Chad Basin

The Chad Basin is the largest endorheic basin in Africa, centered on Lake Chad. It has no outlet to the sea and contains large areas of desert or semi-arid savanna. The drainage basin is roughly coterminous with the sedimentary basin of the same name, but extends further to the northeast and east. The basin spans seven countries, including most of Chad and a large part of Niger. The region has an ethnically diverse population of about 30 million people as of 2011, growing rapidly.

A combination of dams, increased irrigation, climate change, and reduced rainfall are causing water shortages, contributing to terrorism and the rise of Boko Haram in the region.[1] Lake Chad continues to shrink.

Geology

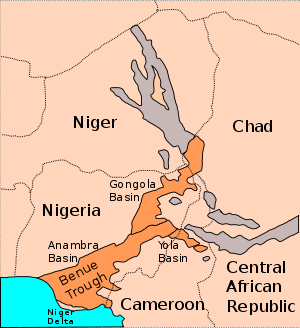

The geological basin, which is smaller than the drainage basin, is a Phanerozoic sedimentary basin formed during the plate divergence that opened the South Atlantic Ocean. The basin lies between the West African Craton and Congo Craton, and formed around the same time as the Benue Trough. It covers an area of about 2,335,000 square kilometres (902,000 sq mi).[2] It merges into the Iullemmeden Basin to the west at the Damergou gap between the Aïr and Zinder massifs.[3] The floor of the basin is made of Precambrian bedrock covered by more than 3,600 metres (11,800 ft) of sedimentary deposits.[2]

The basin may have resulted from the intersection of an "Aïr-Chad Trough" running NW-SE and a "Tibesti-Cameroon Trough" running NE-SW.[2] That is, the two deepest parts are an extension of the Benue Trough that runs northeast to the margin of the basin, and another extension running from below the present lake to below the Ténéré rift structure to the east of the Aïr massif. The southern part of the basin is underlain by another elongated depression.[3] This runs in an ENE direction and extends from the Yola arm of the Benue trough.[4]

At times, parts of the basin were below the sea. In the northeastern part of the Benue Trough where it enters the Chad Basin there are marine sediments from the Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma[lower-alpha 1]). These sediments seem to be considerably thicker towards the northeast. Boreholes under Maiduguri have found marine sediments 400 metres (1,300 ft) deep, lying over continental sediments 600 metres (2,000 ft) deep.[4] The sea seems to have retreated from the western part of the basin in the Turonian (93.5–89.3 Ma). In the Maastrichtian (72.1–66 Ma) the west was non-marine, but the southeast probably was still marine. No marine sediments have been found from the Paleocene (66–56 Ma).[4]

For most of the Quaternary, from 2.6 million years ago to the present, the basin seems to have been a huge, well-watered plain, with many rivers and water bodies, probably rich in plant and animal life. Towards the end of this period the climate became drier. Around 20,000-40,000 years ago, eolianite sand dunes began to form in the north of the basin.[4] During the Holocene, from 11,000 years ago until recently, a giant "Lake Mega-Chad" covered an area of more than 350,000 square kilometres (140,000 sq mi) in the basin.[5] It would have drained to the Atlantic Ocean via the Benue River. Stratigraphic records show that "Mega-Chad" varied in size as the climate changed, with a peak about 2,300 years ago. The remains of fish and molluscs from this period are found in what are now desert regions.[6]

Drainage basin extent

The Chad Basin covers almost 8% of the African continent, with an area of about 2,434,000 square kilometres (940,000 sq mi). It is ringed by mountains. The Aïr Mountains and the Termit Massif in Niger form the western boundary. To the northwest, in Algeria, are the Tassili n'Ajjer mountains, including the 2,158 metres (7,080 ft) Jebel Azao. The Tibesti Mountains to the north of the basin include Emi Koussi, the highest mountain in the Sahara at 3,415 metres (11,204 ft). The Ennedi Plateau lies to the northeast, rising to 1,450 metres (4,760 ft).[7] The Ouaddaï highlands lies the east.[6] They include the Marrah Mountains in Darfur at up to 3,088 metres (10,131 ft) in height. The Adamawa Plateau, Jos Plateau, Biu Plateau, and Mandara Mountains lie to the south.[7]

To the west the basin is separated by a watershed from the Niger River, and to the south it is separated by a basement dome from the Benue River.[8] Further east, watersheds separate it from the Congo Basin and the Nile.

The lowest part of the basin is not Lake Chad, but the Bodélé Depression, at a distance of 480 kilometres (300 mi) to the northeast of the lake. The Bodélé Depression is just 155 metres (509 ft) above sea level in its deepest portion, while the surface of Lake Chad is 275 metres (902 ft) above sea level.[7]

The basin spans parts of seven countries. These are:[9]

| Country | Independent | Area within basin (km2) | % of total area of basin | % of country in basin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 1962 | 93,451 | 3.9% | 3.9% |

| Cameroon | 1960 | 50,775 | 2.1% | 10.7% |

| Central African Republic | 1960 | 219,410 | 9.2% | 35.2% |

| Chad | 1960 | 1,046,196 | 43.9% | 81.5% |

| Niger | 1960 | 691,473 | 29.0% | 54.6% |

| Nigeria | 1960 | 179,282 | 7.5% | 19.4% |

| Sudan | 1956 | 101,048 | 4.2% | 4.0% |

| Total | 2,381,635 | 100% |

Climate and ecology

The northern half of the basin is desert, containing the Ténéré desert, Erg of Bilma and Djurab Desert. South of that is the Sahel zone, dry savanna and thorny shrub savanna. The main rivers include riparian forests, flooding savannas and wetland areas. In the far south there are dry forests.[7] Rainfall varies widely from year to year. The amount of annual rainfall is very low in the north of the basin, rising to 1,200 millimetres (47 in) in the south.[10]

As late as 2000, the basin has remained home to large populations of wildlife. In the Sahel these include antelopes such as the addax and dama gazelle, and in the savannah there are korrigum and red-fronted gazelle. The black crowned crane and other waterbirds are found in the wetlands. There are populations of elephants, giraffes, and lions. The western black rhinoceros was once common but is now extinct. Elephants almost became extinct by the end of the nineteenth century due to European and American demand for ivory, but stocks have since recovered.[11]

Water resources

Rivers

The seasonal Korama River in the south of Niger does not reach Lake Chad. Nigeria includes two sub-basins that drain into Lake Chad. The Hadejia - Jama'are - Yobe sub-basin in the north contains the Hadejia and Jama'are rivers, which supply the 6,000 square kilometres (2,300 sq mi) Hadejia-Nguru wetlands. They converge to form the Yobe, which defines the border between Niger and Nigeria for 300 kilometres (190 mi), flowing into Lake Chad. About .5 cubic kilometres (0.12 cu mi) of water reaches Lake Chad annually. Construction of upstream dams and growth in irrigation have reduced water flow, and the floodplains are drying up. The Yedseram - Ngadda sub-basin further south is fed by the Yedseram River and Ngadda River, which join to form a 80 square kilometres (31 sq mi) swamp to the southwest of the lake. There is no significant water flow from the swamp to the lake.[9]

The Central African Republic (CAR) contains the sources of the Chari and Logone rivers, which flow north into the lake. The volume of water entering Chad annually from the CAR has fallen from about 33 cubic kilometres (7.9 cu mi) before the 1970s to 17 cubic kilometres (4.1 cu mi) in the 1980s. A further 3 cubic kilometres (0.72 cu mi) to 7 cubic kilometres (1.7 cu mi) of water annually flows from Cameroon into Chad via the Logone River. The Chari-Logone system accounts for about 95% of the water entering Lake Chad.[9]

Aquifers

The basin in the Nigerian section contains an upper aquifer of Early Pleistocene alluvial deposits that are often covered by recent sand dunes, varying in thickness from 15 to 100 metres (49 to 328 ft). It consists of interbedded sands, clays and silts, with discontinuous clay lenses. The aquifer recharges from run-off and rainfall. The local people access the water with hand-dug wells and shallow boreholes, and use it for domestic use, growing vegetables and watering their livestock. Below this aquifer, separated from it by a sequence of grey to bluish-grey clays from the Zanclean, is a second aquifer at a depth of 240 to 380 metres (790 to 1,250 ft). Due to heavy pumping, since the start of the 1980s the water levels in both aquifers has been lowered, and some wells no longer function.[12] There is a third, much lower, aquifer in Bima Sandstones that lies at a depth of 2,700 to 4,600 metres (8,900 to 15,100 ft).[13]

Management

The Lake Chad Basin Commission was set up in 1964 by Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, the four countries that contain parts of Lake Chad.[10] About 20% of the basin, lying in these countries, is called the Conventional Basin. The Lake Chad Basin Commission manages use of water and other natural resources in this area.[9] Although the lake fluctuates considerably in size from one year to another, the general trend has been for water levels to drop. There has been a proposal to supply water from the Congo Basin via a canal 2,400 kilometres (1,500 mi) long, but major political, technical, and economic challenges would have to be overcome to make this practical.[9]

People

History

Humans have lived in the inner Chad Basin from at least eight thousand years ago, and were engaging in agriculture and livestock management around the lake by 1000 BC. Permanent villages were established to the south of the lake by 500 BC at the start of the Iron Age.[14] The Chad Basin contained important trade routes to the east and to the north across the Sahara.[9] By the 5th century AD camels were being used for trans-Saharan trade via the Fezzan, or to the east via Darfur, where slaves and ivory were exchanged for salt, horses, glass beads, and, later, firearms.[15] After the Arabs took over North Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries, the Chad Basin became increasingly linked to the Muslim world.[14]

Trade and improved agricultural techniques supported more sophisticated societies, leading to the early kingdoms of the Kanem Empire, the Wadai Empire, and the Sultanate of Bagirmi.[15] Kanem rose in the 8th century in the region to the north and east of Lake Chad. The Sayfuwa dynasty that ruled this kingdom had adopted Islam by the 12th century.[14] The Kanem empire went into decline, shrank, and in the 14th century was defeated by Bilala invaders from the Lake Fitri region.[16] The Kanuri people led by the Sayfuwa migrated to the west and south of the lake, where they established the Bornu Empire. By the late 16th century the Bornu empire had expanded and recaptured the parts of Kanem that had been conquered by the Bilala.[17] Satellite states of Bornu included the Sultanate of Damagaram in the west and Baguirmi to the southeast of Lake Chad.

The Tunjur people founded the Wadai Empire to the east of Bornu in the 16th century. In the 17th century, the Maba people revolted and established a Muslim dynasty. At first, Wadai paid tribute to Bornu and Durfur, but by the 18th century Wadai was fully independent and had become an aggressor against its neighbors.[15] To the west of Bornu, by the 15th century the Kingdom of Kano had become the most powerful of the Hausa Kingdoms, in an unstable truce with the Kingdom of Katsina to the north.[18] Both of these states adopted Islam in the 15th and 16th centuries.[19] Both were absorbed into the Sokoto Caliphate during the Fulani War of 1805, which threatened Bornu itself.[20]

During the Berlin Conference in 1884-85 Africa was carved up between the European colonial powers, defining boundaries that are largely intact with today's post-colonial states.[21] On 5 August 1890 the British and French concluded an agreement to clarify the boundary between French West Africa and what would become Nigeria. A boundary was agreed along a line from Say on the Niger to Barruwa on Lake Chad, but leaving the Sokoto Caliphate in the British sphere.[22] Parfait-Louis Monteil was given charge of an expedition to discover where this line actually ran.[23] On 9 April 1892 he reached Kukawa on the shore of the lake.[24] Over the next twenty years a large part of the Chad Basin was incorporated by treaty or by force into French West Africa. On 2 June 1909 the Wadai capital of Abéché was occupied by the French.[25] The remainder of the basin was divided by the British in Nigeria who took Kano in 1903,[26] and the Germans in Kameroun. The countries of the basin regained their independence between 1956 and 1962, retaining the colonial administrative boundaries.

Population

As of 2011, over 30 million people lived in the Chad Basin. The population is growing rapidly.[9] Ethnic groups include Kanuri, Maba, Buduma, Hausa, Kanembu, Kotoko, Bagger, Haddad, Kuri, Fulani and Manga. The largest cities are Kano and Maiduguri in Nigeria, Maroua in Cameroon, N'Djamena in Chad and Diffa in Niger.[7]

Economy

The main economic activities are farming, herding and fishing.[9] At least 40% of the rural population of the basin lives in poverty and routinely face chronic food shortages.[27] Crop production based on rain is possible only in the southern belt. Flood recession agriculture is practiced around Lake Chad and in the riverine wetlands.[10] Nomadic herders migrate with their animals into the grasslands of the northern part of the basin for a few weeks during each short rainy season, where they intensively graze the highly nutritious grasses. When the dry season starts they move back south, either to grazing lands around the lakes and floodplains, or to the savannas further to the south.[28]

In the 2000-01 period, fisheries in the Lake Chad basin provided food and income to more than 10 million people, with a harvest of about 70,000 tons.[27] Fisheries have traditionally been managed by a system where each village has recognized rights over a defined part of the river, wetland or lake, and fishers from elsewhere must seek permission and pay a fee to use this area. The governments only enforced rules and regulations to a limited extent.[29] Fishery management practices vary. For example, on the Katagum river in Jigawa State, Nigeria, a village will have a water management council that collects a portion of each fisherman's catch and redistributes it among the villagers, or sells it and used the proceeds for communal projects.[30] Local governments and traditional authorities are increasingly engaged in rent-seeking, collecting license fees with the help of the police or army.[31]

References

Notes

- ↑ Ma: Million years ago

Citations

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Lake Chad: Climate change fosters terrorism | Africa | DW | 07.12.2015". DW.COM. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- 1 2 3 Obaje 2009, p. 69.

- 1 2 Wright 1985, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 Wright 1985, p. 95.

- ↑ Schuster, Roquin & Duringer 2005, p. 1821.

- 1 2 Chad Basin: Britannica.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Geography: Lake Chad Basin Commission.

- ↑ Haruna, Maigari & Tahir 2012, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Lake Chad basin: FAO.

- 1 2 3 Rangeley, Thiam & Anderson 1994, p. 49.

- ↑ Kenmore 2004, p. 228.

- ↑ Obaje 2009, p. 71.

- ↑ Obaje 2009, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Decorse 2001, p. 103.

- 1 2 3 Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 254.

- ↑ Falola 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ Falola 2008, p. 27.

- ↑ Falola 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ Falola 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ Udo 1970, p. 178.

- ↑ Harlow 2003, p. 139.

- ↑ Hirshfield 1979, p. 26.

- ↑ Hirshfield 1979, p. 37-38.

- ↑ Lengyel 2007, p. 170.

- ↑ Mazenot 2005, p. 352.

- ↑ Falola 2008, p. 105.

- 1 2 Kenmore 2004, p. 220.

- ↑ Kenmore 2004, p. 230.

- ↑ Kenmore 2004, p. 215.

- ↑ Kenmore 2004, p. 217.

- ↑ Kenmore 2004, p. 218.

Sources

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. (2010). Encyclopaedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- "Chad Basin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- Decorse, Christopher R. (2001). West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade: Archaeological Perspectives. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7185-0247-8. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Falola, Toyin (2008-04-24). A History of Nigeria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-47203-6. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- "Geography". Lake Chad Basin Commission. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- Harlow, Barbara (2003). "Conference of Berlin (1884–1885)". Colonialism. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Haruna, Ahmed Isah; Maigari, A. S.; Tahir, M. L.; Mamman, Y. D.; Gusikit, R. B. (2012-12-21). Detrital Gypsum Forms in the Nigerian (Southern) Sector of Chad Basin: A Criteria for interpretation in Nigeria’s inland basins: Implication of Detrital Gypsum Forms in Sedimentary Basins. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-656-33912-0. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Hirshfield, Claire (1979). The diplomacy of partition: Britain, France, and the creation of Nigeria, 1890–1898. Springer. ISBN 90-247-2099-0. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Kenmore, Peter Ervin (2004). The Future is an Ancient Lake: Traditional Knowledge, Biodiversity and Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Lake Chad Basin Ecosystems. Food & Agriculture Org. p. 215. ISBN 978-92-5-105064-4. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Lengyel, Emil (2007-03-01). Dakar - Outpost of Two Hemispheres. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4067-6146-7. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Mazenot, Georges (2005). Sur le passé de l'Afrique Noire. Editions L'Harmattan. p. 352. ISBN 978-2-296-59232-2. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Obaje, Nuhu George (2009-08-12). Geology and Mineral Resources of Nigeria. Springer. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-540-92684-9. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Rangeley, Robert; Thiam, Bocar M.; Anderson, Randolph A.; Lyle, Colin A. (1994). International river basin organizations in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Publications. ISBN 978-0-8213-2871-2. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Schuster, Mathieu; Roquin, Claude; Duringer, Philippe; Brunet, Michel; Caugy, Matthieu; Fontugne, Michel; Mackaye, Hassan Taïsso; Vignaud, Patrick; Ghienne, Jean-François (September 2005). "Holocene Lake Mega-Chad palaeoshorelines from space". Quaternary Science Reviews. 24 (16–17). doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.02.001. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- "The Lake Chad basin". FAO. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- Udo, Reuben K. (1970). Geographical regions of Nigeria. University of California Press. GGKEY:7F4FLYR0FS5. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- Wright, J.B. (1985-11-30). Geology and Mineral Resources of West Africa. Springer. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-04-556001-1. Retrieved 2013-05-06.