Latin spelling and pronunciation

Latin spelling, or Latin orthography, is the spelling of Latin words written in the scripts of all historical phases of Latin from Old Latin to the present. All scripts use the same alphabet, but conventional spellings may vary from phase to phase. The Roman alphabet, or Latin alphabet, was adapted from the Old Italic script to represent the phonemes of the Latin language. The Old Italic script had in turn been borrowed from the Greek alphabet, itself adapted from the Phoenician alphabet.

The Latin alphabet most resembles the Greek alphabet around 540 BC, as it appears on the red-figures pottery of the time.

Latin pronunciation continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was spoken in prior eras. A given phoneme may be represented by different letters in different periods. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best reconstruction of Classical Latin's phonemes (phonology) and the pronunciation and spelling used by educated people in the late Republic. This article then touches upon later changes and other variants.

Letterforms

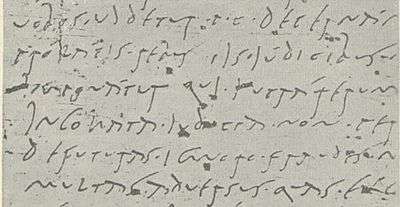

The forms of the Latin alphabet used during the Classical period did not distinguish between upper case and lower case. Roman inscriptions typically use Roman square capitals, which resemble modern capitals, and handwritten text often uses old Roman cursive, which includes letterforms similar to modern lowercase.

This article uses small caps for Latin text, representing Roman square capitals, and long vowels are marked with acutes, representing apices. In the tables below, Latin letters and digraphs are paired with the phonemes they usually represent in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Letters and phonemes

In ancient Latin spelling, individual letters mostly corresponded to individual phonemes, with three main exceptions:

- The vowel letters a, e, i, o, u, y represented both short and long vowels. The long vowels were often marked by apices during the Classical period ⟨Á É Ó V́ Ý⟩ and long i was written using a taller version ⟨I⟩, called i longa "long I": ⟨ꟾ⟩;[1] but now long vowels are sometimes written with a macron in modern editions (ā), while short vowels are marked with a breve (ă) in dictionaries when necessary.

- Some pairs of vowel letters, such as ae, represented either a diphthong in one syllable or two vowels in adjacent syllables.

- The letters i and u - v represented either the close vowels /i/ and /u/ or the semivowels /j/ and /w/.

In the tables below, Latin letters and digraphs are paired with the phonemes that they usually represent in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Consonants

This is a table of the consonant sounds of Classical Latin. Sounds in parentheses are allophones, sounds with an asterisk exist mainly in loanwords and sounds with a dagger (†) are phonemes only in some analyses.

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||

| Plosive | voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʷ† | ||

| voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ† | |||

| aspirated | pʰ* | tʰ* | kʰ* | ||||

| Fricative | voiced | z* | |||||

| voiceless | f | s | h | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | (ŋ) | ||||

| Rhotic | r | ||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||

Notes on phonetics

- The labialized velar stops /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ may both have been single phonemes rather than clusters like the /kw/ and /ɡw/ in English quick and penguin. /kʷ/ is more likely to have been a phoneme than /ɡʷ/. /kʷ/ occurs between vowels and counts as a single consonant in Classical Latin poetry, but /ɡʷ/ occurs only after [ŋ], where it cannot be identified as a single or double consonant.[2] /kʷ/ and [ɡʷ] were palatalized before a front vowel, becoming [kᶣ] and [ɡᶣ], as in quī [kᶣiː]

listen compared with quod [kʷɔd], and lingua [ˈlɪŋʷ.ɡʷa] compared with pinguis [ˈpɪŋ.ɡᶣɪs]. This sound change did not apply to /w/ in the same position: uī - vī [wiː].[3]

listen compared with quod [kʷɔd], and lingua [ˈlɪŋʷ.ɡʷa] compared with pinguis [ˈpɪŋ.ɡᶣɪs]. This sound change did not apply to /w/ in the same position: uī - vī [wiː].[3] - /kʷ ɡʷ/ before /u/ may have become [k ɡ] by dissimilation. This is suggested by the fact that equus and unguunt [ˈɛ.kʷʊs] and [ˈʊŋ.ɡʷʊnt] (Old Latin equos and unguont) are spelled ecus and ungunt, which may have indicated the pronunciations [ˈɛ.kʊs] and [ˈʊŋ.ɡʊnt]. These spellings may, however, simply indicate that c g before u were labialized like /kʷ ɡʷ/, so that writing a double uu was redundant.[4]

- The voiceless plosives /p t k kʷ/ in Latin were likely less aspirated than voiceless plosives at the beginning of words in English; for example, Latin /k/ was not as strongly aspirated as k in kind but more like k in English sky or look. However, there was no phonemic contrast between voiceless and aspirated plosives in native Latin words, and the voiceless plosives were probably somewhat aspirated at the beginnings of words and near /r/ and /l/.[5][6] Some Greek words beginning with the voiceless plosives /p t k/, when they were borrowed into colloquial Latin, were spelled with the graphemes used to represent voiced plosives b d g /b d ɡ/, e.g., Latin gubernator besides West Greek κυβερνάτας [kʉbernaːtaːs] (helmsman). That suggests that Latin speakers felt the Greek voiceless plosives to sound less aspirated than their own native equivalents.[7]

- The aspirated consonants /pʰ tʰ kʰ/ as distinctive phonemes were originally foreign to Latin, appearing in educated loanwords and names from Greek. In such cases, the aspiration was likely produced only by educated speakers.[5][6]

- /z/ was also not native to Classical Latin. It appeared in Greek loanwords starting around the first century BC, when it was probably pronounced [z] initially and doubled [zz] between vowels, in contrast to Classical Greek [dz] or [zd]. In Classical Latin poetry, the letter ⟨z⟩ between vowels always counts as two consonants for metrical purposes.[8][9]

- In Classical Latin, the coronal sibilant /s/ was likely unvoiced in all positions. In Old Latin, single /s/ between vowels was pronounced as voiced [z], but had changed to /r/ by rhotacism by the time of Classical Latin, as in gerō /ˈɡe.roː/ as compared with gestus /ˈɡes.tus/. Intervocalic /s/ in Classical usually derives from an earlier double /ss/ after a long vowel or diphthong, as in causa, cāsus from earlier caussa, cāssus;[10] or from loanwords, such as pausa from Greek παῦσις (pausis).

- In Old Latin, final /s/ after a short vowel was often lost, probably after first changing to [h] (debuccalization), as in the inscriptional form Cornelio for Cornelios (Classical Latin Cornelius). Often in the poetry of Plautus, Ennius, and Lucretius, final /s/ before a word beginning in a consonant did not make the preceding syllable heavy.[10]

- /f/ was labiodental in Classical Latin, but it may have been bilabial [ɸ] in Old Latin,[11] or perhaps [ɸ] in free variation with [f]. Lloyd, Sturtevant and Kent make this argument based on certain misspellings in inscriptions, the Proto-Indo-European phone *bʰ from which many instances of the Latin f descended (others are from *dʰ and *gʷʰ) and the way the sound appears to have behaved in Vulgar Latin, particularly in Spain.[12]

- In most cases /m/ was pronounced as a bilabial nasal. At the end of a word, however, it was generally lost beginning in Old Latin (except when another nasal or a plosive followed it), causing the preceding vowel to be lengthened and nasalized,[13] as in decem [ˈdɛ.kẽː]

listen . In Old Latin inscriptions, it is often omitted, as in viro for virom (Classical virum). It was frequently elided before a following vowel in Latin poetry, and it was lost without trace (apart from the lengthening) in the Romance languages,[14] except in monosyllabic words.

listen . In Old Latin inscriptions, it is often omitted, as in viro for virom (Classical virum). It was frequently elided before a following vowel in Latin poetry, and it was lost without trace (apart from the lengthening) in the Romance languages,[14] except in monosyllabic words. - /n/ assimilated to /m/ before labial consonants as in impar [ˈɪm.par]

listen < *in-par, to [ɱ] before /f/ (if it did not represent nasalization) and to [ŋ] before velar consonants, as in quīnque [ˈkᶣiːŋ.kᶣɛ]

listen < *in-par, to [ɱ] before /f/ (if it did not represent nasalization) and to [ŋ] before velar consonants, as in quīnque [ˈkᶣiːŋ.kᶣɛ]  listen .[15] This assimilation likely also occurred between the preposition in and a following word: in causā [ɪŋ ˈkau̯.saː], in pace [ɪm ˈpa.kɛ].[16]

listen .[15] This assimilation likely also occurred between the preposition in and a following word: in causā [ɪŋ ˈkau̯.saː], in pace [ɪm ˈpa.kɛ].[16] - /ɡ/ assimilated to a velar nasal [ŋ] before /n/.[17] Allen and Greenough say that a vowel before [ŋn] is always long,[18] but W. Sidney Allen says that is based on an interpolation in Priscian, and the vowel was actually long or short depending on the root, as for example rēgnum [ˈreːŋ.nũː] from the root of rēx [reːks], but magnus [ˈmaŋ.nʊs] from the root of magis [ˈma.ɡɪs].[19] /ɡ/ probably did not assimilate to [ŋ] before /m/. The cluster /ɡm/ arose by syncope, as for example tegmen [ˈtɛɡ.mɛn] from tegimen. Original /ɡm/ developed into /mm/ in flamma, from the root of flagrō.[2] At the start of a word, [ŋn] was reduced to [n], and this change was reflected in the orthography in later texts: gnātus [ˈnaː.tʊs] became nātus, gnōscō [ˈnoː.skoː] became nōscō.

- In Classical Latin, the rhotic /r/ was most likely an alveolar trill [r]. Gaius Lucilius likens it to the sound of a dog, and later writers describe it as being produced by vibration. In Old Latin, intervocalic /z/ developed into /r/ (rhotacism), suggesting an approximant like the English [ɹ], and /d/ was sometimes written as /r/, suggesting a tap [ɾ] like Spanish single r.[20]

- /l/ had two allophones in Latin: [l] and [ɫ]. Roman grammarians called these variants exīlis ('thin') and plēnus or pinguis ('full' or 'thick'). Those adjectives are used elsewhere for front and back vowels respectively, which suggests that the "thin" allophone was a plain alveolar lateral approximant [l], like the clear /l/ in English leaf in some English dialects or that of languages like Spanish or German, while the "full" or "thick" allophone was velarized like the English dark /l/ in full. It is partly uncertain where these allophones occurred. Sihler and Allen agree that /l/ was clear when the sound was doubled as /ll/, and dark when it occurred before another consonant or at the end of a word, but disagree on whether clear or dark l occurred before vowels. Sihler says that /l/ was clear before /i/ and dark before other vowels, but Allen says that /l/ was dark before back vowels in pre-Classical Latin and clear before both front and back vowels in Classical Latin. This represents a partial agreement, however, in that Sihler argues the Classical Latin /l/ had three degrees of velarization, with a darker enunciation before consonants than vowels.[21][22]

- /j/ generally appeared only at the beginning of words, before a vowel, as in iaceō /ˈja.kɛ.oː/, except in compound words such as adiaceō /adˈja.kɛ.oː/

listen . Between vowels, this sound was generally not found as a single consonant, only as doubled /jː/, as in cuius /ˈkuj.jus/

listen . Between vowels, this sound was generally not found as a single consonant, only as doubled /jː/, as in cuius /ˈkuj.jus/  listen , except in compound words such as trāiectus /traːˈjek.tus/. /j/ varied with /i/ in the same morpheme in iam /jãː/ and etiam /ˈe.ti.ãː/, and in poetry, one could be replaced with the other for the purposes of meter.[23]

listen , except in compound words such as trāiectus /traːˈjek.tus/. /j/ varied with /i/ in the same morpheme in iam /jãː/ and etiam /ˈe.ti.ãː/, and in poetry, one could be replaced with the other for the purposes of meter.[23] - /w/ was pronounced as an approximant until the first century AD, when /w/ and /b/ began to develop into fricatives. In poetry, /w/ and /u/ could be replaced with each other, as in /ˈsi.lu.a/ for silva /ˈsil.wa/ and /ˈɡen.wa/ for genua /ˈɡe.nu.a/. Unlike /j/, it was not doubled as /wː/ or /ww/ between vowels, except in Greek loanwords: cavē /ˈka.weː/, but Evander /ewˈwan.der/ from Εὔανδρος.[24]

Notes on spelling

- Doubled consonant letters, such as cc, ss, represented geminated (doubled or long) consonants: /kː sː/. In Old Latin, geminate consonants were written singly like single consonants, until the middle of the 2nd century BC, when they began to be doubled in writing.[note 2] Grammarians mention the marking of double consonants with the sicilicus, a diacritic in the shape of a sickle. This mark appears in a few inscriptions of the Augustan era.[25]

- c and k both represent the velar stop /k/; qu represents the labialized velar stop /kʷ/. The letters q and c distinguish minimal pairs between /ku/ and /kʷ/, such as cui /kui̯/ and quī /kʷiː/.[26] In Classical Latin, k appeared in only a few words, such as kalendae.[27]

- x represented the consonant cluster /ks/. In Old Latin, this sequence was also spelled as ks, cs, and xs. X was borrowed from the Western Greek alphabet, in which the letterform of chi Χ was pronounced as /ks/. In the standard Ionic alphabet, used for modern editions of Ancient Greek, on the other hand, Χ represented /kʰ/, and the letter xi Ξ represented /ks/.[28]

- In Old Latin inscriptions, /k/ and /ɡ/ were not distinguished. They were both represented by c before e and i, q before o and u, and k before consonants and a.[1] The letterform of c derives from Greek gamma Γ, which represented /ɡ/, but its use for /k/ may come from Etruscan, which did not distinguish voiced and voiceless plosives. In Classical Latin, c represented /ɡ/ only in c and cn, the abbreviations of the praenomina (first names) Gaius and Gnaeus.[27][29]

- The letter g was created in the third century BC to distinguish the voiced /ɡ/ from voiceless /k/.[30] Its letterform derived from c by the addition of a diacritic or stroke. Plutarch attributes this innovation to Spurius Carvilius Ruga around 230 BC,[1] but it may have originated with Appius Claudius Caecus in the fourth century BC.[31]

- The combination gn probably represented the consonant cluster [ŋn], at least between vowels, as in agnus [ˈaŋ.nʊs]

listen .[13][32] Vowels before this cluster were sometimes long and sometimes short.[19]

listen .[13][32] Vowels before this cluster were sometimes long and sometimes short.[19] - The digraphs ph, th and ch represented the aspirated plosives /pʰ/, /tʰ/ and /kʰ/. They began to be used in writing around 150 B.C.,[30] primarily as a transcription of Greek phi Φ, theta Θ and chi Χ, as in Philippus, cithara, and achāia. Some native words were later also written with these digraphs, such as pulcher, lachrima, gracchus, triumphus, probably representing aspirated allophones of the voiceless plosives near /r/ and /l/. Aspirated plosives and the glottal fricative /h/ were also used hypercorrectively, an affectation satirized in Catullus 84.[5][6]

- In Old Latin, Koine Greek initial /z/ and /zz/ between vowels were represented by s and ss, as in sona from ζώνη and massa from μᾶζα. Around the second and first centuries B.C., the Greek letter zeta Ζ was adopted to represent /z/ and /zz/.[9] However, the Vulgar Latin spellings z or zi for earlier di and d before e, and the spellings di and dz for earlier z, suggest the pronunciation /dz/, as for example ziomedis for diomedis, and diaeta for zeta.[33]

- In ancient times u and i represented the approximant consonants /w/ and /j/, as well as the close vowels /u(ː)/ and /i(ː)/.

- i representing the consonant /j/ was usually not doubled in writing so a single i represented double /jː/ or /jj/ and the sequences /ji/ and /jːi/, as in cuius for *cuiius /ˈkuj.jus/, conicit for *coniicit /ˈkon.ji.kit/, and rēicit for *reiiicit /ˈrej.ji.kit/. Both the consonantal and vocalic pronunciations of i could occur in some of the same environments: compare māius /ˈmaj.jus/ with Gāius /ˈɡaː.i.us/, and Iūlius /ˈjuː.li.us/ with Iūlus /iˈuː.lus/. The vowel before a doubled /jː/ is sometimes marked with a macron, as in cūius. it indicates not that the vowel is long but that the first syllable is heavy from the double consonant.[23]

- v between vowels represented single /w/ in native Latin words but double /ww/ in Greek loanwords. Both the consonantal and vocalic pronunciations of v sometimes occurred in similar environments, as in genua [ˈɡɛ.nʊ.a] and silva [ˈsɪl.wa].[24][34]

Vowels

Monophthongs

Latin has ten native vowels, spelled a, e, i, o, u. In Classical Latin, each vowel had short and long versions: /a ɛ ɪ ɔ ʊ/ and /aː eː iː oː uː/. The long versions of the close and mid vowels e, i, o, u had a different vowel quality from the short versions, so that long /eː, oː/ were similar to short /ɪ, ʊ/. Some loanwords from Greek had the vowel y, which was pronounced as /y yː/ by educated speakers but approximated with the native vowels u and i by less educated speakers.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| Close | iː | ɪ | uː | ʊ | ||

| Mid | eː | ɛ | oː | ɔ | ||

| Open | aː | a | ||||

Long and short vowels

Each vowel letter (with the possible exception of y) represents at least two phonemes. a can represent either short /a/ or long /aː/, e represents either /e/ or /eː/, etc.

Short mid vowels (/e o/) and close vowels (/i u/) were pronounced with a different quality from their long counterparts, being also more open: [ɛ], [ɔ], [ɪ] and [ʊ]. This opening made the short vowels i u [ɪ ʊ] similar in quality to long é ó [eː oː] respectively. i é and u ó were often written in place of each other in inscriptions:[35]

- trebibos for tribibus [ˈtrɪ.bɪ.bʊs]

- minsis for mensis [ˈmẽː.sɪs]

- sob for sub [sʊb]

- punere for pōnere [ˈpoː.næ.rɛ]

Short /e/ most likely had a more open allophone before /r/ and tended toward near-open [æ].[36]

Short /e/ and /i/ were probably pronounced closer when they occurred before another vowel. mea was written as mia in inscriptions. Short /i/ before another vowel is often written with i longa, as in dīes, indicating that its quality was similar to that of long /iː/ and is almost never confused with e in this position.[37]

Adoption of Greek upsilon

y was used in Greek loanwords with upsilon Υ. This letter represented the close front rounded vowel, both short and long: /y yː/.[38] Latin did not have this sound as a distinctive phoneme, and speakers tended to pronounce such loanwords with /u uː/ in Old Latin and /i iː/ in Classical and Late Latin if they were unable to produce /y yː/.

Sonus medius

An intermediate vowel sound (likely a close central vowel [ɨ] or possibly its rounded counterpart [ʉ]), called sonus medius, can be reconstructed for the classical period.[39] Such a vowel is found in documentum, optimus, lacrima (also spelled docimentum, optumus, lacruma) and other words. It developed out of a historical short /u/, later fronted by vowel reduction. In the vicinity of labial consonants, this sound was not as fronted and may have retained some rounding.[40]

Vowel nasalization

|

Examples of nasalized vowels at ends of words and before -ns-, -nf- sequences

monstrum

mensis

infans, infantem

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Vowels followed by a nasal consonant were allophonically realised as long nasal vowels in two environments:[41]

- Before word-final m:[14]

- monstrum /ˈmon.strum/ > [ˈmõː.strũː].

- dentem /ˈden.tem/ > [ˈdɛn.tẽː]

- Before nasal consonants followed by a fricative:[16]

- censor /ˈken.sor/ > [ˈkẽː.sɔr] (in early inscriptions, often written as cesor)

- consul /ˈkon.sul/ > [ˈkõː.sʊl] (often written as cosol and abbreviated as cos)

- inferōs /ˈin.fe.roːs/ > [ˈĩː.fæ.roːs] (written as iferos)

Those long nasal vowels had the same quality as ordinary long vowels. In Vulgar Latin, the vowels lost their nasalisation, and they merged with the long vowels (which were themselves shortened by that time). This is shown by many forms in the Romance languages, such as Spanish costar from Vulgar Latin cōstāre (originally constāre) and Italian mese from Vulgar Latin mēse (Classical Latin mensem). On the other hand, the short vowel and /n/ was restored in French enseigne and enfant from insignia and infantem (e is the normal development of Latin short i), likely by analogy with other forms beginning in the prefix in-.[42]

When a final -m occurred before a plosive or nasal in the next word, however, it was pronounced as a nasal at the place of articulation of the following consonant. For instance, tan dūrum [tan ˈduː.rũː] was written for tam dūrum in inscriptions, and cum nōbīs [kʊn ˈnoː.biːs] was a double entendre,[14] possibly for cunnō bis [ˈkʊnnoː bɪs].

Diphthongs

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | ui ui̯ | |

| Mid | ei ei̯ eu eu̯ | oe oi̯ ~ oe̯ ou ou̯ |

| Open | ae ai̯ ~ ae̯ au au̯ | |

ae, oe, au, ei, eu could represent diphthongs: ae represented /ae̯/, oe represented /oe̯/, au represented /au̯/, ei represented /ei̯/, and eu represented /eu̯/. ui sometimes represented the diphthong /ui̯/, as in cui ![]() listen and huic.[26]

listen and huic.[26]

If there is a tréma above the second vowel, both vowels are pronounced separately: aë [a.ɛ], aü [a.ʊ], eü [ɛ.ʊ] and oë [ɔ.ɛ].

In Old Latin, ae, oe were written as ai, oi and probably pronounced as [ai̯, oi̯], with a fully closed second element, similar to the final syllable in French ![]() travail . In the late Old Latin period, the last element of the diphthongs was lowered to [e],[43] so that the diphthongs were pronounced /ae̯/ and /oe̯/ in Classical Latin, similar to the diphthongs in English

travail . In the late Old Latin period, the last element of the diphthongs was lowered to [e],[43] so that the diphthongs were pronounced /ae̯/ and /oe̯/ in Classical Latin, similar to the diphthongs in English ![]() high and

high and ![]() boy. They were then monophthongized to /ɛː/ and /eː/, starting in rural areas at the end of the Republican period.[note 3] The process, however, does not seem to have been completed before the 3rd century AD in Vulgar Latin, and some scholars say that it may have been regular by the 5th century.[44]

boy. They were then monophthongized to /ɛː/ and /eː/, starting in rural areas at the end of the Republican period.[note 3] The process, however, does not seem to have been completed before the 3rd century AD in Vulgar Latin, and some scholars say that it may have been regular by the 5th century.[44]

Vowel and consonant length

Vowel and consonant length were more significant and more clearly defined in Latin than in modern English. Length is the duration of time that a particular sound is held before proceeding to the next sound in a word. Unfortunately, "vowel length" is a confusing term for English speakers, who, in their language, call "long vowels" what are usually diphthongs rather than monophthongs. (That is a relic of the Great Vowel Shift, during which vowels that had once been pronounced phonemically longer turned into diphthongs.) In the modern spelling of Latin, especially in dictionaries and academic work, macrons are frequently used to mark long vowels: ⟨ā ē ī ō ū ȳ⟩, while the breve is sometimes used to indicate that a vowel is short: ⟨ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ y̆⟩.

Long consonants were usually indicated through doubling, but ancient Latin orthography did not distinguish between the vocalic and consonantal uses of i and v. Vowel length was indicated only intermittently in classical sources and even then through a variety of means. Later medieval and modern usage tended to omit vowel length altogether. A short-lived convention of spelling long vowels by doubling the vowel letter is associated with the poet Lucius Accius. Later spelling conventions marked long vowels with an apex (a diacritic similar to an acute accent) or, in the case of long i, by increasing the height of the letter (long i); in the second century AD, those were given apices as well.[45] Distinctions of vowel length became less important in later Latin and have ceased to be phonemic in the modern Romance languages, in which the previous long and short versions of the vowels have been either lost or replaced by other phonetic contrasts.

A minimal set showing both long and short vowels and long and short consonants is ānus /ˈaː.nus/ ('buttocks'), annus /ˈan.nus/ ('year'), anus /ˈa.nus/ ('old woman').

Table of orthography

| Latin grapheme | Latin phone | English approximation |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨c⟩, ⟨k⟩ | [k] | Always hard as k in sky, never soft as in cellar, cello, or social |

| ⟨t⟩ | [t] | As t in stay, never as t in nation |

| ⟨s⟩ | [s] | As s in say, never as s in rise or issue |

| ⟨g⟩ | [ɡ] | Always hard as g in good, never soft as g in gem |

| ⟨gn⟩ | [ŋn] | As ngn in wingnut |

| ⟨n⟩ | [n] | As n in man |

| [ŋ] | Before ⟨c⟩, ⟨x⟩, and ⟨g⟩, as ng in sing | |

| ⟨l⟩ | [l] | When doubled ⟨ll⟩ and before ⟨i⟩, as clear l in link (l exilis)[46][47] |

| [ɫ] | In all other positions, as dark l in bowl (l pinguis) | |

| ⟨qu⟩ | [kʷ] | Similar to qu in quick, never as qu in antique |

| ⟨v⟩ | [w] | Sometimes at the beginning of a syllable, or after ⟨g⟩ and ⟨s⟩, as w in wine, never as v in vine |

| ⟨i⟩ | [j] | Sometimes at the beginning of a syllable, as y in yard, never as j in just |

| [jj] | Doubled between vowels, as y y in toy yacht | |

| ⟨x⟩ | [ks] | A letter representing ⟨c⟩ + ⟨s⟩: as x in English axe, never as x in example |

| Latin grapheme |

Latin phone |

English approximation | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⟨a⟩ | [a] | similar to u in cut when short | |

| [aː] | similar to a in father when long | ||

| ⟨e⟩ | [ɛ] | as e in pet when short | |

| [eː] | similar to ey in they when long | ||

| ⟨i⟩ | [ɪ] | as i in sit when short | |

| [iː] | similar to i in machine when long | ||

| ⟨o⟩ | [ɔ] | as o in sort when short | |

| [oː] | similar to o in holy when long | ||

| ⟨u⟩ | [ʊ] | similar to u in put when short | |

| [uː] | similar to u in true when long | ||

| ⟨y⟩ | [ʏ] | as in German Stück when short (or as short u or i) | |

| [yː] | as in German früh when long (or as long u or i) |

Syllables and stress

Old Latin stress

In Old Latin, as in Proto-Italic, stress normally fell on the first syllable of a word.[48] During this period, the word-initial stress triggered changes in the vowels of non-initial syllables, the effects of which are still visible in classical Latin. Compare for example:

- faciō 'I do/make', factus 'made'; pronounced /ˈfa.ki.oː/ and /ˈfak.tus/ in later Old Latin and Classical Latin.

- afficiō 'I affect', affectus 'affected'; pronounced /ˈaf.fi.ki.oː/ and /ˈaf.fek.tus/ in Old Latin following vowel reduction, /af.ˈfi.ki.oː/ and /af.ˈfek.tus/ in Classical Latin.

In the earliest Latin writings, the original unreduced vowels are still visible. Study of this vowel reduction, as well as syncopation (dropping of short unaccented syllables) in Greek loan words, indicates that the stress remained word-initial until around the time of Plautus, the 3rd century BC.[49] The placement of the stress then shifted to become the pattern found in classical Latin.

Classical Latin syllables and stress

In Classical Latin, stress changed. It moved from the first syllable to one of the last three syllables, called the antepenult, the penult, and the ultima (short for antepaenultima 'before almost last', paenultima 'almost last', and ultima syllaba 'last syllable'). Its position is determined by the syllable weight of the penult. If the penult is heavy, it is accented; if the penult is light and there are more than two syllables, the antepenult is accented.[50] In a few words originally accented on the penult, accent is on the ultima because the two last syllables have been contracted, or the last syllable has been lost.[51]

Syllable

To determine stress, syllable weight of the penult must be determined. In order to determine syllable weight, words must be broken up into syllables.[52] In the following examples, syllable structure is represented using these symbols: C (a consonant), K (a stop), R (a liquid), and V (a short vowel), VV (a long vowel or diphthong).

Nucleus

Every short vowel, long vowel, or diphthong belongs to a single syllable. This vowel forms the syllable nucleus. Thus magistrārum has four syllables, one for every vowel (a i ā u: V V VV V), aereus has three (ae e u: VV V V), tuō has two (u ō: V VV), and cui has one (ui: VV).[53]

Onset and coda

A consonant before a vowel, or a consonant cluster at the beginning of a word, is placed in the same syllable as the following vowel. This consonant or consonant cluster forms the syllable onset.[53]

- fēminae /feː.mi.nae̯/ (CVV.CV.CVV)

- vidēre /wi.deː.re/ (CV.CVV.CV)

- puerō /pu.e.roː/ (CV.V.CVV)

- beātae /be.aː.tae̯/ (CV.VV.CVV)

- graviter /ɡra.wi.ter/ (CCV.CV.CVC)

- strātum /straː.tum/ (CCCVV.CVC)

After this, if there is an additional consonant inside the word, it is placed at the end of the syllable. This consonant is the syllable coda. Thus if a consonant cluster of two consonants occurs between vowels, they are broken up between syllables: one goes with the syllable before, the other with the syllable after.[54]

- puella /pu.el.la/ (CV.VC.CV)

- supersum /su.per.sum/ (CV.CVC.CVC)

- coāctus /ko.aːk.tus/ (CV.VVC.CVC)

- intellēxit /in.tel.leːk.sit/ (VC.CVC.CVVC.CVC)

There are two exceptions. A consonant cluster of a stop p t c b d g followed by a liquid l r between vowels usually goes to the syllable after it, although it is also sometimes broken up like other consonant clusters.[54]

- volucris /wo.lu.kris/ or /wo.luk.ris/ (CV.CV.KRVC or CV.CVK.RVC)

Heavy and light syllables

As shown in the examples above, Latin syllables have a variety of possible structures. Here are some of them. The first four examples are light syllables, and the last six are heavy. All syllables have at least one V (vowel). A syllable is heavy if it has another V or a VC after the first V. In the table below, the extra V or VC is bolded, indicating that it makes the syllable heavy.

| V | |||||

| C | V | ||||

| C | C | V | |||

| C | C | C | V | ||

| C | V | V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | V | C | |||

| C | V | V | C | ||

| V | V | ||||

| V | C | ||||

| V | V | C |

Thus, a syllable is heavy if it ends in a long vowel or diphthong, a short vowel and a consonant, a long vowel and a consonant, or a diphthong and a consonant. Syllables ending in a diphthong and consonant are rare in Classical Latin.

The syllable onset has no relationship to syllable weight; both heavy and light syllables can have no onset or an onset of one, two, or three consonants.

A syllable that is heavy because it ends in a long vowel or diphthong is traditionally called syllaba nātūrā longa ('syllable long by nature'), and a syllable that is heavy because it ends in a consonant is called positióne longa ('long by position'). These terms are translations of Greek συλλαβὴ μακρά φύσει (syllabḕ makrá phýsei) and μακρὰ θέσει (makrà thései), respectively. longa and μακρά (makrá) are the same terms used for long vowels. This article uses the words heavy and light for syllables, and long and short for vowels, since the two are not the same.[54]

Stress rule

In a word of three or more syllables, the weight of the penult determines where the accent is placed. If the penult is light, accent is placed on the antepenult; if it is heavy, accent is placed on the penult.[54] Below, stress is marked by placing the stress mark [ˈ] before the stressed syllable.

| volucris | fēminae | puerō |

| /ˈwo.lu.kris/ | /ˈfeː.mi.nae̯/ | /ˈpu.e.roː/ |

| CV.CV.CCVC | CVV.CV.CVV | CV.V.CVV |

| volucris | vidēre | intellēxit | beātae | puella | coāctus |

| CV.CVC.CVC | CV.CVV.CV | VC.CVC.CVVC.CVC | CV.VV.CVV | CV.VC.CV | CV.VVC.CVC |

| /woˈluk.ris/ | /wiˈdeː.re/ | /in.telˈleːk.sit/ | /beˈaː.tae̯/ | /puˈel.la/ | /koˈaːk.tus/ |

Iambic shortening

Iambic shortening or brevis brevians is vowel shortening that occurs in words of the type light–heavy, where the light syllable is stressed. By this sound change, words like egō, modō, benē, amā with long final vowel change to ego, modo, bene, ama with short final vowel.[55]

Elision

Where one word ended with a vowel (including a nasalized vowel, represented by a vowel plus m) and the next word began with a vowel, the former vowel, at least in verse, was regularly elided; that is, it was omitted altogether, or possibly (in the case of /i/ and /u/) pronounced like the corresponding semivowel. When the second word was est or et, a different form of elision sometimes occurred (prodelision): the vowel of the preceding word was retained and the e was elided instead. Elision also occurred in Ancient Greek but in that language it is shown in writing by the vowel in question being replaced by an apostrophe, whereas in Latin elision is not indicated at all in the orthography, but can be deduced from the verse form. Only occasionally is it found in inscriptions, as in scriptust for scriptum est.[56]

Latin spelling and pronunciation today

Spelling

Modern usage, even for classical Latin texts, varies in respect of I and V. During the Renaissance, the printing convention was to use I (upper case) and i (lower case) for both vocalic /i/ and consonantal /j/, to use V in the upper case and in the lower case to use v at the start of words and u subsequently within the word regardless of whether /u/ and /w/ was represented.[57]

Many publishers (such as Oxford University Press) have adopted the convention of using I (upper case) and i (lower case) for both /i/ and /j/, and V (upper case) and u (lower case) for both /u/ and /w/.

An alternative approach, less common today, is to use i and u only for the vowels and j and v for the approximants.

Most modern editions, however, adopt an intermediate position, distinguishing between u and v but not between i and j. Usually, the non-vocalic v after q or g is still printed as u rather than v, probably because in this position it did not change from /w/ to /v/ in post-classical times.[note 4]

Textbooks and dictionaries indicate the length of vowels by putting a macron or horizontal bar above the long vowel, but it is not generally done in regular texts. Occasionally, mainly in early printed texts up to the 18th century, one may see a circumflex used to indicate a long vowel where this makes a difference to the sense, for instance Româ /ˈroːmaː/ ('from Rome' ablative) compared to Roma /ˈroːma/ ('Rome' nominative).[58] Sometimes, for instance in Roman Catholic service books, an acute accent over a vowel is used to indicate the stressed syllable. It would be redundant for one who knew the classical rules of accentuation and made the correct distinction between long and short vowels, but most Latin speakers since the 3rd century have not made any distinction between long and short vowels, but they have kept the accents in the same places; thus, the use of accent marks allows speakers to read a word aloud correctly even if they never heard it spoken aloud.

Pronunciation

Post-Medieval Latin

Since around the beginning of the Renaissance period onwards, with the language being used as an international language among intellectuals, pronunciation of Latin in Europe came to be dominated by the phonology of local languages, resulting in a variety of different pronunciation systems.

Loan words and formal study

When Latin words are used as loanwords in a modern language, there is ordinarily little or no attempt to pronounce them as the Romans did; in most cases, a pronunciation suiting the phonology of the receiving language is employed.

Latin words in common use in English are generally fully assimilated into the English sound system, with little to mark them as foreign, for example, cranium, saliva. Other words have a stronger Latin feel to them, usually because of spelling features such as the digraphs ae and oe (occasionally written as ligatures: æ and œ, respectively), which both denote /iː/ in English. The digraph ae or ligature æ in some words tend to be given an /aɪ/ pronunciation, for example, curriculum vitae.

However, using loan words in the context of the language borrowing them is a markedly different situation from the study of Latin itself. In this classroom setting, instructors and students attempt to recreate at least some sense of the original pronunciation. What is taught to native anglophones is suggested by the sounds of today's Romance languages, the direct descendants of Latin. Instructors who take this approach rationalize that Romance vowels probably come closer to the original pronunciation than those of any other modern language (see also the section below on "Derivative languages").

However, other languages—including Romance family members—all have their own interpretations of the Latin phonological system, applied both to loan words and formal study of Latin. But English, Romance, or other teachers do not always point out that the particular accent their students learn is not actually the way ancient Romans spoke.

Ecclesiastical pronunciation

Because of the central position of Rome within the Catholic Church, an Italian pronunciation of Latin became commonly accepted, but this was not the case until the latter part of the 19th century. This pronunciation corresponds to that of the Latin-derived words in Italian. Before then, the pronunciation of Latin in church was the same as the pronunciation as Latin in other fields, and tended to reflect the sound values associated with the nationality of the speaker.[59]

The following are the main points that distinguish modern ecclesiastical pronunciation from Classical Latin pronunciation:

- Vowel length is not phonemic. As a result the automatic stress accent of Classical Latin, which was dependent on vowel length, becomes a phonemic one in Ecclesiastical Latin. (Some Ecclesiastical texts mark the stress with an acute accent in words of three or more syllables.)

- The digraphs ae and oe (sometimes written as ligatures æ and œ) represent /ɛ/.[60]

- c denotes [t͡ʃ] (as in English ⟨ch⟩) before ae (æ), oe (œ), e, i or y.

- g denotes [d͡ʒ] (as in English ⟨j⟩) before ae (æ), oe (œ), e, i or y.

- h is silent except in two words: mihi and nihil, where it represents /k/ (in the Middle Ages, these words were spelled michi and nichil).[61][note 5]

- s between vowels represents /z/ or /s/;[62] sc before ae (æ), oe (œ), e, i or y. represents /ʃ/.

- ti, if followed by a vowel, not word-initial or stressed, and not preceded by s, t, or x, represents [t͡si].[60]

- the letter v when it starts a syllable is pronounced /v/, and not /w/ as in classical Latin. Between g or q and a vowel, it retains the ancient /w/ pronunciation, and as a syllable nucleus it retains /u/. Unlike in the ancient orthography, the letter v is now written v when it is pronounced /v/, but u when it is pronounced /w/ or /u/.

- th represents /t/.

- ph represents /f/.

- ch represents /k/.

- y represents /i/.

- gn represents /ɲ/.

- x represents /ks/, the /s/ of which merges with a following c that precedes ae (æ), oe (œ), e, i or y to form /ʃ/, as in excelsis /ekˈʃelsis/[60]

- z represents /dz/.

- Word-final m and n are pronounced fully, with no nasalization of the preceding vowel.

In his Vox Latina: A guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin, William Sidney Allen remarked that this pronunciation, used by the Catholic Church in Rome and elsewhere, and whose adoption Pope Pius X recommended in a 1912 letter to the Archbishop of Bourges, "is probably less far removed from classical Latin than any other 'national' pronunciation"; but, as can be seen from the table above, there are, nevertheless, very significant differences.[63] The introduction to the Liber Usualis indicates that Ecclesiastical Latin pronunciation should be used at Church liturgies.[64] Ecclesiastical pronunciation is also the preferred pronunciation of Catholics whenever speaking Latin even if not as part of liturgy. The Pontifical Academy for Latin is the pontifical academy in the Vatican that is charged with the dissemination and education of Catholics in the Latin language.

Outside of Austria and Germany it is the most widely used standard in choral singing which, with a few exceptions like Stravinsky's Oedipus rex, is concerned with liturgical texts. Anglican choirs adopted it when classicists abandoned traditional English pronunciation after World War II. The rise of historically informed performance and the availability of guides such as Copeman's Singing in Latin has led to the recent revival of regional pronunciations.

Pronunciation shared by Vulgar Latin and Romance languages

Because it gave rise to many modern languages, Latin did not strictly "die"; it merely evolved over the centuries in diverse ways. The local dialects of Vulgar Latin that emerged eventually became modern Italian, Spanish, French, Romanian, Portuguese, Catalan, Romansh, Dalmatian, Sardinian, and many others.

Key features of Vulgar Latin and Romance languages include:

- Almost total loss of /h/ and final unstressed /m/.

- Conversion of the distinction of vowel length into a distinction of height, and subsequent merger of some of these phonemes. Most Romance languages merged short /u/ with long /oː/ and short /i/ with long /eː/.

- Monophthongization of /ae̯/ into /ɛː/ and /oe̯/ into /eː/.

- Loss of marginal phonemes such as aspirates (/pʰ/, /tʰ/, and /kʰ/), which became tenues, and the close front-rounded vowel [y], which became unrounded.

- Loss of /n/ before /s/[65] (CL spōnsa > VL spōsa) but this influence on the later development of Romance languages was limited from written influence, analogy, and learned borrowings.[66]

- Palatalization of /k/ before /e/ and /i/ (not in all varieties), probably first into /kʲ/ and then /tʲ/ before it finally developed into /ts/ or /tʃ/.[67]

- Palatalization of /ɡ/ before /e/ and /i/, and of /j/, into /dʒ/ (not in all varieties) and then further into /ʒ/ in some Romance varieties.[67]

- Palatalization of /ti/ followed by a vowel (if not preceded by s, t, x) into /tsj/. It merged with /ts/ in dialects in which /k/ had developed into this sound, but it remained separate elsewhere (such as Italian).

- Palatalization of /li/ and /ni/ followed by a vowel into /ʎ/ and /ɲ/. /ŋn/ (orthographic gn) also coalesced to become /ɲ/.

- The change of /w/ (except after /k/) and /b/ between vowels, into /β/.

Examples

The following examples are both in verse, which demonstrates several features more clearly than prose.

From Classical Latin

Virgil's Aeneid, Book 1, verses 1–4. Quantitative metre (dactylic hexameter). Translation: "I sing of arms and the man, who, driven by fate, came first from the borders of Troy to Italy and the Lavinian shores; he [was] much afflicted both on lands and on the deep by the power of the gods, because of fierce Juno's vindictive wrath."

- Ancient Roman orthography (before 2nd century)[note 6]

- ARMA·VIRVMQVE·CANÓ·TRÓIAE·QVꟾ·PRꟾMVS·ABÓRꟾS

- ꟾTALIAM·FÁTÓ·PROFVGVS·LÁVꟾNIAQVE·VÉNIT

- LꟾTORA·MVLTVM·ILLE·ETTERRꟾS·IACTÁTVS·ETALTÓ

- Vꟾ·SVPERVM·SAEVAE·MEMOREM·IV́NÓNIS·OBꟾRAM

- Traditional (19th century) English orthography

- Arma virúmque cano, Trojæ qui primus ab oris

- Italiam, fato profugus, Lavíniaque venit

- Litora; multùm ille et terris jactatus et alto

- Vi superum, sævæ memorem Junonis ob iram.

- Modern orthography with macrons

- Arma virumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs

- Ītaliam, fātō profugus, Lāvīniaque vēnit

- Lītora; multum ille et terrīs iactātus et altō

- Vī superum, saevae memorem Iūnōnis ob īram.

- Modern orthography without macrons

- Arma virumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab oris

- Italiam, fato profugus, Laviniaque venit

- Litora; multum ille et terris iactatus et alto

- Vi superum, saevae memorem Iunonis ob iram.

- [Reconstructed] Classical Roman pronunciation

- [ˈarma wɪˈrũːkᶣɛ ˈkanoː | ˈtroːjae̯ | kᶣiː ˈpriːmʊs aˈboːriːs |

- iːˈtaliãː | ˈfaːtoː ˈprɔfʊɡʊs | laːˈwiːnjakᶣɛ ˈweːnɪt

- ˈliːtɔra ‖ ˈmʊɫtᶣ ɪ̃ll ɛt ˈtɛrriːs jakˈtaːtʊs | ɛˈtaɫtoː

- wiː ˈsʊpærũː | ˈsae̯wae̯ ˈmɛmɔrẽː juːˈnoːnɪs ɔˈbiːrãː

Note the elisions in mult(um) and ill(e) in the third line. For a fuller discussion of the prosodic features of this passage, see Dactylic hexameter.

Some manuscripts have "Lāvīna" rather than "Lāvīnia" in the second line.

From Medieval Latin

Beginning of Pange Lingua Gloriosi Corporis Mysterium by Thomas Aquinas (13th century). Rhymed accentual metre. Translation: "Extol, [my] tongue, the mystery of the glorious body and the precious blood, which the fruit of a noble womb, the king of nations, poured out as the price of the world."

1. Traditional orthography as in Roman Catholic service books (stressed syllable marked with an acute accent on words of three syllables or more).

- Pange lingua gloriósi

- Córporis mystérium,

- Sanguinísque pretiósi,

- quem in mundi prétium

- fructus ventris generósi

- Rex effúdit géntium.

2. "Italianate" ecclesiastical pronunciation

- [ˈpandʒe ˈliŋɡwa ɡloriˈoːzi

- ˈkɔrporis misˈtɛːrium

- saŋɡwiˈniskwe prettsiˈoːzi

- kwem in ˈmundi ˈprɛttsium

- ˈfruktus ˈvɛntris dʒeneˈroːzi

- rɛks efˈfuːdit ˈdʒentsium

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Latin pronunciation. |

- Latin alphabet

- Latin grammar

- Latin regional pronunciation

- Traditional English pronunciation of Latin

- Deutsche Aussprache des Lateinischen (in German) – traditional German pronunciation

- Schulaussprache des Lateinischen (in German) – revised "school" pronunciation

- Französische Aussprache des Lateins (in German) - traditional French pronunciation

Notes

- ↑ Appius Claudius

C(ai) f(ilius) Caecus

censor co(n)s(ul) bis dict(ator) interrex III

pr(aetor) II aed(ilis) cur(ulis) II q(uaestor) tr(ibunus) mil(itum) III com(-)

plura oppida de( )Samnitibus cepit

Sabinorum et Tuscórum exerci(-)

tum fudit pácem fierí cum Pyrrho

rege prohibuit in censura uiam

Appiam strauit etaquam in

urbem( )adduxit aedem Bellonae

fecit - ↑ epistula ad tiburtes, a letter by praetor Lucius Cornelius from 159 BC, contains the first examples of doubled consonants in the words potuisse, esse, and peccatum (Clackson & Horrocks 2007, pp. 147, 149).

- ↑ The simplification was already common in rural speech as far back as the time of Varro (116 BC – 27 BC): cf. De lingua Latina, 5:97 (referred to in Smith 2004, p. 47).

- ↑ This approach is also recommended in the help page for the Latin Wikipedia.

- ↑ This pronunciation of mihi and nihil may have been an attempt to reintroduce /h/ intervocalically, where it seems to have been lost even in literary Latin by the end of the Republican period (Smith 2004, p. 48) as indicated by the alternative Classical spellings mī and nīl.

- ↑ "The word-divider is regularly found on all good inscriptions, in papyri, on wax tablets, and even in graffiti from the earliest Republican times through the Golden Age and well into the Second Century. ... Throughout these periods the word-divider was a dot placed half-way between the upper and the lower edge of the line of writing. ... As a rule, interpuncta are used simply to divide words, except that prepositions are only rarely separated from the word they govern, if this follows next. ... The regular use of the interpunct as a word-divider continued until sometime in the Second Century, when it began to fall into disuse, and Latin was written with increasing frequency, both in papyrus and on stone or bronze, in scriptura continua." Wingo 1972, pp. 15, 16

References

- 1 2 3 Sihler 1995, pp. 20–22, §25: the Italic alphabets

- 1 2 Allen 1978, p. 25

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 17

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 19, 20

- 1 2 3 Allen 1978, pp. 26, 27

- 1 2 3 Clackson & Horrocks 2007, p. 190

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 12, 13

- ↑ Levy, p. 150

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 45, 46

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 35–37

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 34, 35

- ↑ Lloyd 1987, p. 80

- 1 2 Lloyd 1987, p. 81

- 1 2 3 Allen 1978, pp. 30, 31

- ↑ Lloyd 1987, p. 84

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 27–30

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 23–25

- ↑ Allen & Greenough 2001, §10d

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 71–73

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 33

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 33, 34

- ↑ Sihler 1995, p. 174, §176 a: allophones of l in Latin

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 37–40

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 40–42

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 11

- 1 2 Allen 1978, p. 42

- 1 2 Allen 1978, pp. 15, 16

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 45

- ↑ Allen & Greenough, §1a

- 1 2 Clackson & Horrocks 2007, p. 96

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 15

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 23

- ↑ Sturtevant 1920, pp. 115–116

- ↑ Allen & Greenough 2001, §6d, 11c

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 47–49

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 51

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 51, 52

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 52

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 56

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 59

- ↑ Clackson 2008, p. 77

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 55, 56

- ↑ Ward 1962

- ↑ Clackson & Horrocks 2007, pp. 273, 274

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 65

- ↑ Sihler 2008, p. 174.

- ↑ Allen 2004, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Fortson 2004, p. 254

- ↑ Sturtevant 1920, pp. 207–218

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 83

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 87

- ↑ Allen & Greenough 2001, §11

- 1 2 Allen et al.

- 1 2 3 4 Allen 1978, pp. 89–92

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 86

- ↑ Allen & Greenough 2001, p. 400, section 612 e, f

- ↑ Gor example, Henri Estienne's Dictionarium, seu Latinae linguae thesaurus (1531)

- ↑ Gilbert 1939

- ↑ Frederick Brittain, Latin in Church; the history of its pronunciation, 1955

- 1 2 3 Liber Usualis, p. xxxviij

- ↑ Introduction to the Liber Usualis

- ↑ Robinson, Ray (1993). Up front!: becoming the complete choral conductor. p. 192. ISBN 9780911318197.

Not all authorities agree that s between vowels in Church Latin should be voiced. Of the sources cited in the bibliography, Hines, May/Tolin and Wall prefer the voiced s

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 108

- ↑ Liber Usualis, p. xxxvj

- ↑ Allen 1978, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Allen 1978, p. 119

- 1 2 Pope 1952, chapter 6, §4

Bibliography

- Alkire, Ti; Rosen, Carol (2010). Romance Languages: A Historical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521889155.

- Allen, William Sidney (1978) [1965]. Vox Latina—a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37936-9.

- Allen, William Sidney (1987). Vox Graeca: The Pronunciation of Classical Greek. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521335553.

- Allen, Joseph A.; Greenough, James B. (2001) [1903]. Mahoney, Anne, ed. New Latin Grammar for Schools and Colleges. Newburyport, Massachusetts: R. Pullins Company. ISBN 1-58510-042-0.

- Brittain, Frederick (1955). Latin in Church. The History of its Pronunciation (2nd ed.). Mowbray.

- Clackson, James; Horrocks, Geoffrey (2007). The Blackwell History of the Latin Language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-6209-8.

- Clackson, James (2008). "Latin". In Roger D. Woodward. The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68495-8.

- Gilbert, Allan H (June 1939). "Mock Accents in Renaissance and Modern Latin". Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. 54 (2): 608–610. doi:10.2307/458579.

- Hayes, Bruce (1995). Metrical stress theory: principles and case studies. University of Chicago. ISBN 9780226321042.

- Levy, Harry L. (1989). A Latin Reader for Colleges. University of Chicago Pressref=harv.

- Lloyd, Paul M. (1987). From Latin to Spanish. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87169-173-6.

- Neidermann, Max (1945) [1906]. Précis de phonétique historique du latin (2 ed.). Paris.

- McCullagh, Matthew (2011). "The Sounds of Latin: Phonology". In James Clackson. A Companion to the Latin Language. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1405186056.

- Pekkanen, Tuomo (1999). Ars grammatica—Latinan kielioppi (in Finnish and Latin) (3rd-6th ed.). Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. ISBN 951-570-022-1.

- Pope Pius X (November 22, 1903). "Tra le Sollecitudini". Rome, Italy: Adoremus. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Pope, M. K. (1952) [1934]. From Latin to Modern French with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman (revised ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508345-8.

- Smith, Jane Stuart (2004). Phonetics and Philology: Sound Change in Italic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925773-6.

- Sturtevant, Edgar Howard (1920). The pronunciation of Greek and Latin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ward, Ralf L. (June 1962). "Evidence For The Pronunciation Of Latin". The Classical World. 55 (9): 273–275. JSTOR 4344896. doi:10.2307/4344896.

- Wingo, E. Otha (1972). Latin Punctuation in the Classical Age. De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-9027923233.

External links

- phonetica latinæ: Classical and ecclesiastical Latin pronunciation with audio examples

- "Ecclesiastical Latin". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1910.

- Lord, Frances Ellen (2007) [1894]. The Roman Pronunciation of Latin: Why we use it and how to use it. Gutenberg Project.