Lamia

The Lamia: In this 1909 painting by Herbert James Draper, Lamia has human legs and a snakeskin around her waist. There is also a small snake on her right forearm. | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Daemon |

| Similar creatures |

Empusa, Mormo |

| Mythology | Greek |

| Country | Born in Libya but roams throughout Europe |

In ancient Greek mythology, Lamia (/ˈleɪmiə/; Greek: Λάμια) was a beautiful queen of Libya who became a child-eating daemon. Aristophanes claimed her name derived from the Greek word for gullet (λαιμός; laimos), referring to her habit of devouring children.[1] Modern scholarship reconstructs a Proto-Indo European stem *lem-, "nocturnal spirit", whence also lemures.[2]

Mythology

In the myth, Lamia is a mistress of the god Zeus, causing Zeus' jealous wife, Hera, to kill all of Lamia's children and transform her into a monster that hunts and devours the children of others. Another version has Hera stealing all of Lamia's children and Lamia, who loses her mind from grief and despair, starts stealing and devouring others' children out of envy, the repeated monstrosity of which transforms her into a monster.

Some accounts say she has a serpent's tail below the waist.[3] This popular description of her is largely due to Lamia, a poem by John Keats composed in 1819.[4] Antoninus Liberalis uses Lamia as an alternate name for the serpentine drakaina Sybaris; however, Diodorus Siculus describes her as having nothing more than a distorted face.[5]

Later traditions referred to many lamiae; these were folkloric monsters similar to vampires and succubi that seduced young men and then fed on their blood.[6][7]

In later stories, Lamia was cursed with the inability to close her eyes so that she would always obsess over the image of her dead children. Some accounts (see Horace, below) say Hera forced Lamia to devour her own children. Myths variously describe Lamia's monstrous (occasionally serpentine) appearance as a result of either Hera's wrath, the pain of grief, the madness that drove her to murder, or—in some rare versions—a natural result of being Hecate's daughter.[8]

Zeus then gave her the ability to remove her eyes.[9] The purpose of this ability is unclear in Diodorus, but other versions state Lamia's ability to remove her eyes came with the gift of prophecy. Zeus did this to appease Lamia in her grief over the loss of her children and to let her rest since she could not close her eyes.

Horace, in Ars Poetica (l.340), imagines the impossibility of retrieving the living children she has eaten:

Neu pransae Lamiae vivum puerum extrahat alvo.

Alexander Pope translates the line:

Shall Lamia in our sight her sons devour,and give them back alive the self-same hour?

Stesichorus identifies a Lamia as the mother of Scylla.[10] Further passing references to Lamia were made by Strabo (i.II.8) and Aristotle (Ethics vii.5). Antoninus Liberalis identifies the dragon Sybaris with Lamia, another conflation.

Interpretations

Mothers throughout Europe used to threaten their children with the story of Lamia.[11] Leinweber states, "She became a kind of fairy-tale figure, used by mothers and nannies to induce good behavior among children."[12]

Many lurid details were conjured up by later writers, assembled in the Suda, expanded upon in Renaissance poetry and collected in Bulfinch and in Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable: Lamia was envious of other mothers and ate their children. She was usually female, but Aristophanes suggests a hermaphroditic phallus.[13] Leinweber notes, "By the time of Apuleius, not only were Lamia characteristics liberally mixed into popular notions of sorcery, but at some level the very names were interchangeable."[14] Nicolas K. Kiessling compared the lamia with the medieval succubus and Grendel's mother in Beowulf.[15]

Apuleius, in The Golden Ass, describes the witch Meroe and her sister as lamiae:[16] "The three major enchantresses of the novel—Meroe, Panthia and Pamphylia—also reveal many vampiric qualities generally associated with Lamiae," David Walter Leinweber has noticed.[17]

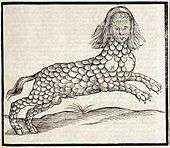

One interpretation posits the Lamia may have been a seductress, as in Philostratus' Life of Apollonius of Tyana, where the philosopher Apollonius reveals to the young bridegroom, Menippus, his hastily married wife is really a lamia, planning to devour him.[18] Some harlots were named "Lamia".[19] The connection between Demetrius Poliorcetes and the courtesan Lamia was notorious.[20][21][22] In a 1909 painting by Herbert James Draper, the Lamia who moodily watches the serpent on her forearm appears to represent a hetaera. Although the lower body of Draper's Lamia is human, he alludes to her serpentine history by draping a shed snake skin about her waist. In Renaissance emblems, Lamia has the body of a serpent and the breasts and head of a woman, like the image of hypocrisy.

Christian writers warned against the seductive potential of lamiae. In his 9th-century treatise on divorce, Hincmar, archbishop of Reims, listed lamiae among the supernatural dangers that threatened marriages, and identified them with geniciales feminae,[23] female reproductive spirits.[24]

John Keats described the Lamia in Lamia and Other Poems, presenting a description of the various colors of Lamia that was based on Burton's in The Anatomy of Melancholy.[25] The Keats story follows the general plotline of Philostratus, with Apollonius revealing Lamia's true nature before her wedding.

Modern folk traditions

In modern Greek folk tradition, the Lamia has survived and retained many of her traditional attributes.[26] John Cuthbert Lawson remarks "....the chief characteristics of the Lamiae, apart from their thirst for blood, are their uncleanliness, their gluttony, and their stupidity".[27] The contemporary Greek proverb, "της Λάμιας τα σαρώματα" ("the Lamia's sweeping"), epitomises slovenliness; and the common expression, "τό παιδί τό 'πνιξε η Λάμια" ("the child has been strangled by the Lamia"), explains the sudden death of young children.[27]

In popular culture

The English poet John Keats published his narrative poem "Lamia" in 1820.[28] The poem has influenced later works of Western literature. Elizabeth Barrett Browning's epic poem "Aurora Leigh" contains numerous references to Lamia, including Book One in which at times a portrait of her dead mother appears as a Lamia, and Book Six in which she repeatedly refers to Lady Waldemar as Lamia. Booker Prize winner A. S. Byatt's 1998 collection of short fiction, Elementals: Stories of Fire and Ice, contains a short story entitled "A Lamia in the Cévennes", which references Keats' poem.[29] The character Brawne Lamia appears in Dan Simmons' novels Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion. The works of John Keats feature heavily in the novels.[30][31] In Neil Gaiman's TV series and novel Neverwhere a character named Lamia is a "Velvet", a type of warmth-drinking vampire. The name is also given to the witch queen in the film adaptation of Gaiman's novel Stardust (a character who goes unnamed in the book).

Keats's poem also influenced British progressive-rock band Genesis and their track "The Lamia" from the 1974 double concept album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. The lyrics to the track, written by then lead vocalist Peter Gabriel, describe three snakelike creatures with female faces, roughly corresponding to Diodorus's description.

In the 2009 horror fantasy thriller film Drag Me to Hell, directed by Sam Raimi, the Lamia appears as the film's main antagonist character, described as a demon.

In John Connolly's book of short stories entitled Night Music: Nocturnes Volume 2,[32] the Lamia is a half-woman half snake or scorpion-like creature that helps victimized women gain revenge upon the men that rape them and escape the justice of the courts. It is unclear how the Lamia feeds upon the men, but she begins the ritual by forcing her snake-like tail down the throats of the men until their mouths split and the life leaves their bodies.

Different versions of lamias (known as domestic, a type human in appearance, or feral, a more bestial type) appear throughout the British fantasy series The Wardstone Chronicles, also known as The Last Apprentice series in the U.S.

See also

References

- ↑ Aristophanes, The Wasps, 1177.

- ↑ Polomé, Edgar C.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). "Spirit". In Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 538.

- ↑ Compare Typhon (Typhoeus), Echidna, the Gigantes and other archaic chthonic bogeys.

- ↑ Keats, "Lamia"

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Library of History xx. 41.

- ↑ Jøn, A. Asbjørn (2003). "Vampire Evolution". mETAphor. English Teachers Association of NSW (August): 19–23.

- ↑ Information on Lamia from the Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ Odyssey 12.124 and scholia, noted by Karl Kerenyi, Gods of the Greeks 1951:38 note 71.

- ↑ Bell, Women of Classical Mythology, drawing upon Diodorus Siculus XX.41; Suidas 'Lamia'; Plutarch 'On Being a Busy-Body' 2; Scholiast on Aristophanes' Peace 757; Eustathius on Odyssey 1714)

- ↑ Stesichorus Frag 220.

- ↑ Tertullian, Against Valentinius (ch.iii)

- ↑ Leinweber 1994:77.

- ↑ Aristophanes, Peace, l..758

- ↑ Leinweber 1994:78

- ↑ See Nicolas K. Kiessling, "Grendel: A New Aspect" Modern Philology 65.3 (February 1968):191–201.

- ↑ The Elizabethan translator William Adlington rendered lamiae as "hags", obscuring the reference for generations of readers. ([Apuleius], Metamorphoses [Harvard University Press] 1989 (Metamorphoses is more familiar to English-language readers as The Golden Ass.).

- ↑ Leinweber, "Witchcraft and Lamiae in 'The Golden Ass'" Folklore 105 (1994:77–82).

- ↑ Leinweber 1994:77f

- ↑ Kerényi 1951 p 40.

- ↑ See Plutarch, Life of Demetrius xxv.9

- ↑ See Aelian, Varia Historia XII.xvii.1

- ↑ See Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae III.lix.29.

- ↑ Hincmar, De divortio Lotharii ("On Lothar's divorce"), XV Interrogatio, MGH Concilia 4 Supplementum, 205, as cited by Bernadotte Filotas, Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature (Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2005, p. 305.

- ↑ In his 1628 Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, Du Cange made note of the geniciales feminae, and associated them with words pertaining to generation and genitalia; entry online.

- ↑ Keats made a note to this effect at the end of the first page in the fair copy he made: see William E. Harrold, "Keats's 'Lamia' and Peacock's 'Rhododaphne'" The Modern Language Review 61.4 (October 1966:579–584) p 579 and note with bibliography on this point.

- ↑ Lamia receives a section in Georgios Megas and Helen Colaclides, Folktales of Greece (Folktales of the World) (University of Chicago Prtes) 1970.

- 1 2 Lawson, Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion: A Study in Survivals (Cambridge University Press) 1910:175ff.

- ↑ http://www.bartleby.com/126/36.html Keats's poem Lamia

- ↑ "There's a Lamia in My Swimming Pool".

- ↑ "El ascenso de Endymion, de Dan Simmons".

- ↑ "Hyperion by Dan Simmons".

- ↑ http://www.johnconnollybooks.com

Sources

- Graves, R. (1955). "Lamia". Greek Myths. London: Penguin. pp. 205–06. ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- Karl Kerényi, 1951. The Gods of the Greeks pp 38–40. Edition currently in print is Thames & Hudson reissue, February 1980, ISBN 0-500-27048-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lamia (mythology). |