Laconic phrase

| Look up laconic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

A laconic phrase or laconism is a concise or terse statement, especially a blunt and elliptical rejoinder.[1][2] It is named after Laconia, the region of Greece including the city of Sparta, whose ancient inhabitants had a reputation for verbal austerity and were famous for their blunt and often pithy remarks.

Uses

A laconic phrase may be used for efficiency (as in military jargon), for philosophical reasons (especially among thinkers who believe in minimalism, such as Stoics), or to better deflate a pompous individual (a famous example being at the Battle of Thermopylae).

One prominent example involves Philip II of Macedon, who after invading southern Greece and receiving the submission of other key city-states, sent a message to Sparta:

You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city.[3]

The Spartan ephors replied with a single word:

If.[4]

Subsequently, neither Philip nor his son Alexander the Great attempted to capture the city. Philip is also recorded as approaching Sparta on another (?) occasion and asking whether he should come as friend or foe; the reply was "Neither".[5]

In humour

The Spartans were especially famous for their dry, understated wit, which is now known as "laconic humor". This can be contrasted with the "Attic salt" or "Attic wit" – the refined, poignant, delicate humour of Sparta's chief rival Athens.

Various more recent groups also have a reputation for laconic humor: Australians (cf. Australian humor),[6][7][8] American cowboys,[9] New Englanders,[10] people from the North Country of England,[11] and Icelanders in the sagas.[12]

History

Spartans focused less than other ancient Greeks on the development of education, arts, and literature.[13] Some view this as having contributed to the characteristically blunt Laconian speech. However, Socrates, in Plato's dialogue Protagoras, appears to reject the idea that Spartans' economy with words was simply a consequence of poor literary education: "... they conceal their wisdom, and pretend to be blockheads, so that they may seem to be superior only because of their prowess in battle ... This is how you may know that I am speaking the truth and that the Spartans are the best educated in philosophy and speaking: if you talk to any ordinary Spartan, he seems to be stupid, but eventually, like an expert marksman, he shoots in some brief remark that proves you to be only a child".[14][note 1] Socrates was known to have admired Spartan laws,[15] as did many other Athenians,[16] but modern scholars have doubted the seriousness of his attribution of a secret love of philosophy to Spartans.[17] Still, two Spartans – Myson of Chenae and Chilon of Sparta – were traditionally counted among the Seven Sages of Greece to whom many famous sayings were ascribed.[note 2]

In general, however, Spartans were expected to be men of few words, to hold rhetoric in disdain, and to stick to the point. Loquacity was seen as a sign of frivolity, and unbecoming of sensible, down-to-earth Spartan peers. A Spartan youth was reportedly liable to have his thumb bitten as punishment for too verbose a response to a teacher's question.[20]

Examples

Spartan

- A witticism attributed to Lycurgus, the possibly legendary lawgiver of Sparta, was a response to a proposal to set up a democracy there: "Begin with your own family."[21]

- On another occasion, Lycurgus was reportedly asked the reason for the less-than-extravagant size of Sparta's sacrifices to the gods. He replied, "So that we may always have something to offer."[21]

- When he was consulted on how Spartans might best forestall invasion of their homeland, Lycurgus advised, "By remaining poor, and each man not desiring to possess more than his fellow."[21]

- When asked whether it would be prudent to build a defensive wall enclosing the city, Lycurgus answered, "A city is well-fortified which has a wall of men instead of brick."[21] (When another Spartan was later shown an Asian city with impressive fortifications, he remarked, "Fine quarters for women!"[22])

- Responding to a visitor who questioned why they put their fields in the hands of the helots rather than cultivate them themselves, Anaxandridas explained, "It was by not taking care of the fields, but of ourselves, that we acquired those fields."[23]

- King Demaratus, being annoyed by someone pestering him with a question concerning who the most exemplary Spartan was, answered "He that is least like you."[21]

- On her husband Leonidas's departure for battle with the Persians at Thermopylae, Gorgo, Queen of Sparta asked what she should do. He advised her: "Marry a good man and bear good children."[24][25]

- When Leonidas was in charge of guarding the narrow mountain pass at Thermopylae with just 7,000 allied Greeks in order to delay the invading Persian army, Xerxes offered to spare his men if they gave up their arms. Leonidas replied "Molon labe" (Greek: Μολών λαβέ), which translates to "Come and take them".[26] It was adopted as the motto of the Greek 1st Army Corps.

- When he was asked why he had come to fight such a huge host with so few men (300 Spartans), Leonidas answered, "If numbers are what matters, all Greece cannot match a small part of that army; but if courage is what counts, this number is sufficient." On being again asked a similar question, he replied, "I have plenty, since they are all to be slain."[27]

- Herodotus recounted another incident that preceded the Battle of Thermopylae. The Spartan Dienekes was told that the Persian archers were so numerous that when they shot their volleys, their arrows would blot out the sun. He responded, “So much the better, we'll fight in the shade”.[28] Today, Dienekes's phrase is the motto of the Greek 20th Armored Division.

- On the morning of the third and final day of the battle, Leonidas, knowing they were being surrounded, exhorted his men, "Eat well, for tonight we dine in Hades."[29]

- After the Greeks ended the threat of the second Persian invasion with their victory at Plataea, the Spartan commander Pausanias ordered that a sumptuous banquet the Persians had prepared be served to him and his officers. "The Persians must be greedy," he remarked, "when, having all this, yet they come to take our barleycakes."[30]

- When asked by a woman from Attica, "Why are you Spartan women the only ones who can rule men?", Gorgo replied, "Because we are also the only ones who give birth to men."[21][31]

- In an account from Herodotus, "When the banished Samians reached Sparta, they had audience of the magistrates, before whom they made a long speech, as was natural with persons greatly in want of aid." When it was over, the Spartans averred that they could no longer remember the first half of their speech, and thus "...could make nothing of the remainder. Afterwards the Samians had another audience, whereat they simply said, showing a bag which they had brought with them, 'The bag wants flour.' The Spartans answered that they did not need to have said 'the bag'; however, they resolved to give them aid."[32]

- Polycratidas was one of several Spartans sent on a diplomatic mission to some Persian generals, and being asked whether they came in a private or a public capacity, answered, "If we succeed, public; if not, private."[21]

- Following the disastrous sea battle of Cyzicus, the admiral Mindaros' first mate dispatched a succinct distress signal to Sparta. The message was intercepted by the Athenians and was recorded by Xenophon in his Hellenica: "Ships gone; Mindarus dead; the men starving; at our wits' end what to do".[33][34]

- A visitor to Sparta expressed surprise at the plain clothing of King Agesilaus II and other Spartans. Agesilaus remarked, "From this mode of life we reap a harvest of liberty."[35]

- When asked whether bravery or justice was a more important virtue, Agesilaus explained, "There is no use for bravery unless justice is present, and no need for bravery if all men are just."[36]

- After campaigning successfully for two years in Asia Minor, Agesilaus was poised to make major inroads into the Persian Empire when he was recalled to Greece to take part in the Corinthian War. He complied immediately, noting wryly, "I am being driven from Asia by ten thousand archers." (Persia had instigated the war by bribing a number of Greek city-states to adopt an anti-Spartan stance; the Persian gold coins, darics, were stamped with an image of an archer.)[37][note 3]

- After Agesilaus was wounded in one of his many battles against Thebes, Antalcidas remonstrated, "The Thebans pay you well for having taught them to fight, which they were neither willing nor able to do before."[21][note 4]

- Nearing death, Agesilaus was asked if he wanted a statue erected in his honor. He declined, saying; "If I have done anything noble, that is a sufficient memorial; if I have not, all the statues in the world will not preserve my memory."[38]

- When a Spartan argued in favor of waging war against Macedon, citing as support their previous successes against Persia, King Eudamidas retorted "You seem not to realize that your proposal is the same as fighting fifty wolves after defeating a thousand sheep."[39]

- When someone from Argos pointed out that Spartans were susceptible to being corrupted by foreign travel, Eudamidas replied, "But you, when you come to Sparta, do not become worse, but better."[40]

- Demetrius I of Macedon was offended when the Spartans sent his court a single envoy, and exclaimed angrily, "What! Have the Lacedaemonians sent no more than one ambassador?" The Spartan responded, "Aye, one ambassador to one king."[41]

- After being invited to dine at a public table, the sophist Hecataeus was criticized for failing to utter a single word during the entire meal. Archidamidas answered in his defense, "He who knows how to speak, knows also when."[21]

- Spartan mothers or wives gave a departing warrior his shield with the words: "With it or on it!" (Greek: Ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς! E tan e epi tas!), implying that he should return (victoriously) with his shield, or (his dead body) upon it, but by no means after saving himself by throwing away his heavy shield and fleeing.[42][43]

- The king of Pontus engaged a Spartan cook to prepare their famous black broth for him, but found it distasteful. The cook explained, "To relish this dish, one must first bathe in the Eurotas."[21]

- Upon being asked to listen to a person who could perfectly imitate a nightingale, a Spartan answered, "I have heard the nightingale itself."[44]

- When an Athenian accused Spartans of being ignorant, the Spartan Pleistoanax agreed: "What you say is true. We alone of all the Greeks have learned none of your evil ways."[21]

Other historical examples

- When Ben-Hadad I, king of Aram-Damascus, attacked Ahab, king of Israel, he sent a message: "May the gods deal with me, be it ever so severely, if enough dust remains in Samaria to give each of my men a handful." Ahab replied, "One who puts on his armor should not boast like one who takes it off."[45]

- A traveler from Sybaris, a city in southern Italy (which gave rise to the word sybarite) infamous in the ancient world for its luxury and gluttony, was invited to eat in a Spartan mess hall and tasted their black broth. Disgusted, he remarked, "No wonder Spartans are the bravest of men. Anyone in their right mind would rather die a thousand times than live like this."[46]

- When news of the death of Philip II reached Athens in 336 BC, the strategos Phocion banned all celebratory sacrifice, saying: "The army which defeated us at Chaeronea has lost just one man."[47]

- The heavy price of defeating the Romans in the Battle of Asculum (279 BC) prompted Pyrrhus to respond to an offer of congratulations with "If we win one more battle we will be doomed" ("One more such victory and the cause is lost"; in Greek: Ἂν ἔτι μίαν μάχην νικήσωμεν, ἀπολώλαμεν Án éti mían máchēn nikḗsōmen, apolṓlamen).[48]

- After the execution of the Catiline conspirators in 62 BC, Cicero announced "Vixerunt" – "They have lived." (This was a formulaic expression that avoided direct mention of death to forestall ill fortune.)[49]

- As Julius Caesar led his army across the Rubicon in northern Italy in 49 BC, signifying the beginning of Caesar's civil war, he is reported to have said in Greek, "The die is cast!", quoting Menander (Greek: "Anerriphtho kubos" (ἀνερρίφθω κύβος); Latin: "Alea iacta est").[50]

- Julius Caesar memorialized his swift victory over King Pharnaces II of Pontus in the Battle of Zela in 47 BC with a message to the Roman Senate consisting of the words "Veni, vidi, vici" ("I came, I saw, I conquered").[51]

- According to a legend recorded in the Primary Chronicle for year 6472, Sviatoslav I of Kiev (circa 962–972 AD) sent a message to the Vyatich rulers, consisting of a single phrase: "I come at you!" (Old East Slavic: "Иду на вы!" Idu na vi!).[52] The chronicler may have wished to contrast Sviatoslav's open declaration of war to stealthy tactics employed by many other early medieval conquerors. This phrase is used in modern Russian to denote an unequivocal declaration of one's intentions.

- In Chapter 76 of Njál's saga, Thorgrim and a few other grudge-bearing men were scouting around Gunnar Hámundarson's house. Gunnar woke up and stabbed Thorgrim through a gap with an atgeir (a type of spear). Thorgrim returned to his comrades, who asked if Gunnar was home. "Find that out for yourselves, but this I am sure of: that his atgeir is at home," he said, and fell down dead.[53]

- Charles VIII of France, who had entered Florence with his army in 1494, tried to impose exorbitant conditions with an ultimatum, accompanied by the words "otherwise we will sound our trumpets". To this Piero Capponi (at that time head of the Florentine Republic) answered "And we shall toll our bells", tearing up the ultimatum in the king's face. Charles, who did not relish the idea of house-to-house fighting, was forced to moderate his claim and concluded a more equitable treaty with the republic.

- During the Siege of Dongnae, upon being urged to surrender by general Konishi Yukinaga of the invading Japanese, prefect Song Sang-hyeon replied, "It is easier to die than to move aside" ("戰死易假道難").

- In 1809, during the second siege of Saragossa, the French demanded the city's surrender with the message "Peace and Surrender" ("Paz y capitulación"). General Palafox's reply was "War and knife" ("Guerra y cuchillo", often mistranslated as "War to the Knife").

- After defeating the British at the Battle of Lake Erie, American Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry sent a famously brief report of his victory, "We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop."

- Miloš Obrenović, leader of the second Serbian uprising, started the war with the words: "Here I am, here you are, war to the Turks."

- When asked to surrender the Imperial Guard during the Battle of Waterloo, General Cambronne is recorded as replying: La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas - "The Guard dies, it does not surrender". Some sources also record his response as the single word Merde (literally, shit, but it can also be roughly translated as "Go to Hell").[54] Merde is still euphemistically referred to in French as le mot de Cambronne- Cambronne's word.

- During the early 20th century struggle for central Arabia between the families of Al Rashid and Al Saud, Shaykh Abdul Aziz Al Rashid wrote to King Abdul Aziz Al Saud suggesting that rather than having their armies battle, the two leaders should settle the matter through single combat. The king replied with a one-line letter "From Abdul Aziz the living to Abdul Aziz the dead."

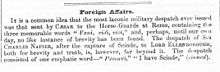

'Peccavi' - Punch Magazine, 18th May 1844

'Peccavi' - Punch Magazine, 18th May 1844 - In 1843, after annexing the then-Indian village Miani of Sindh against orders, legend has it that British General Sir Charles Napier sent home a one word telegram, "Peccavi", taking use of its Latin meaning "I have sinned" and the heterograph "I have Sindh.".[55] This pun appeared under the title 'Foreign Affairs' in Punch magazine on 18 May 1844. The true author of the pun was, however, Englishwoman Catherine Winkworth, who submitted it to Punch, which then printed it as a factual report.

- A similar (possibly apocryphal) story has Lord Dalhousie annexing Oudh and sending a one word telegram, 'Vovi', translated as 'I have vowed' ('Oudh' and 'vowed' are near-heterographs).[56]

- The shortest correspondence in history was between Victor Hugo and his publisher in 1862. Hugo was on vacation while Les Misérables was scheduled to be printed, and wondered how his book was being received. He telegraphed Hurst & Blackett the single-character message "?". Sales being brisk, the reply was a single "!".[57][58]

- Shortly after taking command of the French 9th Army during the early stages of the First World War, General Ferdinand Foch summarised his situation with the words "My center is giving way, my right is in retreat. Situation excellent. I attack." [59]

- On October 27, 1917, violinist Mischa Elman and pianist Leopold Godowsky listened in Carnegie Hall as sixteen-year-old violin prodigy Jascha Heifetz gave his first U.S. performance. At intermission, Elman wiped his brow and remarked "It's awfully hot in here", to which Godowsky retorted, “Not for pianists!”[60]

- On October 28, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian emperor Charles I of Austria tried to persuade the Slovene leader Anton Korošec not to join an independent Yugoslav State by offering to establish an autonomous United Slovenia within the Habsburg Monarchy. Korošec replied in German: Es ist zu spät, Majestät ("It is too late, your Majesty") and then, according to his own account, slowly left the room. The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was declared the next day with Korošec as its de facto leader.

- American President Calvin Coolidge had a reputation in private of being a man of few words and was nicknamed "Silent Cal". A possibly apocryphal story has it that a matron seated next to him at a dinner said to him, "I made a bet today that I could get more than two words out of you." His reply: "You lose."[61]

- Nobel Prize-winning British physicist Paul Dirac was notoriously taciturn.[note 5] During the question period after a lecture he gave at the University of Toronto, a member of the audience remarked that he hadn't understood part of a derivation. There followed a long and increasingly awkward silence. When the host finally prodded him to respond, Dirac simply said, "That was a statement, not a question."[62]

- Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli (also a Nobel laureate), known as the conscience of the physics world for his colorful objections to incorrect or sloppy thinking, was shown a young physicist's paper and lamented, "[This is so bad,] it is not even wrong."[63]

- During World War II when Greek dictator Ioannis Metaxas refused Axis demands for occupation of Greek territory under threat of war, he was supposed to have replied with a single word—Όχι (Ohi)—"No." The anniversary of his refusal is today celebrated as Ohi Day. Since then it has been reported that his actual response was "Alors, c'est la guerre" ("It's war then", in French).

- A Lockheed Hudson of 82 Naval Patrol squadron, operating from Argentia in Newfoundland, sighted and attacked a surfaced U-boat on 28 January 1942. After the U-boat submerged undamaged, the mistakenly triumphant pilot, Donald Francis Mason, signaled “Sighted sub sank same”.[64]

- After the sinking of light carrier Shōhō in the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea, LCDR Robert E. Dixon radioed "Scratch one flattop” to U.S.S. Lexington, whose commanding officer credited the pilot with coining the standard USN slang.[65]

- During the Battle of Arnhem, Walter Harzer, commanding the near 16,000 strong 9th SS Panzer Division, sent his batman to the massively outnumbered 740 British paratroops holding the north end of the bridge to "discuss terms of surrender". The paras commander, Johnnie Frost replied "Sorry, we don't have the facility to take you all prisoner."

- Upon hearing that the 101st Airborne division was surrounded in Bastogne by 26 German divisions during the December 1944 Battle of the Bulge, Lt Col Creighton Abrams said: "They've got us surrounded again, the poor bastards."[66]

- During the Battle of Bastogne, the Germans sent the Americans a party of envoys with an ultimatum: surrender or face "certain annihilation". The German officer in charge was perplexed when General Anthony McAuliffe replied with one word: "Nuts!"[note 6]

- During the Berlin Blockade, a Soviet radio tower was causing problems at the newly constructed Tegel Airfield, so French general Jean Ganeval had it demolished. When a furious Soviet commander demanded to know how he could have done it, he responded, "With dynamite, my dear colleague."

- In the Korean War, after U.N. forces under American command were attacked by Chinese forces in the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, U.S. commander Chesty Puller remarked, "We've been looking for the enemy for some time now. We've finally found him. We're surrounded. That simplifies things."[68] He also reportedly said, "Great. Now we can shoot at those bastards from every direction."

See also

Notes

- ↑ An alternative translation by A. Beresford and R. Allen is as follows: "...they claim not to have any interest in [philosophy] and put on this big show of being morons...because...they want people to think that their superiority rests on fighting battles and being manly... You can tell that what I say is true, and that Spartans are the best educated in philosophy and argument, by this: if one associates with the most inferior Spartan, one at first finds him somewhat inferior in speech; but then at some chance point in the discussion he throws in a remark worthy of noticing, brief and terse, like a skilled marksman, so that the person he's talking to appears no better than a child."

- ↑ Examples include "We should not investigate facts by the light of arguments, but arguments by the light of facts" for Myson,[18] and "Do not let one's tongue outrun one's sense" for Chilon.[19]

- ↑ Before sailing across the Aegean to Asia Minor, Agesilaus had planned to offer sacrifice at Aulis, but was prevented from doing so by the intervention of Thebes, something he never forgave. His withdrawal from Asia led to all Asiatic Greeks falling under Persian dominion. The Persian Empire was afforded a 60-year respite from Hellenic invasion, until it was finally overwhelmed by Alexander.

- ↑ By repeatedly campaigning against Thebes, Agesilaus had violated one of the maxims (rhetras) of Lycurgus, namely that Sparta should not make war frequently with the same opponents, lest by doing so it should school them in military arts. This transgression led to the downfall of Sparta after its defeat by Thebes in the Battle of Leuctra, and ultimately to the downfall of Greece, after Philip II of Macedon obtained military training while a hostage at Thebes and then defeated Thebes and its Greek coalition in the Battle of Chaeronea.

- ↑ This began early. When Dirac was a child, his authoritarian father, a teacher of French, enforced a rule that Dirac speak to him only in French, as a device to encourage him to learn the language. But since young Dirac had difficulty expressing himself in French, the result was he spoke very little.

- ↑ When the German officer had to ask, "Is the reply negative or affirmative?", it was explained to him as being equivalent to "Go to hell."[67]

References

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Synonyms, 1984, s.v. 'concise' p. 172

- ↑ Henry Percy Smith, Synonyms Discriminated (1904) p. 541

- ↑ The Animal Spirit Doctrine and the Origins of Neurophysiology, C.U.M. Smith, et al., Oxford University Press, 2012

- ↑ Plutarch, "De garrulitate, 17" 1 2 or 3

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 233e 1 2

- ↑ Willbanks, R. (1991). Australian Voices: Writers and Their Work. University of Texas Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-292-78558-8. OCLC 23220737.

- ↑ Bell, S.; Bell, K.; Byrne, R. (2013). "Australian Humour: What Makes Aussies Laugh?". Australian Tales. Australian-Information-Stories.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-22. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- ↑ Jones, D. (1993). "Edgy laughter: Women and Australian humour". Australian Literary Studies. 16 (2): 161–167. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- ↑ Collier, P.; Horowitz, D. (1995). Roosevelts: An American Saga. Simon & Schuster. p. 66. ISBN 9780684801407. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- ↑ Islands Magazine. p. 108. ISSN 0745-7847. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- ↑ Urdang, L. (1988). Names and Nicknames of Places and Things. Penguin Group USA. ISBN 9780452009073. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- ↑ Peter Hallberg, The Icelandic Saga, p. 115

- ↑ Plato, Hippias Major 285b-d.

- ↑ Protagoras 342b, d-e, from the translation given at the end of the section on Lycurgus in e-classics.com.

- ↑ Plato, Crito 52e.

- ↑ Plato, Republic 544c.

- ↑ p. 255, A.E. Taylor, Plato: The Man and His Work, Meridian Books, 6th ed., 1949; p. 83, C.C.W. Taylor, Plato: Protagoras, Oxford University Press, 2002; p. 151, A. Beresford, Plato: Protagoras and Meno, Penguin Books 2005.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertius. Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Translated by Robert Drew Hicks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Volume 1. 1982. Page 113

- ↑ Diogenes Laertius, i. 68-73

- ↑ Paul Cartledge (2003). Spartan Reflections. University of California Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-520-23124-5. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Plutarch: Life of Lycurgus 1 2 3

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 230c

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica (Sayings of Spartans), 217a. This work may or may not be by Plutarch himself, but is included among the Moralia, a collection of works attributed to him but outside the collection of his most famous works, the Parallel Lives.

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 225a.

- ↑ Plutarch, Lacaenarum Apophthegmata (Sayings of Spartan Women), 240e. This work may or may not be by Plutarch himself, but is included among the Moralia, a collection of works attributed to him but outside the collection of his most famous works, the Parallel Lives.

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 225c.

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 225c.8-9.

- ↑ Herodotus The Histories, Book Seven, section 226.

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 225d

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 230f

- ↑ Plutarch, Lacaenarum Apophthegmata, 240e

- ↑ Herodotus The Histories, Book 3, section 46.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenica 1.1.23

- ↑ Brownson, C. L. (1918). "Xenophon in Seven Volumes". Hellenica. Heinemann. Archived from the original on 2014-09-20. Retrieved 2014-09-20.

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 210a

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 213c

- ↑ Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Agesilaus", 15.6.123

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 215a

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 220f

- ↑ Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica, 221a

- ↑ Plutarch: Life of Demetrius

- ↑ Plutarch, Lacaenarum Apophthegmata, 241f.16.

- ↑ "Sparta: Famous quotes about Spartan life". The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization. PBS. November 1999. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- ↑ Attributed to no one in particular in Plutarch's Life of Lycurgus, to Agesilaus II in Plutarch's Life of Agesilaus, and to Pleistarchus in the Apophthegmata Laconica of the Moralia.

- ↑ I Kings 20:10-11

- ↑ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae Book IV, 138d; Book XII, 518e; trans. quoted in Dalby, A. Siren Feasts: A History of Food and Gastronomy in Greece. London: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-415-15657-2, p.126.

- ↑ Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Phocion", 16.6.

- ↑ Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Pyrrhus", 21.9.

- ↑ Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Cicero", 22.4.

- ↑ Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Caesar", 32.8.

- ↑ Julius Caesar, The Gallic Wars.

- ↑ The Russian Primary Chronicle

- ↑ "Brennu-Njáls saga (see section 76)". Omacl.org. 2004-12-01. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Boller, Jr., Paul F.; George, John (1989). They Never Said It: A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes, and Misleading Attributions. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505541-1.

- ↑ Eugene Ehrlich, Nil Desperandum: A Dictionary of Latin Tags and Useful Phrases [Original title: Amo, Amas, Amat and More], BCA 1992 [1985], p. 175.

- ↑ "Opinion". blogs.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- ↑ William S. Walsh (1892). Handy-Book of Literary Curiosities. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co. p. 600.

- ↑ Writing, Not (2007-01-18). "The Shortest Complete Sentence in the English Language". Humanities 360. Helium Publishing. Archived from the original on 2014-06-13. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

- ↑ Neiberg, Michael (2003). "Foch: Supreme Allied Commander in the Great War". Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-672-X.

- ↑ Nicholas, Jeremy. "Wit and Wisdom". www.godowsky.com. Archived from the original on 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ↑ Coolidge, Calvin (2001). Hannaford, Peter, ed. The Quotable Calvin Coolidge: Sensible Words for a New Century. Bennington, Vermont: Images From the Past. p. 169. ISBN 1-884592-33-3.

- ↑ Dirac, Gisela. "Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (1902-1984)". DIRAC Family Research. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ↑ Peierls R (1960). "Wolfgang Ernst Pauli, 1900-1958". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. Royal Society (Great Britain). 5: 174–192. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1960.0014.

- ↑ Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler’s U-Boat War Vol I. ISBN 0-304-35260-8.

- ↑ Hearn, Chester (2005). Carriers in Combat: The Air War At Sea. Stackpole Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8117-3398-4.

- ↑ "Creighton Abrams Biography". BiographyBase.com. Retrieved 2016-10-19.

- ↑ S.L. A. Marshall, Bastogne: The First Eight Days, Chapter 14, detailing and sourcing the incident.

- ↑ Russ, Martin (1999). Breakout – The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, Korea, 1950. Penguin Books. p. 230. ISBN 0-14-029259-4.