Laetentur Caeli

| Laetentur Caeli Latin : Let the Heavens Rejoice Encyclical letter of Pope Eugene IV | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date | 6 July 1439 |

| Argument | Reunited the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches |

| Encyclical number | of the pontificate |

| Text | |

Laetentur Caeli: Bulla Unionis Graecorum[1][note 1] (English: Let the Heavens Rejoice:[2] Bull of Union with the Greeks) was a papal bull issued on 6 July 1439[1] by Pope Eugene IV at the Council of Ferrara-Florence. It officially reunited the Roman Catholic Church with the Eastern Orthodox Churches, temporarily ending the Great Schism; however, it was repudiated by most eastern bishops shortly thereafter.[3] The incipit of the bull (also used as its title) is derived from Psalms 95:11[1] in the Vulgate Bible.

Political background

In 1439 the Byzantine Empire was on the verge of collapse, retaining little more than the city of Constantinople, as the Ottoman Empire swept into Europe.[2] During the reign of John V Palaiologos in the preceding century, the Byzantine Emperor had issued pleas to the West for aid in exchange for a union of the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches; the Papacy had been unmoved by these appeals,[4] as had been King Louis I of Hungary.[5] In 1369, after the fall of Adrianople to the Ottomans, John V had again issued a plea for help, hastening to Rome and publicly converting to Roman Catholicism.[4] Help had not come, and John V was instead forced to become a vassal of Ottoman Sultan Murad I.[4] A brief respite from Ottoman control later came as Timur pressured the Ottomans on the east, but by the 1420s Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaiologos again acutely felt the need for assistance from the West. He again made the same plea his predecessor had, travelling with a delegation to the Council of Ferrara-Florence to reconcile with the Western Church. He consulted with Neoplatonist philosopher Gemistus Pletho, who advised him that the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox delegations should have equal voting power at the Council;[6] nonetheless, the Emperor was under far more pressure to bring about a union than was the Pope. In order to help the Russian Orthodox Church unite with the Western Church, John VIII appointed Isidore of Kiev as Metropolitan of Kiev in 1436 against the wishes of Vasily II, Grand Prince of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[7]

Theological background

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches had developed several theological differences in the course of the Great Schism of 1054 and the centuries following. The chief difference revolved around the insertion of the word Filioque (English: and the Son) into the Latin version of the Nicene Creed by the Roman Catholic Church, which Orthodox bishops had refused to accept.[8] Thus, Eastern Orthodox dogma held that the Holy Spirit proceeded from God the Father, whereas Roman Catholic dogma held that it proceeded from both the Father and the Son.[8] The Eastern bishops at the Council of Florence emphatically denied that even an ecumenical council had the power to add anything to the creed.[9] A second central issue was that of Papal supremacy, which the Orthodox bishops had also rejected.[2] Also important was the issue of the doctrine of Purgatory, which the Eastern churches similarly rejected, and the issue of leavening, wherein the Orthodox Churches used leavened bread for the Eucharist while the Roman Catholics used unleavened bread.

Council of Florence and Laetentur Caeli

Pope Eugenius IV, Laetentur Caeli, opening sentences.

The 700 Eastern Orthodox delegates at the Council of Ferrara-Florence were maintained at the Pope’s expense.[10] Initially, Eastern Orthodox Patriarch Joseph II of Constantinople was in attendance, but when he died before the council ended, Emperor John VIII largely took Church matters into his own hands.[11] To this end, he appointed the pro-union Metrophanes II of Constantinople as Joseph II’s successor. In the summer of 1439 the council was moved from Ferrara to Florence because, at the instigation of Cosimo de' Medici, Florence offered to pay to maintain the Greek delegates, whom the Papacy was struggling to support.[10]

Since the Roman Catholic West held all of the bargaining power given John VIII’s desperate situation, the union of the churches was a simple matter for John: the Emperor ordered the Eastern representatives to accept the Western doctrines of the Filioque, Papal supremacy, and Purgatory, as Eugene IV asked.[11] In return, Eugene pledged to provide military assistance for the defence of Constantinople and to encourage the King of Germany Albrecht II to war against the Ottomans.[12] On 6 July 1439 the Emperor and all of the present bishops except one assented,[11] signing their names to Eugene’s Articles of Union. The day was proclaimed a public holiday in Florence, the Day of Union, and triumphal ceremonies were held.[10] Eugene IV then officially proclaimed the union in the form of a bull, Laetentur Coeli.[10] The bull was read from the pulpit of the Florence Cathedral by a Greek, Basilios Bessarion, and a Latin, Julian Cesarini.[8]

Laetentur Caeli contained the first formal conciliar definition of Papal primacy.[13] It has been suggested that Eugenius IV insisted on this because his primacy was at the time being threatened by a rival Antipope, Felix V, and the Conciliar Movement at the Council of Basle.[12] The bull mentioned no differences between Eastern and Western understandings of the Papacy but rather simply restated the Western position.[14] On the subject of the Filioque, it took a similar tone, emphasizing the commonalities between the theologies of the East and West but clearly siding with the Roman Catholic position without even mentioning Eastern Orthodox objections.[14] On the subject of bread, the bull provided for either unleavened or leavened bread to be used according to local custom.[1] The doctrine of Purgatory and the effectiveness of prayer for those in Purgatory were affirmed,[1] again according to the Roman Catholic doctrine. Finally, the bull defined the order of primacy among the patriarchs of the pentarchy as being Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and lastly Jerusalem.[1]

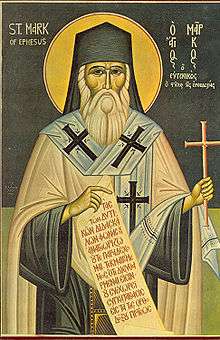

The lone dissenting voice against the bull was that of Mark of Ephesus, who refused to compromise on either the Filioque or Purgatory and held that Rome continued in heresy and schism.[11] Reportedly, upon seeing that Mark’s signature was missing, Eugene IV responded, “And so we have accomplished nothing.”[11] Nonetheless the union was to proceed, and representatives from the Vatican would be sent to Constantinople to see how it was being carried out.[11]

English Text

Council of Florence (XVII Ecumenical), Session 6 — 6 July 1439

[Definition of the holy ecumenical synod of Florence, presided by H.H. Pope Eugenius IV]

Eugenius, bishop, servant of the servants of God, for an everlasting record. With the agreement of our most dear son John Palaeologus, illustrious emperor of the Romans, of the deputies of our venerable brothers the patriarchs and of other representatives of the eastern church, to the following.

Let the heavens be glad and let the earth rejoice. For, the wall that divided the western and the eastern church has been removed, peace and harmony have returned, since the corner-stone, Christ, who made both one, has joined both sides with a very strong bond of love and peace, uniting and holding them together in a covenant of everlasting unity. After a long haze of grief and a dark and unlovely gloom of long-enduring strife, the radiance of hoped-for union has illuminated all.

Let Mother Church also rejoice. For she now beholds her sons hitherto in disagreement returned to unity and peace, and she who hitherto wept at their separation now gives thanks to God with inexpressible joy at their truly marvellous harmony. Let all the faithful throughout the world, and those who go by the name of Christian, be glad with mother catholic church. For behold, western and eastern fathers after a very long period of disagreement and discord, submitting themselves to the perils of sea and land and having endured labours of all kinds, came together in this holy ecumenical council, joyful and eager in their desire for this most holy union and to restore intact the ancient love. In no way have they been frustrated in their intent. After a long and very toilsome investigation, at last by the clemency of the holy Spirit they have achieved this greatly desired and most holy union. Who, then, can adequately thank God for his gracious gifts?' Who would not stand amazed at the riches of such great divine mercy? Would not even an iron breast be softened by this immensity of heavenly condescension?

These truly are works of God, not devices of human frailty. Hence they are to be accepted with extraordinary veneration and to be furthered with praises to God. To you praise, to you glory, to you thanks, O Christ, source of mercies, who have bestowed so much good on your spouse the catholic church and have manifested your miracles of mercy in our generation, so that all should proclaim your wonders. Great indeed and divine is the gift that God has bestowed on us. We have seen with our eyes what many before greatly desired yet could not behold.

For when Latins and Greeks came together in this holy synod, they all strove that, among other things, the article about the procession of the holy Spirit should be discussed with the utmost care and assiduous investigation. Texts were produced from divine scriptures and many authorities of eastern and western holy doctors, some saying the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, others saying the procession is from the Father through the Son. All were aiming at the same meaning in different words. The Greeks asserted that when they claim that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father, they do not intend to exclude the Son; but because it seemed to them that the Latins assert that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son as from two principles and two spirations, they refrained from saying that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. The Latins asserted that they say the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son not with the intention of excluding the Father from being the source and principle of all deity, that is of the Son and of the holy Spirit, nor to imply that the Son does not receive from the Father, because the holy Spirit proceeds from the Son, nor that they posit two principles or two spirations; but they assert that there is only one principle and a single spiration of the holy Spirit, as they have asserted hitherto. Since, then, one and the same meaning resulted from all this, they unanimously agreed and consented to the following holy and God-pleasing union, in the same sense and with one mind.

In the name of the holy Trinity, Father, Son and holy Spirit, we define, with the approval of this holy universal council of Florence, that the following truth of faith shall be believed and accepted by all Christians and thus shall all profess it: that the holy Spirit is eternally from the Father and the Son, and has his essence and his subsistent being from the Father together with the Son, and proceeds from both eternally as from one principle and a single spiration. We declare that when holy doctors and fathers say that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son, this bears the sense that thereby also the Son should be signified, according to the Greeks indeed as cause, and according to the Latins as principle of the subsistence of the holy Spirit, just like the Father.

And since the Father gave to his only-begotten Son in begetting him everything the Father has, except to be the Father, so the Son has eternally from the Father, by whom he was eternally begotten, this also, namely that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Son.

We define also that the explanation of those words "and from the Son" was licitly and reasonably added to the creed for the sake of declaring the truth and from imminent need.

Also, the body of Christ is truly confected in both unleavened and leavened wheat bread, and priests should confect the body of Christ in either, that is, each priest according to the custom of his western or eastern church. Also, if truly penitent people die in the love of God before they have made satisfaction for acts and omissions by worthy fruits of repentance, their souls are cleansed after death by cleansing pains; and the suffrages of the living faithful avail them in giving relief from such pains, that is, sacrifices of masses, prayers, almsgiving and other acts of devotion which have been customarily performed by some of the faithful for others of the faithful in accordance with the church's ordinances.

Also, the souls of those who have incurred no stain of sin whatsoever after baptism, as well as souls who after incurring the stain of sin have been cleansed whether in their bodies or outside their bodies, as was stated above, are straightaway received into heaven and clearly behold the triune God as he is, yet one person more perfectly than another according to the difference of their merits. But the souls of those who depart this life in actual mortal sin, or in original sin alone, go down straightaway to hell to be punished, but with unequal pains. We also define that the holy apostolic see and the Roman pontiff holds the primacy over the whole world and the Roman pontiff is the successor of blessed Peter prince of the apostles, and that he is the true vicar of Christ, the head of the whole church and the father and teacher of all Christians, and to him was committed in blessed Peter the full power of tending, ruling and governing the whole church, as is contained also in the acts of ecumenical councils and in the sacred canons.

Also, renewing the order of the other patriarchs which has been handed down in the canons, the patriarch of Constantinople should be second after the most holy Roman pontiff, third should be the patriarch of Alexandria, fourth the patriarch of Antioch, and fifth the patriarch of Jerusalem, without prejudice to all their privileges and rights.

Aftermath

In the West, Pope Eugenius IV conducted further negotiations in an attempt to extend the union. He signed an agreement with the Armenians on 22 November 1439, and with a part of the Jacobites of Syria in 1443, and in 1445 he received the Nestorians and the Maronites.[15] These unions proved unstable and mostly failed to last. In the spring of 1442 the Papacy began planning a crusade by both land and sea against the Ottomans from Hungary and the Mediterranean to fulfil the Pope’s pledges.[12] These plans were initially slowed by a civil war in Hungary.[12] On 1 January 1443, Eugene IV finally proclaimed an official crusade.[12] Władysław III of Poland, now King of Hungary as well, agreed, but could not find support among his Polish nobles because they supported the Conciliar Movement against the Pope.[12] Władysław nonetheless undertook the crusade with Hungarian troops and was killed in the Battle of Varna within a year, ending the attempt.[12] Constantinople could no longer expect the West’s military support.[12]

In the East, John VIII, Mark of Ephesus, and the rest of the Eastern hierarchs returned to Constantinople on 1 February 1440.[11] They soon found that the Byzantine people and the monks of Mount Athos, rallying around Mark, largely rejected the union.[7][8][11] The Uniate bishops in opposition to Mark attested his resistance: “Having returned to Constantinople, Ephesus disturbed and confused the Eastern Church by his writings and addresses directed against the decrees of the Council of Florence.”[11] Opinion among the bishops in Russia, contrary to those in Constantinople, remained with Mark, and by 1443 most Russian patriarchs repudiated the Council of Florence and the union of the churches.[11] Thus Isidore of Kiev was arrested at the command of Vasily II upon his return to Moscow and convicted of apostasy, after which he was imprisoned; he then escaped and fled to Rome to become a cardinal.[7][8] He returned to Constantinople in 1452 to celebrate the union but was forced to flee to Rome again as the city fell to the Ottomans.[7] Meanwhile, in 1448, seeking to escape any unionist influence, the Russian Orthodox Church declared itself autocephalous.[8]

The Venetian and Genoan governments ensured that no significant support from the West was forthcoming to Constantinople, supporting the Ottomans against the Byzantines.[8] With the fall of Constantinople the last prospects of the union, too, fell. The new Ottoman rulers wanted to prevent the conquered Byzantines from appealing to the West, so Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror appointed the anti-union Gennadius Scholarius as Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople; he immediately renounced the Filioque.[8] The Great Schism was renewed.

Notes

- ↑ Sometimes also spelled as Laetentur Coeli, Laetantur Caeli, Lætentur Cæli, Lætentur Cœli, or Lætantur Cæli, and occasionally referred to as the Act of Union.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pope Eugenius IV. Laetentur Caeli: Bulla Unionis Graecorum. 6 July 1439. Accessible at

- 1 2 3 Lyttle, Charles H. "Odd Moments and Papal Bulls" in The Christian Register, Vol. 91. p. 854. 5 September 1912.

- ↑ Davies, Norman. Europe: A History. p.446-448. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1996. ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- 1 2 3 Mango, Cyril. The Oxford History of Byzantium. 1st ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2002

- ↑ Küküllei János: Lajos király krónikája, Névtelen szerző: Geszta Lajos királyról; Osisris Kiadó, Budapest, 2000. (Millenniumi Magyar Történelem)

- ↑ Merry, Bruce (2002) "George Gemistos Plethon (c. 1355/60–1452)" in Amoia, Alba & Knapp, Bettina L., Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- 1 2 3 4 Isidore of Kiev, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008, O.Ed.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hamerman, Nora. The Council of Florence: The Religious Event that Shaped the Era of Discovery.

- ↑ "Excursus on the words πίστιν ἑτέραν". Ccel.org. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Patricia Fortini. Laetentur Caeli: The Council of Florence and the Astronomical Fresco in the Old Sacristry. 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Погодин, Амвросий. Святой Марк Эфесский и Флорентийская уния. Jordanville: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1963.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stieber, Joachim W. Pope Eugenius IV, the Council of Basel and the Secular and Ecclesiastical Authorities in the Empire: The Conflict Over Supreme Authority and Power in the Church. 1978.

- ↑ Roman Catholicism, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015, O.Ed.

- 1 2 Brigham, Erin. Sustaining the Hope for Unity: Ecumenical Dialogue in a Postmodern World. 2012.

- ↑ Van der Essen, Léon. "The Council of Florence." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 24 Jul. 2014