Lat

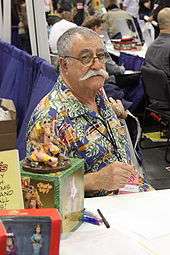

| Datuk Lat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Mohammad Nor Khalid 5 March 1951 Gopeng, Perak, Federation of Malaya (now Malaysia) |

| Occupation | Cartoonist |

| Years active | Since 1974 |

| Notable work |

The Kampung Boy (1979) Scenes of Malaysian Life (1974– ) Keluarga Si Mamat (1968–1994) |

| Relatives | Mamat Khalid (brother) |

| Awards | List of major honours |

| Website | lathouse.com.my |

Datuk Mohammad Nor Khalid (Jawi: محمد نور خالد), more commonly known as Lat, (born 5 March 1951) is a Malaysian cartoonist. Winner of the Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize in 2002, Lat has published more than 20 volumes of cartoons since he was 13 years old. His works mostly illustrate Malaysia's social and political scenes, portraying them in a comedic light without bias. Lat's best known work is The Kampung Boy (1979), which is published in several countries across the world. In 1994, the Sultan of Perak bestowed the honorific title of datuk on Lat, in recognition of the cartoonist's work in helping to promote social harmony and understanding through his cartoons.

Born in a village, Lat spent his youth in the countryside before moving to the city at the age of 11. While in school, he supplemented his family's income by contributing cartoon strips to newspapers and magazines. He was 13 years old when he achieved his first published comic book, Tiga Sekawan (Three Friends Catch a Thief). After failing to attain the grades that were required to continue education beyond high school, Lat became a newspaper reporter. In 1974, he switched careers to be an editorial cartoonist. His works, reflecting his view about Malaysian life and the world, are staple features in national newspapers such as New Straits Times and Berita Minggu. He adapted his life experiences and published them as his autobiographies, The Kampung Boy and Town Boy, telling stories of rural and urban life with comparisons between the two.

Lat's style has been described as reflective of his early influences, The Beano and The Dandy. He has, however, come into his own way of illustration, drawing the common man on the streets with bold strokes in pen and ink. A trademark of his Malay characters is their three-loop noses. Lat paid attention to family life and children because of his idolisation of Raja Hamzah, a senior cartoonist who was also popular in the 1960s with his comics about swashbuckling heroes. Rejabhad, a well-respected cartoonist, was Lat's mentor, and imbued the junior cartoonist with a preference to be sensitive to the subjects of his works. Lat's attention to details gained him popularity, endearing his works to the masses who find them believable and unbiased.

Aside from writing and publishing cartoons, Lat has ventured into the fields of animation, merchandising, and theme parks with his creations. His name and works are recognised internationally; foreign cartoonists, such as Matt Groening and Sergio Aragonés, admire his art, and foreign governments invite Lat to tour their countries, hoping to gain greater exposure for their countries through Lat's cartoons of his experiences in them. After 27 years of living and working in Kuala Lumpur, Lat moved back to Ipoh for a more sedate lifestyle in semi-retirement.

Childhood and education

Mohammad Nor Khalid was born on 5 March 1951 in a kampung (village) in Gopeng, Perak, Malaysia. His father was a government clerk with the Malaysian Armed Forces, and his mother a housewife.[1] Khalid was a stocky boy with a cherubic face, which led his family to nickname him bulat (round). His friends shortened it to "Lat"; it became the name by which he was more commonly known in his kampung and later in the world.[1][2][3] Lat was the eldest child in his family,[nb 1] and he often played in the jungles, plantations, and tin mines with his friends.[1][nb 2] Their toys were usually improvised from everyday sundries and items of nature.[4] Lat liked to doodle with materials provided by his parents,[8] and his other forms of recreation were reading comics and watching television; Lat idolised local cartoonist Raja Hamzah, who was popular with his tales of swashbuckling Malay heroes.[9] Malaysian art critic and historian Redza Piyadasa believes Lat's early years in the kampung ingrained the cartoonist with pride in his kampung roots and a "peculiarly Malay" outlook—"full of [...] gentleness and refinement".[10]

Lat's formal education began at a local Malay kampung(village) school; these institutions often taught in the vernacular and did not aspire to academic attainment.[11] The boy changed schools several times; the nature of his father's job moved the family from one military base to another across the country, until they settled back at his birthplace in 1960.[12][13] A year later, Lat passed the Special Malay Class Examination, qualifying him to attend an English medium boarding school—National Type Primary School—in the state's capital, Ipoh.[1][14] His achievement helped his father make the decision to sell their kampung estate and move the family to the town;[15] society in those days considered education at an English medium school a springboard to a good future.[16][17] Lat continued his education at Anderson School,[18] Perak's "premier non-missionary English medium school".[1][19] Redza highlights Lat's move to Ipoh for higher schooling as a significant point in the cartoonist's development; the multi-racial environment helped establish his diverse friendships, which in turn broadened his cultural perspectives.[20]

At the age of nine, Lat began to supplement his family's income through his artistic skills, by drawing comics and selling them to his friends.[1] Four years later, in 1964, the young cartoonist achieved his first published work: a local movie magazine—Majallah Filem—printed his comic strips, paying him with movie tickets.[21] Lat's first comic book publication, Tiga Sekawan (Three Friends Catch a Thief), was published by Sinaran Brothers that year. The company had accepted Lat's submission, mistaking him for an adult and paying him 25 Malaysian ringgits (RM) for a story about three friends who band together to catch thieves.[22] In 1968, at the age of 17, Lat started penning Keluarga Si Mamat (Mamat's Family), a comic strip for Berita Minggu (the Sunday edition of Berita Harian). The series ran in the paper every week for 26 years.[21] Although still a schoolboy, Lat was earning a monthly income of RM100, a large sum in those days, from his cartoons.[21] His education finished two years later at the end of Form 5; his Third Grade in the Senior Cambridge examinations was not enough for him to advance to Form 6.[23] Graduating with an education equivalent to that of high school, Lat started looking for a job and had his sights set on becoming an illustrator.[6]

Reporter to cartoonist

_(between_Lebuh_Pudu_and_Lebuh_Pasar_Besar%2C_Jalan_Yap_Ah_Loy)%2C_central_Kuala_Lumpur.jpg)

Moving to the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur, Lat applied for a cartoonist's position at Berita Harian. He was told there was no vacancy, but the paper's editor, Abdul Samad Ismail, offered him the post of a crime reporter.[4] Lat accepted, a decision he explained was borne from necessity rather than choice: "It was a question of survival. I had to earn money to help support the family."[1] At that time, Lat's father had fallen seriously ill and could not work; Lat had to become the breadwinner of his family.[24] Aside from taking the job, he continued contributing cartoons to other publications.[4] Lat was later transferred to Berita's parent publication, New Straits Times.[25][nb 3] Moving throughout the city to report on crimes gave Lat opportunities to observe and interact with the myriads of lives in the urban landscape, enabling him to gather material for his cartoons and increasing his understanding of the world.[4] Nevertheless, he felt he lacked the persistently inquisitive nature needed to succeed as a crime reporter.[27] Furthermore, his "breathtakingly detailed, lurid and graphically gory descriptions" of the aftermaths of crimes had to be frequently toned down by his seniors.[28] Lat became convinced that he was a failure at his job, and his despondency led him to tender his resignation. Samad, believing Lat had a bright future with the press, furiously rejected the letter.[29]

Lat's career took a turn for the better on 10 February 1974; Asia Magazine, a periodical based in Hong Kong, published his cartoons about Bersunat—a circumcision ceremony all Malaysian boys of the Islamic faith have to undergo.[1][30][31] The cartoons impressed Tan Sri Lee Siew Yee, editor-in-chief of the New Straits Times.[32] Lee found Lat's portrayal of the important ceremony humorous yet sensitive, and grumbled that the newspaper should have hired the artist. He was surprised to be told that Lat was already working within his organisation.[12] Lat was called to Lee's office to have a talk, which raised the reporter's profile in the company. He became the paper's column cartoonist, taking up a position created for him by Samad, now deputy editor of the New Straits Times.[33][34] His first duty was to document Malaysian culture in a series of cartoons titled Scenes of Malaysian Life.[35] The newspaper also sent him to study for four months at St Martin's School of Art in London,[36] where he was introduced to English editorial cartoons and newspapers. Returning to Malaysia full of fascination with his experience, Lat transformed Scenes of Malaysian Life into a series of editorial cartoons. His approach proved popular, and at the end of 1975 he was appointed full-time cartoonist with total freedom in his work.[37]

Lat produced a steady stream of editorial cartoons that entertained Malaysian society. By 1978, two collections of his works (Lots of Lat and Lat's Lot) had been compiled and sold to the public. Although Malaysians knew of Lat through Scenes of Malaysian Life, it was his next work that propelled him into national consciousness and international recognition.[21][27] In 1979, Berita Publishing Sendirian Berhad published Lat's The Kampung Boy, an autobiographical cartoon account of his youth. The book was a commercial hit; according to Lat, the first printing—60,000 to 70,000 copies—sold out within four months of the book's release.[4] Readers of the book were captivated by his "heart-warming" portrayal of Malaysian rural life,[38] rendered with "scribbly black-and-white sketches" and accompanied by "simple but eloquent prose".[39] By 2009, the book has been reprinted 16 times[nb 4] and published in several other countries in various languages, including Portuguese, French, and Japanese.[22][40] The success of The Kampung Boy established Lat as the "most renowned cartoonist in Malaysia."[21]

After The Kampung Boy

.jpg)

In 1981, Town Boy was published. It continued The Kampung Boy's story, telling of the protagonist's teenage life in an urban setting. Two more compilations of Lat's editorial cartoons (With a Little Bit of Lat and Lots More Lat) were published and the number of people who recognised him continued to grow.[41] In 1984, partly from a desire to step away from the limelight, Lat resigned from the New Straits Times to become a freelancer,[4][42] but continued to draw Scenes of Malaysia Life for the newspaper. He set up his own company, Kampung Boy Sendirian Berhad (Village Boy private limited), to oversee the merchandising of his cartoon characters and publishing of his books.[43][44] In 2009, Kampung Boy partnered Sanrio and Hit Entertainment in a project to open an indoor theme park which would later be called as Puteri Harbour Family Theme Park in Nusajaya, Johor in August 2012.[45] One of the park's attractions will be the sight of performers dressed up as Kampung Boy characters beside those in Hello Kitty and Bob the Builder costumes[46][47] and also reported in August 2012 will be a Lat-inspired diner called Lat's Place.[45] It will be designed in a Malaysian village setting, coupled with animations for patrons to interact with.[45]

Lat has experimented with media other than paper. In 1993 he produced a short animated feature, Mina Smiles, for Unesco; the video, featuring a female lead, was for a literacy campaign.[48] Personal concerns motivated Lat for his next foray into animation; judging that Western animation of the 1980s and 90s had negative influences, he wanted to produce a series for Malaysian children that espoused local values.[49] The result was Kampung Boy the television series (1997), an adaptation of his trademark comic. The 26-episode series received positive reviews for technical details and content.[50] There were comments on its similarities to The Simpsons, and on its English which was not entirely local.[51] His most recent involvement with animation was in 2009; Lat's Window to the World, a musical animated feature, played at the Petronas Philharmonic Hall. Lat had been commissioned to help create three animated vignettes based on The Kampung Boy to accompany the instruments of the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra.[12] The scores, composed by Carl Davis, complemented Lat's visuals, capturing the spirit of kampung childhood in a "simple, idyllic past".[52]

In 1997, after 27 years of living in Kuala Lumpur,[53] Lat moved back to Ipoh with his family. Aside from retreating slightly from the cartooning scene, he wanted to be close to his old kampung and let his children experience life in a small town or village;[6][22] he had married in 1977,[54] and the couple have four children—two daughters and two sons.[55][56] Lat said that raising his children has helped him cope with the pressures of his fame and made him realise that he might be losing touch with the new generation of Malaysians who have different tastes in cartoons.[57] His wife helps him in his work, scanning his completed cartoons and emailing them to the newspaper offices in Kuala Lumpur. Lat still draws with his usual pens and inks, avoiding the use of computers except to read his emails.[58] In 2011–12, he is to join other artists from around the world in Italy for the Civitella Ranieri Fellowship programme. During their one-month stay, they are encouraged to share ideas in an environment fostered to stimulate their creativity.[59]

Art style

Lat covers various genres in his works. His portfolio is diverse; John A. Lent, a scholar of Asian cartoons, found it to difficult to classify the cartoonist into any particular field.[60] In his Keluarga Si Mamat series, Lat drew slapsticks and satires that examined the encounters between traditional and modern values. Humorous stories of children at play also populated the series.[61] Jennifer Rodrigo Willmott, writer for Reader's Digest, stated that:

Lat's cartoon characters have always been ordinary people—a villager in his checkered sarong, a money-changer in his white dhoti, a Malay government servant in his bush jacket and sometimes even Lat himself: that character with the flat, round face; the nose slightly off centre; the untidy mop of dark, curly hair; and the constant toothy grin.[1]

Using a large cast of characters—a wide assortment of personalities and cultures—allows Lat to comment on a wider range of topics than is possible with a small group of characters.[62] Malaysian comics scholar Muliyadi Muhamood commented that the humour in Lat's cartoons is evoked through graphical and textual means; "short, compact dialogues" and puns form the text while "facial expressions and actions" of the characters help to bring out the funny side of things.[63] Muliyadi further stated that Lat's works offer many levels of interpretation; one reader would laugh at Lat's cartoon for its slapstick, while another would find the same work hilarious for its subtle critique of society. As an example, Muliyadi referred to a Keluarga Si Mamat strip published in 1972. Malaysia was facing a shortage of qualified physical education teachers then, and such duties were often placed on the shoulders of teachers of other faculties. Lat illustrated an obese teacher who conducted a physical education session to his eventual collapse. Muliyadi suggested that the cartoon could be interpreted as a simple tease of the teacher's plight, a suggestion to examine the curriculum taught (change physical education to an informal session), a remark on the shortage of teachers, or more extremely, a criticism of the government's failure to prevent the situation from happening.[64]

The narration of Lat's early cartoons, such as Tiga Sekawan and Keluarga Si Mamat, was in Malay.[13] His later works, however, were mostly in English; Scenes of Malaysian Life ran only in the English-language New Straits Times.[65] The English idiom in his works reflects the local pidgin form—"Malglish"—containing smatterings of Malay words and a simpler grammatical structure.[66] After a string of successful English publications, Lat worried he had neglected Malaysians who were not proficient in English. He drew Mat Som, a story of a kampung boy who moved to the city to work as a writer and courted a pretty city girl. The comic was in Malay and a commercial hit; its first print of 30,000 copies sold out in three months. Far Eastern Economic Review journalist Suhaini Aznam remarked that Lat's strength was his ability to portray the plight of the common man in a satiric light without any form of bias.[67]

Early style

Lat's artistic skills were cultivated from youth and self-taught. The cartoonist believes he inherited the talent and interest from his father, who doodled as a hobby and was notorious for his sense of humour as the "village jester".[22][68] Lat says his siblings were also gifted in drawing, but they never bothered to develop their talents.[12] His parents actively encouraged him to develop his artistic skills, although his father occasionally told him not to make a career of it.[69] He also received encouragement from outside his family; Lat's primary school teacher Mrs Moira Hew (the inspiration for one of his characters, the Butterfly-Glassed Lady),[14] helped nurture his gift, frequently asking him to illustrate lessons in class.[13] Her teachings expanded Lat's mind and made him more receptive to ideas that looked beyond his kampung.[70]

The early influences on his art style were from the West. Like most of the Malaysian children in the 1950s, Lat watched Hanna-Barbera cartoons (The Flintstones and The Jetsons) on television and read imported British comics, such as The Dandy and The Beano. He studied them and used their styles and themes in his early doodles.[8][21] After the foreign influences in his works were noticed by a family friend, Lat was advised by his father to observe and draw upon ideas from their surroundings instead. Heeding the advice, the young cartoonist intimated himself with local happenings.[21][71] Tiga Sekawan was conceived as a humorous crime-fighting story of a local flavour.[43] Keluarga Si Mamat and its protagonist were named after his youngest brother Mamat,[6] its stories based on Lat's observations of his fellow villagers and schoolmates.[72] The inspiration for his cartoons about Bersunat came about when he was on assignment at a hospital. As he was taking breaks from investigating the dead victims of crime brought to the morgue, Lat chanced upon the circumcisions performed by the hospital on ethnic Malay boys. He found their experiences clinical, devoid of the elaborate and personal ceremonies that celebrated his own rite to manhood in the village. Lat felt compelled to illustrate the differences between life in his kampung and the city.[73]

When Lat formally entered the cartooning industry, he was not totally unfamiliar with the profession. He had the benefit of the mentorship of Rejabhad, an experienced political cartoonist. Rejabhad was well respected by his countrymen, who titled him the "penghulu (chief) of Malay cartoonists".[1] After noticing Lat's submissions to newspapers and magazines, he corresponded with the young cartoonist.[1] When Rejabhad was requested by Lat's mother to take care of her 15-year-old son in the cartooning industry, he accepted.[43] He gave advice and influenced Lat's growth as a cartoonist. Lat treated Rejabhad with great respect, holding up his mentor as a role model.[74] The affection and admiration was mutual. Thirty-six years after taking Lat under his wing, Rejabhad recounted their relationship in these words:

Lat and I are so far apart but so close in heart. When I meet him, my mouth is sewed up. When the love is very close, the mouth is dumb, can't speak a word. Lat is on top of the mountain, as he doesn't forget the grass at the foot of the mountain. When he goes here and there, he tells people I'm his teacher.[43]

Rejabhad was not the first local figure to have exerted an influence on Lat. Raja Hamzah, popular with his action comics and ghost stories, was Lat's "hero" in his childhood.[75] It was Raja Hamzah's cartoons of local swashbuckling adventurers that inspired Lat to become a cartoonist.[9] Tiga Sekawan was the culmination of that desire, the success after numerous failed submissions and an affirmation to Lat that he could become a cartoonist like his idol.[76] Raja Hamzah also had success with comic strips on family life, such as Mat Jambul's Family and Dol Keropok and Wak Tempeh. These cartoons imbued Lat with a fascination of family life and the antics of children, which served him well in his later works.[77] Lat was interested in studying the details of his surroundings and capturing them in his works. Keluarga Si Mamat and The Kampung Boy faithfully depicted their characters' appearances and attitudes. Their narrations were written in a style that was natural to the locals. Thus, Lat was able to make his readers believe his stories and characters were substantially "Malay".[78]

Later style

After his study trip to London in 1975, Lat's works exhibited the influences of editorial cartoonists such as Frank Dickens, Ralph Steadman, and Gerald Scarfe.[79] In 1997, Ron Provencher, a professor emeritus at Northern Illinois University, reported that Lat's style reminded his informants on the Malaysian cartooning scene of The Beano.[80] Muliyadi elaborated that The Beano and The Dandy's "theme of a child's world" is evident in Lat's Keluarga Si Mamat.[81] Others commented that Lat's art stood out on its own. Singaporean cartoonist Morgan Chua believed that Lat "managed to create an impressively local style while remaining original",[31] and although comics historian Isao Shimizu found Lat's lines "somewhat crude", he noted that the cartoonist's work was "highly original" and "full of life".[82] Redza's judgement was that The Beano and The Dandy were "early formative [influences]" on Lat before he came into his own style.[83] Lent gave his assessment in 1999:

It is Lat's drawing that is so evocative, so true to life, despite its very exaggerated distortion. Lat's Malaysian characters are distinguished by their ethnic linkages (for example, his Malay characters have three loop noses), which in itself, is no mean feat. The drawings are bold strokes, expressive dialogue in English and Bahasa Malaysian, as well as in what portends to be Chinese, Tamil, and entertaining backgrounds that tell their own stories.[4]

Lat's work with pen and ink so impressed Larry Gonick that the American cartoonist was tempted into experimenting with this medium for part of his The Cartoon History of the Universe. Gonick tried to use the medium as he did his regular brushes; however, the results proved unsatisfactory.[84] Lat occasionally colours his works, such as those in his Kampong Boy: Yesterday and Today (1993), using watercolour or marker pens.[58] According to Lent, Redza judged that Lat had "elevated cartooning to the level of 'high visual arts' through his social commentary and 'construction of the landscape'".[43] The art critic was not alone in having a high regard for Lat's works. Jaafar Taib, cartoonist and editor of Malaysian satirical magazine Gila-Gila, found Lat's cartoons retained their humour and relevance throughout time. He explained that this quality arose from the well-thought-out composition of Lat's works, which helped to clearly express the ideas behind the cartoons.[43]

| He is at one and the same time childlike and mature, outrageous and delicate, Malaysian and universal. He always gets away with a lot mainly because his humour is utterly free from malice, sharp but never wounding, coaxing us irresistibly to laugh with him at the delectable little absurdities around us and within us. Typical Malaysian foibles most of these, yet as foreign fans testify, they touch chords in people from other cultures too.

His drawings and comments have an air of spontaneity, as if they had been scrawled just a minute or so before press time. In fact they are products of painstaking research as well as naturally acute observation, of patient professionalism as well as inspiration. This is evident in pieces like the Sikh Wedding, to the devastating accuracy of which a Sikh has smilingly sworn.– Adibah Amin, respected Malaysian writer, introduction of Lots of Lat (1977)[85] |

Sensitive topics

At the time that Lat started drawing for the New Straits Times, local political cartoonists were gentle in their treatment of Malaysian politicians; the politicians' features were recreated faithfully and criticisms were voiced in the form of subtle poems. Lat, however, pushed the boundaries; although he portrayed the politicians with dignity, he exaggerated notable features of their appearances and traits.[86] Lat recalled that in 1974, he was told to change one of his works, which portrayed Malaysian Prime Minister Abdul Razak from the back.[87] Lee refused to print the work unchanged, and pointedly asked the cartoonist "You want to go to jail?!"[88] In 1975, however, Lat's next attempt at a political cartoon won Lee's approval.[89] The satire featured a caricature of Razak's successor—Hussein Onn—on the back of a camel, travelling back to Kuala Lumpur from Saudi Arabia; its punchline was Hussein's hailing of his mount to slow down after reading news that a pay raise for the civil service would be enacted on his return.[37]

Malaysia's political class grew comfortable with Lat's caricatures, and like the rest of the country, found them entertaining.[90] Muliyadi described Lat's style as "subtle, indirect, and symbolic", following traditional forms of Malaysian humour in terms of ethics and aesthetics. The cartoonist's compliance with tradition in his art earned him the country's respect.[91] When Lat was critical of politicians, he portrayed them in situations "unusual, abnormal or unexpected" to their status or personalities, using the contrast to make the piece humorous.[92] Mahathir bin Mohamad, Malaysia's fourth Prime Minister, was Lat's frequent target for much of his political career, providing more than 20 years worth of material to the cartoonist—enough for a 146-page compilation Dr Who?! (2004).[93] Lat's political wit targeted not only local politicians, but also Israeli actions in the Middle East and foreign figures such as prominent Singaporean politician Lee Kwan Yew.[94] Despite his many works of political nature, Lat does not consider himself a political cartoonist[95] and openly admits that there are others better than he is in this field.[96]

Lat prefers to portray his ideas with as little antagonism as possible. He heeds the advice of his mentor, Rejabhad, and is aware of sensitivities, especially those of race, culture, and religion.[1] As he devises the concept for his cartoon, he eliminates anything he believes to be malicious or insensitive.[97] At the Fourth Asian Cartoon Exhibition in Tokyo, Lat revealed that when it came to making religious comments in his work, he only did so on his own religion (Islam).[98] In such cases, Lat uses his art to help educate the young about his faith.[99] Lat trusts his editors to do their jobs and cull what is socially unacceptable for print. In an interview, he revealed his discomfort with the concept of self-publishing, believing that unadulterated or unsupervised cartoon drawing could lead to "rubbish". He prefers to be assertive in areas with which he is comfortable or competent.[100] Lat is adamant on not changing what he has already drawn; several pieces of his cartoons remain unpublished because editors refused to print them unchanged.[101] When that happens, the editors spike (blank) the space for his regular cartoon in the newspaper. Lat admitted of his unprinted works: "Okay, maybe I've pushed the line a little bit, but I've never got into trouble and, frankly, only a handful of my cartoons were ever spiked."[31]

Interests and beliefs

Music has played a crucial part in Lat's life since his youth; he revealed in an interview that listening to songs such as Peggy March's "I Will Follow Him" and Paul & Paula's "Hey Paula" helped him learn English.[13] Listening to music had also become an important ritual in his work, providing him with inspiration in his art. When he sketches "fashionable girls", he puts on Paul McCartney's tracks, and switches to Indonesian gamelan when he needs to draw intricate details.[1] He enjoys pop music, particularly rock music of the 1950s and 60s,[31] listening to The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Elvis Presley.[12] Lat is also partial to country music, and to singers such as Hank Williams and Roy Rogers because he finds their tunes "humble".[102] His enjoyment of music is more than a passive interest; he is proficient with the guitar and piano, and can play them by ear.[1]

Malaysian society used to look down on cartoonists, assuming that those who practised the trade were intellectually inferior to writers, or were lesser artists;[103][104] Lat was not the only cartoonist to be paid with movie tickets in the 1950s; Rejabhad once received one ticket for ten cartoons, and many others were likewise recompensed,[105][106] or were paid very little money.[83] Despite the lowly reputation of his profession at that time, Lat is very proud of his choice of career; he once took umbrage with an acquaintance's girlfriend for her presumption that the words and ideas in his cartoons were not his own.[103] Drawing cartoons is more than a career to him:

If it is a job then how come it's been going on for 33 years, from childhood to now? A job is something you do at a certain time. You go to work, you finish it, you retire. If this is a job, then by now I should have retired. But I am still drawing. It's not a job to me. It is something expected of me.— Lat (2007)[22]

The elongated "L" in Lat's signature was born from his joy in completing a work.[102] He professes that his primary aim in drawing cartoons is to make people laugh; his role as a cartoonist is "to translate the reaction of the people into humorous cartoons".[6] He has no intentions to preach his beliefs through his art, believing that people should be free to make up their own minds and that the best he can do is to make readers ponder the deeper meanings behind a humorous scene.[107] The reward he has sought from drawing since his youth is simple:

It gives a good feeling when people are amused by your funny drawings, especially for a kid. I felt like an entertainer when my drawings were shown to relatives and friends, and they laughed or even smiled.[6]

Lat's pride in cartooning pushed him to promote the art as a respectable career. In 1991, he banded together with fellow cartoonists Zunar, Rejabhad, and Muliyadi to start "Pekartun" (Persatuan Kartunis Selangor dan Kuala Lumpur). This association holds exhibitions and forums, to raise public awareness of cartooning and to build relationships among its members. It also helps to clarify legal issues such as copyrights to its members, and acts as an intermediary between them and the government.[108][109] In the previous year, Lat's company, Kampung Boy, had organised the first Malaysian International Cartoonists Gathering, bringing together cartoonists from several countries across the world to exhibit their art and participate in conferences to educate others in their work.[110] In Redza's opinion, Lat played a great role in making cartooning respectable among his fellow Malaysians.[104]

Aside from promoting the rights of fellow cartoonists, Lat developed an interest in encouraging conservation of the natural environment. Several of his works caricature the consequences of pollution and over-exploitation of resources.[111] Invited to give a speech at the 9th Osaka International Symposium on Civilisation in 1988, Lat talked about the environmental problems associated with overpopulation and heavy industrialisation. He further reminisced about the simple cleaner life he had enjoyed as a child in the kampung.[112] In 1977, when a protest was organised against logging activities in the Endau-Rompin Reserves, Lat helped gain support for the movement by drawing cartoons in the newspapers that highlighted the issue.[113] Lat is also particularly concerned over what he sees as the negative side of urban development. He believes that such developments have contributed to the loss of the traditional way of life; people forget the old culture and values as they ingratiate themselves with the rapid pace and sophistication of urban lifestyles. His defence and fondness of the old ways are manifested in his The Kampung Boy, Town Boy, Mat Som, and Kampung Boy: Yesterday and Today, which champion the old lifestyles as spiritually superior.[114]

Influence and legacy

Recognised globally, and widely popular in his country, Lat has been styled "cultural hero",[115] "his nation's conscience in cartoon form"[116] and "Malaysian icon"[117] among other effusive titles.[49][118] The Malaysian Press Institute felt Lat had "become an institution in [his] own right", honouring him with their Special Jury Award in 2005.[119] Cartoonists in the Southeast Asian region, such as Muliyadi, Chua, and Rejabhad, have given high praise to Lat,[31][43] and his admirers further abroad include North American cartoonists Matt Groening and Eddie Campbell.[3][120] Groening, creator of The Simpsons, gave a testimonial for the United States version of The Kampung Boy, praising Lat's signature work as "one of the all-time great cartoon books".[121] Sergio Aragonés, the creator of Groo the Wanderer, is another of Lat's American fans. After visiting Malaysia in 1987, Aragonés used the experience to create a story for Groo in which the bumbling swordsman chances on the isle of Felicidad, whose inhabitants and natural habitat were modelled after those of the Southeast Asian country. Aragonés drew the noses of the islanders in Lat's distinctive style, and named one of the prominent native characters—an inquisitive boy—after the Malaysian cartoonist.[122][nb 5]

Lent (2003) and Shimizu (1996) both suggest that the Malaysian comic industry began to boom after Lat joined the profession on a full-time basis in 1974.[123][124] Lent further hazards that the cartoonist profession was made more respectable in Malaysia by the award to Lat in 1994 of a datuk title (equivalent to a knighthood).[108][125] Bestowed on Lat by the Sultan of Perak, the title was Malaysia's highest recognition of the cartoonist's influence on his countrymen and his contributions to the country.[55] Before Lat's emergence, Malaysian cartooning was largely unappreciated by the public, despite the popular works of Raja Hamzad and Rejabhad.[126] Lat's successes showed Malaysians that they could thrive and succeed as cartoonists, and inspired them to look to the cartooning profession for potential careers.[108] Several younger artists imitated his style in the hopes of capturing equivalent rewards.[43] Zambriabu and Rasyid Asmawi copied the distinctive three loop noses and hairstyles of Lat's characters. Others, such as Reggie Lee and Nan, incorporated Lat's detailed "thematic and stylistic approaches" in their works.[127] Muliyadi dubbed Lat the "Father of Contemporary Malaysian Cartoons", for being the first Malaysian cartoonist to achieve global recognition and for helping to improve the industry's image in their country.[128]

The effects of Lat's works were not confined to the artistic sector. In the period before his debut, Malaysian cartoonists supported calls for national unity. The characters in a cartoon were often of one race, and negative focus on the foibles of particular races or cultures worked its way into the mainstream.[129][130] Such cartoons did not help to soothe racial tensions that were simmering then. The situation erupted with the racial riots of 1969, and for several years after these incidents relationships among the races were raw and fragile.[131][132] According to Redza, Lat soothed the nation's racial woes with his works.[132] Drawing members of various races in his crowd scenes and showing their interactions with one another, Lat portrayed Malaysians in a gentle and unbiased comic manner.[31] Redza pointed out although one may argue that Lat was forced into the role of racial and cultural mediator (because of his employment with his country's "leading English-language newspaper serving a multi-racial readership"), he possessed the necessary qualities—intimate knowledge of various races and culture—to succeed in the job.[133] Lat's fans recognised the trademark of his oeuvre as "a safe and nice humour that made everyone feel good and nostalgic by appealing to their benevolent sides rather than by poking at their bad sides".[134] It proved to be a successful formula; more than 850,000 copies of his books were sold in the twelve years after the first compilation of his editorial cartoons went on sale in 1977.[1] The comfort that readers sought from his works was such that when in September 2008 Lat deviated from his usual style, to draw a cartoon about racially charged politicking in his country, it shocked journalist Kalimullah Hassan. She found the illustration of a group of Malaysians huddled under an umbrella, taking shelter from a rain of xenophobic phrases, full of profound sadness.[135]

Lat's works have been used in academic studies—the fields of which are diverse, spanning law,[136] urban planning,[137] and diets.[138] The academics use his drawings to help them illustrate their points in a humorous yet educational manner.[112] Foreign embassy officials have sought Lat for his insight into the cultures of their societies. They have invited him to tour their countries, in the hope that he will record his experiences in cartoon form to share with the world.[1][95] The first country to do so was the United States, followed by others such as Australia, Germany, and Japan.[95][139] In 1998, Lat became the first cartoonist to be made an Eisenhower Fellow and revisited the United States;[55] his research programme was the study of relationships among the many races in United States society.[4][140] In 2007, the National University of Malaysia awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in Anthropology and Sociology.[141] Lat's works are recognised as visual records of Malaysia's cultural history;[142] he was awarded a Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize in 2002 for preserving Malay rural culture in his works.[55]

In 1986, Lat became the first cartoonist to exhibit his work at the National Museum in Kuala Lumpur; the event drew a record number of 600,000 visitors in two months.[1] He is treated as a celebrity,[12][143] and his cartoon characters decorate stamps,[144] financial guides,[145] and aeroplanes.[146] When Reader's Digest asked Malaysians in 2010 to rank which of 50 local personalities was most worthy of trust, Lat was returned fourth on the list.[147] According to Jaafar, "100% of Malaysians respect and admire Lat, and see a Malaysian truth, whether he is drawing a policeman, teachers, or hookers."[148]

List of major honours

- 1994 – Honorific title of datuk

- 1998 – Eisenhower Fellowship

- 2002 – Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize

- 2005 – Petronas Journalism Awards (Special Jury Award)

- 2007 – Honorary Doctorate in Anthropology and Sociology

- 2010 – Civitella Ranieri Visual Arts Fellowship

List of selected works

This is a partial list of Lat's books (first prints); excluded are translations and commissioned works, such as Latitudes (1986) for Malaysian Airlines[1] and the annual personal financial management guides (since 1999) for Bank Negara Malaysia.[145]

- Tiga Sekawan: Menangkap Penchuri [Three Friends Catch a Thief] (in Malay). Penang, Malaysia: Sinaran Brothers. 1964.

- Lots of Lat. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. February 1977.

- Lat's Lot. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. June 1978.

- The Kampung Boy. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1979.

- Keluarga Si Mamat [Mamat's Family] (in Malay). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1979.

- With a Little Bit of Lat. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1980.

- Town Boy. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1981.

- Lots More Lat. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1980.

- Lat and His Lot Again!. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1983. ISBN 967-969-404-6.

- Entahlah Mak...! [I Don't Know, mother...!] (in Malay). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1985. ISBN 967-969-076-8.

- It's a Lat Lat Lat Lat World. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1985. ISBN 967-969-075-X.

- Lat and Gang. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1987. ISBN 967-969-157-8.

- Lat with a Punch. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1988. ISBN 967-969-180-2.

- Better Lat than Never. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1989. ISBN 978-967-969-211-2.

- Mat Som (in Malay). Selangor, Malaysia: Kampung Boy. 1989. ISBN 967-969-075-X.

- Lat as Usual. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1990. ISBN 967-969-262-0.

- Be Serious Lat. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1992. ISBN 967-969-398-8.

- Kampung Boy: Yesterday and Today. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1993. ISBN 967-969-307-4.

- Lat 30 Years Later. Selangor, Malaysia: Kampung Boy. 1994. ISBN 983-99617-4-8.

- Lat Was Here. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1995. ISBN 967-969-347-3.

- Lat Gets Lost. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1996. ISBN 967-969-455-0.

- The Portable Lat. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1998. ISBN 967-969-500-X.

- Lat at Large. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 1999. ISBN 967-969-508-5.

- Dr Who?!: Capturing the Life and Times of a Leader in Cartoons. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 2004. ISBN 967-969-528-X.

- Lat: The Early Series. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Publishing. 2009. ISBN 978-983-871-037-4.

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Lat has a sister and two brothers. Willmott noted that before Lat left his kampung, he had only a younger sister and brother.[1] His youngest brother, film maker Mamat Khalid, was born when Lat was 12 years old, about the time he moved to the city.[4][5][6]

- ↑ Perak's sources of tin were mostly placer deposits, which were mined mainly with huge bucket dredges.[7]

- ↑ In 1972, the investment arm of UMNO, a political body invested as the Malaysian government, bought out the Malaysian operations of Straits Times Press, including Berita Harian. The bought over publications were placed under the management of the New Straits Times Press, which is also the name of its main publication.[1][26]

- ↑ Specifics of reprint: The Kampung Boy (Sixteenth reprint ed.). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing. 2009 [1979]. ISBN 978-967-969-410-9.

- ↑ The issue concerned is Groo the Wanderer No. 55, "The Island of Felicidad", New York, United States: Marvel-Epic Comics, September 1989.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Willmott 1989.

- ↑ Campbell 2007a.

- 1 2 Cha 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lent 1999.

- ↑ Azhariah 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 More than a Cartoonist 2007, p. 258.

- ↑ Salma & Abdur-Razzaq 2005, pp. 95–98.

- 1 2 Lent 2003, p. 258.

- 1 2 Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 9:45–9:59.

- ↑ Redza 2003, pp. 85–87.

- ↑ Ungku 1956, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gopinath 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin 2006.

- 1 2 The Lat Story 2000.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 51.

- ↑ Rudner 1994, p. 334.

- ↑ Thompson 2007, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Sager 2003.

- ↑ Anderson School 2005.

- ↑ Redza 2003, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rohani 2005, p. 390.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chua 2007.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 53.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 20:27–20:45.

- ↑ Pameran Retrospektif Lat 2003, p. 100.

- ↑ Edge 2004, p. 185.

- 1 2 Bissme 2009.

- ↑ Redza 2003, p. 90.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 21:54–22:39.

- ↑ Pameran Retrospektif Lat 2003, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jayasankaran 1999, p. 36.

- ↑ History of New Straits Times 2007.

- ↑ Nor-Afidah 2002.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 27:05–27:23.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 213.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 30:35–31:15.

- 1 2 Muliyadi 2004, p. 214.

- ↑ Chan 1999.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2006.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, pp. 537–538.

- ↑ Chin 1998, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 38:45–39:35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lent 2003, p. 261.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 Lee, Liz (1 August 2012). "Khazanah invests RM115mil in theme park in Nusajaya". thestar.com.my. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ Satiman & Chuah 2009.

- ↑ Zazali 2009.

- ↑ Pameran Retrospektif Lat 2003, p. 101.

- 1 2 Muliyadi 2001, p. 146.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2001, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Rohani 2005, p. 391.

- ↑ Yoong 2009.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 43:41–43:49.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Rohani 2005, p. 400.

- ↑ Pameran Retrospektif Lat 2003, p. 103.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 39:35–40:07.

- 1 2 Campbell 2007c.

- ↑ Civitella Ranieri Foundation 2010.

- ↑ Lent 2004, p. xiv.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 163–170.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 270.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, p. 74.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 163–164, 270–275.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 216.

- ↑ Lockard 1998, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Suhaini 1989, p. 42.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 3:34–4:29.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 50.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 14:15–15:00.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 52.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 16:51–17:01.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 22:53–24:00.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 208.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 133.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 10:40–11:08, 11:57–12:01.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 133–162.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 161–162, 170–171.

- ↑ Ooi 2003.

- ↑ Lent 2003, p. 285.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, p. 57.

- ↑ Shimizu 1996, p. 29.

- 1 2 Redza 2003, p. 85.

- ↑ Surridge 2000, p. 66.

- ↑ Redza 2003, pp. 92, 94.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Lent 2003, p. 266.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 32:35–32:55.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 33:45–35:13.

- ↑ Zaini 2009, p. 205.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, p. 68.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, p. 72.

- ↑ Tribute to 'Dr Who?' 2004.

- ↑ Lent 2003, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 Campbell 2007b.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 57.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 56.

- ↑ International Dateline 1999.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Telling Stories Through Cartoons 2009.

- ↑ Lent 2003, p. 270.

- 1 2 Krich 2004, p. 50.

- 1 2 Chin 1998, p. 48.

- 1 2 Redza 2003, p. 98.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 131.

- ↑ Lent 1994, p. 118.

- ↑ Chin 1998, pp. 55–56.

- 1 2 3 Lent 2003, p. 271.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003b, p. 294.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003b, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Zaini 2009, pp. 205–206.

- 1 2 Zaini 2009, p. 207.

- ↑ Kathirithamby-Wells 2005, p. 321.

- ↑ Redza 2003, pp. 96, 98.

- ↑ Rohani 2005, p. 389.

- ↑ Krich 2004, p. 48.

- ↑ Jayasankaran 1999, p. 35.

- ↑ More than a Cartoonist 2007, p. 257.

- ↑ Pakiam 2005.

- ↑ Azura & Foo 2006.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, p. 539.

- ↑ Barlow 1997.

- ↑ Lent 2003, p. 260.

- ↑ Shimizu 1996, p. 30.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 42:31–42:43.

- ↑ Redza 2003, p. 84.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, pp. 63–66.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003a, p. 79.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 96.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2003b, p. 297.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 110–115.

- 1 2 Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 28:41–29:35.

- ↑ Redza 2003, p. 93.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ Kalimullah 2008.

- ↑ Foong 1994, p. 100.

- ↑ Bunnell 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ Candlish 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ Smith 2001, p. 349.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ Goh 2007.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 57–58.

- ↑ Top 10 Influential Celebrities 2009.

- ↑ Kampung Boy Graces 2008.

- 1 2 Bank Negara Malaysia 2005.

- ↑ Pillay 2004.

- ↑ Malaysians Trust Nicol 2010.

- ↑ Krich 2004, p. 49.

Bibliography

Interviews/self-introspectives

- Eddie, Campbell; Lat (subject) (11 January 2007). "Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 1". First Hand Books—Doodles and Dailies. New York, United States: First Second Books. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Eddie, Campbell; Lat (subject) (12 January 2007). "Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 2". First Hand Books—Doodles and Dailies. New York, United States: First Second Books. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Eddie, Campbell; Lat (subject) (15 January 2007). "Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 3". First Hand Books—Doodles and Dailies. New York, United States: First Second Books. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Telling Stories Through Cartoons". AsiaOne. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings. New Straits Times. 2 May 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- "The Lat Story". The Lat Home. Selangor, Malaysia: Kampung Boy. 2000. Archived from the original on 10 December 2000. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- Books

- Bunnell, Tim (2004). "Kuala Lumpur City Centre (KLCC): Global Reorientation". Malaysia, Modernity and the Multimedia Super Corridor: A Critical Geography of Intelligent Landscapes. RoutledgeCurzon Pacific Rim Geographies. 4. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 65–89. ISBN 0-415-25634-8. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- Candlish, John (1990). "Backdrop: The Ghost at Every Banquet". Dietary Imbalances, Metabolism, and Disease: The Southeast Asian Perspective. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 9971-69-145-0. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- Chin, Phoebe, ed. (March 1998). "The Kampung Boy". S-Files, Stories Behind Their Success: 20 True Life Malaysian Stories to Inspire, Challenge, and Guide You to Greater Success. Selangor, Malaysia: Success Resources Slipguard. ISBN 983-99324-0-3.

- Foong, James (1994). The Malaysian Judiciary: a Record from 1786 to 1993. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malayan Law Journal. ISBN 0-409-99693-9.

- Kathirithamby-Wells, Jeyamalar (2005). "Development and Environmentalism". Nature and Nation: Forests and Development in Peninsular Malaysia. Hawaii, United States: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 307–336. ISBN 0-8248-2863-1. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Lockard, Craig (1998). "Popular Music and Political Change in the 1980s". Dance of Life: Popular Music and Politics in Southeast Asia. Hawaii, United States: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 238–247. ISBN 0-8248-1918-7. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Muliyadi Mahamood (2003a). "Lat Dalam Konteksnya" [Lat in Context]. Pameran Retrospektif Lat [Retrospective Exhibition 1964–2003]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Art Gallery. pp. 48–82. ISBN 983-9572-71-7.

- Muliyadi Mahamood (2004). The History of Malay Editorial Cartoons (1930s–1993). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Utusan Publications and Distributions. ISBN 967-61-1523-1.

- Pameran Retrospektif Lat [Retrospective Exhibition 1964–2003]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Art Gallery. 2003. ISBN 983-9572-71-7.

- Redza Piyadasa (2003). "Lat the Cartoonist—An Appreciation". Pameran Retrospektif Lat [Retrospective Exhibition 1964–2003]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Art Gallery. pp. 84–99. ISBN 983-9572-71-7.

- Rudner, Martin (1994). "Education, Development and Change in Malaysia". Malaysian Development: A Retrospective. Ontario, Canada: Carleton University Press. pp. 299–348. ISBN 0-88629-221-2. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- Salma Nasution Khoo; Abdur-Razzaq Lubis (2005). Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development. Perak, Malaysia: Perak Academy. ISBN 983-42113-0-9. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- Thompson, Eric (2007). "Circulation and Migration". Unsettling Absences: Urbanism in Rural Malaysia. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press. pp. 68–88. ISBN 9971-69-336-4. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- Zaini Ujang (2009). "Books Strengthen the Mind". The Elevation of Higher Learning. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malaysian National Institute of Translation. pp. 201–208. ISBN 983-068-464-4. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Academic sources

- Edge, Marc (2004). "Pie Sharing or Food Fight? The Impact of Regulatory Changes on Media Market Competition in Singapore". In Schmid, Bert; et al. The Impact of Regulatory Change on Media Market Competition and Media Management: A Special Double Issue of the International Journal on Media Management. International Journal on Media Management. 6. St. Gallen, Switzerland: University of St. Gallen. pp. 184–193. ISBN 0-8058-9500-0. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- Goldsmith, Francisca (15 September 2006). "Kampung Boy". Booklist. Vol. 103 no. 2. Illinois, United States: American Library Association. p. 61. ISSN 0006-7385. Proquest ID: 1134269391. Retrieved 17 April 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Haslina Haroon (2008). "The Adaptation of Lat's The Kampung Boy for the American Market". Membina Kepustakaan Dalam Bahasa Melayu [Build a Library in the Malay Language]. International Conference on Translation. 11. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malaysian National Institute of Translation. pp. 537–549. ISBN 983-192-438-X. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Lent, John (May–August 1994). "Political Adversaries and Agents of Social Change: Editorial Cartoonists in Southeast Asia". Asian Thought and Society. New York, United States: East-West Publishing. 19 (56): 107–123. ISSN 0361-3968.

- Lent, John (April 1999). "The Varied Drawing Lots of Lat, Malayasian Cartoonist". The Comics Journal. Washington, United States: Fantagraphics Books (211): 35–39. ISSN 0194-7869. Archived from the original on 15 February 2005. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Lent, John (Spring 2003). "Cartooning in Malaysia and Singapore: The Same, but Different". International Journal of Comic Art. 5 (1): 256–289. ISSN 1531-6793.

- Lent, John (2004). "Preface". Comic Art in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Latin America Through 2000: An International Bibliography. Bibliographies and Indexes in Popular Culture. 11. Connecticut, United States: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. xi–xvii. ISBN 0-313-31210-9. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Muliyadi Mahamood (2001). "The History of Malaysian Animated Cartoons". In Lent, John. Animation in Asia and the Pacific. Indiana, United States: Indiana University Press. pp. 131–152. ISBN 0-253-34035-7.

- Muliyadi Mahamood (Spring 2003b). "An Overview of Malaysian Contemporary Cartoons". International Journal of Comic Art. 5 (1): 292–304. ISSN 1531-6793.

- Rohani Hashim (2005). "Lat's Kampong Boy: Rural Malays in Tradition and Transition". In Palmer, Edwina. Asian Futures, Asian Traditions. Kent, United Kingdom: Global Oriental. pp. 389–400. ISBN 1-901903-16-8.

- Smith, Wendy (2001) [1994]. "Japanese Cultural Images in Malaysia". In Jomo Kwame Sundaram. Japan and Malaysian Development: In the Shadow of the Rising Sun. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 335–363. ISBN 0-415-11583-3. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Surridge, Matthew (June 2000). "Larry Gonick". The Comics Journal. Washington, United States: Fantagraphics Books (224): 34–68. ISSN 0194-7869.

Journalistic sources

- "Anderson School, Ipoh, Perak". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. 5 June 2005. p. 72. Proquest ID: 849526371. Retrieved 14 March 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Azhariah Kamin (22 July 2005). "A Local Movie About Rock Culture". The Star Online. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Azura Abas; Foo, Heidi (16 December 2006). "Lat's "Kampung Boy" Makes It Big in US". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 10. ProQuest ID: 1181979521. Retrieved 14 March 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Barlow, Henry Sackville (September 1997). "Editorial". Malaysian Naturalist. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malayan Nature Society. 51 (1): 1. ISSN 1511-970X.

- Bissme, S (30 April 2009). "Kampung Boy Unveiled". Sun2Surf. Selangor, Malaysia: Sun Media. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Cha, Kai-Ming (20 November 2007). "Lat's Malaysian Memories". PW Comics Week. New York, United States: Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Chan, Daniel (15 June 1999). "'Kampung Boy' wins award". The Malay Mail. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 15. Proquest ID: 42386559. Retrieved 24 July 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Chua, Siew Ching (September 2007). "Seriously, Lat". The Hilt. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Hilton Hotels (10). ISSN 1823-9382. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Crossings: Datuk Lat (Television production). Singapore: Discovery Networks Asia. 21 September 2003.

- Goh, Lisa (11 August 2007). "It's Dr Lat now – 'Kampung Boy' Awarded Doctorate". The Star. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Gopinath, Anandhi (8 June 2009). "Cover: Our Kampung Boy". The Edge. Selangor, Malaysia: The Edge Communications Sdn Bhd (758). Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "International Dateline—Taking Cartoons Seriously". Look Japan. Tokyo, Japan: Look Japan. 45 (524): 4. November 1999. ISSN 0456-5339.

- Jayasankaran, S (22 July 1999). "Going Global". Far Eastern Economic Review. Hong Kong: Dow Jones & Company. 162 (29): 35–36. ISSN 0014-7591. Proquest ID: 43402018. Retrieved 12 March 2010. (Registration required (help)).

- Kalimullah Hassan (21 September 2008). "The Colours of Malaysia". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 20. Proquest ID: 1558723771. Retrieved 4 July 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Kampung Boy Graces Our Stamps". The Star. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. 27 November 2008. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Krich, John (15 April 2004). "Lats of Laughs". Far Eastern Economic Review. Hong Kong: Dow Jones & Company. 167 (15): 48–50. ISSN 0014-7591. Proquest ID: 617798341. Retrieved 12 March 2010. (Registration required (help)).

- Pillay, Suzanna (26 May 2004). "Airborne with the Kampung Boy". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 5. Proquest ID: 642258141. Retrieved 4 July 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Lat Comes Out with Tribute to 'Dr Who?'". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. 21 December 2004. p. 14. Proquest ID: 768868741. Retrieved 16 June 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Malaysians Trust Nicol the Most". AsiaOne. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings. The Star/Asia News Network. 28 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- Martin, Sumitha (4 June 2006). "I Abhorred Mathematics". New Straits Times Sunday Edition. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 15. ProQuest ID: 1048291141. Retrieved 14 March 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- "More than a Cartoonist". Annual Business Economic and Political Review: Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Oxford Business Group. 2 (Emerging Malaysia 2007): 257–258. January 2007. ISSN 1755-232X. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- Ooi, Kok Chuen (27 December 2003). "Lat – Then, Now and Forever". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 5. Proquest ID: 516000751. Retrieved 4 July 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Pakiam, Ranjeetha (30 November 2005). "Lat Honoured with Award". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. Proquest ID:. (Subscription required (help)).

- Sager Ahmad (27 September 2003). "Anderson Old Boys Gear Up to Help Alma Mater". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 4. Proquest ID: 413669291. Retrieved 14 March 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Satiman Jamin; Chuah, Bee Kim (12 November 2009). "First Indoor Theme Park Set in Nusajaya". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Shimizu, Isao (December 1996). "Culture Feature—Understanding the Population Problem Through Cartoons". Look Japan. Tokyo, Japan: Look Japan. 42 (489): 28–30. ISSN 0456-5339.

- Suhaini Aznam (14 December 1989). "Quipping Away at Racism". Far Eastern Economic Review. Hong Kong: Dow Jones & Company. 146 (50): 42–43. ISSN 0014-7591. Proquest ID: 435880. Retrieved 12 March 2010. (Registration required (help)).

- "Top 10 Influential Celebrities in Malaysia: Stars with the X-factor Sizzle". AsiaOne. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings. New Straits Times. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Ungku Abdul Aziz (1956). Lim, Tay Boh, ed. "The Causes of Poverty in Malayan Agriculture". Problems of the Malayan Economy: A Series of Radio Talks. Background to Malaya. Singapore: Donald Moore (10): 11–15.

- Willmott, Jennifer Rodrigo (March 1989). "Malaysia's Favourite Son". Reader's Digest. Vol. 134 no. 803. New York, United States: The Reader's Digest Association. ISSN 0034-0375. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- Yoong, Christy (10 May 2009). "Music Heightened the Action and Emotions in the Works of an Actor and a Cartoonist". The Star Online. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- Zazali Musa (10 November 2009). "Johor Not Competing with Singapore for Theme Park Visitors". The Star Online. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

Online sites

- "Bank Negara Malaysia Releases "Buku Wang Saku" and "Buku Perancangan dan Penyata Kewangan Keluarga" for 2006" (Press release). Bank Negara Malaysia. 29 December 2005. Archived from the original on 27 May 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- "News". Civitella Ranieri Center. Civitella Ranieri Foundation. 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- "History of New Straits Times". NSTP. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: The New Straits Times Press. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman (10 October 2002). "Samad Ismail". Infopedia. Singapore: National Library Board. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

External links

![]() Media related to Lat at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lat at Wikimedia Commons