Land Ordinance of 1785

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the United States Congress of the Confederation on May 20, 1785. It set up a standardized system whereby settlers could purchase title to farmland in the undeveloped west. Congress at the time did not have the power to raise revenue by direct taxation, so land sales provided an important revenue stream. The Ordinance set up a survey system that eventually covered over three-fourths of the area of the continental United States.[1]

The earlier Ordinance of 1784 was a resolution written by Thomas Jefferson (delegate from Virginia) calling for Congress to take action. The land west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River was to be divided into ten separate states.[2] However, the 1784 resolution did not define the mechanism by which the land would become states, or how the territories would be governed or settled before they became states. The Ordinance of 1785 put the 1784 resolution in operation by providing a mechanism for selling and settling the land,[3] while the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 addressed political needs.

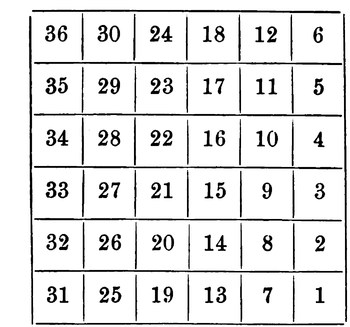

The 1785 ordinance laid the foundations of land policy until passage of the Homestead Act in 1862. The Land Ordinance established the basis for the Public Land Survey System. The initial surveying was performed by Thomas Hutchins. After he died in 1789, responsibility for surveying was transferred to the Surveyor General. Land was to be systematically surveyed into square townships, six miles (9.656 km) on a side. Each of these townships were sub-divided into thirty-six sections of one square mile (2.59 km²) or 640 acres. These sections could then be further subdivided for re-sale by settlers and land speculators.[4]

The ordinance was also significant for establishing a mechanism for funding public education. Section 16 in each township was reserved for the maintenance of public schools. Many schools today are still located in section sixteen of their respective townships, although a great many of the school sections were sold to raise money for public education. In later States, section 36 of each township was also designated as a "school section".[5][6][7]

The Point of Beginning for the 1785 survey was where Ohio (as the easternmost part of the Northwest Territory), Pennsylvania and Virginia (now West Virginia) met, on the north shore of the Ohio River near East Liverpool, Ohio. There is a historical marker just north of the site, at the state line where Ohio State Route 39 becomes Pennsylvania Route 68.

History

The Confederation Congress appointed a committee consisting of the following men:

- Thomas Jefferson (Virginia)

- Hugh Williamson (North Carolina)

- David Howell (Rhode Island)

- Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts)

- Jacob Read (South Carolina)

On May 7, 1784, the committee reported “An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of locating and disposing of lands in the western territories, and for other purposes therein mentioned.” The ordinance required the land be divided into “hundreds of ten geographical miles square, each mile containing 6086 and 4-10ths of a foot” and “sub-divided into lots of one mile square each, or 850 and 4-10ths of an acre”,[8] numbered starting in the northwest corner, proceeding from west to east, and east to west, consecutively. After debate and amendment, the ordinance was reported to Congress April 26, 1785. It required surveyors “to divide the said territory into townships seven miles square, by lines running due north and south, and others crossing these at right angles. — The plats of the townships, respectively, shall be marked into sections of one mile square, or 640 acres.” This is the first recorded use of the terms “township” and “section.”[9]

On May 3, 1785, William Grayson of Virginia made a motion seconded by James Monroe to change “seven miles square” to “six miles square.” The ordinance was passed on May 20, 1785. The sections were to be numbered starting at 1 in the southeast and running south to north in each tier to 36 in the northwest. The surveys were to be performed under the direction of the Geographer of the United States, (Thomas Hutchins).[9] The Seven Ranges, the privately surveyed Symmes Purchase, and, with some modification, the privately surveyed Ohio Company of Associates, all of the Ohio Lands were the surveys completed with this section numbering.[10]

The Act of May 18, 1796,[11] provided for the appointment of a surveyor-general to replace the office of Geographer of the United States, and that “sections shall be numbered, respectively, beginning with number one in the northeast section, and proceeding west and east alternately, through the township, with progressive numbers till the thirty-sixth be completed.” All subsequent surveys were completed with this boustrophedonical section numbering system, except the United States Military District of the Ohio Lands which had five mile (8 km) square townships as provided by the Act of June 1, 1796,[12] and amended by the Act of March 1, 1800.[9][13]

Howe and others give Thomas Hutchins credit for conceiving the rectangular system of lots of one square mile in 1764 while a captain in the Sixtieth, or, Royal American, Regiment, and engineer to the expedition under Col. Henry Bouquet to the forks of the Muskingum, in what is now Coshocton County, Ohio. It formed part of his plan for military colonies north of the Ohio, as a protection against Indians. The law of 1785 embraced most of the new system.[14] Treat, on the other hand, notes that tiers of townships were familiar in New England, and insisted on by the New England legislators.[15]

Public education

- Public Education in Land Grants in the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 Background:*

The Land Ordinance of 1785, adopted May 20, 1785 by the Continental Congress, set the stage for an organized and community-based westward expansion in the United States in the years after the American Revolution. The Land Ordinance of 1785, coming on the heels of the Ordinance of 1784, was the effort of a five-person committee led by Thomas Jefferson. The ordinance established a systematic and ubiquitous process for surveying, planning and selling townships in the western frontier. [There is no reference to "Education" in this section - other than the title. It should be removed, or updated and properly cited.]

Layout of townships

Each western township contained thirty-six square miles of land, planned as a square measuring six miles on each side, which was further subdivided into thirty six lots, each lot containing one square mile of land. The mathematical precision of the planning was the concerted effort of surveyors. Each township contained dedicated space for public education and other government uses, as five of the thirty six lots were reserved for government or public purposes. The thirty six lots of each township were numbered accordingly on each township's survey. The centermost land of each township corresponded to lot numbers 15, 16, 21 and 22 on the township survey, with lot number 16 dedicated specifically to public education. As the Land Ordinance of 1785 stated: "There shall be reserved the lot No. 16, of every township, for the maintenance of public schools within the said township."[16]

Knepper notes: “Sections number 8, 11, 26, and 29 in every township were reserved for future sale by the federal government when, it was hoped, they would bring higher prices because of developed land around them. Congress also reserved one third part of all gold, silver, lead, and copper mines to its own use, a bit of wishful thinking as regards Ohio lands.”[17] The ordinance also said “That three townships adjacent to Lake Erie be reserved, to be hereafter disposed of by Congress, for the use of the officers, men, and others, refugees from Canada, and the refugees from Nova Scotia, who are or may be entitled to grants of land under resolutions of Congress now existing.“ This was not possible, as the area next to Lake Erie was property of Connecticut, so the Canadians had to wait until the establishment of the Refugee Tract in 1798.[18]

Influence

Many historians recognize the influences of the colonial experience in the land ordinances of the 1780s.[19] The committees that formulated these ordinances were inspired by the individual colonial experiences of the states that they represented. The committees attempted to implement the best practices of such states to solve the task at hand.[20] The surveyed townships of the Land Ordinance of 1785, writes historian Jonathan Hughes, “represented an amalgam of the colonial experience and ideals.”[21] Two geographically and ideologically distinct colonial land systems were competing at such time in history – the New England system and the Southern system.[20] While the primary influence on the Land Ordinance of 1785 was the New England land system of the colonial era, marked by its emphasis on community development and systematic planning, the exceedingly individualistic Southern land system also played a role.

Even though Jefferson’s committee had a Southern majority, it recommended the New England survey system.[22] The highly planned and surveyed western townships established in the Land Ordinance of 1785, were heavily influenced by the New England settlements of the colonial era, particularly the land grant provisions of the Ordinances which dedicated land towards public education and other government uses. In colonial times, New England settlements contained dedicated public space for schools and churches, which often held a central role in the community. For instance, the 1751 royal charter for Marlboro Vermont provides: “one Shear [share] for the First Settled Minister one Shear for the benefit of the School forever.”[23] By time of the Land Ordinance of 1785 was enacted, the New England states had used land grants for over a century to support public education and build new schools. The clause in the Land Ordinance of 1785 which dedicated “Lot Number 16” of each western township for public education reflected this regional New England experience.[24]

In addition, the use of surveyors to precisely chart out the new townships in the westward expansion was directly influenced by the New England land system, which similarly relied on surveyors and local committees to clearly delineate property boundaries. Defined property boundary lines and an established land title system, provided colonials with a sense of security in their land ownership, by minimizing the likelihood of ownership or boundary disputes. This was an important consideration in the Land Ordinance of 1785. One of the primary purposes of the Ordinance was to raise funds for the increasingly insolvent government. Providing land speculators security in their purchases encouraged additional demand for the western lands. In addition, the organized and communal nature of the western settlements, allowed the government to reserve a number of well-defined plots of land for future government development. Since the rest of the township would have been developed by the time the government decided to develop such reserved lands, there was an already built-in assurance of land value appreciation for the reserved lands. This had the effect of increasing the value of government assets without much further investment by the government.

The New England land system, while the primary influence on the great land ordinances of the 1780s, was not the only land system influence. The Southern land system, marked by individualism and personal initiative, also helped shape the ordinance. While the New England land system was premised on community-based development, the Southern land system was premised on individual frontiersman appropriating undeveloped land to call their own. The Southern pioneer claimed property and the local surveyor would demarcate it for him. The system did not protect people from competing claims or set up an orderly chain of title. The process was called ‘indiscriminate location”. This system encouraged individuals to amass large plantations instead of settling into dense communal development. This system was supported by the use of slave labor.[25] Perhaps the committee’s resistance against indiscriminate location and support for limited and disciplined land settlement was an implicit attempt to create a structural barrier to developing a plantation economy that was dependent on slave labor. The committee could have been attempting to effectively eradicate slavery in the West after Jefferson failed to outlaw it in the Land Ordinance of 1784.

While the Land Ordinance of 1785 created a New England style land system, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 determined how the townships would be administered. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, like the Land Ordinance of 1785, was inspired by the New England colonial settlements, and manifested this influence by further encouraging the worship of religion and the spread of education. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stated, “Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”[26] However, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also contained Southern characteristics of municipal governance. The Southern influence can be felt in the Western townships in that once the federal land was dedicated to the particular township, the township was relatively free of the influence of the federal government, and the local municipality was left to govern itself. This manifested itself in public education as well. Once the land was dedicated, the actual development of the public schools was the responsibility of the local township or the particular state.[27] Although the great Ordinances of the 1780s set the framework for a national system of schools by dedicating land across the West, the devolved development and administration by the state and local government led to unique results.[28]

Motive

Retaining central land in each township ensured that these lands would create value for the federal government. Instead of disbursing funds to the new states to create public education systems dedicating a central lot in each township provided the new townships with the means to develop educational institutions without any transfer of funds. This was a practical and necessary way to achieve the committee’s goal in a pre-Constitution America. Aside from raising funds for a financially struggling government, the westward expansion outlined in the Land Ordinances of the 1780s also provided a framework for spreading democratic ideals. Jefferson proposed an article in the Ordinance of 1784 that would have outlawed slavery in the new states after the year 1800. However he could not amass enough votes to pass the anti-slavery article. Later Jefferson did succeed, however, in ensuring public funding of education by dedicating land to education in the Land Ordinance of 1785. Public education was an ideal already developed in the New England colonial settlements. New Englanders provided for public education in their land grants due to a belief that public education could be used to further unite the young nation and spread democratic ideals.[29]

The systematic and highly organized westward settlements, with their local governments and central square dedicated towards public education were a concerted effort to inspire civic duty and participation in the democratic process. Usher relates this initiative to “the Supreme Court in Cooper v. Roberts (1855), ‘plant in the heart of every community the same sentiments of grateful reverence for the wisdom, forecast, and magnanimous statesmanship of those who framed the institutions of these new States.” [30] The westward expansion therefore was not only a tool for raising much needed funds, but also a tool in a grand socializing experiment to inoculate the settlers to democratic ideals. The hope was that the unique planning of each township with a public school centrally located, coupled with the obligation of each township’s local citizens to take part in the civic process of governing the township, teaching and building the schools, and maintaining order, would instill the democratic ideals crucial to the nation’s success.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Vernon Carstensen, "Patterns on the American Land." Journal of Federalism, (19870 18#4 pp 31–39

- ↑ Richard P. McCormick, "The 'Ordinance' of 1784?," William and Mary Quarterly, Jan 1993, Vol. 50 Issue 1, pp 112–22

- ↑ Journal of Continental Congress, Vol. 28, p. 375, May 20, 1785 Library of congress

- ↑ C. Albert White, A History of the Rectangular Survey System (Bureau of Land Management, 1983)

- ↑ White, A History of the Rectangular Survey System

- ↑ Williamson 1880 : 226

- ↑ The Oregon Territory Act (August 14, 1848) 9 Stat. 323 initiated practice of setting aside section 36 for schools: Section 20 “And be it further enacted, That when the lands in the said Territory shall be surveyed under the direction of the Government of the United States, preparatory to bringing the same into market, sections numbered sixteen and thirty-six in each township in said Territory shall be, and the same is hereby, reserved for the purpose of being applied to schools in said Territory, and in the States and Territories hereafter to be erected out of the same.”

- ↑ Journal of Continental Congress, Vol. 27, p. 446, May 28, 1784 Library of congress

- 1 2 3 Higgins 1887 : 33–34, 78–82

- ↑ Peters 1918 : 58

- ↑ 1 Stat. 464 – Text of Act of May 18, 1796 Library of Congress

- ↑ 1 Stat. 490 – Text of Act of June 1, 1796 Library of Congress

- ↑ 2 Stat. 14 – Text of Act of March 1, 1800 Library of Congress

- ↑ Howe 1907 : 134

- ↑ Treat 1910 : 179–182

- ↑ http://moglen.law.columbia.edu/twiki/bin/view/AmLegalHist/PublicEducationInLandGrantsSGrenbaum

- ↑ Knepper 2002 : 9

- ↑ Knepper 2002 : 51

- ↑ See Payson Jackson Treat. The National Land System. William S Hein and Co., 2003. and Jonathan Hughes “The Great Land Ordinances.” Minnesota Legal History Project http://www.minnesotalegalhistoryproject.org/assets/hughes.pdf (accessed March 2013).

- 1 2 Treat, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Hughes, p.11

- ↑ Treat p.26

- ↑ Hughes, p.13

- ↑ David Carleton, Landmark Congressional Laws on Education. Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 2002. p. 15.

- ↑ See Treat p.25

- ↑ The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Article 3. http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=8 (Accessed March 2013).

- ↑ Alexandra Usher, “Public Schools in the Original Federal Land Grant Program” The Center on Education Policy; April 2011 p. 8 http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED518388&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED518388 (Accessed March 2013)

- ↑ Usher, p. 8.

- ↑ Carleton, p. 15

- ↑ Usher, p. 7

References and further reading

- Higgins, Jerome S. (1887). Subdivisions of the Public Lands, Described and Illustrated, with Diagrams and Maps. Higgins & Co.

- Howe, Henry (1907). Historical Collections of Ohio, The Ohio Centennial Edition. 1. The State of Ohio.

- Knepper, George W (2002). The Official Ohio Lands Book (PDF). State of Ohio.

- Peters, William E (1918). Ohio Lands and Their Subdivision. W.E. Peters.

- Treat, Payson Jackson (1910). The National Land System 1785–1820. E.B. Treat and Co.

- Williamson, James A.; Donaldson, Thomas (1880). The Public Domain. Its History, with Statistics. Government Printing Office.

- Johnson, Hildegard Binder. Order upon the Land: The U.S. Rectangular Land Survey and the Upper Mississippi Country (1977)

- Geib, George W.. "The Land Ordinance of 1785: A Bicentennial Review," Indiana Magazine of History, March 1985, Vol. 81 Issue 1, pp 1–13

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Library of Congress – Ordinance Text

- Indiana Historical Bureau – Ordinance Text

- Ohio History Central – Land Ordinance of 1785

- Bureau of Land Management – Principal Meridians and Base Lines Map

- The Great American Grid – 1785 Land Ordinance Diagram

- Photographs of the Principal Meridians