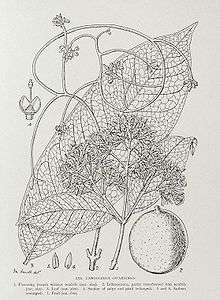

Landolphia owariensis

| Landolphia owariensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| L. owariensis wrapping around a fig tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Asterids |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Apocynaceae |

| Genus: | Landolphia |

| Species: | L. owariensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Landolphia owariensis P.Beauv., 1805 | |

Landolphia owariensis is a species of liana from the family Apocynaceae found in tropical Africa. Latex can be extracted from this plant for the manufacture of natural rubber.[1] Other names for this vine are eta, the white rubber vine and the Congo rubber plant.[2]

Description

When growing in savannah, Landolphia owariensis is an erect bush or small tree, but when growing among trees, it can develop into a woody vine with a stem that grows to a metre wide and 100 m (330 ft) long. The bark is rough, dark brown or greyish-brown, and often covered with pale yellow lenticels; it exudes a milky juice when damaged. The leaves grow in opposite pairs and are oblong, elliptical or obovate, up to 25 by 12 centimetres (10 by 5 in). The young leaves are reddish at first but the upper sides of the leaf blades later become dark green and glossy, with a pale midrib. The flowers are in terminal panicles. The peduncles and calyx lobes are clad in brown hairs, and the corolla tube and lobes are yellowish, pinkish or white. The flowers are followed by rounded, wrinkled fruit resembling oranges. These are juicy and slightly acid when ripe, with usually three seeds surrounded by soft, edible pulp.[3][4]

The main trunk soon divides into several stout stems which repeatedly branch as they clamber over their host trees. After the fruit have fallen, the stems elongate into tendrils which wist spirally and secure the vine to its host.[5]

Distribution and habitat

L. owariensis is native to the tropics of Africa, its range extending from Guinea in West Africa to Sudan and Tanzania in East Africa. When growing in open savannah it takes the form of a bush, but in forested areas it becomes a vine and can climb trees, reaching heights of 70 m (230 ft) or more. It has a rhizome which can survive bush fires, readily throwing up shoots which flower and fruit at a young age even before the twigs have become lignified.[1]

Uses

The fruit are gathered for human consumption, and are either eaten fresh or fermented into an alcoholic beverage.[3]

The latex used to be gathered for the manufacture of rubber. The latex coagulates rapidly after extraction, and one traditional method of collection was to make an incision on the stem and allow the latex to trickle onto the gatherer's hand and arm where it rapidly coagulated. When this process had been repeated several times, the rubber "sleeve" was unrolled off the arm.[5] The latex has been used to mix with the ground up seeds of Strophanthus to make arrow poison, and to glue the poison to the arrow-head. The latex is also used by itself as a birdlime to catch small birds and animals.[3]

L. owariensis has been used extensively in traditional medicine, with the leaves and stems being used as an anti-microbial, and in the treatment of venereal disease and of colic. Other uses include as a vermifuge, a purgative, an analgesic and an anti-inflammatory. A decoction prepared from the leaves is used against malaria and as a purgative; the bark is used against worms and an extract of the roots against gonorrhea. The latex that oozes from wounds can be drunk, or used as an enema to treat intestinal worms.[6]

History

In 1885, Leopold II established the Congo Free State under the auspices of the International Association of the Congo, by securing the European community's agreement with the claim that he was involved in humanitarian and philanthropic work.[7] To monopolize the resources of the entire Congo Free State, Leopold issued three decrees in 1891 and 1892 that reduced the native population to serfs. Collectively, these forced the natives to deliver all ivory and rubber, harvested or found, to state officers thus nearly completing Leopold's monopoly of the ivory and rubber trade. The rubber came from wild vines in the jungle, unlike the rubber from Brazil (Hevea brasiliensis), which was tapped from trees. To extract the rubber, instead of tapping the vines, the Congolese workers would slash them and lather their bodies with the rubber latex. When the latex hardened, it would be scraped off the skin in a painful manner, as it took off the worker's hair with it.[8] The Force Publique, the Free State's military, was used to enforce the rubber quotas. During the 1890s, the Force Publique's primary role was to enforce a system of corvée labour to promote the rubber trade. Armed with modern weapons and the chicotte—a bull whip made of hippopotamus hide—the Force Publique routinely took and tortured hostages, slaughtered families of rebels, and flogged and raped Congolese people. Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by death. Recalcitrant villages were burned and Force Publique soldiers were sometimes required to provide a severed hand from their victims as proof that they had not misused their weapons.[9] A Catholic priest quotes a man, Tswambe, speaking of a hated state official, Léon Fiévez, who ran a district along the river 500 kilometres (300 mi) north of Stanley Pool:

All blacks saw this man as the devil of the Equator...From all the bodies killed in the field, you had to cut off the hands. He wanted to see the number of hands cut off by each soldier, who had to bring them in baskets...A village which refused to provide rubber would be completely swept clean. As a young man, I saw [Fiévez's] soldier Molili, then guarding the village of Boyeka, take a net, put ten arrested natives in it, attach big stones to the net, and make it tumble into the river...Rubber causes these torments; that's why we no longer want to hear its name spoken. Soldiers made young men kill or rape their own mothers and sisters.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Landolphia owariensis". Useful tropical plants. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ Lost Crops of Africa. 3. National Academies Press. 2008. p. 277.

- 1 2 3 Neuwinger, Hans Dieter (1996). African Ethnobotany: Poisons and Drugs : Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology. CRC Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-3-8261-0077-2.

- ↑ Omino, Elizabeth (2002). Flora of Tropical East Africa: Apocynaceae. CRC Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-90-5809-409-4.

- 1 2 Journal of the Society of Arts. The Society. 1870. p. 89.

- ↑ Quattrocchi, Umberto (2012). CRC World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants. CRC Press. pp. 2206–2207. ISBN 978-1-4200-8044-5.

- ↑ Gifford, Paul (1971). France and Britain in Africa. Imperial Rivalry and Colonial Rule. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 221–260. ISBN 9780300012897.

- 1 2 Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 161–166. ISBN 9780547525730.

- ↑ Cawthorne, Nigel (1999). The World's Worst Atrocities. Octopus Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7537-0090-5.