Superellipse

A superellipse, also known as a Lamé curve after Gabriel Lamé, is a closed curve resembling the ellipse, retaining the geometric features of semi-major axis and semi-minor axis, and symmetry about them, but a different overall shape.

In the Cartesian coordinate system, the set of all points (x, y) on the curve satisfy the equation

where n, a and b are positive numbers, and the vertical bars | | around a number indicate the absolute value of the number.

Specific cases

This formula defines a closed curve contained in the rectangle −a ≤ x ≤ +a and −b ≤ y ≤ +b. The parameters a and b are called the semi-diameters of the curve.

| The superellipse looks like a four-armed star with concave (inwards-curved) sides.

For n = 1/2, in particular, each of the four arcs is a segment of a parabola. |

The superellipse with n = 1⁄2, a = b = 1 | |

| The curve is a rhombus with corners (±a, 0) and (0, ±b). | ||

| The curve looks like a rhombus with those same corners but with convex (outwards-curved) sides.

The curvature increases without limit as one approaches its extreme points. |

The superellipse with n = 3⁄2, a = b = 1 | |

| The curve is an ordinary ellipse (in particular, a circle if a = b). | ||

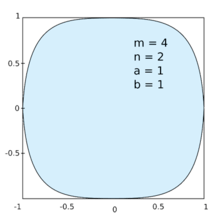

| The curve looks superficially like a rectangle with rounded corners.

The curvature is zero at the points (±a, 0) and (0, ±b). |

|

If n < 2, the figure is also called a hypoellipse; if n > 2, a hyperellipse.

When n ≥ 1 and a = b, the superellipse is the boundary of a ball of R2 in the n-norm.

The extreme points of the superellipse are (±a, 0) and (0, ±b), and its four "corners" are (±sa, ±sb), where (sometimes called the "superness"[1]).

Mathematical properties

When n is a nonzero rational number p/q (in lowest terms), then each quadrant of the superellipse is a plane algebraic curve. For positive n the order is pq; for negative n the order is 2pq. In particular, when a = b = 1 and n is an even integer, then it is a Fermat curve of degree n. In that case it is non-singular, but in general it will be singular. If the numerator is not even, then the curve is pasted together from portions of the same algebraic curve in different orientations.

The curve is given by the parametric equations

or

where the sign function is

Here is not the angle between the positive horizontal axis and the ray from the origin to the point, since the tangent of this angle equals y/x while in the parametric expressions y/x = (b/a)(tan 2/n ≠ tan

The area inside the superellipse can be expressed in terms of the gamma function, Γ(x), as

The pedal curve is relatively straightforward to compute. Specifically, the pedal of

is given in polar coordinates by[2]

Generalizations

The superellipse is further generalized as:

or

(Note that is not a physical angle of the figure, but just a parameter.)

History

The general Cartesian notation of the form comes from the French mathematician Gabriel Lamé (1795–1870), who generalized the equation for the ellipse.

Hermann Zapf's typeface Melior, published in 1952, uses superellipses for letters such as o. Thirty years later Donald Knuth would build the ability to choose between true ellipses and superellipses (both approximated by cubic splines) into his Computer Modern type family.

The superellipse was named by the Danish poet and scientist Piet Hein (1905–1996) though he did not discover it as it is sometimes claimed. In 1959, city planners in Stockholm, Sweden announced a design challenge for a roundabout in their city square Sergels Torg. Piet Hein's winning proposal was based on a superellipse with n = 2.5 and a/b = 6/5.[3] As he explained it:

- Man is the animal that draws lines which he himself then stumbles over. In the whole pattern of civilization there have been two tendencies, one toward straight lines and rectangular patterns and one toward circular lines. There are reasons, mechanical and psychological, for both tendencies. Things made with straight lines fit well together and save space. And we can move easily — physically or mentally — around things made with round lines. But we are in a straitjacket, having to accept one or the other, when often some intermediate form would be better. To draw something freehand — such as the patchwork traffic circle they tried in Stockholm — will not do. It isn't fixed, isn't definite like a circle or square. You don't know what it is. It isn't esthetically satisfying. The super-ellipse solved the problem. It is neither round nor rectangular, but in between. Yet it is fixed, it is definite — it has a unity.

Sergels Torg was completed in 1967. Meanwhile, Piet Hein went on to use the superellipse in other artifacts, such as beds, dishes, tables, etc.[4] By rotating a superellipse around the longest axis, he created the superegg, a solid egg-like shape that could stand upright on a flat surface, and was marketed as a novelty toy.

In 1968, when negotiators in Paris for the Vietnam War could not agree on the shape of the negotiating table, Balinski, Kieron Underwood and Holt suggested a superelliptical table in a letter to the New York Times.[3] The superellipse was used for the shape of the 1968 Azteca Olympic Stadium, in Mexico City.

Waldo R. Tobler developed a map projection, the Tobler hyperelliptical projection, published in 1973,[5] in which the meridians are arcs of superellipses.

The logo for news company The Local consists of a tilted superellipse matching the proportions of Sergels Torg. Three connected superellipses are used in the logo of the Pittsburgh Steelers.

In computing, mobile operating system iOS uses a superellipse curve for app icons, replacing the rounded corners style used up to version 6.[6]

See also

- Astroid, the superellipse with n = 2⁄3 and a = b, is a hypocycloid with four cusps.

- Deltoid curve, the hypocycloid of three cusps.

- Squircle, the superellipse with n = 4 and a = b, looks like "The Four-Cornered Wheel."

- Reuleaux triangle, "The Three-Cornered Wheel."

- Superformula, a generalization of the superellipse.

- Superquadrics and superellipsoids, the three-dimensional "relatives" of superellipses.

- Superelliptic curve, equation of the form Yn = f(X).

- Lp spaces

References

- ↑ Donald Knuth: The METAFONTbook, p. 126

- ↑ J. Edwards (1892). Differential Calculus. London: MacMillan and Co. p. 164.

- 1 2 Gardner, Martin (1977), "Piet Hein’s Superellipse", Mathematical Carnival. A New Round-Up of Tantalizers and Puzzles from Scientific American, New York: Vintage Press, pp. 240–254, ISBN 978-0-394-72349-5

- ↑ The Superellipse, in The Guide to Life, The Universe and Everything by BBC (27 June 2003)

- ↑ Tobler, Waldo (1973), "The hyperelliptical and other new pseudocylindrical equal area map projections", Journal of Geophysical Research, 78 (11): 1753–1759, Bibcode:1973JGR....78.1753T, doi:10.1029/JB078i011p01753.

- ↑ http://iosdesign.ivomynttinen.com/

- Barr, Alan H. (1983), Geometric Modeling and Fluid Dynamic Analysis of Swimming Spermatozoa, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Ph.D. dissertation using superellipsoids)

- Barr, Alan H. (1992), "Rigid Physically Based Superquadrics", in Kirk, David, Graphics Gems III, Academic Press, pp. 137–159 (code: 472–477), ISBN 978-0-12-409672-1

- Gielis, Johan (2003), Inventing the Circle: The Geometry of Nature, Antwerp: Geniaal Press, ISBN 978-90-807756-1-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Superellipse. |

- Sokolov, D.D. (2001) [1994], "Lamé curve", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- "Courbe de Lamé" at Encyclopédie des Formes Mathématiques Remarquables (in French)

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Superellipse". MathWorld.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Lame Curves", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- "Super Ellipse" on 2dcurves.com

- Superellipse Calculator & Template Generator

- C code for fitting superellipses