Gothic architecture

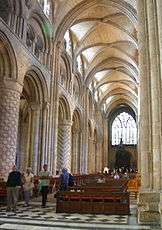

Gothic architecture an architectural style that flourished in Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. Originating in 12th century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture was known during the period as Opus Francigenum ("French work") with the term Gothic first appearing during the later part of the Renaissance. Its characteristics include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault (which evolved from the joint vaulting of Romanesque architecture) and the flying buttress. Gothic architecture is most familiar as the architecture of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe. It is also the architecture of many castles, palaces, town halls, guild halls, universities and to a less prominent extent, private dwellings, such as dorms and rooms.

It is in the great churches and cathedrals and in a number of civic buildings that the Gothic style was expressed most powerfully, its characteristics lending themselves to appeals to the emotions, whether springing from faith or from civic pride. A great number of ecclesiastical buildings remain from this period, of which even the smallest are often structures of architectural distinction while many of the larger churches are considered priceless works of art and are listed with UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. For this reason a study of Gothic architecture is often largely a study of cathedrals and churches.

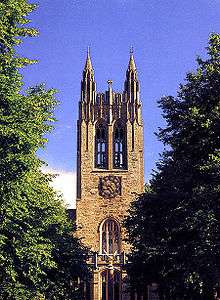

A series of Gothic revivals began in mid-18th century England, spread through 19th century Europe and continued, largely for ecclesiastical and university structures, into the 20th century.

Terminology

Unlike with past and future styles of art, like the Carolingian style as noted by French art historian Louis Grodecki in his work Gothic Architecture, Gothic's lack of a definite historical or geographic nexus results in a weak concept of what truly is Gothic. This is further compounded by the fact that the technical, ornamentation, and formal features of Gothic are not entirely unique to it. Though modern historians have invariably accepted the conventional use of "Gothic" as a label, even in formal analysis processes due to a longstanding tradition of doing so, the definition of "Gothic" has historically varied wildly.[1]

The term "Gothic architecture" originated as a pejorative description. Giorgio Vasari used the term "barbarous German style" in his 1550 Lives of the Artists to describe what is now considered the Gothic style,[2] and in the introduction to the Lives he attributes various architectural features to "the Goths" whom he held responsible for destroying the ancient buildings after they conquered Rome, and erecting new ones in this style.[3] Vasari was not alone among 15th and 16th Italian writers, as Filarete and Giannozzo Manetti had also written scathing criticisms of the Gothic style, calling it a "barbaric prelude to the Renaissance." Vasari and company were writing at a time when many aspects and vocabulary pertaining to Classical architecture had been reasserted with the Renaissance in the late 15th and 16th centuries, and they had the perspective that the "maniera tedesca" or "maniera dei Goti" was the antithesis of this resurgent style leading to the continuation of this negative connotation in the 17th century.[1] François Rabelais, also of the 16th century, imagines an inscription over the door of his utopian Abbey of Thélème, "Here enter no hypocrites, bigots..." slipping in a slighting reference to "Gotz" and "Ostrogotz."[lower-alpha 1] Molière also made this note of the Gothic style in the 1669 poem La Gloire:[1]

(in French): "...fade goût des ornements gothiques, Ces monstres odieux de siècles ignorants, Que de la barbarie ont produit les torrents.."

(in English): "...the insipid taste of Gothic ornamentation, these odious monstrosities of an ignorant age, produced by the torrents of barbarism..."— Molière, La Gloire

In English 17th century usage, "Goth" was an equivalent of "vandal," a savage despoiler with a Germanic heritage, and so came to be applied to the architectural styles of northern Europe from before the revival of classical types of architecture. According to a 19th-century correspondent in the London Journal Notes and Queries:[4]

There can be no doubt that the term 'Gothic' as applied to pointed styles of ecclesiastical architecture was used at first contemptuously, and in derision, by those who were ambitious to imitate and revive the Grecian orders of architecture, after the revival of classical literature. Authorities such as Christopher Wren lent their aid in deprecating the old medieval style, which they termed Gothic, as synonymous with everything that was barbarous and rude.

The first movements that reevaluated medieval art took place in the 18th century,[1] even when the Académie Royale d'Architecture met in Paris on 21 July 1710 and, amongst other subjects, discussed the new fashions of bowed and cusped arches on chimneypieces being employed to "finish the top of their openings. The Academy disapproved of several of these new manners, which are defective and which belong for the most part to the Gothic."[5] Despite resistance in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the writings of Wilhelm Worringer, critics like Père Laugier, William Gilpin, August Wilhelm Schlegel and other critics began to give the term a more positive meaning. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe called Gothic the "deutsche Architektur" and the "embodiment of German genius," while some French writers like Camille Enlart instead nationalised it for France, dubbing it "architecture français." This second group made some of their claims using the chronicle of Burchard von Halle that tells of the Church of Bad Wimpfen's construction "opere francigeno," or "in the French style." Today, the term is defined with spatial observations and historical and ideological information.[1]

Definition and scope

Since the studies of the 18th century, many have attempted to define the Gothic style using a list of characteristic features, principally with the pointed arch,[lower-alpha 2] the vaulting supported by intersecting arches, and the flying buttress. Eventually, historians composed a fairly large list of those features that were alien to both early medieval and Classical arts that includes piers with groups of colonettes, pinnacles, gables, rose windows, and openings broken into many different lancet-shaped sections. Certain combinations thereof have been singled out for identifying regional or national sub-styles of Gothic or to follow the evolution of the style. From this emerge labels such as Flamboyant, Rayonnant, and the English Perpendicular because of the observation of components like window tracery and pier moldings. This idea, dubbed by Paul Frankl as "componential," had also occurred to mid 19th century writers such as Arcisse de Caumont, Robert Willis and Franz Mertens.[1][lower-alpha 3]

As an architectural style, Gothic developed primarily in ecclesiastical architecture, and its principles and characteristic forms were applied to other types of buildings. Buildings of every type were constructed in the Gothic style, with evidence remaining of simple domestic buildings, elegant town houses, grand palaces, commercial premises, civic buildings, castles, city walls, bridges, village churches, abbey churches, abbey complexes and large cathedrals.

The greatest number of surviving Gothic buildings are churches. These range from tiny chapels to large cathedrals, and although many have been extended and altered in different styles, a large number remain either substantially intact or sympathetically restored, demonstrating the form, character and decoration of Gothic architecture. The Gothic style is most particularly associated with the great cathedrals of Northern France, the Low Countries, England and Spain, with other fine examples occurring across Europe.

Influences

Political

The roots of the Gothic style lie in those towns that, since the 11th century, had been enjoying increased prosperity and growth, began to experience more and more freedom from traditional feudal authority.[7] At the end of the 12th century, Europe was divided into a multitude of city states and kingdoms. The area encompassing modern Germany, southern Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria, Slovakia, Czech Republic and much of northern Italy (excluding Venice and Papal State) was nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, but local rulers exercised considerable autonomy under the system of Feudalism. France, Denmark, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, Scotland, Castile, Aragon, Navarre, Sicily and Cyprus were independent kingdoms, as was the Angevin Empire, whose Plantagenet kings ruled England and large domains in what was to become modern France.[lower-alpha 4] Norway came under the influence of England, while the other Scandinavian countries and Poland were influenced by trading contacts with the Hanseatic League. Angevin kings brought the Gothic tradition from France to Southern Italy, while Lusignan kings introduced French Gothic architecture to Cyprus. Gothic art is sometimes viewed as the art of the era of feudalism but also as being connected to change in medieval social structure, as the Gothic style of architecture seemed to parallel the beginning of the decline of feudalism.[8] Nevertheless, the influence of the established feudal elite can be seen in the Chateaux of French lords and in those churches sponsored by feudal lords.[9]

Throughout Europe at this time there was a rapid growth in trade and an associated growth in towns,[10][11] and they would come to be predominate in Europe by the end of the 13th century.[9] Germany and the Low Countries had large flourishing towns that grew in comparative peace, in trade and competition with each other or united for mutual weal, as in the Hanseatic League. Civic building was of great importance to these towns as a sign of wealth and pride. England and France remained largely feudal and produced grand domestic architecture for their kings, dukes and bishops, rather than grand town halls for their burghers. Viollet-le-Duc contended that the blossoming of the Gothic style came about as a result of growing freedoms in construction professions.[9]

Religious

The geographical expanse of the Gothic style is analogous to that of the Catholic Church, which prevailed across Europe at this time and influenced not only faith but also wealth and power.[9] Bishops were appointed by the feudal lords (Kings, Dukes, and other landowners) and they often ruled as virtual princes over large estates. The early Medieval periods had seen a rapid growth in monasticism, with several different orders being prevalent and spreading their influence widely. Foremost were the Benedictines whose great abbey churches vastly outnumbered any others in France and England. A part of their influence was that towns developed around them and they became centers of culture, learning and commerce. The Cluniac and Cistercian Orders were prevalent in France, the great monastery at Cluny having established a formula for a well planned monastic site which was then to influence all subsequent monastic building for many centuries. In the 13th century St. Francis of Assisi established the Franciscans, a mendicant order. The Dominicans, another mendicant order founded during the same period but by St. Dominic in Toulouse and Bologna, were particularly influential in the building of Italy's Gothic churches.[11]

The primary use of the Gothic style is in religious structures, naturally leading it to an association with the Church and it is considered to be one of the most formal and coordinated forms of the physical church, thought of as being the physical residence of God on Earth. According to Hans Sedlmayr, it was "even the considered the temporal image of Paradise, of the New Jerusalem." The horizontal and vertical scope of the Gothic church, filled with the light thought of as a symbol of the grace of God admitted into the structure via the style's iconic windows are among the very best examples of Christian architecture. Grodecki's Gothic Architecture also notes that the glass pieces of various colors that make up those windows have been compared to "precious stones encrusting the walls of the New Jerusalem," and that "the numerous towers and pinnacles evoke similar structures that appear in the visions of Saint John." Another idea, held by Georg Dehio and Erwin Panofsky, is that the designs of Gothic followed the current theological scholastic thought.[12] The PBS show NOVA explored the influence of the Holy Bible in the dimensions and design of some cathedrals.[13]

Geographic

From the 10th to the 13th century, Romanesque architecture had become a pan-European style and manner of construction, affecting buildings in countries as far apart as Ireland and Croatia, and Sweden and Sicily. The same wide geographic area was then affected by the development of Gothic architecture, but the acceptance of the Gothic style and methods of construction differed from place to place, as did the expressions of Gothic taste. The proximity of some regions meant that modern country borders did not define divisions of style. On the other hand, some regions such as England and Spain produced defining characteristics rarely seen elsewhere, except where they have been carried by itinerant craftsmen, or the transfer of bishops. Many different factors like geographical/geological, economic, social, or political situations caused the regional differences in the great abbey churches and cathedrals of the Romanesque period that would often become even more apparent in the Gothic. For example, studies of the population statistics reveals disparities such as the multitude of churches, abbeys, and cathedrals in northern France while in more urbanised regions construction activity of a similar scale was reserved to a few important cities. Such an example comes from Roberto López, wherein the French city of Amiens was able to fund its architectural projects whereas Cologne could not because of the economic inequality of the two.[14] This wealth, concentrated in rich monasteries and noble families, would eventually spread certain Italian, Catalan, and Hanseatic bankers.[15] This would be amended when the economic hardships of the 13th century were no longer felt, allowing Normandy, Tuscany, Flanders, and the southern Rhineland to enter into competition with France.[16]

The local availability of materials affected both construction and style. In France, limestone was readily available in several grades, the very fine white limestone of Caen being favoured for sculptural decoration. England had coarse limestone and red sandstone as well as dark green Purbeck marble which was often used for architectural features. In Northern Germany, Netherlands, northern Poland, Denmark, and the Baltic countries local building stone was unavailable but there was a strong tradition of building in brick. The resultant style, Brick Gothic, is called Backsteingotik in Germany and Scandinavia and is associated with the Hanseatic League. In Italy, stone was used for fortifications, so brick was preferred for other buildings. Because of the extensive and varied deposits of marble, many buildings were faced in marble, or were left with undecorated façade so that this might be achieved at a later date. The availability of timber also influenced the style of architecture, with timber buildings prevailing in Scandinavia. Availability of timber affected methods of roof construction across Europe. It is thought that the magnificent hammerbeam roofs of England were devised as a direct response to the lack of long straight seasoned timber by the end of the Medieval period, when forests had been decimated not only for the construction of vast roofs but also for ship building.[10][17]

Possible Eastern influence

The pointed arch, one of the defining attributes of Gothic, was earlier incorporated into Islamic architecture following the Islamic conquests of Roman Syria and the Sassanid Empire in the 7th century.[10] The pointed arch and its precursors had been employed in Late Roman and Sassanian architecture; within the Roman context, evidenced in early church building in Syria and occasional secular structures, like the Roman Karamagara Bridge; in Sassanid architecture, in the parabolic and pointed arches employed in palace and sacred construction.[18][19]

Increasing military and cultural contacts with the Muslim world, including the Norman conquest of Islamic Sicily in 1090, the Crusades (beginning 1096), and the Islamic presence in Spain, may have influenced Medieval Europe's adoption of the pointed arch, although this hypothesis remains controversial.[20][21] Certainly, in those parts of the Western Mediterranean subject to Islamic control or influence, rich regional variants arose, fusing Romanesque and later Gothic traditions with Islamic decorative forms, for example in Monreale and Cefalù Cathedrals, the Alcázar of Seville, and Teruel Cathedral.[22]

A number of scholars have cited the Armenian Cathedral of Ani, completed 1001 or 1010, as a possible influence on the Gothic, especially due to its use of pointed arches and cluster piers.[23][24][25][26] However, other scholars such as Armenian art historian Sirarpie Der Nersessian, who rejected this notion as she argued that the pointed arches did not serve the same function of supporting the vault.[27] Furthermore, the website Virtual Ani (now defunct) wrote that there is "no evidence to indicate that there was a connection between Armenian architecture and the development of the Gothic style in Western Europe."[28] Regardless, Lucy Der Manuelian, author of Ani: The Fabled Capital of Armenia, contends that some Armenians (historically documented as being in Western Europe in the Middle Ages)[29] could have brought the knowledge and technique employed at Ani to the west.[30]

The view held by the majority of scholars however is that the pointed arch evolved naturally in Western Europe as a structural solution to a technical problem, with evidence for this being its use as a stylistic feature in Romanesque French and English churches.[20]

History

The Gothic style originated in the Ile-de-France region of France at the Romanesque era in the first half of the 12th century,[31] at the Cathedral of Sens (1130–62) and Abbey of St-Denis (c. 1130–40 and 1140–44),[32] and did not immediately supersede it.[31] An example of this lack clean break is the blossoming of the Late Romanesque (German: Spätromanisch) in the Holy Roman Empire under the Hohenstaufens and Rhineland while the Gothic style spread into England and France in the 12th century.[16]

Romanesque tradition

By the 12th century, Romanesque architecture, termed Norman Gothic in England,[33] was established throughout Europe and provided the basic architectural forms and units that were to remain in evolution throughout the Medieval period. The important categories of building: the cathedral, parish church, monastery, castle, palace, great hall, gatehouse, and civic building had been established in the Romanesque period.

Many architectural features that are associated with Gothic architecture had been developed and used by the architects of Romanesque buildings, but not fully exploited.[34] These include ribbed vaults, buttresses, clustered columns, ambulatories, wheel windows, spires, stained glass windows, and richly carved door tympana.[35] These features, namely the rib vault and the pointed arch, had been used since the late 11th century in Southern Italy, Durham, and Picardy.[34]

It was principally the widespread introduction of a single feature, the pointed arch, which was to bring about the change that separates Gothic from Romanesque. The technological change permitted a stylistic change which broke the tradition of massive masonry and solid walls penetrated by small openings, replacing it with a style where light appears to triumph over substance. With its use came the development of many other architectural devices, previously put to the test in scattered buildings and then called into service to meet the structural, aesthetic and ideological needs of the new style. These include the flying buttresses, pinnacles and traceried windows which typify Gothic ecclesiastical architecture.[10]

Transition from Romanesque to Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture did not emerge from a dying Romanesque tradition, but from a Romanesque style at the height of its popularity, and it would supplant it for many years.[31] This shift in style beginning in the mid 12th century came about in an environment of much intellectual and political development as the Catholic Church began to grow into a very powerful political entity.[36] Another transition made by Gothic was the move from the rural monasteries of the Romanesque into urban environments with new Gothic churches built in wealthy cities by secular clergy knowing full well the growing unity and power of the Church.[37] The characteristic forms that were to define Gothic architecture grew out of Romanesque architecture and developed at several different geographic locations, as the result of different influences and structural requirements. While barrel vaults and groin vaults are typical of Romanesque architecture, ribbed vaults were used in many later Romanesque churches. The first examples of the ribbed vault, atop the thick walls of the Romanesque church, appeared at the same time in England and Normandy at Durham Cathedral (from 1093-before 1110), Winchester, Peterborough and Gloucester, Lessay Abbey's choir and transept, Duclair and Church of Saint Paul in Rouen.[29] The geometric ornamentation borne by the moldings of some of these vaults attests to the want for more decoration, and this would be answered later by architects working in Ile-de-France, Valois, and Vexin.[38] Later French projects from 1125 to 1135 show the lightening up of vaults contoured in a single or double convex profile and thinner walls. The Abbey of Notre Dame de Morienval in Valois is one such example, with vaulting covering trapezoidal around an ambulatory, lightened supports and vaulting that would be copied at Sens Cathedral and Suger's Basilica of Saint-Denis. While Norman architects would also participate in this development, the Romanesque in the Holy Roman Empire and Lombardy would remain the same with only little experimentation with vaulting. Two more features of Norman Romanesque, the wall buttress and the thick "double shell" wall at window height, were to later play a role in the birth of Gothic architecture. This double wall, a convenient way to reach the windows, hosted a passageway of recycled space that first appeared in the transepts of Bernay and Jumièges Abbey around 1040-50. This window-level passageway gave an illusion of weightlessness, inspired Noyon Cathedral, and would affect the entirety of the Gothic form of art.[39]

Other characteristics of early Gothic architecture, such as vertical shafts, clustered columns, compound piers, plate tracery and groups of narrow openings had evolved during the Romanesque period. The west front of Ely Cathedral exemplifies this development. Internally the three tiered arrangement of arcade, gallery and clerestory was established. Interiors had become lighter with the insertion of more and larger windows.

All modern historians agree that Suger's St.-Denis and Henri Sanglier's Sens Cathedral exemplify the development of Norman Romanesque architectural features into the Gothic through a new ordering of interior space, accented by support from supports freestanding and otherwise, and the shift of emphasis from sheer size to admittance of light. Later additions or remodeling prevent the observation of either structure in the time of their construction, the original plan was nonetheless recreated the plans of each and, as Francis Salet points out, Sens (the older of the two) still uses a Romanesque plan with an ambulatory and no transept and echoes with its supports the old Norman alternations. Its three-story high pointed arcade, openings above the vaulting, and windows are not derived from Burgundy, but rather from the triple division present in Normandy and England. Even the sexpartite vaulting of Sens's nave is likely of Norman origin, though the presence of wall ribbing belies Burgundian influence in design. Sens would, in spite of its archaic Norman features, exert much influence. From Sens spread the shrinking or omitting of the transept, the sexpartite vault, alternating interior, and the three-story elevation of future churches.[40]

Abbot Suger

The beginning of the Gothic style is held by all modern historians to be in the first half of the 12th century at the Basilica of St Denis in the Ile-de-France,[40] the royal domain of the Capetian kings rich in industry and the wool trade,[41] because of the records he left during reconstruction of what he desired of this renovation, rather than the contemporary churches that explore some of the same ideas used at St. Denis.[37] Suger believed in the spiritual power of light and colour, following in the philosophy of the 3rd century pagan Dionysius the Areopagite, whose identity was fused with that of the patron saint of Paris, and leading him in the end to require large windows of stained glass.[lower-alpha 5] This new church also needed to be larger than the previous Carolingian building to allow a greater number of pilgrims to feast inside the church.[42] The solution, Suger found, was to make unprecedented use of the ribbed vault and the pointed arch. St. Denis's plan possesses some very irregular shapes in its bays, prompting its architect to build the arches first so that arches of different height had keystones at the same height. Next the infill was added, and this method was proven to both provide more visual stimulation and speed up construction.[34]

The choir and west front of the Abbey of Saint-Denis both became the prototypes for further building in the royal domain of northern France and in the Duchy of Normandy. Through the rule of the Angevin dynasty, the new style was introduced to England and spread throughout France, the Low Countries, Germany, Spain, northern Italy and Sicily.

Compared to Sens Cathedral, St.-Denis is more complex and innovative. There is an obvious difference between the enclosing ambulatory around the choir, dedicated 11 June 1144 in the presence of the King,[lower-alpha 6][11] and the pre-Suger narthex, or antenave, (1140) that is derived from pre-Romanesque Ottonian Westwerk, and it shows in the heavily molded cross-ribbing and multiple projecting colonnettes positioned directly under the volutes of the rib's archivolts.[44] However, in iconographical terms, the three portals display, for the first time, sculpture that is demonstrably no longer Romanesque.[40]

Spread

Even as the role of the monastic orders seemed to diminish in the dawn of the Gothic era, the orders still had their own parts to play in the spread of the Gothic style, also disproving the common evaluation of Romanesque as the rural monastic style and Gothic as the urban ecclesiastical style. Chief among early promoters of this style were the Benedictines in England, France, and Normandy. Gothic churches that can be associated with them include Durham Cathedral in England, the Abbey of St Denis, Vezelay Abbey, and Abbey of Saint-Remi in France. Later Benedictine projects (constructions and renovations), made possible by the continued prominence of the Benedictine order throughout the Middle Ages, include Reims's Abbey of Saint-Nicaise, Rouen's Abbey of Saint-Ouen, Abbey of St. Robert at La Chaise-Dieu, and the choir of Mont Saint-Michel in France; English examples are Westminster Abbey, and the reconstruction of the Benedictine church at Canterbury. The Cistercians also had a hand in the spread of the Gothic style, first utilizing the Romanesque style for their monasteries since their inception as a reflection of their poverty, they became the total disseminators of the Gothic style as far east and south as Poland and Hungary.[45] Smaller orders, the Carthusians and Premonstratensians, also built some 200 churches (usually near cities),[46] but it was the mendicant orders, the Franciscans and Dominicans, who would most affect the change of art from the Romanesque to the Gothic in the 13th and 14th centuries. Of the military orders, the Knights Templar did not much contribute while the Teutonic Order spread Gothic art into Pomerania, East Prussia, and the Baltic region.[47]

Characteristics of the Gothic style

While many secular buildings exist from the Late Middle Ages, it is in the cathedrals and great churches that Gothic architecture displays its pertinent structures and characteristics to the fullest advantage. 19th century art historians and critics, used to the Baroque or Neoclassical works of the 17th and 18th centuries, were astounded by the soaring heights of a Gothic cathedral and made note of the extreme length compared to proportionally modest width and accentuating clusters of support colonnettes.[48] This emphasis on verticality and light was applied to an ecclesiastical building was achieved by the development of certain architectural features of the Gothic style that, when together, provided inventive solutions to various engineering problems. As Eugène Viollet-le-Duc observed, the Gothic cathedral, almost always laid out in a cruciform shape, was based on a logical skeleton of clustered columns, pointed ribbed vaults and flying buttresses arranged in a system of diagonal arches and arches enclosing the vault field that allows the outward thrust exerted by the groin vaults to be channeled from the walls and into specific points on a supporting mass. The result of this curvature in the vaults and arches of the church was the casting of indeterminable localised thrust that architects learned to counter with an opposing thrust in the form of the flying buttress and application of calculated weight via the pinnacle. This dynamic system of various constituent elements filling a certain role allowed for the slimming of previously massive walls or replacement thereof with windows.[6] Gothic churches were also very ornamented and highly decorated, serving as a Poor Man's Bible and a record of their construction in the stained glass windows that admit light into the church interior and some of the gargoyles. These structures, for centuries the principle landmark in a town, would then often be surmounted by one or more towers and pinnacles and perhaps tall spires.[10][49]

Pointed arch

One of the defining characteristics of Gothic architecture is the pointed (or ogival) arch, and it is used in nearly all places a vaulted shape might be called for structural or decorative consideration, like doorways, windows, arcades, and galleries. Gothic vaulting above spaces, regardless of size, is sometimes supported by richly moulded ribs. The constant use of the pointed arch in Gothic arches and tracery eventually led to the creation of the now extinct term "ogival architecture."[1]

The pointed arch is also a characteristic feature of Near Eastern pre-Islamic Sassanian architecture that was adopted in the 7th century by Islamic architecture and appears in structures like the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, and several structures of Norman Sicily. Then, it appeared in some Romanesque works in Italy (Cathedral of Modena) Burgundy (Autun Cathedral), later being mastered by Gothic architects for the cathedrals of Notre-Dame de Paris and Noyon Cathedral.[32] The majority view of scholars however is the idea that the pointed arch was a simultaneous and natural evolution in Western Europe as a solution to the problem of vaulting spaces of irregular plan, or to bring transverse vaults to the same height as diagonal vaults,[20][50] as evidenced by Durham Cathedral's nave aisles, built in 1093. Pointed arches also occur extensively in Romanesque decorative blind arcading, where semi-circular arches overlap each other in a simple decorative pattern and their points an accident in design.[50] In addition to being able to its applicability to rectangular or irregular shapes, the pointed arch channels weight onto the bearing piers or columns at a steep angle, enabling architects to raise vaults much higher than was possible in Romanesque architecture.[10] When used with other typical features of Gothic construction, a system of mutual independence in dispensing the immense weight of a Gothic cathedral's roof and vaulting emerges.[6]

Rows of pointed arches upon delicate shafts form a typical wall decoration known as blind arcading. Niches with pointed arches and containing statuary are a major external feature. The pointed arch lent itself to elaborate intersecting shapes which developed within window spaces into complex Gothic tracery forming the structural support of the large windows that are characteristic of the style.[17][35]

The ribbed vault, another key feature of the Gothic style, has a history just as colorful, having long been adapted for the Roman (Villa of Sette Bassi), Sassanian, Islamic (Abbas I's Mosque at Isfahan, Mosque of Cristo de la Luz), Romanesque (L'Hôpital-Saint-Blaise), and then Gothic styles.[32] Until the height of the Gothic era, few Western rib vaults matched the complexity of Islamic (mostly Moorish), beginning with experiments in Armenia and Georgia, from the 10th to the 13th centuries, such as ribbed domes (Ani Cathedral and Nikortsminda Cathedral), diagonal arches on a square field (Ani), and arches perpendicular to walls (Homoros Vank). However, the function of these vaults is entirely structural rather than decorative, as in Gothic cathedrals.[51] However, their indrect method of supporting the vault via its shoulders has been found at Casale Monferrato, Tour Guinette, and at a tower at Bayeux Cathedral. One reason for this perhaps is the record of economic and political exchange between some of western Europe and Armenia, which might explain the similarities between Armenian architecture and the ribbed vaults at San Nazzaro Sesia and at Lodi Vecchio in Lombardy and the Abbey of Saint Aubin in Angers. Ribbed vaults saw something of a golden age of development in the Anglo-Norman period, and led to the establishment of French Gothic and outlined many future Gothic solutions to the problem of support with buttresses.[52]

Height

A characteristic of Gothic church architecture is its height, both absolute and in proportion to its width, the verticality suggesting an aspiration to Heaven. A section of the main body of a Gothic church usually shows the nave as considerably taller than it is wide. In England the proportion is sometimes greater than 2:1, while the greatest proportional difference achieved is at Cologne Cathedral with a ratio of 3.6:1. The highest internal vault is at Beauvais Cathedral at 48 metres (157 ft).[10] The pointed arch, itself a suggestion of height, is appearance is characteristically further enhanced by both the architectural features and the decoration of the building.[49]

Verticality is emphasised on the exterior in a major way by the towers and spires, a characteristic of Gothic churches both great and small varying from church to church, and in a lesser way by strongly projecting vertical buttresses, by narrow half-columns called attached shafts which often pass through several storeys of the building, by long narrow windows, vertical mouldings around doors and figurative sculpture which emphasises the vertical and is often attenuated. The roofline, gable ends, buttresses and other parts of the building are often terminated by small pinnacles, Milan Cathedral being an extreme example in the use of this form of decoration. In Italy, the tower, if present, is almost always detached from the building, as at Florence Cathedral, and is often from an earlier structure. In France and Spain, two towers on the front is the norm. In England, Germany and Scandinavia this is often the arrangement, but an English cathedral may also be surmounted by an enormous tower at the crossing. Smaller churches usually have just one tower, but this may also be the case at larger buildings, such as Salisbury Cathedral or Ulm Minster in Ulm, Germany, completed in 1890 and possessing the tallest spire in the world,[53] slightly exceeding that of Lincoln Cathedral, the tallest spire that was actually completed during the medieval period, at 160 metres (520 ft).[54]

On the interior of the building attached shafts often sweep unbroken from floor to ceiling and meet the ribs of the vault, like a tall tree spreading into branches. The verticals are generally repeated in the treatment of the windows and wall surfaces. In many Gothic churches, particularly in France, and in the Perpendicular period of English Gothic architecture, the treatment of vertical elements in gallery and window tracery creates a strongly unifying feature that counteracts the horizontal divisions of the interior structure.[49]

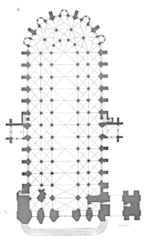

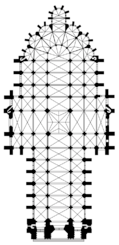

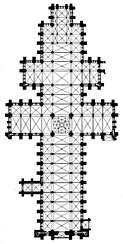

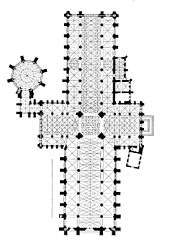

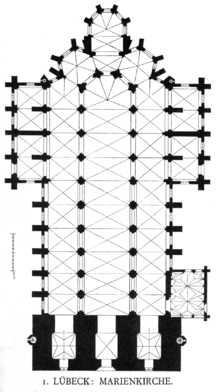

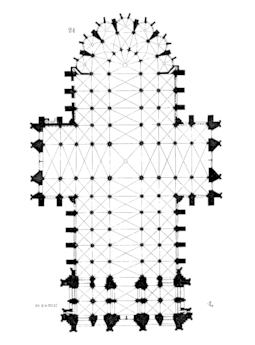

Plan

Most large Gothic churches and many smaller parish churches are of the Latin cross (or "cruciform") plan, with a long nave making the body of the church, a transverse arm called the transept and, beyond it, an extension which may be called the choir, chancel or presbytery. There are several regional variations on this plan.

The nave is generally flanked on either side by aisles, usually single, but sometimes double. The nave is generally considerably taller than the aisles, having clerestory windows which light the central space. Gothic churches of the Germanic tradition, like St. Stephen of Vienna, often have nave and aisles of similar height and are called Hallenkirche. In the South of France there is often a single wide nave and no aisles, as at Sainte-Marie in Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges.

In some churches with double aisles, like Notre Dame, Paris, the transept does not project beyond the aisles. In English cathedrals transepts tend to project boldly and there may be two of them, as at Salisbury Cathedral, though this is not the case with lesser churches.

The eastern arm shows considerable diversity. In England it is generally long and may have two distinct sections, both choir and presbytery. It is often square ended or has a projecting Lady Chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In France the eastern end is often polygonal and surrounded by a walkway called an ambulatory and sometimes a ring of chapels called a "chevet." While German churches are often similar to those of France, in Italy, the eastern projection beyond the transept is usually just a shallow apsidal chapel containing the sanctuary, as at Florence Cathedral.[10][35][49]

Another very characteristic feature of the Gothic style, domestic and ecclesiastical alike, is the division of interior space into individual cells according to the building's ribbing and vaults, regardless of whether or not the structure actually has a vaulted ceiling. This system of cells of varying size and shape juxtaposed in various patterns was again totally unique to antiquity and the Early Middle Ages and scholars, Frankl included, have emphasised the mathematical and geometric nature of this design. Frankl in particular thought of this layout as "creation by division" rather than the Romanesque's "creation by addition." Others, namely Viollet-le-Duc, Wilhelm Pinder, and August Schmarsow, instead proposed the term "articulated architecture."[55] The opposite theory as suggested by Henri Focillon and Jean Bony is of "spacial unification", or of the creation of an interior that is made for sensory overload via the interaction of many elements and perspectives.[56] Interior and exterior partitions, often extensively studied, have been found to at times contain features, such as thoroughfares at window height, that make the illusion of thickness. Additionally, the piers separating the isles eventually stopped being part of the walls but rather independent objects that jut out from the actual aisle wall itself.[57]

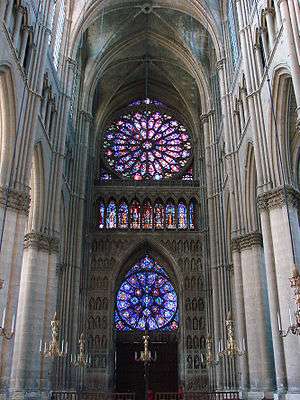

Light and windows

One of the most ubiquitous elements of Gothic architecture is the shrinking of the walls and inserting of large windows. Notables such as Viollet-le-Duc, Focillon, Aubert, and Max Dvořák contended that this one of the most universal features of the Gothic style. Yet another departure from the Romanesque style, windows grew in size as the Gothic style evolved, eventually almost eliminating all the wall-space as in Paris's Sainte-Chapelle, admitting immense amounts of light into the church. This expansive interior light has been a feature of Gothic cathedrals since their inception, and this is because of the function of space in a Gothic cathedral as a function of light that is very widely referred to in contemporary text.[12] The metaphysics of light in the Middle Ages led to clerical belief in its divinity and the importance of its display in holy settings. Much of this belief was based on the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius, a 6th-century mystic whose book, The Celestial Hierarchy, was popular among monks in France. Pseudo-Dionysius held that all light, even light reflected from metals or streamed through windows, was divine. To promote such faith, the abbot in charge of the Saint-Denis church on the north edge of Paris, the Abbot Suger, encouraged architects remodeling the building to make the interior as bright as possible.

Ever since the remodeled Basilica of Saint-Denis opened in 1144, Gothic architecture has featured expansive windows, such as at Sainte Chapelle, York Minster, Gloucester Cathedral. The increase in size between windows of the Romanesque and Gothic periods is related to the use of the ribbed vault, and in particular, the pointed ribbed vault which channeled the weight to a supporting shaft with less outward thrust than a semicircular vault. Walls did not need to be so weighty.[35][49]

A further development was the flying buttress which arched externally from the springing of the vault across the roof of the aisle to a large buttress pier projecting well beyond the line of the external wall. These piers were often surmounted by a pinnacle or statue, further adding to the downward weight, and counteracting the outward thrust of the vault and buttress arch as well as stress from wind loading.

The internal columns of the arcade with their attached shafts, the ribs of the vault and the flying buttresses, with their associated vertical buttresses jutting at right-angles to the building, created a stone skeleton. Between these parts, the walls and the infill of the vaults could be of lighter construction. Between the narrow buttresses, the walls could be opened up into large windows.[10]

Through the Gothic period, thanks to the versatility of the pointed arch, the structure of Gothic windows developed from simple openings to immensely rich and decorative sculptural designs. The windows were very often filled with stained glass which added a dimension of colour to the light within the building, as well as providing a medium for figurative and narrative art.[49]

Majesty

The façade of a large church or cathedral, often referred to as the West Front, is generally designed to create a powerful impression on the approaching worshipper, demonstrating both the might of God and the might of the institution that it represents. One of the best known and most typical of such façades is that of Notre Dame de Paris.

Central to the façade is the main portal, often flanked by additional doors. In the arch of the door, the tympanum, is often a significant piece of sculpture, most frequently Christ in Majesty and Judgment Day. If there is a central doorjamb or a trumeau, then it frequently bears a statue of the Madonna and Child. There may be much other carving, often of figures in niches set into the mouldings around the portals, or in sculptural screens extending across the façade.

Above the main portal there is generally a large window, like that at York Minster, or a group of windows such as those at Ripon Cathedral. In France there is generally a rose window like that at Reims Cathedral. Rose windows are also often found in the façades of churches of Spain and Italy, but are rarer elsewhere and are not found on the façades of any English Cathedrals. The gable is usually richly decorated with arcading or sculpture or, in the case of Italy, may be decorated with the rest of the façade, with polychrome marble and mosaic, as at Orvieto Cathedral.

The West Front of a French cathedral and many English, Spanish and German cathedrals generally have two towers, which, particularly in France, express an enormous diversity of form and decoration.[10][11] However some German cathedrals have only one tower located in the middle of the façade (such as Freiburg Münster).

Basic shapes of Gothic arches and stylistic character

The way in which the pointed arch was drafted and utilised developed throughout the Gothic period. There were fairly clear stages of development which did not progress at the same rate or in the same way in every country. Moreover, the names used to define various periods or styles within Gothic architecture differs from country to country. The work of art historians Hans R. Hahnloser and Robert Branner in studying manuscripts and architectural drawings showed that the use of geometric shapes and proportions in squares, circles, semi-circular shapes, and equilateral triangles, abandoned in the Renaissance, was a constant effort in the Middle Ages.[55]

Transverse arches, perpendicular to the upper level of the walls and hidden under gallery roofing, appeared circa 1100 at Durham Cathedral and at Cérisy-la-Forêt and are thought to have been used to facilitate roofing and the construction of wall buttressing, as there was no need to give any further support to already thick Romanesque walls.[39] Used at the nave of Durham and at Caen's Abbey of Saint-Trinité, this practice would also be used by Gothic architects at Saint-Germer-de-Fly Abbey and Laon Cathedral. Further application and refinement of this technique since the 11th century made the purpose of the transverse clearer, culminating in the late 12th century as architects used its gallery to buttress the upper echelons of a church.[39]

Lancet arch

The simplest shape is the long opening with a pointed arch known in England as the lancet. Lancet openings are often grouped, usually as a cluster of three or five. Lancet openings may be very narrow and steeply pointed. Lancet arches are typically defined as two-centered arches whose radii are larger than the arch's span.[58]

Salisbury Cathedral is famous for the beauty and simplicity of its Lancet Gothic, known in England as the Early English Style. York Minster has a group of lancet windows each fifty feet high and still containing ancient glass. They are known as the Five Sisters. These simple undecorated grouped windows are found at Chartres and Laon Cathedrals and are used extensively in Italy.[10][17]

Equilateral arch

Many Gothic openings are based upon the equilateral form. In other words, when the arch is drafted, the radius is exactly the width of the opening and the centre of each arch coincides with the point from which the opposite arch springs. This makes the arch higher in relation to its width than a semi-circular arch which is exactly half as high as it is wide.[10]

The Equilateral Arch gives a wide opening of satisfying proportion useful for doorways, decorative arcades and large windows.

The structural beauty of the Gothic arch means, however, that no set proportion had to be rigidly maintained. The Equilateral Arch was employed as a useful tool, not as a principle of design. This meant that narrower or wider arches were introduced into a building plan wherever necessity dictated. In the architecture of some Italian cities, notably Venice, semi-circular arches are interspersed with pointed ones.

The Equilateral Arch lends itself to filling with tracery of simple equilateral, circular and semi-circular forms. The type of tracery that evolved to fill these spaces is known in England as Geometric Decorated Gothic and can be seen to splendid effect at many English and French Cathedrals, notably Lincoln and Notre Dame in Paris. Windows of complex design and of three or more lights or vertical sections, are often designed by overlapping two or more equilateral arches.[17]

Flamboyant arch

The Flamboyant Arch is one that is drafted from four points, the upper part of each main arc turning upwards into a smaller arc and meeting at a sharp, flame-like point. These arches create a rich and lively effect when used for window tracery and surface decoration. The form is structurally weak and has very rarely been used for large openings except when contained within a larger and more stable arch. It is not employed at all for vaulting.[10]

Some of the most beautiful and famous traceried windows of Europe employ this type of tracery. It can be seen at St Stephen's in Vienna, Sainte Chapelle in Paris, at the Cathedrals of Limoges and Rouen in France. In England the most famous examples are the West Window of York Minster with its design based on the Sacred Heart, the extraordinarily rich nine-light East Window at Carlisle Cathedral and the exquisite East window of Selby Abbey.[17][35]

Doorways surmounted by Flamboyant mouldings are very common in both ecclesiastical and domestic architecture in France. They are much rarer in England. A notable example is the doorway to the Chapter Room at Rochester Cathedral.[10][17]

The style was much used in England for wall arcading and niches. Prime examples in are in the Lady Chapel at Ely, the Screen at Lincoln and externally on the façade of Exeter Cathedral. In German and Spanish Gothic architecture it often appears as openwork screens on the exterior of buildings. The style was used to rich and sometimes extraordinary effect in both these countries, notably on the famous pulpit in Vienna Cathedral.[11]

Depressed arch

The depressed or four-centred arch is much wider than its height and gives the visual effect of having been flattened under pressure. Its structure is achieved by drafting two arcs which rise steeply from each springing point on a small radius and then turn into two arches with a wide radius and much lower springing point.[10]

This type of arch, when employed as a window opening, lends itself to very wide spaces, provided it is adequately supported by many narrow vertical shafts. These are often further braced by horizontal transoms. The overall effect produces a grid-like appearance of regular, delicate, rectangular forms with an emphasis on the perpendicular. It is also employed as a wall decoration in which arcade and window openings form part of the whole decorative surface.

The style, known as Perpendicular, that evolved from this treatment is specific to England, although very similar to contemporary Spanish style in particular, and was employed to great effect through the 15th century and first half of the 16th as Renaissance styles were much slower to arrive in England than in Italy and France.[10]

It can be seen notably at the East End of Gloucester Cathedral where the East Window is said to be as large as a tennis court. There are three very famous royal chapels and one chapel-like Abbey which show the style at its most elaborate: King's College Chapel, Cambridge; St George's Chapel, Windsor; Henry VII's Chapel at Westminster Abbey and Bath Abbey.[17] However very many simpler buildings, especially churches built during the wool boom in East Anglia, are fine examples of the style.

Symbolism and ornamentation

The Gothic cathedral represented the universe in microcosm and each architectural concept, including the loftiness and huge dimensions of the structure, were intended to convey a theological message: the great glory of God. The building becomes a microcosm in two ways. Firstly, the mathematical and geometrical nature of the construction is an image of the orderly universe, in which an underlying rationality and logic can be perceived.

Secondly, the statues, sculptural decoration, stained glass and murals incorporate the essence of creation in depictions of the Labours of the Months and the Zodiac[lower-alpha 8] and sacred history from the Old and New Testaments and Lives of the Saints, as well as reference to the eternal in the Last Judgment and Coronation of the Virgin.

The decorative schemes usually incorporated Biblical stories, emphasizing visual typological allegories between Old Testament prophecy and the New Testament.[11]

Many churches were very richly decorated, both inside and out. Sculpture and architectural details were often bright with coloured paint of which traces remain at the Cathedral of Chartres. Wooden ceilings and panelling were usually brightly coloured. Sometimes the stone columns of the nave were painted, and the panels in decorative wall arcading contained narratives or figures of saints. These have rarely remained intact, but may be seen at the Chapterhouse of Westminster Abbey.[17]

Some important Gothic churches could be severely simple such as the Basilica of Mary Magdalene in Saint-Maximin, Provence where the local traditions of the sober, massive, Romanesque architecture were still strong.

Regional differences

Wherever Gothic architecture is found, it is subject to local influences, and frequently the influence of itinerant stonemasons and artisans, carrying ideas between cities and sometimes between countries. Certain characteristics are typical of particular regions and often override the style itself, appearing in buildings hundreds of years apart.

France

The distinctive characteristic of French cathedrals, and those in Germany and Belgium that were strongly influenced by them, is their height and their impression of verticality. Each French cathedral tends to be stylistically unified in appearance when compared with an English cathedral where there is great diversity in almost every building. They are compact, with slight or no projection of the transepts and subsidiary chapels. The west fronts are highly consistent, having three portals surmounted by a rose window, and two large towers. Sometimes there are additional towers on the transept ends. The east end is polygonal with ambulatory and sometimes a chevette of radiating chapels. In the south of France, many of the major churches are without transepts and some are without aisles.[10]

England

The distinctive characteristic of English cathedrals is their extreme length, and their internal emphasis upon the horizontal, which may be emphasised visually as much or more than the vertical lines. Each English cathedral (with the exception of Salisbury) has an extraordinary degree of stylistic diversity, when compared with most French, German and Italian cathedrals. It is not unusual for every part of the building to have been built in a different century and in a different style, with no attempt at creating a stylistic unity. Unlike French cathedrals, English cathedrals sprawl across their sites, with double transepts projecting strongly and Lady Chapels tacked on at a later date, such as at Westminster Abbey. In the west front, the doors are not as significant as in France, the usual congregational entrance being through a side porch. The West window is very large and never a rose, which are reserved for the transept gables. The west front may have two towers like a French Cathedral, or none. There is nearly always a tower at the crossing and it may be very large and surmounted by a spire. The distinctive English east end is square, but it may take a completely different form. Both internally and externally, the stonework is often richly decorated with carvings, particularly the capitals.[10][17]

Germany, Poland and the Czech lands

Romanesque architecture in Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic (earlier called Bohemia) is characterised by its massive and modular nature. This characteristic is also expressed in the Gothic architecture of Central Europe in the huge size of the towers and spires, often projected, but not always completed.[lower-alpha 9] Gothic design in Germany and Czech lands, generally follows the French formula, but the towers are much taller and, if complete, are surmounted by enormous openwork spires that are a regional feature. Because of the size of the towers, the section of the façade between them may appear narrow and compressed. The distinctive character of the interior of German Gothic cathedrals is their breadth and openness. This is the case even when, as at Cologne, they have been modelled upon a French cathedral. German and Czech cathedrals, like the French, tend not to have strongly projecting transepts. There are also many hall churches (Hallenkirchen) without clerestory windows.[10][49] In contrast to the Gothic designs found in western German and Czech areas, which followed the French patterns, Brick Gothic was particularly prevalent in Poland and northern Germany. The Polish gothic architecture is characterised by its utilitarian nature, with very limited use of sculpture and heavy exterior design.

Spain and Portugal

The distinctive characteristic of Gothic cathedrals of the Iberian Peninsula is their spatial complexity, with many areas of different shapes leading from each other. They are comparatively wide, and often have very tall arcades surmounted by low clerestories, giving a similar spacious appearance to the Hallenkirche of Germany, as at the Church of the Batalha Monastery in Portugal. Many of the cathedrals are completely surrounded by chapels. Like English cathedrals, each is often stylistically diverse. This expresses itself both in the addition of chapels and in the application of decorative details drawn from different sources. Among the influences on both decoration and form are Islamic architecture and, towards the end of the period, Renaissance details combined with the Gothic in a distinctive manner. The West front, as at Leon Cathedral, typically resembles a French west front, but wider in proportion to height and often with greater diversity of detail and a combination of intricate ornament with broad plain surfaces. At Burgos Cathedral there are spires of German style. The roofline often has pierced parapets with comparatively few pinnacles. There are often towers and domes of a great variety of shapes and structural invention rising above the roof.[10]

Crown of Aragon

In Crown of Aragon and the territories under its influence (Aragon, Catalonia, Northern Catalonia in France, the Balearic Islands, the Valencian Country, among others in the Italian islands), the Gothic style suppressed the transept and made the aisle almost as high as the main nave, allowing it to create very wide spaces, with few ornaments; it is called Catalan Gothic style (different than the Kingdom of Castile or French style).

The most important samples of Catalan Gothic style are the cathedrals of Girona, Barcelona, Perpignan and Palma (in Mallorca), the basilica of Santa Maria del Mar (in Barcelona), the Basílica del Pi (in Barcelona), and the church of Santa Maria de l'Alba in Manresa.

Italy

The distinctive characteristic of Italian Gothic is the use of polychrome decoration, both externally as marble veneer on the brick façade and also internally where the arches are often made of alternating black and white segments, and where the columns may be painted red, the walls decorated with frescoes and the apse with mosaic. The plan is usually regular and symmetrical, Italian cathedrals have few and widely spaced columns. The proportions are generally mathematically equilibrated, based on the square and the concept of "armonìa," and except in Venice where they loved flamboyant arches, the arches are almost always equilateral. Colours and moldings define the architectural units rather than blending them. Italian cathedral façades are often polychrome and may include mosaics in the lunettes over the doors. The façades have projecting open porches and occular or wheel windows rather than roses, and do not usually have a tower. The crossing is usually surmounted by a dome. There is often a free-standing tower and baptistry. The eastern end usually has an apse of comparatively low projection. The windows are not as large as in northern Europe and, although stained glass windows are often found, the favourite narrative medium for the interior is the fresco.[10]

Other Gothic buildings

Synagogues were commonly built in the Gothic style in Europe during the Medieval period. A surviving example is the Old New Synagogue in Prague built in the 13th century.

The Palais des Papes in Avignon is the best complete large royal palace, alongside the Royal palace of Olite, built during the 13th and 14th centuries for the kings of Navarre. The Malbork Castle built for the master of the Teutonic order is an example of Brick Gothic architecture. Partial survivals of former royal residences include the Doge's Palace of Venice, the Palau de la Generalitat in Barcelona, built in the 15th century for the kings of Aragon, or the famous Conciergerie, former palace of the kings of France, in Paris.

_-_13.jpg)

Secular Gothic architecture can also be found in a number of public buildings such as town halls, universities, markets or hospitals. The Gdańsk, Wrocław and Stralsund town halls are remarkable examples of northern Brick Gothic built in the late 14th centuries. The Belfry of Bruges or Brussels Town Hall, built during the 15th century, are associated to the increasing wealth and power of the bourgeoisie in the late Middle Ages; by the 15th century, the traders of the trade cities of Burgundy had acquired such wealth and influence that they could afford to express their power by funding lavishly decorated buildings of vast proportions. This kind of expressions of secular and economic power are also found in other late mediaeval commercial cities, including the Llotja de la Seda of Valencia, Spain, a purpose built silk exchange dating from the 15th century, in the partial remains of Westminster Hall in the Houses of Parliament in London, or the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, Italy, a 13th-century town hall built to host the offices of the then prosperous republic of Siena. Other Italian cities such as Florence (Palazzo Vecchio), Mantua or Venice also host remarkable examples of secular public architecture.

By the late Middle Ages university towns had grown in wealth and importance as well, and this was reflected in the buildings of some of Europe's ancient universities. Particularly remarkable examples still standing nowadays include the Collegio di Spagna in the University of Bologna, built during the 14th and 15th centuries; the Collegium Carolinum of the University of Prague in Bohemia; the Escuelas mayores of the University of Salamanca in Spain; the chapel of King's College, Cambridge; or the Collegium Maius of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland.

In addition to monumental secular architecture, examples of the Gothic style in private buildings can be seen in surviving medieval portions of cities across Europe, above all the distinctive Venetian Gothic such as the Ca' d'Oro. The house of the wealthy early 15th century merchant Jacques Coeur in Bourges, is the classic Gothic bourgeois mansion, full of the asymmetry and complicated detail beloved of the Gothic Revival.[59]

Other cities with a concentration of secular Gothic include Bruges and Siena. Most surviving small secular buildings are relatively plain and straightforward; most windows are flat-topped with mullions, with pointed arches and vaulted ceilings often only found at a few focal points. The country-houses of the nobility were slow to abandon the appearance of being a castle, even in parts of Europe, like England, where defence had ceased to be a real concern. The living and working parts of many monastic buildings survive, for example at Mont Saint-Michel.

Exceptional works of Gothic architecture can also be found on the islands of Sicily and Cyprus, in the walled cities of Nicosia and Famagusta. Also, the roofs of the Old Town Hall in Prague and Znojmo Town Hall Tower in the Czech Republic are an excellent example of late Gothic craftsmanship.

Gothic survival and revival

In 1663 at the Archbishop of Canterbury's residence, Lambeth Palace, a Gothic hammerbeam roof was built to replace that destroyed when the building was sacked during the English Civil War. Also in the late 17th century, some discrete Gothic details appeared on new construction at Oxford University and Cambridge University, notably on Tom Tower at Christ Church, Oxford, by Christopher Wren. It is not easy to decide whether these instances were Gothic survival or early appearances of Gothic revival.

Ireland was a focus for Gothic architecture in the 17th and 18th centuries. Derry Cathedral (completed 1633), Sligo Cathedral (c. 1730), and Down Cathedral (1790-1818) are notable examples. The term "Planter's Gothic" has been applied to the most typical of these.[60]

In England in the mid-18th century, the Gothic style was more widely revived, first as a decorative, whimsical alternative to Rococo that is still conventionally termed 'Gothick', of which Horace Walpole's Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill, is the familiar example.

Gothic Revival

The middle of the 19th century was a period marked by the restoration, and in some cases modification, of ancient monuments and the construction of Neo-Gothic edifices such as the nave of Cologne Cathedral and the Sainte-Clotilde of Paris as speculation of medieval architecture turned to technical consideration. London’s Palace of Westminster, St. Pancras railway station, New York’s Trinity Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedral are also famous examples of Gothic Revival buildings.[61]

While some credit for this new ideation can reasonably be assigned to German and English writers, namely Johannes Vetter, Franz Mertens, and Robert Willis respectively, this emerging style's champion was Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose lead was taken by archaeologists, historians, and architects like Jules Quicherat, Auguste Choisy, and Marcel Aubert.[6] In the last years of the 19th century, a trend among study in art history emerged in Germany that a building, as defined by Henri Focillon was an interpretation of space.[48] When applied to Gothic cathedrals, historians and architects used to the dimensions of 17th and 18th Baroque or Neoclassical structures, were astounded by the height and extreme length of the cathedrals compared to its proportionally modest width. Goethe, in the preceding century, was mesmerised by the space within a Gothic church and succeeding historians like Dehio, Walter Ueberwasser, Paul Frankl, and Maria Velte sought to rediscover the methodology used in their construction by making measurements and drawings of the buildings, and reading and making conjectures from documents and treaties pertaining to their construction.[55]

In England, partly in response to a philosophy propounded by the Oxford Movement and others associated with the emerging revival of 'high church' or Anglo-Catholic ideas during the second quarter of the 19th century, neo-Gothic began to become promoted by influential establishment figures as the preferred style for ecclesiastical, civic and institutional architecture. The appeal of this Gothic revival (which after 1837, in Britain, is sometimes termed Victorian Gothic), gradually widened to encompass "low church" as well as "high church" clients. This period of more universal appeal, spanning 1855–1885, is known in Britain as High Victorian Gothic.

The Houses of Parliament in London by Sir Charles Barry with interiors by a major exponent of the early Gothic Revival, Augustus Welby Pugin, is an example of the Gothic revival style from its earlier period in the second quarter of the 19th century. Examples from the High Victorian Gothic period include George Gilbert Scott's design for the Albert Memorial in London, and William Butterfield's chapel at Keble College, Oxford. From the second half of the 19th century onwards it became more common in Britain for neo-Gothic to be used in the design of non-ecclesiastical and non-governmental buildings types. Gothic details even began to appear in working-class housing schemes subsidised by philanthropy, though given the expense, less frequently than in the design of upper and middle-class housing.

In France, simultaneously, the towering figure of the Gothic Revival was Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who outdid historical Gothic constructions to create a Gothic as it ought to have been, notably at the fortified city of Carcassonne in the south of France and in some richly fortified keeps for industrial magnates. Viollet-le-Duc compiled and coordinated an Encyclopédie médiévale that was a rich repertory his contemporaries mined for architectural details. He effected vigorous restoration of crumbling detail of French cathedrals, including the Abbey of Saint-Denis and famously at Notre Dame de Paris, where many of whose most "Gothic" gargoyles are Viollet-le-Duc's. He taught a generation of reform-Gothic designers and showed how to apply Gothic style to modern structural materials, especially cast iron.

In Germany, the great cathedral of Cologne and the Ulm Minster, left unfinished for 600 years, were brought to completion, while in Italy, Florence Cathedral finally received its polychrome Gothic façade. New churches in the Gothic style were created all over the world, including Mexico, Argentina, Japan, Thailand, India, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii and South Africa.

As in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand utilised Neo-Gothic for the building of universities, a fine example being the University of Sydney by Edmund Blacket. In Canada, the Canadian Parliament Buildings in Ottawa designed by Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones with its huge centrally placed tower is influenced by Flemish Gothic buildings.

Although falling out of favour for domestic and civic use, Gothic for churches and universities continued into the 20th century with buildings such as Liverpool Cathedral, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York and São Paulo Cathedral, Brazil. The Gothic style was also applied to iron-framed city skyscrapers such as Cass Gilbert's Woolworth Building and Raymond Hood's Tribune Tower.

Post-Modernism in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has seen some revival of Gothic forms in individual buildings, such as the Gare do Oriente in Lisbon, Portugal and a finishing of the Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico.

See also

Medieval Gothic

- Castle

- Catenary arch

- Czech Gothic architecture

- English Gothic architecture

- French Gothic architecture

- Italian Gothic architecture

- List of Gothic architecture

- Medieval architecture

- Middle Ages in history

- Polish Gothic architecture

- Portuguese Gothic architecture

- Renaissance of the 12th century

- Spanish Gothic architecture

- Gothic secular and domestic architecture

Gothic architecture

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ "Gotz" is rendered as "Huns" in Thomas Urquhart's English translation.

- ↑ Grodecki notes that the term, ogive, is "today used to designate not the pointed arch but a rib that stretches diagonally across a vault." Note that "today" refers to 1977, the year of publishing for the edition of Gothic Architecture used in the writing of this article.

- ↑ Componential study has led to some complication as, for example, Laon Cathedral's façade neglects the pointed arch in favor of the rounded arch in its façade and would otherwise be excluded from the Gothic category while some Romanesque churches would be included.[6]

- ↑ Section from "L'art Gothique," translated into English: "England was one of the first regions to adopt, during the first half of the 12th century, the new Gothic architecture born in France. Historic relationships between the two countries played a determining role: in 1154, Henry II (1154–1189) became the first of the Anjou Plantagenet kings to ascend to the throne of England."

- ↑ In addition, Dionysius the Areopagite was also confused by a 9th century writer for the early Gaulish Christian martyr and first Bishop of Paris, Saint Denis.[42][43]

- ↑ Of this structure, all that remains is the choir.[40]

- ↑ While the engineering and construction of the dome of Florence Cathedral by Brunelleschi is often cited as one of the first works of the Renaissance, the octagonal plan, ribs and pointed silhouette were already determined in the 14th century.

- ↑ The Zodiac comprises a sequence of twelve constellations which appear overhead in the Northern Hemisphere at fixed times of year. In a rural community with neither clock nor calendar, these signs in the heavens were crucial in knowing when crops were to be planted and certain rural activities performed.

- ↑ Freiburg, Regensburg, Strasbourg, Vienna, Ulm, Cologne, Antwerp, Gdansk, Wroclaw.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grodecki 1977, p. 9.

- ↑ Vasari 1991, pp. 117, 527.

- ↑ Vasari, Brown & Maclehose 1907, pp. b. & 83.

- ↑ Notes and Queries, No. 9. 29 December 1849

- ↑ Fiske 1943, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Grodecki 1977, p. 11.

- ↑ Mitchell 1968, p. 9.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 20, 24.

- 1 2 3 4 Grodecki 1977, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 John Harvey, The Gothic World

- 1 2 Grodecki 1977, p. 20.

- ↑ Tiffany, Scott; Tinworth, Rob; Barako, Tristian (19 October 2010). "Building the Great Cathedrals". Nova. PBS.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 25-26.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 25.

- 1 2 Grodecki 1977, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Alec Clifton-Taylor, The Cathedrals of England

- ↑ Warren, John (1991). "Creswell's Use of the Theory of Dating by the Acuteness of the Pointed Arches in Early Muslim Architecture". Muqarnas. BRILL. 8: 59–65 (61–63). JSTOR 1523154. doi:10.2307/1523154.

- ↑ Petersen, Andrew (2002-03-11). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture at pp. 295-296. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- 1 2 3 Scott 2003, p. 113.

- ↑ Bony 1983, p. 17.

- ↑ Harvey, L. P. (1992). "Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500." Chicago : University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31960-1; Boswell, John (1978). Royal Treasure: Muslim Communities Under the Crown of Aragon in the Fourteenth Century. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02090-2.

- ↑ Lang 1980, p. 223: "With this experience behind him, it is not surprising that Trdat's creation of the Cathedral at Ani turned out to be a masterpiece. Even without its dome, the cathedral amazes the onlooker. Technically, it is far ahead of the contemporary Anglo-Saxon and Norman architecture of Europe. Already, pointed arches and clustered piers, whose appearance together is considered one of the hallmarks of mature Gothic architecture, are found in this remote corner of the Christian East."

- ↑ Kite, Stephen (September 2003). "'South Opposed to East and North': Adrian Stokes and Josef Strzygowski. A study in the aesthetics and historiography of Orientalism". Art History. 26 (4): 519.

To Near Eastern scholars the Armenian cathedral at Ani (989–1001), designed by Trdat (972–1036), seemed to anticipate Gothic.

- ↑ Stewart 1959, p. 80: "The most important examples of Armenian architecture are to be found at Ani, the capital, and the most important of these is the cathedral. [...] The most interesting features of this building are its pointed arches and vaults and the clustering or coupling of the columns in the Gothic manner."

- ↑ Talbot Rice 1972, p. 179: "The interior of Ani cathedral, a longitudinal stone building with pointed vaults and a central dome, built about 1001, is astonishingly Gothic in every detail, and numerous other equally close parallels could be cited."

- ↑ Garsoïan 2015, p. 300.

- ↑ "The Cathedral of Ani". virtualani.org. Virtual Ani. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016.

- 1 2 Grodecki 1977, p. 37.

- ↑ Der Manuelian 2001, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Raeburn 1980, p. 102.

- 1 2 3 Grodecki 1977, p. 36.

- ↑ Ross, David. "Gothic Architecture in England". Britainexpress.com. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- 1 2 3 Raeburn 1980, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nikolaus Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture.

- ↑ Raeburn 1980, pp. 102-03.

- 1 2 Raeburn 1980, p. 103.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, pp. 37, 39.

- 1 2 3 Grodecki 1977, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 Grodecki 1977, p. 41.

- ↑ Mitchell 1968, p. 11.

- 1 2 Raeburn 1980, pp. 103-04.

- ↑ "Hieromartyr Dionysius of Paris, Bishop". oca.org. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, pp. 41, 43.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 28.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 30.

- 1 2 Grodecki 1977, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wim Swaan, The Gothic Cathedral

- 1 2 "Architectural Importance". Durham World Heritage Site. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 37: "Once the relationship of the roofing and the division of interior space, as well as the attendant considerations of articulation and lighting, were fully established and developed, Gothic architecture was born."

- ↑ Oggins, R.O. (2000). "Cathedrals". Metrobooks. Friedman/Fairfax Publishers. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the World's Tallest Buildings". Time Magazine.

- 1 2 3 Grodecki 1977, p. 14.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, pp. 14, 17.

- ↑ Grodecki 1977, p. 17.

- ↑ Ching 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Begun in 1443. "House of Jacques Cœur at Bourges (Begun 1443), aerial sketch". Liam’s Pictures from Old Books. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ↑ -Bob Hunter "Londonderry Cathedtral". BBC.

- ↑ "Gothic Architecture and Churches | Architectural Digest". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

References

- Bony, Jean (1983). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Oakland, United States (California): University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02831-7.

- Ching, Francis D.K. (2012). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-64885-8.

- Der Manuelian, Lucy (2001). "Ani: The Fabled Capital of Armenia". In Cowe, S. Peter. Ani: World Architectural Heritage of a Medieval Armenian Capital. Peeters: Leuven Sterling. ISBN 978-90-429-1038-6.

- Fiske, Kimball (1943). The Creation of the Rococo. Philadelphia, United States (Pennsylvania): Philadelphia Museum of Art.