre company spirit".[148]

Post-war (1948–51)

By the end of the Australian tour, both Leigh and Olivier were exhausted and ill, and he told a journalist, "You may not know it, but you are talking to a couple of walking corpses." Later he would comment that he "lost Vivien" in Australia,[149] a reference to Leigh's affair with the Australian actor Peter Finch, whom the couple met during the tour. Shortly afterwards Finch moved to London, where Olivier auditioned him and put him under a long-term contract with Laurence Olivier Productions. Finch and Leigh's affair continued on and off for several years.[150][151]

Although it was common knowledge that the Old Vic triumvirate had been dismissed,[152] they refused to be drawn on the matter in public, and Olivier even arranged to play a final London season with the company in 1949, as Richard III, Sir Peter Teazle, and Chorus in his own production of Anouilh's Antigone with Leigh in the title role.[1] After that, he was free to embark on a new career as an actor-manager. In partnership with Binkie Beaumont he staged the English premiere of Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire, with Leigh in the central role of Blanche DuBois. The play was condemned by most critics, but the production was a considerable commercial success, and led to Leigh's casting as Blanche in the 1951 film version.[153] Gielgud, who was a devoted friend of Leigh's, doubted whether Olivier was wise to let her play the demanding role of the mentally unstable heroine: "[Blanche] was so very like her, in a way. It must have been a most dreadful strain to do it night after night. She would be shaking and white and quite distraught at the end of it."[154]

Olivier talking to Kenneth Tynan in 1966[12]

The production company set up by Olivier took a lease on the St James's Theatre. In January 1950 he produced, directed and starred in Christopher Fry's verse play Venus Observed. The production was popular, despite poor reviews, but the expensive production did little to help the finances of Laurence Olivier Productions. After a series of box-office failures,[lower-alpha 25] the company balanced its books in 1951 with productions of Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra and Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra which the Oliviers played in London and then took to Broadway. Olivier was thought by some critics to be under par in both his roles, and some suspected him of playing deliberately below his usual strength so that Leigh might appear his equal.[156] Olivier dismissed the suggestion, regarding it as an insult to his integrity as an actor. In the view of the critic and biographer W. A. Darlington, he was simply miscast both as Caesar and Antony, finding the former boring and the latter weak. Darlington comments, "Olivier, in his middle forties when he should have been displaying his powers at their very peak, seemed to have lost interest in his own acting".[157] Over the next four years Olivier spent much of his time working as a producer, presenting plays rather than directing or acting in them.[157] His presentations at the St James's included seasons by Ruggero Ruggeri's company giving two Pirandello plays in Italian, followed by a visit from the Comédie-Française playing works by Molière, Racine, Marivaux and Musset in French.[158] Darlington considers a 1951 production of Othello starring Orson Welles as the pick of Olivier's productions at the theatre.[157]

Independent actor-manager (1951–54)

While Leigh made Streetcar in 1951, Olivier joined her in Hollywood to film Carrie, based on the controversial novel Sister Carrie; although the film was plagued by troubles, Olivier received warm reviews and a BAFTA nomination.[159] Olivier began to notice a change in Leigh's behaviour, and he later recounted that "I would find Vivien sitting on the corner of the bed, wringing her hands and sobbing, in a state of grave distress; I would naturally try desperately to give her some comfort, but for some time she would be inconsolable."[160] After a holiday with Coward in Jamaica, she seemed to have recovered, but Olivier later recorded, "I am sure that ... [the doctors] must have taken some pains to tell me what was wrong with my wife; that her disease was called manic depression and what that meant—a possibly permanent cyclical to-and-fro between the depths of depression and wild, uncontrollable mania.[161] He also recounted the years of problems he had experienced because of Leigh's illness, writing, "throughout her possession by that uncannily evil monster, manic depression, with its deadly ever-tightening spirals, she retained her own individual canniness—an ability to disguise her true mental condition from almost all except me, for whom she could hardly be expected to take the trouble."[162]

In January 1953 Leigh travelled to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to film Elephant Walk with Peter Finch. Shortly after filming started she suffered a breakdown, and returned to Britain where, between periods of incoherence, she told Olivier that she was in love with Finch, and had been having an affair with him;[163] she gradually recovered over a period of several months. As a result of the breakdown, many of the Oliviers' friends learned of her problems. Niven said she had been "quite, quite mad",[164] and in his diary, Coward expressed the view that "things had been bad and getting worse since 1948 or thereabouts."[165]

For the Coronation season of 1953, Olivier and Leigh starred in the West End in Terence Rattigan's Ruritanian comedy, The Sleeping Prince. It ran for eight months[166] but was widely regarded as a minor contribution to the season, in which other productions included Gielgud in Venice Preserv'd, Coward in The Apple Cart and Ashcroft and Redgrave in Antony and Cleopatra.[167][168]

Olivier directed his third Shakespeare film in September 1954, Richard III (1955), which he co-produced with Korda. The presence of four theatrical knights in the one film—Olivier was joined by Cedric Hardwicke, Gielgud and Richardson—led an American reviewer to dub it "An-All-Sir-Cast".[169] The critic for The Manchester Guardian described the film as a "bold and successful achievement",[170][171] but it was not a box-office success, which accounted for Olivier's subsequent failure to raise the funds for a planned film of Macbeth.[169] He won a BAFTA award for the role and was nominated for the Best Actor Academy Award, which Yul Brynner won.[172][173]

Last years with Leigh (1955–56)

In 1955 Olivier and Leigh were invited to play leading roles in three plays at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford. They began with Twelfth Night, directed by Gielgud, with Olivier as Malvolio and Leigh as Viola. Rehearsals were difficult, with Olivier determined to play his conception of the role despite the director's view that it was vulgar.[174] Gielgud later commented:

Somehow the production did not work. Olivier was set on playing Malvolio in his own particular rather extravagant way. He was extremely moving at the end, but he played the earlier scenes like a Jewish hairdresser, with a lisp and an extraordinary accent, and he insisted on falling backwards off a bench in the garden scene, though I begged him not to do it. ... But then Malvolio is a very difficult part.[175]

The next production was Macbeth. Reviewers were lukewarm about the direction by Glen Byam Shaw and the designs by Roger Furse, but Olivier's performance in the title role attracted superlatives.[176] To J. C. Trewin, Olivier's was "the finest Macbeth of our day"; to Darlington it was "the best Macbeth of our time".[177][178] Leigh's Lady Macbeth received mixed but generally polite notices,[177][179][180] although to the end of his life Olivier believed it to have been the best Lady Macbeth he ever saw.[181]

In their third production of the 1955 Stratford season, Olivier played the title role in Titus Andronicus, with Leigh as Lavinia. Her notices in the part were damning,[lower-alpha 26] but the production by Peter Brook and Olivier's performance as Titus received the greatest ovation in Stratford history from the first-night audience, and the critics hailed the production as a landmark in post-war British theatre.[183] Olivier and Brook revived the production for a continental tour in June 1957; its final performance, which closed the old Stoll Theatre in London, was the last time Leigh and Olivier acted together.[178]

Leigh became pregnant in 1956 and withdrew from the production of Coward's comedy South Sea Bubble.[184] The day after her final performance in the play she miscarried and entered a period of depression that lasted for months.[185] The same year Olivier decided to direct and produce a film version of The Sleeping Prince, retitled The Prince and the Showgirl. Instead of appearing with Leigh, he cast Marilyn Monroe as the showgirl. Although the filming was challenging because of Monroe's behaviour, the film was appreciated by the critics.[186]

Royal Court and Chichester (1957–63)

During the production of The Prince and the Showgirl, Olivier, Monroe and her husband, the American playwright Arthur Miller, went to see the English Stage Company's production of John Osborne's Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court. Olivier had seen the play earlier in the run and disliked it, but Miller was convinced that Osborne had talent, and Olivier reconsidered. He was ready for a change of direction; in 1981 he wrote:

I had reached a stage in my life that I was getting profoundly sick of—not just tired—sick. Consequently the public were, likely enough, beginning to agree with me. My rhythm of work had become a bit deadly: a classical or semi-classical film; a play or two at Stratford, or a nine-month run in the West End, etc etc. I was going mad, desperately searching for something suddenly fresh and thrillingly exciting. What I felt to be my image was boring me to death.[187]

Osborne was already at work on a new play, The Entertainer, an allegory of Britain's post-colonial decline, centred on a seedy variety comedian, Archie Rice. Having read the first act—all that was completed by then—Olivier asked to be cast in the part. He had for years maintained that he might easily have been a third-rate comedian called "Larry Oliver", and would sometimes play the character at parties. Behind Archie's brazen façade there is a deep desolation, and Olivier caught both aspects, switching, in the words of the biographer Anthony Holden, "from a gleefully tacky comic routine to moments of the most wrenching pathos".[188] Tony Richardson's production for the English Stage Company transferred from the Royal Court to the Palace Theatre in September 1957; after that it toured and returned to the Palace.[189] The role of Archie's daughter Jean was taken by three actresses during the various runs. The second of them was Joan Plowright, with whom Olivier began a relationship that endured for the rest of his life.[lower-alpha 27] Olivier said that playing Archie "made me feel like a modern actor again".[191] In finding an avant-garde play that suited him, he was, as Osborne remarked, far ahead of Gielgud and Ralph Richardson, who did not successfully follow his lead for more than a decade.[192][lower-alpha 28] Their first substantial successes in works by any of Osborne's generation were Alan Bennett's Forty Years On (Gielgud in 1968) and David Storey's Home (Richardson and Gielgud in 1970).[194]

Olivier received another BAFTA nomination for his supporting role in 1959's The Devil's Disciple.[173] The same year, after a gap of two decades, Olivier returned to the role of Coriolanus, in a Stratford production directed by the 28-year-old Peter Hall. Olivier's performance received strong praise from the critics for its fierce athleticism combined with an emotional vulnerability.[1] In 1960 he made his second appearance for the Royal Court company in Ionesco's absurdist play Rhinoceros. The production was chiefly remarkable for the star's quarrels with the director, Orson Welles, who according to the biographer Francis Beckett suffered the "appalling treatment" that Olivier had inflicted on Gielgud at Stratford five years earlier. Olivier again ignored his director and undermined his authority.[195] In 1960 and 1961 Olivier appeared in Anouilh's Becket on Broadway, first in the title role, with Anthony Quinn as the king, and later exchanging roles with his co-star.[1]

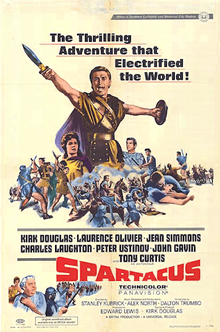

Two films featuring Olivier were released in 1960. The first—filmed in 1959—was Spartacus, in which he portrayed the Roman general, Marcus Licinius Crassus.[196] His second was The Entertainer, shot while he was appearing in Coriolanus; the film was well received by the critics, but not as warmly as the stage show had been.[197] The reviewer for The Guardian thought the performances were good, and wrote that Olivier "on the screen as on the stage, achieves the tour de force of bringing Archie Rice ... to life".[198] For his performance, Olivier was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.[199] He also made an adaptation of The Moon and Sixpence in 1960, winning an Emmy Award.[200]

The Oliviers' marriage was disintegrating during the late 1950s. While directing Charlton Heston in the 1960 play The Tumbler, Olivier divulged that "Vivien is several thousand miles away, trembling on the edge of a cliff, even when she's sitting quietly in her own drawing room", at a time when she was threatening suicide.[201] In May 1960 divorce proceedings started; Leigh reported the fact to the press and informed reporters of Olivier's relationship with Plowright.[202] The decree nisi was issued in December 1960, which enabled him to marry Plowright in March 1961.[203] A son, Richard, was born in December 1961; two daughters followed, Tamsin Agnes Margaret—born in January 1963—and Julie-Kate, born in July 1966.[204]

In 1961 Olivier accepted the directorship of a new theatrical venture, the Chichester Festival. For the opening season in 1962 he directed two neglected 17th-century English plays, John Fletcher's 1638 comedy The Chances and John Ford's 1633 tragedy The Broken Heart,[205] followed by Uncle Vanya. The company he recruited was forty strong and included Thorndike, Casson, Redgrave, Athene Seyler, John Neville and Plowright.[205] The first two plays were politely received; the Chekhov production attracted rapturous notices. The Times commented, "It is doubtful if the Moscow Arts Theatre itself could improve on this production."[206] The second Chichester season the following year consisted of a revival of Uncle Vanya and two new productions—Shaw's Saint Joan and John Arden's The Workhouse Donkey.[207] In 1963 Olivier received another BAFTA nomination for his leading role as a schoolteacher accused of sexually molesting a student in the film Term of Trial.[173]

National Theatre

1963–68

At around the time the Chichester Festival opened, plans for the creation of the National Theatre were coming to fruition. The British government agreed to release funds for a new building on the South Bank of the Thames.[1] Lord Chandos was appointed chairman of the National Theatre Board in 1962, and in August Olivier accepted its invitation to be the company's first director. As his assistants, he recruited the directors John Dexter and William Gaskill, with Kenneth Tynan as literary adviser or "dramaturge".[208] Pending the construction of the new theatre, the company was based at the Old Vic. With the agreement of both organisations, Olivier remained in overall charge of the Chichester Festival during the first three seasons of the National; he used the festivals of 1964 and 1965 to give preliminary runs to plays he hoped to stage at the Old Vic.[209]

The opening production of the National Theatre was Hamlet in October 1963, starring Peter O'Toole and directed by Olivier. O'Toole was a guest star, one of occasional exceptions to Olivier's policy of casting productions from a regular company. Among those who made a mark during Olivier's directorship were Michael Gambon, Maggie Smith, Alan Bates, Derek Jacobi and Anthony Hopkins. It was widely remarked that Olivier seemed reluctant to recruit his peers to perform with his company.[210] Evans, Gielgud and Paul Scofield guested only briefly, and Ashcroft and Richardson never appeared at the National during Olivier's time.[lower-alpha 29] Robert Stephens, a member of the company, observed, "Olivier's one great fault was a paranoid jealousy of anyone who he thought was a rival".[211]

In his decade in charge of the National, Olivier acted in thirteen plays and directed eight.[212] Several of the roles he played were minor characters, including a crazed butler in Feydeau's A Flea in Her Ear and a pompous solicitor in Maugham's Home and Beauty; the vulgar soldier Captain Brazen in Farquhar's 1706 comedy The Recruiting Officer was a larger role but not the leading one.[213] Apart from his Astrov in the Uncle Vanya, familiar from Chichester, his first leading role for the National was Othello, directed by Dexter in 1964. The production was a box-office success and was revived regularly over the next five seasons.[214] His performance divided opinion. Most of the reviewers and theatrical colleagues praised it highly; Franco Zeffirelli called it "an anthology of everything that has been discovered about acting in the past three centuries."[215] Dissenting voices included The Sunday Telegraph, which called it "the kind of bad acting of which only a great actor is capable ... near the frontiers of self-parody";[216] the director Jonathan Miller thought it "a condescending view of an Afro Caribbean person".[217] The burden of playing this demanding part at the same time as managing the new company and planning for the move to the new theatre took its toll on Olivier. To add to his load, he felt obliged to take over as Solness in The Master Builder when the ailing Redgrave withdrew from the role in November 1964.[218][lower-alpha 30] For the first time Olivier began to suffer from stage fright, which plagued him for several years.[221] The National Theatre production of Othello was released as a film in 1965, which earned four Academy Award nominations, including another for Best Actor for Olivier.[222]

During the following year Olivier concentrated on management, directing one production (The Crucible), taking the comic role of the foppish Tattle in Congreve's Love for Love, and making one film, Bunny Lake is Missing, in which he and Coward were on the same bill for the first time since Private Lives.[223] In 1966, his one play as director was Juno and the Paycock. The Times commented that the production "restores one's faith in the work as a masterpiece".[224] In the same year Olivier portrayed the Mahdi, opposite Heston as General Gordon, in the film Khartoum.[225]

In 1967 Olivier was caught in the middle of a confrontation between Chandos and Tynan over the latter's proposal to stage Rolf Hochhuth's Soldiers. As the play speculatively depicted Churchill as complicit in the assassination of the Polish prime minister Władysław Sikorski, Chandos regarded it as indefensible. At his urging the board unanimously vetoed the production. Tynan considered resigning over this interference with the management's artistic freedom, but Olivier himself stayed firmly in place, and Tynan also remained.[226] At about this time Olivier began a long struggle against a succession of illnesses. He was treated for prostate cancer and, during rehearsals for his production of Chekhov's Three Sisters he was hospitalised with pneumonia.[227] He recovered enough to take the heavy role of Edgar in Strindberg's The Dance of Death, the finest of all his performances other than in Shakespeare, in Gielgud's view.[228]

1968–74

Olivier had intended to step down from the directorship of the National Theatre at the end of his first five-year contract, having, he hoped, led the company into its new building. By 1968 because of bureaucratic delays construction work had not even begun, and he agreed to serve for a second five-year term.[229] His next major role, and his last appearance in a Shakespeare play, was as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, his first appearance in the work.[lower-alpha 31] He had intended Guinness or Scofield to play Shylock, but stepped in when neither was available.[231] The production by Jonathan Miller, and Olivier's performance, attracted a wide range of responses. Two different critics reviewed it for The Guardian: one wrote "this is not a role which stretches him, or for which he will be particularly remembered"; the other commented that the performance "ranks as one of his greatest achievements, involving his whole range".[232][233]

In 1969 Olivier appeared in two war films, portraying military leaders. He played Field Marshal French in the First World War film Oh! What a Lovely War, for which he won another BAFTA award,[173] followed by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding in Battle of Britain.[234] In June 1970 he became the first actor to be created a peer for services to the theatre.[235][236] Although he initially declined the honour, Harold Wilson, the incumbent prime minister, wrote to him, then invited him and Plowright to dinner, and persuaded him to accept.[237]

After this Olivier played three more stage roles: James Tyrone in Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night (1971–72), Antonio in Eduardo de Filippo's Saturday, Sunday, Monday and John Tagg in Trevor Griffiths's The Party (both 1973–74). Among the roles he hoped to play, but could not because of ill-health, was Nathan Detroit in the musical Guys and Dolls.[238] In 1972 he took leave of absence from the National to star opposite Michael Caine in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's film of Anthony Shaffer's Sleuth, which The Illustrated London News considered to be "Olivier at his twinkling, eye-rolling best";[239] both he and Caine were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor, losing to Marlon Brando in The Godfather.[240]

The last two stage plays Olivier directed were Jean Giradoux's Amphitryon (1971) and Priestley's Eden End (1974).[241] By the time of Eden End, he was no longer director of the National Theatre; Peter Hall took over on 1 November 1973.[242] The succession was tactlessly handled by the board, and Olivier felt that he had been eased out—although he had declared his intention to go—and that he had not been properly consulted about the choice of successor.[243] The largest of the three theatres within the National's new building was named in his honour, but his only appearance on the stage of the Olivier Theatre was at its official opening by the Queen in October 1976, when he made a speech of welcome, which Hall privately described as the most successful part of the evening.[244]

Later years (1975–89)

Olivier spent the last 15 years of his life in securing his finances and dealing with worsening health,[1] which included thrombosis and dermatomyositis, a degenerative muscle disorder.[245][246] Professionally, and to secure financial security, he made a series of advertisements for Polaroid cameras in 1972, although he stipulated that they must never be shown in Britain; he also took a number of cameo film roles, which were in "often undistinguished films", according to Billington.[247] Olivier's move from leading parts to supporting and cameo roles came about because his poor health meant he could not get the necessary long insurance for larger parts, with only short engagements in films available.[248]

Olivier's dermatomyositis meant he spent the last three months of 1974 in hospital, and he spent early 1975 slowly recovering and regaining his strength. When strong enough, he was contacted by the director John Schlesinger, who offered him the role of a Nazi torturer in the 1976 film Marathon Man. Olivier shaved his pate and wore oversized glasses to enlarge the look of his eyes, in a role that the critic David Robinson, writing for The Times, thought was "strongly played", adding that Olivier was "always at his best in roles that call for him to be seedy or nasty or both".[249] Olivier was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and won the Golden Globe of the same category.[250][251]

In the mid-1970s Olivier became increasingly involved in television work, a medium of which he was initially dismissive.[1] In 1973 he provided the narration for a 26-episode documentary, The World at War, which chronicled the events of the Second World War, and won a second Emmy Award for Long Day's Journey into Night (1973). In 1975 he won another Emmy for Love Among the Ruins.[200] The following year he appeared in adaptations of Tennessee Williams's Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Harold Pinter's The Collection.[252] In 1978 he appeared in the film The Boys from Brazil, playing the role of Ezra Lieberman, an ageing Nazi hunter; he received his eleventh Academy Award nomination. Although he did not win the Oscar, he was presented with an Honorary Award for his lifetime achievement.[253]

Olivier continued working in film into the 1980s, with roles in The Jazz Singer (1980), Inchon (1981), The Bounty (1984) and Wild Geese II (1985).[254] He continued to work in television; in 1981 he appeared as Lord Marchmain in Brideshead Revisited, winning another Emmy, and the following year he received his tenth and last BAFTA nomination in the television adaptation of John Mortimer's stage play A Voyage Round My Father.[173] In 1983 he played his last Shakespearean role as Lear in King Lear, for Granada Television, earning his fifth Emmy.[200] He thought the role of Lear much less demanding than other tragic Shakespearean heroes: "No, Lear is easy. He's like all of us, really: he's just a stupid old fart."[255] When the production was first shown on American television, the critic Steve Vineberg wrote:

Olivier seems to have thrown away technique this time—his is a breathtakingly pure Lear. In his final speech, over Cordelia's lifeless body, he brings us so close to Lear's sorrow that we can hardly bear to watch, because we have seen the last Shakespearean hero Laurence Olivier will ever play. But what a finale! In this most sublime of plays, our greatest actor has given an indelible performance. Perhaps it would be most appropriate to express simple gratitude.[256]

The same year he also appeared in a cameo alongside Gielgud and Richardson in Wagner, with Burton in the title role;[257] his final screen appearance was as an old, wheelchair-bound soldier in Derek Jarman's 1989 film War Requiem.[258]

After being ill for the last 22 years of his life, Olivier died of renal failure on 11 July 1989 aged 82 at his home near Steyning, West Sussex. His cremation was held three days later,[259] and a funeral was held in Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey in October that year.[246][260]

Awards, honours and memorials

In 1947 Olivier was appointed a Knight Bachelor, and in 1970 he was given a life peerage; the Order of Merit was conferred on him in 1981. He also received honours from foreign governments. In 1949 he was made Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog by the Danish King Frederik IX; the French appointed him Officier, Legion of Honour, in 1953; the Italian government created him Grande Ufficiale, Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, in 1953; and in 1971 he was granted the Order of Yugoslav Flag with Golden Wreath.[261]

From academic and other institutions, Olivier received honorary doctorates from the university of Tufts, Massachusetts (1946), Oxford (1957) and Edinburgh (1964). He was also awarded the Danish Sonning Prize in 1966, the Gold Medallion of the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities in 1968; and the Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts in 1976.[261][262][lower-alpha 32]

For his work in films, Olivier received four Academy Awards: an honorary award for Henry V (1947), a Best Actor award and one as producer for Hamlet (1948), and a second honorary award in 1979 to recognise his lifetime of contribution to the art of film. He was nominated for nine other acting Oscars and one each for production and direction.[263] He also won two British Academy Film Awards out of ten nominations,[lower-alpha 33] five Emmy Awards out of nine nominations,[lower-alpha 34] and three Golden Globe Awards out of six nominations.[lower-alpha 35] He was nominated once for a Tony Award (for best actor, as Archie Rice) but did not win.[200][265]

In February 1960, for his contribution to the film industry, Olivier was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame, with a star at 6319 Hollywood Boulevard;[266] he is included in the American Theater Hall of Fame.[267] In 1977 Olivier was awarded a British Film Institute Fellowship.[268]

In addition to the naming of the National Theatre's largest auditorium in Olivier's honour, he is commemorated in the Laurence Olivier Awards, bestowed annually since 1984 by the Society of West End Theatre.[261] In 1991 Gielgud unveiled a memorial stone commemorating Olivier in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey.[269] In 2007, the centenary of Olivier's birth, a life-sized statue of him was unveiled on the South Bank, outside the National Theatre;[270] the same year the BFI held a retrospective season of his film work.[271]

Technique and reputation

Olivier's acting technique was minutely crafted, and he was known for changing his appearance considerably from role to role. By his own admission, he was addicted to extravagant make-up,[272] and unlike Richardson and Gielgud, he excelled at different voices and accents.[273][lower-alpha 36] His own description of his technique was "working from the outside in";[275] he said, "I can never act as myself, I have to have a pillow up my jumper, a false nose or a moustache or wig ... I cannot come on looking like me and be someone else."[272] Rattigan described how at rehearsals Olivier "built his performance slowly and with immense application from a mass of tiny details".[276] This attention to detail had its critics: Agate remarked, "When I look at a watch it is to see the time and not to admire the mechanism. I want an actor to tell me Lear's time of day and Olivier doesn't. He bids me watch the wheels go round."[277]

.jpg)

Tynan remarked to Olivier, "you aren't really a contemplative or philosophical actor";[12] Olivier was known for the strenuous physicality of his performances in some roles. He told Tynan this was because he was influenced as a young man by Douglas Fairbanks, Ramon Navarro and John Barrymore in films, and Barrymore on stage as Hamlet: "tremendously athletic. I admired that greatly, all of us did. ... One thought of oneself, idiotically, skinny as I was, as a sort of Tarzan."[12][lower-alpha 37] According to Morley, Gielgud was widely considered "the best actor in the world from the neck up and Olivier from the neck down."[279] Olivier described the contrast thus: "I've always thought that we were the reverses of the same coin ... the top half John, all spirituality, all beauty, all abstract things; and myself as all earth, blood, humanity."[12]

Together with Richardson and Gielgud, Olivier was internationally recognised as one of the "great trinity of theatrical knights"[280] who dominated the British stage during the middle and later decades of the 20th century.[281] In an obituary tribute in The Times, Bernard Levin wrote, "What we have lost with Laurence Olivier is glory. He reflected it in his greatest roles; indeed he walked clad in it—you could practically see it glowing around him like a nimbus. ... no one will ever play the roles he played as he played them; no one will replace the splendour that he gave his native land with his genius."[282] Billington commented:

[Olivier] elevated the art of acting in the twentieth century ... principally by the overwhelming force of his example. Like Garrick, Kean, and Irving before him, he lent glamour and excitement to acting so that, in any theatre in the world, an Olivier night raised the level of expectation and sent spectators out into the darkness a little more aware of themselves and having experienced a transcendent touch of ecstasy. That, in the end, was the true measure of his greatness.[1]

After Olivier's death, Gielgud reflected, "He followed in the theatrical tradition of Kean and Irving. He respected tradition in the theatre, but he also took great delight in breaking tradition, which is what made him so unique. He was gifted, brilliant, and one of the great controversial figures of our time in theatre, which is a virtue and not a vice at all."[283]

Olivier said in 1963 that he believed he was born to be an actor,[284] but his colleague Peter Ustinov disagreed; he commented that although Olivier's great contemporaries were clearly predestined for the stage, "Larry could have been a notable ambassador, a considerable minister, a redoubtable cleric. At his worst, he would have acted the parts more ably than they are usually lived."[285] The director David Ayliff agreed that acting did not come instinctively to Olivier as it did to his great rivals. He observed, "Ralph was a natural actor, he couldn't stop being a perfect actor; Olivier did it through sheer hard work and determination."[286] The American actor William Redfield had a similar view:

Ironically enough, Laurence Olivier is less gifted than Marlon Brando. He is even less gifted than Richard Burton, Paul Scofield, Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud. But he is still the definitive actor of the twentieth century. Why? Because he wanted to be. His achievements are due to dedication, scholarship, practice, determination and courage. He is the bravest actor of our time.[287]

In comparing Olivier and the other leading actors of his generation, Ustinov wrote, "It is of course vain to talk of who is and who is not the greatest actor. There is simply no such thing as a greatest actor, or painter or composer".[288] Nonetheless, some colleagues, particularly film actors such as Spencer Tracy, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, came to regard Olivier as the finest of his peers.[289] Peter Hall, though acknowledging Olivier as the head of the theatrical profession,[290] thought Richardson the greater actor.[217] Others, such as the critic Michael Coveney, awarded the palm to Gielgud.[291] Olivier's claim to theatrical greatness lay not only in his acting, but as, in Hall's words, "the supreme man of the theatre of our time",[292] pioneering Britain's National Theatre.[210] As Bragg identified, "no one doubts that the National is perhaps his most enduring monument".[293]

Stage roles and filmography

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Gerard's father Henry Arnold Olivier (1826–1912) was a priest who had eight children, his other sons all achieving success in secular spheres: Sydney became Governor of Jamaica and later Secretary of State for India, Herbert was a successful portrait painter, and Henry (1850–1935) had a military career, ending as a colonel.[3]

- ↑ In a biography of Olivier Melvyn Bragg observes that all three of the great theatrical trinity of the century—Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud and Olivier—went through deeply religious phases when young.[11]

- ↑ Olivier had not been especially popular until then and noted in his diary at the time that he played "very well, to everyone's disgust".[16]

- ↑ Olivier said that he was surprised and moved that his father, who until then he had thought did not care about him, had devoted considerable thought to his son's future.[18]

- ↑ Olivier's biographers W. A. Darlington and Anthony Holden both suggest another reason: Fogerty's determination to recruit more male students, there being at the time only six boys to seventy girls enrolled at the school.[20]

- ↑ Gielgud and Olivier himself later considered that not being in the nearly two-year run of Journey's End[32] helped Olivier's career. Gielgud wrote in the 1970s, "Olivier made his name in three plays that failed with the public—Beau Geste, The Circle of Chalk with Anna May Wong, and The Rats of Norway by Keith Winter. In all three plays he got superb notices personally, so that in a curious way it made his career to be in failures."[33] Olivier said much the same to Bragg in the 1980s.[34]

- ↑ A German-language version was also filmed, in which Olivier did not appear.[36]

- ↑ The £60 salary in 1930 is approximately £3,300 in 2015.[38]

- ↑ Esmond was predominantly lesbian; this was socially unacceptable in her lifetime, and was rarely mentioned.[43]

- ↑ Their son, (Simon) Tarquin, was born in August 1936.[44]

- ↑ The biographer Cole Lesley wrote that Coward "invented a dog called Roger, unseen but who was always on stage with them when he and Larry had a scene together. Roger belonged to Noel but was madly attracted by Larry, especially to his private parts both before and behind, to which he invisibly did unmentionable things in full sight of the audience. 'Down, Roger,' Noel would whisper, or, 'Not in front of the vicar!' until in the end, as though this time the dog really had gone much too far, a shocked 'Roger!' was quite enough".[49]

- ↑ $1,000 in 1931 is approximately $15,500 in 2015.[51]

- ↑ The original casting applied from 18 October to 28 November 1935; the two leading men then switched roles for alternating periods of several weeks at a time during the run. For the last week, ending on 28 March 1936, Olivier was Mercutio and Gielgud Romeo.[59]

- ↑ The previous record was 161 performances, by Henry Irving and Ellen Terry in 1882.[59]

- ↑ Although most contemporary critics thought that Gielgud spoke the verse well and Olivier did not, Gielgud himself came to think they may have been wrong. He said in the 1980s, "He [Olivier] was much more natural than I in his speech, too natural I thought at the time, but now I think he was right and I was wrong and that it was time to say the lines the modem way. He was always so bold: and even if you disagreed, as I sometimes did, about his conception, you had to admire its execution, the energy and force with which he carried it through."[60]

- ↑ Olivier had received £500–£600 a week for his recent film work; at the Old Vic his weekly wage was £20.[64]

- ↑ Ivor Brown called Gielgud's performance "tremendous ... the best Hamlet of [my] experience."[67] James Agate wrote, "I have no hesitation whatsoever in saying that it is the high water-mark of English Shakespearean acting of our time."[68]

- ↑ Olivier never overtly acknowledged his affair with Ainley, although Ainley's letters to him are clear. Olivier's third wife, the actress Joan Plowright, expressed surprise at hearing the possibility, but commented, "If he did, so what?"[78] Later, there were also persistent rumours of an affair with the entertainer Danny Kaye,[79] although Coleman considers them to be unsubstantiated;[80] Plowright also dismisses the rumours.[81]

- ↑ $50,000 in 1939 is approximately $850,000 in 2015.[51]

- ↑ Robert Donat won the award that year for his performance in Goodbye, Mr. Chips.[94]

- ↑ Korda acted both as a cover for British Intelligence in the US, and as part of an unofficial propaganda machine to sway the still-neutral Americans.[105]

- ↑ Almost everyone in theatrical circles called Olivier "Larry", but Richardson invariably addressed him as "Laurence". In contrast to this striking formality, Richardson addressed Gielgud as "Johnny".[123]

- ↑ The sources generally refer to the two parts of Henry IV as a double bill, although as full-length plays they were given across two separate evenings.[129]

- ↑ The film also won Oscars for Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design, and was nominated for awards for Best Actress (Jean Simmons as Ophelia), Best Score and Olivier as Best Director.[143]

- ↑ Holden, noting that one of the failures was written and directed by Guthrie, comments that Olivier's willingness to stage it was an example of his magnanimous side.[155]

- ↑ Tynan wrote in The Observer, "As Lavinia, Vivien Leigh receives the news that she is about to be ravished on her husband's corpse with little more than the mild annoyance of one who would have preferred foam rubber".[182]

- ↑ The other two Jeans were Dorothy Tutin at the Royal Court, and Geraldine McEwan for part of the run at the Palace.[189] Plowright rejoined the cast when the production opened in New York in February 1958.[190]

- ↑ In 1955 Richardson, advised by Gielgud, had turned down the role of Estragon in Peter Hall's premiere of the English language version of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot and later reproached himself for missing the chance to be in "the greatest play of my generation".[193]

- ↑ Billington describes Olivier's attitude to Richardson and others as "most ungenerous".[1]

- ↑ Because of this additional commitment, Olivier had to drop his plan to direct Coward's Hay Fever.[219] The author took over the production with a cast, headed by Edith Evans, that Coward said could successfully have played the Albanian telephone directory.[220]

- ↑ With the exception of a walk-on role in a matinée performance of scenes from the play in 1926, with Thorndike as Portia.[230]

- ↑ Olivier was also offered an honorary degree from Yale University, but was unable to receive it.[262]

- ↑ For Richard III (1955) and Oh! What a Lovely War (1969).[264]

- ↑ For his appearances in screen versions of The Moon and Sixpence (1960), Long Day's Journey into Night (1973), Love Among the Ruins, Brideshead Revisited (1982) and King Lear (1984)[200]

- ↑ As Best Actor for Hamlet, Best Supporting Actor for Marathon Man and the Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievement.[200]

- ↑ The American film director William Wyler said that Olivier's performance in the film Carrie was "the truest and best portrayal on film of an American by an Englishman".[274]

- ↑ Billington cites one of the best known instances of Olivier's physicality: "a sense of daring [which] showed itself, physically, in such feats as his famous headlong deathfall off a 12-foot-high platform in Coriolanus (Olivier was 52 at the time)."[278]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Billington 2004.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 12.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 11.

- 1 2 Darlington 1968, p. 13.

- ↑ Beckett 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 14.

- ↑ Beckett 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Kiernan 1981, p. 12.

- ↑ Holden 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Denny 1985, p. 269.

- ↑ Bragg 1989, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tynan, Kenneth (Winter 1966). "The Actor: Tynan Interviews Olivier". The Tulane Drama Review (11.2): 71–101. (subscription required)

- ↑ Findlater 1971, p. 207; Beckett 2005, p. 9.

- ↑ Kiernan 1981, p. 20.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 26.

- ↑ Barker 1984, p. 15.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, p. 15.

- ↑ Bragg 1989, p. 38.

- 1 2 Holden 1988, p. 29.

- ↑ Darlington 1968, p. 1; Holden 1988, p. 29.

- ↑ Billington 2004; Munn 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 32.

- ↑ Beckett 2005, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Mortimer 1984, p. 61.

- ↑ Bragg 1989, p. 59.

- ↑ Jackson 2013, p. 67.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 455.

- ↑ Munn 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, p. 75.

- ↑ Coleman 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ "The London Stage: Beau Geste at His Majesty's". The Manchester Guardian. 1 February 1929. p. 14.

- ↑ Gaye 1967, p. 1533.

- ↑ Gielgud 1979, p. 219.

- ↑ Bragg 1989, p. 45.

- 1 2 Olivier 1994, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Tanitch 1985, p. 36.

- ↑ Coleman 2006, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Clark, Gregory. "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ↑ Bragg 1989, p. 65.

- ↑ Munn 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Coleman 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, p. 88.

- ↑ Garber 2013, p. 136; Beckett 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, p. 77.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, p. 89.

- ↑ Lesley 1976, p. 136.

- ↑ Lesley 1976, p. 137.

- ↑ Castle 1972, p. 115.

- ↑ Lesley 1976, p. 138.

- ↑ Morley 1974, p. 176.

- 1 2 "Consumer Price Index, 1913–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, p. 92.

- ↑ Olivier 1994, pp. 93–94; Munn 2007, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Richards 2014, p. 64.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 71.

- ↑ Billington 2004; Munn 2007, pp. 44–45; Richards 2010, p. 165.

- ↑ Darlington 1968, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Findlater 1971, p. 57.

- 1 2 "Mr Gielgud's Plans". The Times. 10 March 1936. p. 14.

- ↑ Bragg 1989, p. 60.

- ↑ Morley 2001, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Miller 1995, p. 60.

- ↑ Gilbert 2009, p. 16.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 114.

- ↑ Miller 1995, p. 36.

- ↑ Holden 1988, p. 115.

- ↑ Brown, Ivor (29 May 1930). "Mr John Gielgud's Hamlet". The Manchester Guardian. p. 6.

- ↑ Croall 2000, p. 129.

- ↑ Brown, Ivor (10 January 1937). "Hamlet in Full". The Observer. p. 15.