Lauren Bacall

| Lauren Bacall | |

|---|---|

|

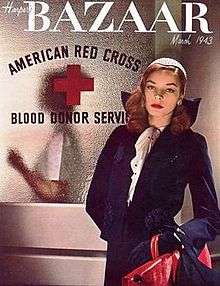

Bacall in March 1945 | |

| Born |

Betty Joan Perske September 16, 1924 The Bronx, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

August 12, 2014 (aged 89) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Resting place |

Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Actress, model |

| Years active | 1942–2014 |

| Height | 5 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1.74 m)[1] |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 3, including Sam Robards |

| Signature | |

| |

Lauren Bacall (/ˌlɔːrən bəˈkɔːl/, born Betty Joan Perske; September 16, 1924 – August 12, 2014) was an American actress and singer known for her distinctive voice and sultry looks. She was named the 20th greatest female star of Classic Hollywood cinema by the American Film Institute, and received an Academy Honorary Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2009, "in recognition of her central place in the Golden Age of motion pictures."[2]

Bacall began her career as a model,[3] before making her debut as a leading lady with Humphrey Bogart in the film To Have and Have Not in 1944. She continued in the film noir genre with appearances with Bogart in The Big Sleep (1946), Dark Passage (1947), and Key Largo (1948), and starred in the romantic comedies How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) with Marilyn Monroe and Designing Woman (1957) with Gregory Peck. She co-starred with John Wayne in his final film, The Shootist (1976). Bacall also worked on Broadway in musicals, earning Tony Awards for Applause (1970) and Woman of the Year (1981). Her performance in The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996) earned her a Golden Globe Award and an Academy Award nomination.

A month before her 90th birthday, Bacall died in New York City after a stroke.

Early life

Bacall was born Betty Joan Perske on September 16, 1924, in The Bronx, New York,[4][5] the only child of Natalie (née Weinstein; 1901–1977), a secretary who later legally changed her surname to Bacall, and William Perske, who worked in sales.[6] Both her parents were Jewish. According to Bacall, her mother emigrated from the Kingdom of Romania through Ellis Island, and her father was born in New Jersey to parents who were born in Valozhyn, a significant center of Jewish life in present-day Belarus, then in the Russian Empire.[7]

Soon after her birth, Bacall's family moved to Brooklyn's Ocean Parkway.[7][8] She was educated with the financial support of her wealthy uncles at a private boarding school founded by philanthropist Eugene Heitler Lehman, named The Highland Manor Boarding School for Girls,[9] in Tarrytown, New York, and at Julia Richman High School in Manhattan.[10]

Through her father, she was a relative of Shimon Peres (born Szymon Perski), the ninth President of Israel.[11][12][13] Peres has stated, "In 1952 or 1953 I came to New York... Lauren Bacall called me, said that she wanted to meet, and we did. We sat and talked about where our families came from, and discovered that we were from the same family... but I'm not exactly sure what our relation is... It was she who later said that she was my cousin, I didn't say that".[11] Her parents divorced when she was five; she later took the Romanian form of her mother's last name, Bacall.[14] She no longer saw her father and formed a very close bond with her mother, who remarried Lee Goldberg and came to live in California after Bacall became a movie star.[15][16]

Early career and modeling

In 1941, Bacall took lessons at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York, where she was classmates with Kirk Douglas,[17] while working as a theatre usher at the St. James Theatre and fashion model.[4]

She made her acting debut on Broadway in 1942, at age 17, as a walk-on in Johnny 2 X 4. By then, she lived with her mother on Bank Street, Greenwich Village, and in 1942 she was crowned Miss Greenwich Village.[18]

As a teenage fashion model she appeared on the cover of Harper's Bazaar, as well as in magazines such as Vogue.[16] She was noted for her "cat-like grace, tawny blonde hair and blue-green eyes".[19]

Though Diana Vreeland is often credited with discovering Bacall for Harper's Bazaar, it was in fact Nicolas de Gunzburg who introduced the 18-year-old to Vreeland. He had first met Bacall at Tony's, a club in the East 50s. De Gunzburg suggested that Bacall stop by his Bazaar office the next day. He then turned over his find to Vreeland, who arranged for Louise Dahl-Wolfe to shoot Bacall in Kodachrome for the March 1943 cover.[20]

The Harper's Bazaar cover caught the attention of Hollywood producer and director Howard Hawks' wife Slim,[21] who urged Hawks to have Bacall take a screen test for To Have and Have Not. Hawks asked his secretary to find out more about her, but the secretary misunderstood and sent Bacall a ticket to come to Hollywood for the audition.[22]

Hollywood

After meeting Bacall in Hollywood, Hawks immediately signed her to a seven-year contract with a weekly salary of $100, and personally began to manage her career. He changed her first name to Lauren, and she chose "Bacall" (a variant of her mother's maiden name) as her screen surname. Slim Hawks also took Bacall under her wing,[23] dressing Bacall stylishly and guiding her in matters of elegance, manners and taste. At Hawks' suggestion, Bacall was also trained to make her voice lower and deeper instead of her normal high-pitched, nasal voice. Hawks had her, under the tutelage of a voice coach, lower the pitch of her voice.[24] As part of her training, she was required to shout verses of Shakespeare for hours every day.[23][25] Her height, at 5 feet 8½ inches,[1] unusual among young actresses in the 1940s and 1950s, also helped her stand out. Her voice was characterized as a "smoky, sexual growl" by most critics,[1] and a "throaty purr".[24]

During her screen tests for To Have and Have Not (1944), Bacall was so nervous that, to minimize her quivering, she pressed her chin against her chest, faced the camera and tilted her eyes upward.[26] This effect, which came to be known as "The Look", became another Bacall trademark along with her sultry voice.[27]

Bacall's character in the film used Slim Hawks' nickname "Slim", and Bogart used Howard Hawks' nickname "Steve". The on-set chemistry between the two was immediate according to Bacall.[7] She and Bogart (who was married at the time to Mayo Methot) began a romantic relationship several weeks into shooting.[21]

Bacall's role in the script was originally much smaller, but during filming her part was revised multiple times to extend it into the lead part that it became in the released film.[28] Once released, To Have and Have Not catapulted Bacall into instant stardom, and her performance became the cornerstone of her star image, the impact of which extended into popular culture at large, even influencing fashion,[29] as well as filmmakers and other actors.[28]

Warner Bros. launched an extensive marketing campaign to promote the picture and to establish Bacall as a movie star. As part of the public relations push, Bacall made a visit to the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., on February 10, 1945. It was there that Bacall's press agent, chief of publicity at Warner Bros. Charlie Enfield, asked the 20-year-old Bacall to sit on the piano while U.S. Vice President Harry S. Truman played.[30][31]

After To Have and Have Not, Bacall was seen opposite Charles Boyer in Confidential Agent (1945), which was poorly received by critics. By her own estimation, it could have caused considerable damage to her career, had her performance as the mysterious, acid-tongued Vivian Rutledge in Hawks's film noir The Big Sleep (1946), co-starring Bogart, not provided a quick career resurgence.[32]

The Big Sleep laid the foundation for her status as an icon of film noir. She would be strongly associated with the genre for the rest of her career,[33][34][35] and would often be cast as variations of the independent and sultry femme fatale character of Vivian she played in the movie. As described by film scholar Joe McElhaney, "Vivian displays an almost total command of movement and gesture. She never crawls."[36]

Bacall was cast with Bogart in two more films. In Dark Passage (1947), another film noir, she played an enigmatic San Francisco artist. "Miss Bacall -- generates quite a lot of pressure as a sharp-eyed, knows-what-she-wants girl", wrote Bosley Crowther of The New York Times of her performance.[37] And, in 1948, she was in John Huston's melodramatic suspense film Key Largo with Bogart and Edward G. Robinson. In the film, according to film critic Jessica Kiang, "Bacall brings an edge of ambivalence and independence to the role that makes her character much more interesting than was written."[38]

1950s

Bacall turned down scripts she did not find interesting, and thereby earned a reputation for being difficult. Despite this, she further solidified her star status in the 1950s by appearing as the leading lady in a string of films that won favorable reviews.

Bacall was cast opposite Gary Cooper in Bright Leaf (1950). In the same year, she played a two-faced femme fatale in Young Man with a Horn (1950), a jazz musical co-starring Kirk Douglas, Doris Day, and Hoagy Carmichael.

During 1951–1952, Bacall co-starred with Bogart in the syndicated action-adventure radio series Bold Venture.[39]

In 1953 she starred in the CinemaScope comedy How to Marry a Millionaire, a runaway hit among critics and at the box office.[40] Directed by Jean Negulesco and co-starring Marilyn Monroe and Betty Grable, Bacall got positive notices for her turn as the witty gold-digger, Schatze Page.[41] "First honors in spreading mirth go to Miss Bacall", wrote Alton Cook in The New York World-Telegram & Sun. "The most intelligent and predatory of the trio, she takes complete control of every scene with her acid delivery of viciously witty lines."[42]

After the success of How to Marry a Millionaire, she was offered, but declined, with Bogart's support, the coveted invitation from Grauman's Chinese Theatre to press her hand- and footprints in the theatre's cemented forecourt. But she felt at the time that "anyone with a picture opening could be represented there, standards had been so lowered." She didn't feel she had yet achieved the status of a major star, and was thereby unworthy of the honor:[43] "I want to feel I've earned my place with the best my business has produced."[7]:236

At the time, Bacall was still under contract to 20th Century Fox.[42] Following How to Marry a Millionaire, she appeared in yet another CinemaScope comedy directed by Jean Negulesco, Woman's World (1954), which failed to match its predecessor's success at the box office.[44][45]

In 1955 a television version of Bogart's breakthrough film, The Petrified Forest, was performed as a live installment of Producers' Showcase, a weekly dramatic anthology, featuring Bogart as Duke Mantee, Henry Fonda as Alan, and Bacall as Gabrielle, the part originally played in the 1936 movie by Bette Davis. Bogart had originally played the part on Broadway with the subsequent movie's star Leslie Howard, who had secured a film career for Bogart by insisting that Warner Bros. cast him in the movie instead of Edward G. Robinson; Bogart and Bacall named their daughter "Leslie Howard Bogart" in gratitude.[46]

In the late 1990s, Bacall donated the only known kinescope of the 1955 performance to The Museum Of Television & Radio (now the Paley Center for Media), where it remains archived for viewing in New York City and Los Angeles.[47]

In 1955 Bacall starred in two feature films, The Cobweb and Blood Alley. Directed by Vincente Minnelli, The Cobweb takes place at a mental institution in which Bacall's character works as a therapist. It was her second collaboration with Charles Boyer and also starred Richard Widmark and Lillian Gish. "In the only two really sympathetic roles, Mr. Widmark is excellent and Miss Bacall shrewdly underplays", wrote The New York Times.[48]

Many film scholars consider Written on the Wind, directed by Douglas Sirk in 1956, to be a landmark work in the melodrama genre.[49] Appearing with Rock Hudson, Dorothy Malone and Robert Stack, Bacall played a career woman whose life is unexpectedly turned around by a family of oil magnates. Bacall wrote in her autobiography that she did not think much of the role, but reviews were favorable. Wrote Variety, "Bacall registers strongly as a sensible girl swept into the madness of the oil family".[50]

While struggling at home with Bogart's battle with esophageal cancer, Bacall starred with Gregory Peck in Designing Woman to solid reviews.[51] The musical comedy was her second feature with director Vincente Minnelli and was released in New York on May 16, 1957, four months after Bogart's death on January 14.[7]

Bacall appeared in two more films in the 1950s: the Jean Negulesco-directed melodrama The Gift of Love (1958), which co-starred Robert Stack; and the adventure film North West Frontier (1959), which was a box office hit.[52]

1960s and 1970s

Bacall's movie career waned in the 1960s, and she was seen in only a handful of films. She starred on Broadway in Goodbye, Charlie in 1959, and went on to have a successful on-stage career in Cactus Flower (1965), Applause (1970), and Woman of the Year (1981). She won Tony Awards for her performances in the latter two.[53]

Applause was a musical version of the film All About Eve, in which Bette Davis had starred as stage diva Margo Channing. According to Bacall's autobiography, she and a girlfriend won an opportunity in 1940 to meet her idol Bette Davis at Davis' hotel.[7] Years later, Davis visited Bacall backstage to congratulate her on her performance in Applause. Davis told Bacall, "You're the only one who could have played the part."[54]

The few films Bacall made during this period were all-star vehicles such as Sex and the Single Girl (1964) with Henry Fonda, Tony Curtis, and Natalie Wood; Harper (1966) with Paul Newman, Shelley Winters, Julie Harris, Robert Wagner, and Janet Leigh; and Murder on the Orient Express (1974), with Ingrid Bergman, Albert Finney, Vanessa Redgrave, Martin Balsam, and Sean Connery.[46]

In 1964 she appeared in two episodes of Craig Stevens's Mr. Broadway: first in "Take a Walk Through a Cemetery", with then husband, Jason Robards, Jr.,[46] and later as Barbara Lake in the episode "Something to Sing About", co-starring future co-star Balsam.[55]

For her work in the Chicago theatre, Bacall won the Sarah Siddons Award in 1972, and again in 1984.

In 1976 she co-starred with John Wayne in his last picture, The Shootist. The two became friends, despite significant political differences between them.[7] They had also worked together in Blood Alley (1955).[56]

Later career

During the 1980s, Bacall appeared in the poorly received star vehicle The Fan (1981). She received favorable reception, Vincent Canby writing her character of Sally Ross as "the most fully drawn, the most engaging and the sexiest character that Miss Bacall has played on the screen since her early great days with Humphrey Bogart and Howard Hawks 35 years ago"[57] and Variety observing, "Lauren Bacall makes the film [from a novel by Bob Randall] work with a solid performance as a stage star pursued by a pyschotic fan whose adoration turns to hatred. To be sure, the part doesn’t test the broadest range of Bacall’s abilities, but she and director Edward Bianchi achieve the essential element: they make the audience care what happens to her."[58]

Bacall also was featured in Robert Altman's Health (1980) and Michael Winner's Appointment with Death (1988). In 1990, she had a small role in Misery, which starred Kathy Bates and James Caan.

In 1997, Bacall was nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award for her role in The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996), her first nomination after a career span of more than fifty years.[59] Bacall had already won a Golden Globe and was widely expected to win the Oscar, but lost in an upset to Juliette Binoche for The English Patient.[60]

Bacall received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1997,[61] and in 1999, she was voted one of the 25 most significant female movie stars in history by the American Film Institute. Her movie career saw something of a renaissance, and she attracted respectful notices for her performances in high-profile projects such as Dogville (2003), Birth (2004), both with Nicole Kidman, and in Howl's Moving Castle (2004), as the Witch of the Waste. She was a leading actor in Paul Schrader's The Walker (2007).[62]

In 1999, Bacall starred on Broadway in a revival of Noël Coward's Waiting in the Wings.[63]

Her commercial ventures in the 2000s included being a spokesperson for the Tuesday Morning discount chain (commercials showed her in a limousine waiting for the store to open at the beginning of one of their sales events), and producing a jewelry line with the Weinman Brothers company. She had been a celebrity spokesperson for High Point coffee and Fancy Feast cat food. In March 2006, Bacall was seen at the 78th Annual Academy Awards introducing a film montage dedicated to film noir. She made a cameo appearance as herself on The Sopranos, in the April 2006 episode, "Luxury Lounge", during which she was mugged by Chris Moltisanti (played by Michael Imperioli).[64]

In September 2006, Bacall was awarded the first Katharine Hepburn Medal, which recognizes "women whose lives, work and contributions embody the intelligence, drive and independence of the four-time-Oscar-winning actress", by Bryn Mawr College's Katharine Houghton Hepburn Center.[65] She gave an address at the memorial service of Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. at the Reform Club in London in June 2007.[66] She finished her role in The Forger in 2009.[67]

Bacall was selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to receive an Honorary Academy Award. The award was presented at the inaugural Governors Awards on November 14, 2009.[68]

In July 2013, Bacall expressed interest in taking the starring role in the film Trouble Is My Business.[69] In November, she joined the English dub voice cast for StudioCanal's animated film Ernest & Celestine.[70] Her final role was in 2014: a guest vocal appearance in the twelfth season Family Guy episode "Mom's the Word".[71]

Personal life

Relationships and family

On May 21, 1945, Bacall married actor Humphrey Bogart, 25 years her senior. Their wedding and honeymoon took place at Malabar Farm, Lucas, Ohio, the country home of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louis Bromfield, a close friend of Bogart.[72] The wedding was held in the Big House.[73]

They remained married until Bogart's death from esophageal cancer in 1957. Pressed by interviewer Michael Parkinson to talk about her marriage to Bogart, and asked about her notable reluctance to do so, she replied that "being a widow is not a profession".[74] During the filming of The African Queen (1951), Bacall and Bogart became friends with Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. She began to mix in non-acting circles, becoming friends with the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and the journalist Alistair Cooke. In 1952, she gave campaign speeches for Democratic Presidential contender Adlai Stevenson. Along with other Hollywood figures, Bacall was a staunch opponent of McCarthyism.[75][76]

Shortly after Bogart's death in 1957, Bacall had a relationship with singer and actor Frank Sinatra. During an interview with Turner Classic Movies's Robert Osborne, Bacall stated that she had ended the romance, but, in her autobiography, she wrote that Sinatra ended the relationship abruptly after becoming angry that the story of his marriage proposal to Bacall had reached the press. When Bacall was out with her friend Irving Paul Lazar, they encountered the gossip columnist Louella Parsons, to whom Lazar revealed the details of the proposal.[77]

Bacall later met actor Jason Robards. Their marriage was originally scheduled to take place in Vienna, Austria, on June 16, 1961;[78] however, the plans were shelved after Austrian authorities refused to grant the pair a marriage license.[79] They were refused a marriage also in Las Vegas, Nevada.[80] On July 4, 1961, the couple drove all the way to Ensenada, Mexico, where they wed.[80][81] The couple divorced in 1969. According to Bacall's autobiography, she divorced Robards mainly because of his alcoholism.[82][83]

Bacall had two children with Bogart and one with Robards. Son Stephen Humphrey Bogart (born January 6, 1949) is a news producer, documentary film maker, and author named after Bogart's character in To Have and Have Not.[72] Her daughter Leslie Howard Bogart (born August 23, 1952) is named for actor Leslie Howard. A nurse and yoga instructor, she is married to Erich Schiffmann.[72] In his 1995 memoir, Stephen Bogart wrote, "My mother was a lapsed Jew, and my father was a lapsed Episcopalian," and that he and his sister were raised Episcopalian "because my mother felt that would make life easier for Leslie and me during those post-World War II years".[72] Sam Robards (born December 16, 1961), Bacall's son with Robards, is an actor.[84]

Bacall wrote two autobiographies, Lauren Bacall By Myself (1978) and Now (1994).[85][86] In 2006, the first volume of Lauren Bacall By Myself was reprinted as By Myself and Then Some with an extra chapter.[87]

Political views

Bacall was a staunch liberal Democrat, and proclaimed her political views on numerous occasions.[72] Bacall and Bogart were among about 80 Hollywood personalities to send a telegram protesting the House Un-American Activities Committee's investigations of Americans suspected of Communism. The telegram said that investigating individuals' political beliefs violated the basic principles of American democracy.[72] In October 1947, Bacall and Bogart traveled to Washington, D.C., along with a number of other Hollywood stars in a group that called itself the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA), which also included Danny Kaye, John Garfield, Gene Kelly, John Huston, Ira Gershwin and Jane Wyatt.[72]

She appeared alongside Humphrey Bogart in a photograph printed at the end of an article he wrote, titled "I'm No Communist", in the May 1948 edition of Photoplay magazine,[88] written to counteract negative publicity resulting from his appearance before the House Committee. Bogart and Bacall distanced themselves from the Hollywood Ten and said: "We're about as much in favor of Communism as J. Edgar Hoover."[89][90]

Bacall campaigned for Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson in the 1952 presidential election, accompanying him on motorcades along with Bogart, and flying east to help in the final laps of Stevenson's campaign in New York and Chicago.[72] She also campaigned for Robert Kennedy in his 1964 run for the U.S. Senate.[91]

In a 2005 interview with Larry King, Bacall described herself as "anti-Republican... A liberal. The L-word." She added that "being a liberal is the best thing on earth you can be. You are welcoming to everyone when you're a liberal. You do not have a small mind."[92]

Death

Lauren Bacall died on August 12, 2014, at her longtime apartment in The Dakota, the Upper West Side building overlooking Central Park in Manhattan. She was 89, five weeks short of her 90th birthday.[72] According to her grandson Jamie Bogart, the actress died after suffering a massive stroke.[3] She was confirmed dead at New York–Presbyterian Hospital.[93][94] By some accounts she was cremated and her ashes spread over Martha’s Vineyard.[95]

Bacall had an estimated $26.6 million estate. In her will she left $10,000 to her youngest son, Sam Robards, to take care of her dog, Sophie. Bacall also left money to two of her employees, Ilsa Hernandez and Maria Santos; Hernandez received $15,000 while Santos received $20,000. Bacall left $250,000 each to her youngest grandsons, the sons of Sam Robards for college, and the bulk of her estate was divided among her three children: Leslie Bogart, Stephen Humphrey Bogart, and Sam Robards.[96][97] She owned artworks by a number of artists, including John James Audubon, Max Ernst, David Hockney, Henry Moore and Jim Dine.[98]

In a 1996 interview Bacall, reflecting on her life, told the interviewer that she had been lucky: "I had one great marriage, I have three great children and four grandchildren. I am still alive. I still can function. I still can work," adding, "You just learn to cope with whatever you have to cope with. I spent my childhood in New York, riding on subways and buses. And you know what you learn if you're a New Yorker? The world doesn't owe you a damn thing."[72][99]

Filmography

Radio appearances

| Year | Program | Episode/source |

|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Lux Radio Theatre | To Have and Have Not[100] |

Books

- Lauren Bacall by Myself (1978)

- Now (1994)

- By Myself and Then Some (2005)

Awards and nominations

- 1967 Hasty Pudding Woman of the Year

- 1970 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical, Applause[101]

- 1972 Sarah Siddons Award Actress of the Year

- 1980 National Book Award in the one-year category: Autobiography[102][lower-alpha 1]

- 1981 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical, Woman of the Year[103]

- 1984 Sarah Siddons Award Actress of the Year

- 1990 George Eastman Award[104]

- 1992 Donostia Award (Honorary)

- 1993 Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award[105]

- 1994 National Board of Review Award for Best Cast, Prêt-à-Porter: Ready to Wear

- 1996 Honorary César

- 1997 Berlin International Film Festival, Berlinale Camera[106]

- 1997 Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Supporting Role, The Mirror Has Two Faces[107]

- 1997 Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture, The Mirror Has Two Faces[105]

- 1997 San Diego Film Critics Society Award for Best Supporting Actress, The Mirror Has Two Faces

- 1997 Kennedy Center Honors

- 2000 Stockholm International Film Festival Lifetime Achievement Award

- 2007 Norwegian International Film Festival Lifetime Achievement Award

- 2009 Academy Honorary Award in recognition of her central place in the golden age of motion pictures.[2]

Nominations

- 1977 BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, The Shootist[108]

- 1980 Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series, The Rockford Files

- 1997 BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, The Mirror Has Two Faces[108]

- 1997 Academy Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, The Mirror Has Two Faces[59]

In 1960, Bacall received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1724 Vine Street for her contributions to the motion pictures industry.[109] . In 1997, a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs, California, Walk of Stars was dedicated to her.[110] In 1998, Bacall was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.[111]

In popular culture

Film

- The 1980 television film, Bogie, directed by Vincent Sherman and based on a book by Joe Hyams, tells the story of Bogart meeting Bacall while making To Have and Have Not in 1943, and beginning the affair with her that led to the dissolution of Bogart's marriage to Mayo Methot.[112] Bacall is portrayed by Kathryn Harrold in the film, Kevin O'Connor plays Bogart, and Methot is played by Ann Wedgeworth.[113]

Animation

- Bacall and Bogart are parodied in the Warner Brothers Merrie Melodies shorts Bacall to Arms (1946).[114] and Slick Hare (1947).

Music

- Bacall and Bogart are referenced in Bertie Higgins' song "Key Largo" (1981).[115]

- Bacall is referenced in The Clash's song "Car Jamming" (1982).[115]

- Bacall and Bogart are referenced in Suzanne Vega's song "Freeze Tag" (1985).[115]

- She is referenced in "Vogue" the 1990 Madonna song. Bacall was the last to die of the mentioned celebrities.[115]

- She is the subject of the song, "Just Like Lauren Bacall" (2008), written by Kevin Roth.[115]

- She is referenced in the song, "You, Jane" (2012) by The Wedding Present.

Books

- Bacall and her Manhattan apartment are featured in The Dakota Scrapbook (2014), a photo-journalism volume on the history of the Dakota apartment building in New York City, and its famous residents over the years.[116][117]

Marshall Islands namesake

- The town of Laura—on the island of Majuro in the Marshall Islands—is one of several island towns code-named after famous pinups by WWII U.S. forces.[118]

See also

- Bogart and Bacall

- Bogart–Bacall syndrome

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with Hollywood Walk of Fame motion picture stars

Notes

- ↑ This was the 1980 award for hardcover Autobiography. From 1980 to 1983 in National Book Award history there were dual hardcover and paperback awards in most categories, and multiple nonfiction subcategories. Most of the paperback award-winners were reprints, including the 1980 Autobiography.

References

- 1 2 3 Betsy Sharkey. "Lauren Bacall's voice resonated with women". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- 1 2 "82nd Academy Award Winners". Oscars. 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- 1 2 Ford, Dana (August 12, 2014). "Famed actress Lauren Bacall dies at 89". CNN. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- 1 2 "Lauren Bacall Fast Facts". CNN Library. August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Tyrnauer, Matt (March 10, 2011). "To Have and Have Not". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ↑ Lauren Bacall profile, Film Reference.com; retrieved July 9, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bacall, Lauren. By Myself and Then Some, HarperCollins, New York, 2005. ISBN 0-06-075535-0

- ↑ Fahim, Kareem (October 10, 2008). "A Tree-Lined Boulevard That's a Park and a Living Room". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2014- referencing "By Myself and Then Some."

- ↑ Pike, Helen-Chantal (February 12, 2007). West Long Branch Revisited. Images of America. Arcadia Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0738549033.

- ↑ "Sultry, sophisticated and sassy, screen siren Bacall dies at 89". Irish Independent. August 14, 2014.

- 1 2 Anderman, Nirit (August 13, 2014). "Shimon Peres remembers 'very strong, very beautiful' relative Lauren Bacall". Haaretz. Tel Aviv.

- ↑ Lazaroff, Tovah (November 10, 2005). "Peres: Not such a bad record after all". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ↑ Weiner, Eric (June 13, 2007). "Shimon Peres Wears Hats of Peacemaker, Schemer". NPR. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey (April 18, 1997). Bogart: A Life in Hollywood. Houghton Mifflin. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-395-77399-4.

- ↑ Cantrell, Susan (July 19, 2009). "Lauren Bacall on Life, Acting, and Bogie". Carmel. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- 1 2 Wickware, Francis Sill (May 7, 1945). "Profile of Lauren Bacall". LIFE. 18: 100–106. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ↑ Thomas, Tony (1991). The Films of Kirk Douglas. New York: Citadel Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0806512174.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall Biography & Filmography". Matinee Classics. 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall". LIFE. 24 (3): 43. January 19, 1948.

- ↑ Collins, Amy Fine (September 2014). "A Taste for Living". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- 1 2 Thomson, David (September 11, 2004). "Lauren Bacall: The souring of a Hollywood legend". The Independent. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Bogdanovich, Peter (March 11, 1997). Who the Devil Made It. Knopf. p. 327. ISBN 978-0679447061. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- 1 2 Sperber, Ann M.; Lax, Eric (April 1997). Bogart. New York: Morrow. p. 246. ISBN 978-0688075392. Retrieved January 2, 2015. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Brody, Richard (August 13, 2014). "The Shadows of Lauren Bacall". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Hourican, Emily (August 17, 2014). "Lauren Bacall: A Panther in Her Overall Family Tree". Irish Independent. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ↑ Cope, Rebecca (August 13, 2014). "Lauren Bacall's Life in Pictures". Harpers Bazaar. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- 1 2 Dargis, Manohla (August 13, 2014). "That Voice, and the Woman Attached". The New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Style in film: Lauren Bacall in 'To Have and Have Not'". Classiq.me. June 5, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Peretti, Burton (September 17, 2012). The Leading Man: Hollywood and the Presidential Image. Rutgers University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8135-5405-1.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall sits atop a piano while Vice President Harry S. Truman plays at the National Press Club Canteen". Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum. February 10, 1945. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Bacall, Lauren (2005). By Myself and Then Some. Headline Book Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 0-7553-1351-8.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall: Sultry film-noir legend who taught Humphrey Bogart how to whistle and starred with Monroe and Grable". The Independent.co.uk. The Independent. 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall dead: Legendary Hollywood film noir actress dies aged 89". Metro.co.uk. Metro. August 13, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Beauty and brawn: Lauren Bacall's noir feminine legacy". The Conversation. The Coversation. August 13, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall: The Walk". The Cine-Files.com. The Cine-Files. Spring 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Dark Passage". The New York Times. 1947. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ "The Essentials: Lauren Bacall's 6 Best Performances". Indiewire. 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Dunning, John (May 7, 1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Oxford University Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ↑ Vogel, Michelle (April 24, 2014). Marilyn Monroe: Her Films, Her Life. McFarland. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7864-7086-0.

- ↑ Movie Reviews: "How to Marry a Millionaire", Rotten Tomatoes.com; retrieved August 13, 2014.

- 1 2 Quirk, Laurence J. (1986). Lauren Bacall: Her Films and Career. Citadel Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-8065-0935-X.

- ↑ Endres, Stacey. Hollywood's Chinese Theatre: The Hand and Footprints of the Stars, Pomegranate Press (1992) e-book

- ↑ Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History, Scarecrow Press, 1989 p225

- ↑ 'The Top Box-Office Hits of 1954', Variety Weekly, January 5, 1955

- 1 2 3 Lauren Bacall - IMDb Retrieved August 13, 2015

- ↑ "Broadcast Museum Seeks TV's Self-History". The New York Times. January 25, 1987. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Review: The Cobweb". The New York Times. August 6, 1955. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Filmsite Movie Review: Written on the Wind (1956)". Film Site. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Review: Written on the Wind". Variety. December 31, 1955. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Designing Woman profile, Rotten Tomatoes.com; accessed August 14, 2014.

- ↑ Four British Films in 'Top 6': Boulting Comedy Heads Box Office List, The Guardian (1959–2003), London (UK), December 11, 1959: p. 4.

- ↑ Lauren Bacall at the Internet Broadway Database

- ↑ Chandler, Charlotte (December 9, 2008). The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis A Personal Biography. Simon and Schuster. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-84739-698-3.

- ↑ "Next Saturday". The Beaver County Times. Google News Archive. December 12, 1964. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Richard Natale (August 12, 2014). "Lauren Bacall, Star of Hollywood's Golden Age, Dies at 89". Variety. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (May 22, 1981). "FILM: 'FAN,' A LAUREN BACALL THRILLER". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Fan". Variety. December 31, 1981.

- 1 2 "69th Academy Award Winners". Oscars. 1996. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Soares, Andre. "Lauren Bacall vs. Juliette Binoche: The 1997 Academy Awards". Alt Film Guide. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ Lyman, Rick (December 8, 1997). "A Wind of Gratitude Blows Through the Performing Arts". New York Times. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ Adam Bernstein (August 12, 2014). "Lauren Bacall, sultry star of film and Broadway, dies at 89". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Waiting in the Wings Play". Playbill Vault. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ↑ Kois, Dan (August 12, 2014). "Lauren Bacall was game for anything, even getting punched out on 'The Sopranos'". Slate. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Katharine Houghton Hepburn Center". Bryn Mawr College. February 7, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Jenkins, Simon (June 28, 2007). "Our trigger-happy rulers should have been sent on a crash course in history". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ McNary, Dave (February 1, 2009). "Hutcherson rounds out 'Carmel' cast". Variety. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Bacall, Calley, Corman and Willis to Receive Academy's Governors Awards", Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences (press release), September 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Trouble Is My Business", juntoboxfilms.com, July 2013.

- ↑ Keslassy, Elsa (November 8, 2013). "Ernest & Celestine: Toon Taps Lauren Bacall, Paul Giamatti, William H. Macy (exclusive)". Variety. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Breaking News - Tony Award Winner Lauren Bacall Dies at 89". Broadway World. August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Lauren Bacall Dies at 89; in a Bygone Hollywood, She Purred Every Word". New York Times. August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Malabar Farm State Park Photo". 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ Lauren Bacall interview on Parkinson. YouTube, August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Levy, Patricia (2006). From Television to the Berlin Wall. Raintree. pp. 27–. ISBN 9781410917874. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Kuhn, Annette; Radstone, Susannah (1990). The Women's Companion to International Film. University of California Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 9780520088795. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Bacall, Lauren (August 18, 2014). "My volcanic affair with Sinatra: Red-hot passion one moment. Cutting her dead the next.". The Daily Mail. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall, Jason Robards to wed". The Evening Independent. Google News Archive. June 15, 1961. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Vienna foils wedding plans of Lauren Bacall, Robards". The Tuscaloosa News. Google News Archive. Associated Press. June 16, 1951. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- 1 2 "Lauren Bacall, Jason Robards wed in Mexico". The Deseret News. Google News Archive. United Press International. July 5, 1961. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Hickey, Neil (August 19, 1961). "Her Kind of Boy". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Google News Archive. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Lauren Bacall (October 31, 2006). By Myself and Then Some (Harper paperback ed.). New York: HarperCollins. p. 377. ISBN 0061127914.

- ↑ News Corp Australia (August 13, 2014). "Lauren Bacall dead at 89". News Corp Australia. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Robards - IMDb Retrieved August 22, 2015

- ↑ Lauren Bacall (October 12, 1985). Lauren Bacall: By Myself. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0345333217.

- ↑ Lauren Bacall (November 29, 1995). Now (1st Ballantine Books ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0345402324.

- ↑ Lauren Bacall (October 31, 2006). By Myself and Then Some (Harper paperback ed.). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0061127914.

- ↑ Humphrey Bogart. "Photoplay, March 1948". Google Docs. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

I'm no communist

- ↑ Gordon, Lois G.; Gordon, Alan (1987). American Chronicle: Six Decades in American Life, 1920-1980. Atheneum. p. 267. ISBN 9780689118999. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Dr. Paul Kengor (August 15, 2014). "Bogie and Bacall and Hollywood's Communists". Human Events. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Tomasky, Michael (August 13, 2014). "Lauren Bacall was deeply liberal and deeply anti-communist". The Daily Beast. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ "CNN LARRY KING LIVE: Interview with Lauren Bacall". CNN. May 6, 2005. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Mike Barnes; Duane Byrge (August 12, 2014). "Lauren Bacall, Hollywood's Icon of Cool, Dies at 89". Yahoo!. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Legendary Actress Lauren Bacall Dies at 89". New York Telegraph. August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2. McFarland & Company (2016) ISBN 0786479922

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall leaves $10,000 for her beloved dog in will". Fox News. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Mehdi Khomein Abadi (August 24, 2014). "Lauren Bacall Leaves Money To Grandchildren, Employees and Beloved Dog". Air Herald. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Carol Vogel (October 9, 2014), What Bacall Loved New York Times.

- ↑ "BBC - The Late Show - Face to Face: Lauren Bacall", Interview with Jeremy Isaacs, BBC, March 20, 1995

- ↑ "Bacall & Bogart Lux Theatre Stars". Harrisburg Telegraph. October 12, 1946. p. 17. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "1970 – 24th ANNUAL TONY AWARDS®". IBM Corp., Tony Award Productions. April 19, 1970. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "National Book Awards – 1980", nationalbook.org; retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ↑ "1981 – 35th ANNUAL TONY AWARDS®". IBM Corp., Tony Award Productions. June 7, 1981. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Lauren Bacall Receives George Eastman Award". The New York Times. The New York Times. November 10, 1990. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- 1 2 "Lauren Bacall 1 Nomination | 1 Win | 1 Special Award". Golden Globe Awards; Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Berlinale: 1997 Prize Winners". Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ↑ "The 3rd Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". SAG-AFTRA. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- 1 2 "Lauren Bacall Search Results". BAFTAs. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Hollywood Walk of Fame - Lauren Bacall". walkoffame.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. February 8, 1960. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "LISTED BY DATE DEDICATED" (PDF). Palm Spring Walk of Stars. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

Palm Springs Walk of Stars: Lauren Bacall star, 135 E. Tahquitz Canyon Way

- ↑ "Notes for Lauren Bacall". TCM. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ Kristen (September 9, 2012). "Bogie". Journeys in Classic Film. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ Goudas, John N. (February 29, 1980). "Kathryn Harrold cast as Bacall in 'Bogie'". The Boca Raton News. Google News Archive. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Bacall to Arms (1946)". Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Colin Stutz (August 12, 2014). "Lauren Bacall Dies: Her Top 5 Pop Song References". Billboard. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ↑ The Dakota Scrapbook at books.google.com. Accessed January 1, 2016

- ↑ The Cardinals (April 1, 2014). The Dakota Scrapbook: Volume 1. Exterior (1st ed.). Campfire Publishing. ISBN 0970081510. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Marshall Islands". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

The inhabited islands along the southern side of Majuro Atoll have been joined over time by landfill and a bridge to form a 30-mile road from Rita, on the extreme eastern end, to Laura, at the western end. Both villages were so code-named by U.S. forces in World War II after favorite pinups Rita Hayworth and Lauren Bacall.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lauren Bacall. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lauren Bacall |

- Lauren Bacall on IMDb

- Lauren Bacall at the Internet Broadway Database

- Lauren Bacall at the TCM Movie Database

- Lauren Bacall at AllMovie

- Works by or about Lauren Bacall in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

.jpg)