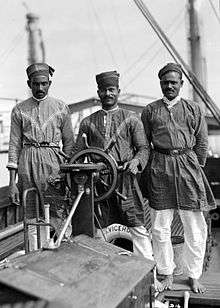

Lascar

A lascar was a sailor or militiaman from South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Arab world, and other territories located to the east of the Cape of Good Hope, who were employed on European ships from the 16th century until the middle of the 20th century.

The Hindi word lashkar (army) derives from al-askar, the Arabic word for a guard or soldier. The Portuguese adapted this term to "lascarim", meaning Asian militiamen or seamen, specifically from any area east of the Cape of Good Hope. This means that Indian, Malay, Chinese and Japanese crewmen were covered by the Portuguese definition. The British of the East India Company initially described Indian lascars as 'Black Portuguese' or 'Topazes', but later adopted the Portuguese name, calling them 'lascar'.[1] Lascars served on British ships under "lascar agreements." These agreements allowed shipowners more control than was the case in ordinary articles of agreement. The sailors could be transferred from one ship to another and retained in service for up to three years at one time. The name lascar was also used to refer to Indian servants, typically engaged by British military officers.[2]

History

Sixteenth century

Indian seamen had been employed on European ships since the first European made the sea voyage to India. Vasco da Gama, the first European to reach India by sea (in 1498), hired an Indian pilot at Malindi (a coastal settlement in what is now Kenya) to steer the Portuguese ship across the Indian Ocean to the Malabar Coast in southwestern India. Portuguese ships continued to employ lascars from South Asia in large numbers throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, mainly from Goa and other Portuguese colonies in India. The Portuguese applied the term "lascar" to all sailors on their ships who were originally from the Indies, which they defined as the areas east of the Cape of Good Hope.

Through the Portuguese and Spanish maritime world empires, some South Asian lascars found their way on to British ships, and were among the sailors on the first British East India Company ships to sail to India. Lascar crewmen from South Asia are depicted on Japanese Namban screens of the sixteenth century.[3] The Luso-Asians appear to have evolved their own pidgin Portuguese which was used throughout South and Southeast Asia.[4]

Seventeenth century

When the British adopted the term "lascar", they initially used it for all Asian crewmen, but after 1661 and the ceding of Bombay to England by Portugal, the term was used mainly to describe crewmen from East India. Among other terms was "topaze" to describe Indo-Portuguese naval militia, especially from Bombay, Thana, and former Portuguese territories such as Diu, Damman, Cochin and the Hugli River. The term "sepoy" was used to describe South Asian military militia.

The number of Indian seamen employed on UK ships was so great that the British tried to restrict this by the Navigation Acts in force from 1660, which required that 75 percent of the crew of a British-registered ship importing goods from Asia had to be British. Initially, the need arose because of the high sickness and death rates of European sailors on India-bound ships, and their frequent desertions in India, which left ships short of crew for the return voyage. Another reason was war when conscription of British sailors by the Royal Navy was particularly heavy from Company ships in India.[5]

Eighteenth century

In 1756, a fleet under admirals Pocock and Watson, with an expeditionary force under Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Clive set off from Bombay with 1300 men, including 700 Europeans, 300 sepoys and 300 'topaze Indo-Portuguese'. The expedition against Angria is one of the first references to the British use of Indo-Portuguese militia and one of the first actions of the Bombay Marine. Lascars served with The Duke of Wellington on campaign in India during the late 18th and early 19th century in India.[6]In 1786, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor was originally set up thanks to concern over lascars left in London. However, in a report made after one month of the Committee's existence, it was found that only 35 of the 250 recipients of aid were lascars. On Captain James Cook's ill-fated second voyage to the Pacific, the HMS Resolution, had lost so many men (including Cook) that she had to take on new crew in Asia to get back to England.

Lascars were paid 5% of their fellow white sailors' wages and were often expected to work longer hours as well as being given food of often inferior quality and in smaller portions.[7] The remuneration for lascar crews "was much lower than European or Negro seamen"[8] and "the cost of victualling a lascar crew was 50 percent less than that of a British crew, being six pence per head per day as opposed to twelve pence a day."[8] The lascars lived under conditions not unlike slavery, as shipowners could keep their services for up to three years at a time, moving them from one ship to the next on a whim. The ill-treatment of lascars continued into the 19th century.[7]

Nineteenth century

The British East India Company recruited seamen from areas around its factories in Bengal, Assam and Gujarat, as well as from Yemen, British Somaliland and Portuguese Goa. They were known by the British as lascars.[9] These seamen included South Asian sailors, who would go on to serve on British (and European ships) until the 1960s.

Between 1803 and 1813, there were more than 10,000 lascars from the Indian subcontinent visiting British port cities and towns.[10]:140, 154–6, 160–8, 172 By 1842, 3,000 lascars visited the UK annually, and by 1855, 12,000 lascars were arriving annually in British ports. In 1873, 3,271 lascars arrived in Britain.[11]:35 Throughout the early 19th century lascars visited Britain at a rate of 1,000 every year,[10]:140,54–6,60–8,72 which increased to a rate of 10,000 to 12,000 every year throughout the late 19th century.[12][13] Lascars would normally lodge in British ports in between voyages. [14] Some settled in port towns and cities in Britain, often because of restrictions such as the Navigation Act or due to being stranded as well as suffering ill treatment. Many were abandoned and fell into poverty due to quotas on how many lascars could serve on a single ship. Lascars sometimes lived in Christian charity homes, boarding houses and barracks.[15][16] Some converted to Christianity (at least nominally) as it was legally required to be Christian in order to marry in Britain at this time,[17] the most famous case being the conversion and then marriage of Sake Dean Mahomed to Jane Daly.[18] Marriage of lascars to British women was perhaps partly due to a lack of Asian women in Britain at the time.[10]:111–119, 129–30, 140, 154–6, 160–8, 181[19] At the beginning of World War I, there were 51,616 South Asian lascars working on British ships, the majority of whom were of Bengali descent.[20] Among them, it is estimated 8,000 Indians (some of whom would have been lascars) lived in Britain permanently prior to the 1950s.[13][21]

Language barriers between officers and lascars made the use of translators very important. Very few worked on deck because of the language barrier. Some Europeans managed to become proficient in the languages of their crew. Skilled captains such as John Adolphus Pope became adept linguists and were able to give complicated orders to their lascar crew. Often native bosses known as "serangs", as well as "tindals" who often assisted serangs, were the only men able to communicate directly with the captain and were the men who often spoke for the lascars.[22] [23] Many lascars made attempts to learn English but few would have been able to talk at length to their European captains.[24]

Lascars served on ships for assisted passage to Australia, and on troopships during Britain's colonial wars including the Boer Wars and the Boxer Rebellion. In 1891 there were 24,037 lascars employed on British merchant ships. For example, the ship "Massilia" sailing from London to Sydney, Australia in 1891 lists more than half of its crew as Indian lascars.

By 1815, the Committee Report on Lascars and other Asiatic Seamen introduced new requirements for reimbursing lascar workers, namely that lascar workers be provided with "a bed, a pillow, two jackets and trousers, shoes and two woollen caps.""[8]

Twentieth century

Lascars served all over the world in the period leading up to the First World War. Lascars were barred from landing at some ports, such as in British Columbia. At the beginning of World War I, there were 51,616 lascars working on British merchant ships in and around the British Empire.[25]

In 1932, the Indian National Congress survey of "all Indians outside India" (which included modern Pakistani and Bangladeshi territories) estimated that there were 7,128 Indians living in the United Kingdom, which included students, lascars, and professionals such as doctors [26]

In World War II thousands of lascars served in the war and died on vessels throughout the world, especially those of the British India Steam Navigation Company, P&O and other British shipping companies.

The lack of Canadian naval manpower led to the employment of a total of 121 Catholic Goans and 530 Muslim British Indians on the Empress vessels of the Canadian Pacific Railway, such as the Empress of Asia and Empress of Japan. These ships served in the Indian Ocean both as ANZAC convoy ships and in actions at Aden. The ships were placed under the British Admiralty as part of Canada's contribution to the war effort and all of the South Asian men were awarded medals by the Admiralty, though none of them were delivered.[27]

Lascars in the Mascarene Islands

Presumably because Muslim lascars manned the "coolie ships" that carried Indian and Chinese indentured labour to the sugar plantations of the Mascarene Islands, the term lascar is also used in Mauritius, Réunion and the Seychelles to refer to Muslims, by both Muslims and non-Muslims.

Lascars in Britain

Lascars began living in England in small numbers from the mid-17th century as servants as well as sailors on English ships. Baptism records show that a number of young men from the Malabar coast were brought to England as servants.[28] Lascars arrived in larger numbers in the 18th and 19th centuries, when the British East India Company began recruiting thousands of lascars (mostly Bengali Muslims, but also Konkani-speaking Christians from the northern part of Portuguese Goa and Muslims from Ratnagiri District in the adjacent Maharashtra) to work on British ships and occasionally in ports around the world. Despite prejudice and a language barrier, some lascars settled in British port cities, often forcibly due to ill-treatment on British ships as well as being unable to leave due to restrictions such as the Navigation Act and abandonment by shipping masters.[28][29][30] Shipowners would face penalties for leaving lascars behind.[31] This measure was intended to discourage settlement of Asian sailors in Britain.[31]

Lascars often lived in Christian charity homes, boarding houses and barracks and sometimes cohabited with local British women. The first and most frequent South Asian travelers to Britain were Christian Indians and those of European-Asian mixed race. For Muslim Indians considerations about how their dietary and religious practices would alienate them from British society were brought into question but these considerations were often outweighed by economic opportunities. Those that stayed often took British names, dress and diet.[10]:12

Although the South Asian presence in London during the 19th century mainly constituted male lascars and sailors, some women were included. British soldiers would occasionally marry Indian women while overseas and send their mixed-race children back to Britain, although the wife often did not accompany them. Indian wives of British soldiers would sometimes ask for passage home after being abandoned or widowed if they did accompany their children. In 1835, Bridget Peter, a native of the Madras region of India, lost her husband, a British soldier serving in His Majesty's 1st Foot Regiment. She petitioned the directors from Chelsea Hospital "in a state of destitution". They paid to return her and her three children to India.[10]:186

The issue of British women cohabiting with lascars became an issue, and a magistrate of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets area in 1817 expressed "disgust" at how the local English women in the area were marrying and cohabiting with foreign Indian lascar seamen. Nevertheless, there were no legal restrictions against "mixed" marriages in Britain.[10]:106, 111–116, 119–20, 129–35, 140–2, 154–8, 160–8, 172, 181[11]:58[32] Indian lascar sailors established some of England's first settled Asian-British inter-racial families in the dock areas of major port cities.[33] This led to a small number of "mixed race" children being born in the country. Ethnic minority women in Britain were often outnumbered by "half-caste Indian" daughters born from white mothers and Indian fathers.[34] The most famous of these mixed-race children was Albert Mahomet, born with a lascar father and English mother. He went on to write a book about his life called From Street Arab to Pastor.

Lascars commonly suffered from poverty in Britain. In 1782, East India Company records describe lascars coming to their Leadenhall Street offices ‘reduced to great distress and applying to us for relief’.[35] In 1785 a letter writer in The Public Advertiser wrote of "miserable objects, lascars, that I see shivering and starving in the streets." During the 1780s it was not uncommon to see lascars starving on the streets of London. The East India Company responded to criticism of the lascars' treatment by making available lodgings for them, but no checks were kept on the boarding houses and barracks they provided. The lascars were made to live in cramped, dreadful conditions which resulted in the deaths of many each year, with reports of lascars being locked in cupboards and whipped for misbehaviour by landlords. Their poor treatment was reported on by the Society for the Protection of Asiatic Sailors (which was founded in 1814).[30][36]

A letter in The Times stated that "The lascars have been landed from the ship ... One of them has since died...the coffin being filled with food and money, under the idea that the food would maintain him till his arrival in the new other world... Some of the poor fellows have hitherto been shivering about the streets, wet and half-naked, exhibiting a picture of misery but little creditable to the English nation".[37]

In 1842, the Church Missionary Society reported on the dire ″state of the lascars in London″.[38] In 1850 40 lascars, also known as ″Sons of India,″ were reported to have starved to death in the streets of London.[39] Shortly after these reports, evangelical Christians proposed the construction of a charity house and gathered £15,000 in assistance of the lascars. In 1856 "The Strangers' Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders" was opened in Commercial Road, Limehouse under the manager, Lieutenant-Colonel R. Marsh Hughes. The home helped and supported lascars and sailors from as far as China. The home helped with employment and with leaving Britain. Additionally, it served as a repatriation centre where various sailors were recruited for ships returning East. It was also used as a missionary centre with Joseph Salter of the London City Mission as its missionary. Among the things provided by the home were a library of Christian books in Asian and African languages, a store room for valuables, and a place where Lascars could send their earnings back to India.[40] Lascars were allowed entrance as long as they had the prospect of local employment, or were on a ship returning East.[28] The collective naming of these groups as "strangers" reflects British attitudes at the time.[38]

Lascar immigrants were often the first Asians to be seen in British cities and were initially perceived as indolent due to their reliance on Christian charities.[41]

In 1925 the Coloured Alien Seamen Order 1925 Act was brought into law by the Secretary of State for the Home Department. It stated that "any coloured alien seaman who is not already registered should take steps to obtain a Certificate of Registration without delay." Any foreign seaman, regardless of whether they had been in Britain for several months, had to register with the police. In 1931, 383 Indians and Ceylonese were registered.[42]

A letter dated 7 September 1925, from the wife of a Peshawar-born Indian domiciled in Britain and working as a sailor, describes the treatment of some South Asians who were British subjects under the Home Office Coloured Aliens Seamen's Order, 1925: My husband landed at Cardiff, after a voyage at sea on the SS Derville as a fireman, and produced his Mercantile Marine Book, R.S 2 No. 436431, which bears his Certificate of Nationality, declaring him to be British, and is signed by a Mercantile Marine Superintendent, dated 18 August 1919. This book and its certificate were ignored, and my husband was registered as an Alien. Would you kindly inform me if it is correct that the Mercantile Marine Book should have been ignored as documentary proof?"[43]Police eager to deport ''coloured'' seamen would often (and illegally) register seamen as aliens regardless of correct documentation.[44]

The transitory presence of lascars continued into the 1930s, with the Port of London Authority mentioning lascars in a February 1931 article, writing that: "Although appearing so out of place in the East End, they are well able to look after themselves, being regular seamen who came to the Docks time after time and have learnt a little English and know how to buy what they want."[45]

In 1932, the Indian National Congress survey of 'all Indians outside India' estimated that there were 7,128 Indians in the United Kingdom, which included students, lascars, and professionals such as doctors. The resident Indian population of Birmingham was recorded at 100. By 1945 it was 1,000. [26]

During the 1940s many thousands of lascars served in World War II and died on vessels throughout the world.

In the 1950s the use of the term lascar declined with the ending of the British Empire. The Indian “Lascar Act” of 1832 was finally repealed in 1963[46] However, "traditional" Indian deck and Pakistani engine crews continued to be used in Australia until 1986 when the last crew was discharged from the P&O and replaced by a general-purpose crew of Pakistanis.[47]

Lascars in Canada

Lascars were on board late 18th-century and early 19th-century ships arriving on the Pacific coast of north-west North America. In most cases the ships sailed from Macau, though some came from India. When the Gustavus III arrived at Clayoquot Sound on the coast of Vancouver Island, the ship's crew included three Chinese, one Goan and one Filipino.[48] Lascars were barred from entry to British Columbia and other Canadian ports from June 1914 until the late 1940s. Therefore, they seldom occur on landing and embarkation records, though they were frequenting the ports but remaining on board the ships.[49]

Lascars in Macau and Hong Kong

After the death of James Cook in Hawaii, the HMS Resolution sailed to Macau with her cargo of furs from the north-west coast of North America. The ship was very undermanned and took on fresh crew at Macau in December 1779 including a lascar from Calcutta by the name of Ibraham Mohammed.[50]

Lascars were arriving in Hong Kong before the 1842 Treaty of Nanking. Since the island of Hong Kong was initially a naval base there were South Asian lascars of the East Indies Fleet arriving at Hong Kong in those early colonial days. Lascars were housed at several streets in the Sheung Wan area where there are two roads called Upper Lascar Row and Lower Lascar Row.[51] These are not far from the barracks established in 1847 at Sai Ying Pun for Indian soldiers or sepoys.[52]

Lascars in the US

Lascars were on board early British voyages to the north-west coast of North America. These sailors were among the multinational crew arriving from Asia in seek of furs. Among these was the Nootka in 1786 that arrived at the Russian port of Unalaska and sailed on to Prince William Sound in Alaska. There were ten South Asian and one Chinese Lascar on this vessel. Three Lascars died in Prince William Sound, Alaska. The Nootka sailed back to Asia via Hawaii, and the lascars became the first recorded South Asians to sail to Alaska and Hawaii.[53]

Lascar ranks and positions

In both deck and engine room departments, the lascars were headed by a serang (equivalent to the boatswain in the deck department), assisted by one or more tindals (equivalent to boatswain's mates in the deck department). Other senior deck positions included seacunny (quartermaster), mistree (carpenter, although a European carpenter was often carried), and kussab or cassab (lamp trimmer). An apprentice in either department was known as a topas or topaz. The senior lascar steward was known as the butler (either answering to a European chief steward or in charge of the catering department himself in a small ship). A cook was known as a bhandary.

Portrayal in literature and cinema

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created a Lascar foil to Sherlock Holmes in "The Man with the Twisted Lip". Lascars aboard the ship Patna figure prominently in the early chapters of Joseph Conrad's novel Lord Jim. Frances Hodgson Burnett's novel A Little Princess features a lascar named Ram Dass. Also, Caleb Carr portrays two lascars as bodyguards for a Spanish diplomat near the end of The Angel of Darkness. In Wuthering Heights, it is speculated that Heathcliff, the main character, may be of lascar origin.[54][55] Amitav Ghosh's book Sea of Poppies portrays the British East India Company and their use of lascar crews. Shahida Rahman's Lascar (book) (2012) is the story of an East Indian lascar's journey to Victorian England. In the H. P. Lovecraft short story The Call of Cthulhu, Gustaf Johansen, the last living seaman of an expedition to Cthulhu's sunken city R'lyeh, is assassinated (probably with poison needles) by two "lascar sailors" belonging to the evil Cult of Cthulhu. In D. W. Griffith's 1919 silent film Broken Blossoms, the opium house in London that the protagonist goes to is described on the intertitle as "Chinese, Malays, lascars, where the Orient squats at the portals of the West."

See also

- Lascar Row

- Lascar War Memorial

- Lascars in Fiji

- Lascarins

- Sake Dean Mahomed

- Visa policy of the United Kingdom

References

- ↑ "Bengali-speaking community in the Port of London - Port communities - Port Cities". www.portcities.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ Butalia, Romesh C (1999), The evolution of the Artillery in India, Allied Publishers, p. 239, ISBN 81-7023-872-2

- ↑ Lisboa, Luiz Carlos; Arakaki, Mara Rúbia (1993). Namban: o dia em que o Ocidente descobriu o Japão. São Paulo: Aliança Cultural Brasil-Japão.

- ↑ Jayasuriya, Shihan de Silva (2008). The Portuguese in the East: A Cultural History of a Maritime Trading Empire. London: Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 191ff. ISBN 978-0-85771-582-1.

- ↑ Fisher, Michael H.; Lahiri, Shompa; Thandi, Shinder S. (2007). A South-Asian History of Britain: Four Centuries of Peoples from the Indian Sub-continent. Westport, CT: Greenwood World Pub. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978-1-84645-008-2.

- ↑ Arthur Wellesley Duke of Wellington; John Gurwood (omp.) (1837). The Dispatches of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington, K.G.: India, 1794-1805. London: J. Murray. p. 279.

- 1 2 "The Lascars of London and Liverpool". Exodus.

- 1 2 3 Myers, Norma (1994-07-01). "The black poor of London: Initiatives of Eastern Seamen in the eighteenth and ninteenth centuries". Immigrants & Minorities. 13 (2-3): 7–21. ISSN 0261-9288. doi:10.1080/02619288.1994.9974839.

- ↑ Halliday, Fred (2010). Britain's First Muslims: Portrait of an Arab Community. I.B. Tauris. p. 51. ISBN 1848852991. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fisher, Michael H. (2004). Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain, 1600-1857. Delhi: Permanent Black. ISBN 978-81-7824-154-8.

- 1 2 Ansari, Humayun (2004). The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-685-1..

- ↑ Robinson-Dunn, Diane (February 2003). "Lascar Sailors and English Converts: The Imperial Port and Islam in late 19th-Century England". Seascapes, Littoral Cultures, and Trans-Oceanic Exchanges. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- 1 2 Behal, Rana P.; van der Linden, Marcel (eds.). "Coolies, Capital and Colonialism: Studies in Indian Labour History". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 114.

- ↑ "The lascars' lot". The Hindu newspaper.

- ↑ Halliday, Fred (2010). Britain's First Muslims: Portrait of an Arab Community. I.B. Tauris. p. 51. ISBN 1848852991. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ "Law and Imperialism: Criminality and Constitution in Colonial India and Victorian Britain".

- ↑ "Counterflows to Colonialism".

- ↑ Fisher, Michael H. (2006-01-01). Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain, 1600-1857. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 9788178241548.

- ↑ Halliday, Fred (2010). Britain's First Muslims: Portrait of an Arab Community. I.B. Tauris. p. 51. ISBN 1848852991. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Ansari, Humayun (2004). The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 1-85065-685-1.

- ↑ visram (2002). Asians In Britain. pp. 254–269.

- ↑ "P&O Indian and Pakistani Crews". www.pandosnco.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ↑ Frykman, Niklas (2013-12-19). Mutiny and Maritime Radicalism in the Age of Revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107689329.

- ↑ Jaffer, Aaron (2015-11-17). Lascars and Indian Ocean Seafaring, 1780-1860: Shipboard Life, Unrest and Mutiny. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781783270385.

- ↑ "The Infidel Within: Muslims in Britain Since 1800".

- 1 2 Visram, Rozina (2015-07-30). Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700-1947. Routledge. ISBN 9781317415336.

- ↑ Research by Clifford J Pereira, Vancouver, 2016, British Columbia. Canada.

- 1 2 3 "The Goan community of London - Port communities - Port Cities". www.portcities.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ "Bengalis in London's East End" (PDF). Bengalis in London.

- 1 2 Nijhar, Preeti (2015-09-30). Law and Imperialism: Criminality and Constitution in Colonial India and Victorian England. Routledge. ISBN 9781317316008.

- 1 2 "Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700-1947".

- ↑ Fisher, Michael Herbert (2006). "Working across the Seas: Indian Maritime Labourers in India, Britain, and in Between, 1600–1857". International Review of Social History. 51: 21–45. doi:10.1017/S0020859006002604.

- ↑ "Growing Up". Moving Here. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ↑ Rose, Sonya O.; Frader, Laura Levine (1996). Gender and Class in Modern Europepublisher=Cornell University Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-8014-8146-5.

- ↑ "Law and Imperialism: Criminality and Constitution in Colonial India and ...".

- ↑ "LMA Learning Zone > schooLMAte > Black and Asian Londoners > Timeline". www.learningzone.cityoflondon.gov.uk. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Law and Imperialism: Criminality and Constitution in Colonial India and Victorian Britain".

- 1 2 Fisher, Michael H. (2006). "Working across the seas: Indian maritime labourers in India, Britain, and in between, 1600-1857". In Behal, Rana P.; van der Linden, Marcel (eds.). Coolies, Capital and Colonialism: Studies in Indian Labour History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-69974-7.

- ↑ "Law and Imperialism: Criminality and Constitution in Colonial India and Victorian England".

- ↑ "Strangers' Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders". The Open University.

- ↑ Fathom archive. ""British Attitudes towards the Immigrant Community". Columbia University".

- ↑ "Ethnic Labour and British Imperial Trade: A History of Ethnic Seafarers in the UK".

- ↑ Bond, XiaoWei. "Asians in Britain: Ayahs, Servants and Sailors". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ↑ "Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain".

- ↑ "Lascars In The Port of London - Feb. 1931". www.lascars.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ "P&O Indian and Pakistani Crews". www.pandosnco.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ↑ "P&O Indian and Pakistani Crews". www.pandosnco.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ↑ Snow, Captain Elliot, ed. (1925). Adventures at Sea in the Great Age of Sail: Five Firsthand Narratives. New York: Dover. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-486-25177-6.

- ↑ Research by Clifford J. Pereira, 2015, Vancouver BC, Canada.

- ↑ Marshall, James Stirrat; Marshall, Carrie (1960). Pacific voyages: selections from Scots magazine, 1771-1808. Portland,OR: Binfords & Mort. p. 21.

- ↑ Research by Pereira, Clifford J. 2016. Hong Kong, SAR. China.

- ↑ Chi Man, Kwong & Yiu Lun, Tsoi. "Eastern Fortress - A Military History of Hong Kong, 1840-1970". Hong Kong, SAR, China 2014, p.10

- ↑ Portlock, W. H.; Cook, James; Anderson, G. W.; Bligh, William; de Warville, P. Brissot (1794). A new, complete and universal collection of authentic and entertaining voyages and travels to all the various parts of the world... London: Alex. Hogg. p. 122.

- ↑ Michie, E (Winter 1992). "From Simianized Irish to Oriental Despots: Heathcliff, Rochester and Racial Difference". NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction. 25 (2): 125. doi:10.2307/1346001.

- ↑ Tytler, Graeme (1994). "Physiognomy in Wuthering Heights". Brontë Society Transactions. 21 (4): 137–148. doi:10.1179/030977694796439250.(subscription required)

External links

| Look up lascar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |