Laparoscopic surgery

| Laparoscopic surgery | |

|---|---|

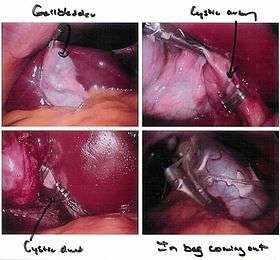

Cholecystectomy as seen through a laparoscope |

Laparoscopic surgery, also called minimally invasive surgery (MIS), bandaid surgery, or keyhole surgery, is a modern surgical technique in which operations are performed far from their location through small incisions (usually 0.5–1.5 cm) elsewhere in the body.

There are a number of advantages to the patient with laparoscopic surgery versus the more common, open procedure. Pain and hemorrhaging are reduced due to smaller incisions and recovery times are shorter. The key element in laparoscopic surgery is the use of a laparoscope, a long fiber optic cable system which allows viewing of the affected area by snaking the cable from a more distant, but more easily accessible location.

There are two types of laparoscope: (1) a telescopic rod lens system, that is usually connected to a video camera (single chip or three chip), or (2) a digital laparoscope where the charge-coupled device is placed at the end of the laparoscope.[1]

Also attached is a fiber optic cable system connected to a "cold" light source (halogen or xenon), to illuminate the operative field, which is inserted through a 5 mm or 10 mm cannula or trocar. The abdomen is usually insufflated with carbon dioxide gas. This elevates the abdominal wall above the internal organs to create a working and viewing space. CO2 is used because it is common to the human body and can be absorbed by tissue and removed by the respiratory system. It is also non-flammable, which is important because electrosurgical devices are commonly used in laparoscopic procedures.[2]

Laparoscopic surgery includes operations within the abdominal or pelvic cavities, whereas keyhole surgery performed on the thoracic or chest cavity is called thoracoscopic surgery. Specific surgical instruments used in a laparoscopic surgery include: forceps, scissors, probes, dissectors, hooks, retractors and more.[3] Laparoscopic and thoracoscopic surgery belong to the broader field of endoscopy.

Procedures

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most common laparoscopic procedure performed. In this procedure, 5–10 mm diameter instruments (graspers, scissors, clip applier) can be introduced by the surgeon into the abdomen through trocars (hollow tubes with a seal to keep the CO

2 from leaking). Over one million cholecystectomies are performed in the U.S. annually, with over 96% of those being performed laparoscopically.

There are two different formats for laparoscopic surgery. Multiple incisions are required for technology such as the da Vinci Surgical System, which uses a console located away from the patient, with the surgeon controlling a camera, vacuum pump, saline cleansing solution, cutting tools, etc. each located within its own incision site, but oriented toward the surgical objective.

In contrast, requiring only a single small incision, the "Bonati system" (invented by Dr. Alfred Bonati), uses a single 5-function control, so that a saline solution and the vacuum pump operate together when the laser cutter is activated. A camera and light provide feedback to the surgeon, who sees the enlarged surgical elements on a TV monitor. The Bonati system was designed for spinal surgery and has been promoted only for that purpose.[4][5]

Rather than a minimum 20 cm incision as in traditional (open) cholecystectomy, four incisions of 0.5–1.0 cm, or more recently a single incision of 1.5–2.0 cm,[6] will be sufficient to perform a laparoscopic removal of a gallbladder. Since the gallbladder is similar to a small balloon that stores and releases bile, it can usually be removed from the abdomen by suctioning out the bile and then removing the deflated gallbladder through the 1 cm incision at the patient's navel. The length of postoperative stay in the hospital is minimal, and same-day discharges are possible in cases of early morning procedures.

In certain advanced laparoscopic procedures, where the size of the specimen being removed would be too large to pull out through a trocar site (as would be done with a gallbladder), an incision larger than 10 mm must be made. The most common of these procedures are removal of all or part of the colon (colectomy), or removal of the kidney (nephrectomy). Some surgeons perform these procedures completely laparoscopically, making the larger incision toward the end of the procedure for specimen removal, or, in the case of a colectomy, to also prepare the remaining healthy bowel to be reconnected (create an anastomosis). Many other surgeons feel that since they will have to make a larger incision for specimen removal anyway, they might as well use this incision to have their hand in the operative field during the procedure to aid as a retractor, dissector, and to be able to feel differing tissue densities (palpate), as they would in open surgery. This technique is called hand-assist laparoscopy. Since they will still be working with scopes and other laparoscopic instruments, CO2 will have to be maintained in the patient's abdomen, so a device known as a hand access port (a sleeve with a seal that allows passage of the hand) must be used. Surgeons who choose this hand-assist technique feel it reduces operative time significantly versus the straight laparoscopic approach. It also gives them more options in dealing with unexpected adverse events (e.g. uncontrolled bleeding) that may otherwise require creating a much larger incision and converting to a fully open surgical procedure.

Conceptually, the laparoscopic approach is intended to minimise post-operative pain and speed up recovery times, while maintaining an enhanced visual field for surgeons. Due to improved patient outcomes, in the last two decades, laparoscopic surgery has been adopted by various surgical sub-specialties including gastrointestinal surgery (including bariatric procedures for morbid obesity), gynecologic surgery and urology. Based on numerous prospective randomized controlled trials, the approach has proven to be beneficial in reducing post-operative morbidities such as wound infections and incisional hernias (especially in morbidly obese patients), and is now deemed safe when applied to surgery for cancers such as cancer of colon.

The restricted vision, the difficulty in handling of the instruments (new hand-eye coordination skills are needed), the lack of tactile perception and the limited working area are factors which add to the technical complexity of this surgical approach. For these reasons, minimally invasive surgery has emerged as a highly competitive new sub-specialty within various fields of surgery. Surgical residents who wish to focus on this area of surgery gain additional laparoscopic surgery training during one or two years of fellowship after completing their basic surgical residency. In OB-GYN residency programs, the average laparoscopy-to-laparotomy quotient (LPQ) is 0.55.[7]

The first transatlantic surgery (Lindbergh operation) ever performed was a laparoscopic gallbladder removal.

Laparoscopic techniques have also been developed in the field of veterinary medicine. Due to the relative high cost of the equipment required, however, it has not become commonplace in most traditional practices today but rather limited to specialty-type practices. Many of the same surgeries performed in humans can be applied to animal cases – everything from an egg-bound tortoise to a German Shepherd can benefit from MIS. A paper published in JAVMA (Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association) in 2005 showed that dogs spayed laparoscopically experienced significantly less pain (65%) than those that were spayed with traditional "open" methods. Arthroscopy, thoracoscopy, cystoscopy are all performed in veterinary medicine today. The University of Georgia School of Veterinary Medicine and Colorado State University's School of Veterinary Medicine are two of the main centers where veterinary laparoscopy got started and have excellent training programs for veterinarians interested in getting started in MIS.

Advantages

There are a number of advantages to the patient with laparoscopic surgery versus an open procedure. These include:[8]

- Reduced hemorrhaging, which reduces the chance of needing a blood transfusion.

- Smaller incision, which reduces pain and shortens recovery time, as well as resulting in less post-operative scarring.

- Less pain, leading to less pain medication needed.

- Although procedure times are usually slightly longer, hospital stay is less, and often with a same day discharge which leads to a faster return to everyday living.

- Reduced exposure of internal organs to possible external contaminants thereby reduced risk of acquiring infections.

- There are more indications for laparoscopic surgery in gastrointestinal emergencies as the field develops.[9]

Although laparoscopy in adult age group is widely accepted, its advantages in pediatric age group is questioned. Benefits of laparoscopy appears to recede with younger age. Efficacy of laparoscopy is inferior to open surgery in certain conditions such as pyloromyotomy for Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Although laparoscopic appendectomy has lesser wound problems than open surgery, the former is associated with more intra-abdominal abscesses.[10]

Disadvantages

While laparoscopic surgery is clearly advantageous in terms of patient outcomes, the procedure is more difficult from the surgeon's perspective when compared to traditional, open surgery:

- The surgeon has limited range of motion at the surgical site resulting in a loss of dexterity.

- Poor depth perception.

- Surgeons must use tools to interact with tissue rather than manipulate it directly with their hands. This results in an inability to accurately judge how much force is being applied to tissue as well as a risk of damaging tissue by applying more force than necessary. This limitation also reduces tactile sensation, making it more difficult for the surgeon to feel tissue (sometimes an important diagnostic tool, such as when palpating for tumors) and making delicate operations such as tying sutures more difficult.[11]

- The tool endpoints move in the opposite direction to the surgeon's hands due to the pivot point, making laparoscopic surgery a non-intuitive motor skill that is difficult to learn. This is called the Fulcrum effect[12]

- Some surgeries (carpal tunnel for instance) generally turn out better for the patient when the area can be opened up, allowing the surgeon to see "the whole picture" surrounding physiology, to better address the issue at hand. In this regard, keyhole surgery can be a disadvantage.[13]

Risks

Some of the risks are briefly described below:

- The most significant risks are from trocar injuries during insertion into the abdominal cavity, as the trocar is typically inserted blindly. Injuries include abdominal wall hematoma, umbilical hernias, umbilical wound infection, and penetration of blood vessels or small or large bowel.[14]

The risk of such injuries is increased in patients who have a low body mass index[15] or have a history of prior abdominal surgery. While these injuries are rare, significant complications can occur, and they are primarily related to the umbilical insertion site. Vascular injuries can result in hemorrhage that may be life-threatening. Injuries to the bowel can cause a delayed peritonitis. It is very important that these injuries be recognized as early as possible.[16]

- Some patients have sustained electrical burns unseen by surgeons who are working with electrodes that leak current into surrounding tissue. The resulting injuries can result in perforated organs and can also lead to peritonitis. This risk is eliminated by utilizing active electrode monitoring.[17]

- There may be an increased risk of hypothermia and peritoneal trauma due to increased exposure to cold, dry gases during insufflation. The use of Surgical Humidification therapy, which is the use of heated and humidified CO2 for insufflation, has been shown to reduce this risk.[18]

- Many patients with existing pulmonary disorders may not tolerate pneumoperitoneum (gas in the abdominal cavity), resulting in a need for conversion to open surgery after the initial attempt at laparoscopic approach.

- Not all of the CO

2 introduced into the abdominal cavity is removed through the incisions during surgery. Gas tends to rise, and when a pocket of CO2 rises in the abdomen, it pushes against the diaphragm (the muscle that separates the abdominal from the thoracic cavities and facilitates breathing), and can exert pressure on the phrenic nerve. This produces a sensation of pain that may extend to the patient's shoulders. For an appendectomy, the right shoulder can be particularly painful. In some cases this can also cause considerable pain when breathing. In all cases, however, the pain is transient, as the body tissues will absorb the CO2 and eliminate it through respiration.[19] - Coagulation disorders and dense adhesions (scar tissue) from previous abdominal surgery may pose added risk for laparoscopic surgery and are considered relative contra-indications for this approach.

- Intra-abdominal adhesion formation is a risk associated with both laparoscopic and open surgery and remains a significant, unresolved problem.[20] Adhesions are fibrous deposits that connect tissue to organ post surgery. Generally, they occur in 50-100% of all abdominal surgeries,[20] with the risk of developing adhesions being the same for both procedures.[21][22] Complications of adhesions include chronic pelvic pain, bowel obstruction, and female infertility. In particular, small bowel obstruction poses the most significant problem.[21] The use of surgical humidification therapy during laparoscopic surgery may minimise the incidence of adhesion formation.[23] Other techniques to reduce adhesion formation include the use of physical barriers such as films or gels, or broad-coverage fluid agents to separate tissues during healing following surgery.[21]

Robotic laparoscopic surgery

The process of minimally invasive surgery has been augmented by specialized tools for decades. For example, TransEnterix of Durham, North Carolina received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in October 2009 for its SPIDER Surgical System using flexible instruments and one incision in the navel area instead of several, allowing quicker healing for patients. Dr. Richard Stac of Duke University developed the process.[24][25]

In recent years, electronic tools have been developed to aid surgeons. Some of the features include:

- Visual magnification — use of a large viewing screen improves visibility

- Stabilization — Electromechanical damping of vibrations, due to machinery or shaky human hands

- Simulators — use of specialized virtual reality training tools to improve physicians' proficiency in surgery [26]

- Reduced number of incisions

There has been a distinct lack of disclosure regarding nano-scale developments in keyhole surgery and remote medicine, a "disparity of disclosure" which does not correlate with the rapid advancements in both the medical and nanotechnology fields over the last two decades.

Robotic surgery has been touted as a solution to underdeveloped nations, whereby a single central hospital can operate several remote machines at distant locations. The potential for robotic surgery has had strong military interest as well, with the intention of providing mobile medical care while keeping trained doctors safe from battle.

Non-robotic hand guided assistance systems

There are also user-friendly non robotic assistance systems that are single hand guided devices with a high potential to save time and money. These assistance devices are not bound by the restrictions of common medical robotic systems. The systems enhance the manual possibilities of the surgeon and his/her team, regarding the need of replacing static holding force during the intervention.

Some of the features are:

- The stabilisation of the camera picture because the whole static workload is conveyed by the assistance system.

- Some systems enable a fast repositioning and very short time for fixation of less than 0.02 seconds at the desired position. Some systems are lightweight constructions (18 kg) and can withstand a force of 20 N in any position and direction.

- The benefit – a physically relaxed intervention team can work concentrated on the main goals during the intervention.

- The potentials of these systems enhance the possibilities of the mobile medical care with those lightweight assistance systems. These assistance systems meet the demands of true solo surgery assistance systems and are robust, versatile, and easy to use.

History

It is difficult to credit one individual with the pioneering of the laparoscopic approach. In 1901, Georg Kelling of Dresden, Germany, performed the first laparoscopic procedure in dogs, and, in 1910, Hans Christian Jacobaeus of Sweden performed the first laparoscopic operation in humans.[27]

In the ensuing several decades, numerous individuals refined and popularized the approach further for laparoscopy. The advent of computer chip-based television cameras was a seminal event in the field of laparoscopy. This technological innovation provided the means to project a magnified view of the operative field onto a monitor and, at the same time, freed both the operating surgeon's hands, thereby facilitating performance of complex laparoscopic procedures. Prior to its conception, laparoscopy was a surgical approach with very few applications, mainly for purposes of diagnosis and performance of simple procedures in gynecologic applications.

The first publication on modern diagnostic laparoscopy by Raoul Palmer appeared in 1947,[28] followed by the publication of Hans Frangenheim and Kurt Semm. Hans Lindermann and Kurt Semm practised CO

2 hysteroscopy during the mid-1970s.

In 1972, Clarke invented, published, patented, presented, and recorded on film laparoscopic surgery, with instruments marketed by the Ven Instrument Company of Buffalo, New York.[29]

In 1975, Tarasconi, from the Department of Ob-Gyn of the University of Passo Fundo Medical School (Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil), started his experience with organ resection by laparoscopy (Salpingectomy), first reported in the Third AAGL Meeting, Hyatt Regency Atlanta, November 1976 and later published in The Journal of Reproductive Medicine in 1981.[30] This laparoscopic surgical procedure was the first laparoscopic organ resection reported in medical literature.

In 1981, Semm, from the gynecological clinic of Kiel University, Germany, performed the first laparoscopic appendectomy. Following his lecture on laparoscopic appendectomy, the president of the German Surgical Society wrote to the Board of Directors of the German Gynecological Society suggesting suspension of Semm from medical practice. Subsequently, Semm submitted a paper on laparoscopic appendectomy to the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, at first rejected as unacceptable for publication on the grounds that the technique reported on was "unethical," but finally published in the journal Endoscopy.[31] The abstract of his paper on endoscopic appendectomy can be found at here. Semm established several standard procedures that were regularly performed, such as ovarian cyst enucleation, myomectomy, treatment of ectopic pregnancy and finally laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (nowadays termed as cervical intra-fascial Semm hysterectomy). He also developed a medical instrument company Wisap in Munich, Germany, which still produces various endoscopic instruments of high quality. In 1985, he constructed the pelvi-trainer = laparo-trainer, a practical surgical model whereby colleagues could practice laparoscopic techniques. Semm published over 1000 papers in various journals.[4] He also produced over 30 endoscopic films and more than 20,000 colored slides to teach and inform interested colleagues about his technique. His first atlas, More Details on Pelviscopy and Hysteroscopy was published in 1976, a slide atlas on pelviscopy, hysteroscopy, and fetoscopy in 1979, and his books on gynecological endoscopic surgery in German, English, and many other languages in 1984, 1987, and 2002.

Prior to 1990, the only specialty performing laparoscopy on a widespread basis was gynecology, mostly for relatively short, simple procedures such as a diagnostic laparoscopy or tubal ligation. The introduction in 1990 of a laparoscopic clip applier with twenty automatically advancing clips (rather than a single load clip applier that would have to be taken out, reloaded and reintroduced for each clip application) made general surgeons more comfortable with making the leap to laparoscopic cholecystectomies (gall bladder removal). On the other hand, some surgeons continue to use the single clip appliers as they save as much as $200 per case for the patient, detract nothing from the quality of the clip ligation, and add only seconds to case lengths. It must be noted that both laparoscopy tubal ligations and cholecystectomies may be performed using suturing and tying, thus further reducing the expensive cost of single and multiclips (when compared to suture). Once again this may increase case lengths but costs are greatly reduced (ideal for developing countries) and widespread accidents of loose clips are eliminated.

See also

- Arthroscopic surgery

- Percutaneous (surgery)

- Invasiveness of surgical procedures

- Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES)

- Revision weight loss surgery

- Single port laparoscopy

References

- ↑ Mastery of Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgery W. Stephen, M.D. Eubanks; Steve Eubanks (Editor); Lee L., M.D. Swanstrom (Editor); Nathaniel J. Soper (Editor) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2nd Edition 2004

- ↑ "Training in diagnostic laparoscopy". Gfmer.ch. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ https://www.surgicalinstruments.com/surgical-instruments/surgical-instruments-browse-by-specialty/category/62240-laparoscopy

- ↑ http://www.bonati.com

- ↑ US patent 5203781, Bonati, Alfred O.; Ware, Philip, "Lumbar arthroscopic laser sheath", issued April 20, 1993

- ↑ Bhandarkar, Deepraj; Mittal, Gaurav; Shah, Rasik; Katara, Avinash; Udwadia, Tehemton E (January 1, 2011). "Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: How I do it?". Journal of Minimal Access Surgery. 7 (1): 17–23. ISSN 0972-9941. PMC 3002000

. PMID 21197237. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.72367.

. PMID 21197237. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.72367. - ↑ Walid MS, Heaton RL (2010). "Laparoscopy-to-laparotomy quotient in obstetrics and gynecology residency programs". Arch Gynecol Obstet. 283 (5): 1027–1031. PMID 20414665. doi:10.1007/s00404-010-1477-2.

- ↑ http://www.nycbariatrics.com/weight-loss-surgery-options/gastric-bypass

- ↑ Jimenez-Rodríguez, RM; Segura-Sampedro, JJ (February 2016). "Laparoscopic approach in gastrointestinal emergencies.". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (6).

- ↑ Journal of Indian Association of pediatric surgeons, 2010 October – December, pp. 122–126, accessible at http://www.jiaps.com

- ↑ Westebring-van der Putten EP; Goossens RHM; Jakimowicz JJ; Dankelman J (2008). "Haptics in Minimally Invasive Surgery – A Review". Minimally Invasive Therapy. 17 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1080/13645700701820242.

- ↑ A. G. Gallagher; N. McClure; J. McGuigan; K. Ritchie; N. P. Sheehy (2007). "An Ergonomic Analysis of the Fulcrum Effect in the Acquisition of Endoscopic Skills". Endoscopy. 1 (7): 617–620. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001366.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Anthony, Carpel Tunnel Surgery in Review, Beklind, 2009p.234

- ↑ Mayol, Julio; Garcia-Aguilar, Julio; Ortiz-Oshiro, Elena; De-Diego Carmona, Jose A.; Fernandez-Represa, Jesus A. (1997). "Risks of the Minimal Access Approach for Laparoscopic Surgery: Multivariate Analysis of Morbidity Related to Umbilical Trocar Insertion". World Journal of Surgery. 21 (5): 529–533. ISSN 0364-2313. doi:10.1007/PL00012281.

- ↑ Mirhashemi R, Harlow BL, Ginsburg ES, Signorello LB, Berkowitz R, Feldman S (September 1998). "Predicting risk of complications with gynecologic laparoscopic surgery". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (3): 327–31. PMID 9721764. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00209-9.

- ↑ Janie Fuller, DDS, (CAPT, USPHS), Walter Scott, Ph.D. (CAPT, USPHS), Binita Ashar, M.D., Julia Corrado, M.D. FDA, CDRH, "Laparoscopic Trocar Injuries: A report from a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) Systematic Technology Assessment of Medical Products (STAMP) Committee" Finalized: November 7, 2003

- ↑ http://encision.com/aem-technology/why-aem/

- ↑ Peng Y, Zheng M, Ye Q, Chen X, Yu B, Liu B (January 2009). "Heated and humidified CO

2 prevents hypothermia, peritoneal injury, and intra-abdominal adhesions during prolonged laparoscopic insufflations". J. Surg. Res. 151 (1): 40–7. PMID 18639246. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2008.03.039. - ↑ Alexander JI, Hull MG (March 1987). "Abdominal pain after laparoscopy: the value of a gas drain". Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 94 (3): 267–9. PMID 2952161. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02366.x.

- 1 2 Dörthe, Brüggmann; Garri Tchartchian; Markus Wallwiener; Karsten Münstedt; Hans-Rudolf Tinneberg; Andreas Hackethal (November 2010). "Intra-abdominal Adhesions – Definition, Origin, Significance in Surgical Practice, and Treatment Options". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 107 (44): 769–775. PMC 2992017

. PMID 21116396. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0769.

. PMID 21116396. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0769. - 1 2 3 DeWilde, Rudy Leon; Geoffrey Trew (September 2007). "Postoperative abdominal adhesions and their prevention in gynaecological surgery. Expert consensus position". Gynecological Surgery. 4 (3): 161–168. doi:10.1007/s10397-007-0338-x.

- ↑ Lower, A.M.; R.J.S. Hawthorn; D. Clark; J.H. Boyd; A.R. Finlayson; A.D. Knight; A.M. Crowe (2004). "Adhesion-related readmissions following gynaecological laparoscopy or laparotomy in Scotland: an epidemiological study of 24 046 patients". Human Reproduction. 19 (8): 1877–1885. PMID 15178659. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh321.

- ↑ Peng, Y; Zheng M; Ye Q; Chen X; Yu B; Liu B (Jan 2009). "Heated and Humidified CO2 prevents hypothermia, peritoneal injury, and intra-abdominal adhesions during prolonged laparoscopic insufflations.". J Surg Res. 151 (1): 40–7. PMID 18639246. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2008.03.039.

- ↑ Ranii, David (January 19, 2010). "TransEnterix ready to move forward". News & Observer. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ Hoyle, Amanda Jones (December 21, 2009). "TransEnterix, eyeing 50 new hires, moves to bigger office". Triangle Business Journal. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ Ahmed K, Keeling AN, Fakhry M, et al. (January 2010). "Role of virtual reality simulation in teaching and assessing technical skills in endovascular intervention". J Vasc Interv Radiol. 21 (1): 55–66. PMID 20123191. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2009.09.019.

- ↑ Journal of Endourology Hans Christian Jacobaeus: Inventor of Human Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy

- ↑ Palmer, R (1947). "Instrumentation et technique de la coelioscopie gynecologique.". Gynecol Obstet (Paris). 46 (4): 420–31. PMID 18917806.

- ↑ Clarke HC (April 1972). "Laparoscopy—new instruments for suturing and ligation". Fertil. Steril. 23 (4): 274–7. PMID 4258561.

- ↑ Tarasconi JC (October 1981). "Endoscopic salpingectomy". J Reprod Med. 26 (10): 541–5. PMID 6458700.

- ↑ Semm K (March 1983). "Endoscopic Appendectomy". Endoscopy. 15 (2): 59–64. PMID 6221925. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1021466.

External links

- Feder, Barnaby J., "Surgical Device Poses a Rare but Serious Peril" The New York Times, March 17, 2006

- Laparoscopy web information

- Laparoscopic surgeries

- World Association of Laparoscopic Surgeons

- World Journal of Laparoscopic Surgery