Laban Movement Analysis

Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), sometimes Laban/Bartenieff Movement Analysis, is a method and language for describing, visualizing, interpreting and documenting human movement. It is based on the original work of Rudolf Laban, which was developed and extended by Lisa Ullmann, Irmgard Bartenieff, Warren Lamb and others. LMA draws from multiple fields including anatomy, kinesiology and psychology. It is used by dancers, actors,[1] musicians and athletes; by health professionals such as physical and occupational therapists and psychotherapists;[2] and in anthropology, business consulting and leadership development.[3]

Labanotation (or Kinetography Laban), a notation system for recording and analyzing movement, is used in LMA, but Labanotation is a separate system.

Categories of Movement

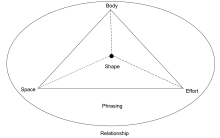

Laban Movement Analysis is generally divided into four categories:[4]

- Body (Bartenieff Fundamentals, total-body connectivity)

- Effort (Energetic dynamics)

- Shape

- Space (Choreutics, Space Harmony)

Other categories, that are occasionally mentioned in some literature, are Relationship and Phrasing. These are less well defined. Relationship is the interaction between people, body parts or a person and an object. Phrasing is defined as being the personal expression of a movement.

These categories are in turn occasionally divided into Kinematic and Non-Kinematic categories to distinguish which categories relate to changes to body relations over time and space.[5][6]

Body

The body category describes structural and physical characteristics of the human body while moving. This category is responsible for describing which body parts are moving, which parts are connected, which parts are influenced by others, and general statements about body organization.

Several subcategories of Body are:

- Initiation of movement starting from specific bodies;

- Connection of different bodies to each other;

- Sequencing of movement between parts of the body; and

- Patterns of body organization and connectivity, called "Patterns of Total Body Square Connectivity", "Developmental Hyper Movement Patterns", or "Neuromuscular Shape-Shifting Patterns".

Effort

Effort, or what Laban sometimes described as dynamics, is a system for understanding the more subtle characteristics about movement with respect to inner intention. The difference between punching someone in anger and reaching for a glass is slight in terms of body organization – both rely on extension of the arm. The attention to the strength of the movement, the control of the movement and the timing of the movement are very different.

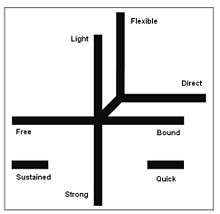

Effort has four subcategories (Effort factors), each of which has two opposite polarities (Effort elements).[7]

| Effort Factor | Effort element (Fighting polarity) | Effort element (Indulging polarity) |

|---|---|---|

| Space | Direct | Indirect (Flexible) |

| Weight | Strong | Light |

| Time | Sudden (quick) | Sustained |

| Flow | Bound | Free |

Laban named the combination of the first three categories (Space, Weight, and Time) the Effort Actions, or Action Drive. The eight combinations are descriptively named Float, Punch (Thrust), Glide, Slash, Dab, Wring, Flick, and Press. The Action Efforts have been used extensively in some acting schools, including ALRA, Manchester School of Theatre, LIPA and London College of Music to train in the ability to change quickly between physical manifestations of emotion.

Flow, on the other hand, is responsible for the continuousness or ongoingness of motions. Without any Flow Effort, movement must be contained in a single initiation and action, which is why there are specific names for the Flow-less Action configurations of Effort. In general it is very difficult to remove Flow from much movement, and so a full analysis of Effort will typically need to go beyond the Effort Actions.

Shape

While the Body category primarily develops connections within the body and the body/space intent, the way the body changes shape during movement is further experienced and analyzed through the Shape category. It is important to remember that all categories are related, and Shape is often an integrating factor for combining the categories into meaningful movement.

There are several subcategories in Shape:

- "Shape Forms" describe static shapes that the body takes, such as Wall-like, Ball-like, and Pin-like.

- "Modes of Shape Change" describe the way the body is interacting with and the relationship the body has to the environment. There are three Modes of Shape Change:

- Shape Flow: Representing a relationship of the body to itself. Essentially a stream of consciousness expressed through movement, this could be amoebic movement or could be mundane habitual actions, like shrugging, shivering, rubbing an injured shoulder, etc.

- Directional: Representing a relationship where the body is directed toward some part of the environment. It is divided further into Spoke-like (punching, pointing, etc.) and Arc-like (swinging a tennis racket, painting a fence)

- Carving: Representing a relationship where the body is actively and three dimensionally interacting with the volume of the environment. Examples include kneading bread dough, wringing out a towel, avoiding laser-beams or miming the shape of an imaginary object. In some cases, and historically, this is referred to as Shaping, though many practitioners feel that all three Modes of Shape Change are "shaping" in some way, and that the term is thus ambiguous and overloaded.

- "Shape Qualities" describe the way the body is changing (in an active way) toward some point in space. In the simplest form, this describes whether the body is currently Opening (growing larger with more extension) or Closing (growing smaller with more flexion). There are more specific terms – Rising, Sinking, Spreading, Enclosing, Advancing, and Retreating, which refer to specific dimensions of spatial orientations.

- "Shape Flow Support" describes the way the torso (primarily) can change in shape to support movements in the rest of the body. It is often referred to as something which is present or absent, though there are more refined descriptors.

The majority of the Shape category was not developed during Laban's life, but added later by his followers. Warren Lamb was instrumental in creating a significant amount of the theoretical structure for understanding this category.

Space

One of Laban's primary contributions to Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) are his theories of Space. This category involves motion in connection with the environment, and with spatial patterns, pathways, and lines of spatial tension. Laban described a complex system of geometry based on crystalline forms, Platonic solids, and the structure of the human body. He felt that there were ways of organizing and moving in space that were specifically harmonious, in the same sense as music can be harmonious. Some combinations and organizations were more theoretically and aesthetically pleasing. As with music, Space Harmony sometimes takes the form of set 'scales' of movement within geometric forms. These scales can be practiced in order to refine the range of movement and reveal individual movement preferences. The abstract and theoretical depth of this part of the system is often considered to be much greater than the rest of the system. In practical terms, there is much of the Space category that does not specifically contribute to the ideas of Space Harmony.

This category also describes and notates choices which refer specifically to space, paying attention to:

- Kinesphere: the area that the body is moving within and how the mover is paying attention to it.

- Spatial Intention: the directions or points in space that the mover is identifying or using.

- Geometrical observations of where the movement is being done, in terms of emphasis of directions, places in space, planar movement, etc.

The Space category is currently under continuing development, more so since exploration of non-Euclidean geometry and physics has evolved.

Use in Human-Computer Interaction

LMA is used in Human-Computer Interaction as a means of extracting useful features from a human's movement to be understood by a computer,[8] as well as generating realistic movement animation for virtual agents [9] and robots.[10]

Formal Study

Laban Movement Analysis practitioners and educators who studied at LIMS, an accredited institutional member of the National Association of Schools of Dance (NASD), are known as "Certified Movement Analysts" (CMAs). Other courses offer LMA studies, including Integrated Movement Studies, which qualifies "Certified Laban/Bartenieff Movement Analysts" (CLMAs).

See also

- Laban Movement Studies

- Benesh Movement Notation

- Choreography

- Dance notation

- Dance Notation Bureau

- Lea Anderson

- Motif description

Notes and references

- ↑ Newlove, J. (1993) Laban for Actors and Dancers: Putting Laban's Movement Theory into Practice, Nick Hern Books, London. ISBN 978-1-85459-160-9

- ↑ Bartenieff, Irmgard, and Dori Lewis. Body movement: Coping with the environment. Psychology Press, 1980.

- ↑ Lamb, Warren, and Turner, D. (1969). Management Behaviour. New York: International Universities Press.

- ↑ "Theory". www.laban-eurolab.org. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ↑ Foroud, Afra, and Ian Q. Whishaw. "Changes in the kinematic structure and non-kinematic features of movements during skilled reaching after stroke: A laban movement analysis in two case studies." Journal of neuroscience methods 158, no. 1 (2006): 137-149.

- ↑ Rett, Jörg, and Jorge Dias. "Human robot interaction based on bayesian analysis of human movements." In Portuguese Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pp. 530-541. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007.

- ↑ Laban, Rudolf, and Lawrence, F. C. Effort. (1947). London: MacDonald and Evans.

- ↑ Roudposhti, Kamrad Khoshhal, Luís Santos, Hadi Aliakbarpour, and Jorge Dias. "Parameterizing interpersonal behaviour with laban movement analysis—a bayesian approach." In Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2012 IEEE Computer Society Conference on, pp. 7-13. IEEE, 2012.

- ↑ Chi, Diane, Monica Costa, Liwei Zhao, and Norman Badler. "The EMOTE model for effort and shape." In Proceedings of the 27th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, pp. 173-182. ACM Press/Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 2000.

- ↑ Nakata, Toru, Tomomasa Sato, Taketoshi Mori, and Hiroshi Mizoguchi. "Expression of emotion and intention by robot body movement." In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Autonomous Systems. 1998.

Further reading

- Bartenieff, Irmgard, and Dori Lewis (1980). Body Movement; Coping with the Environment. New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Hackney, Peggy (1998) Making Connections: Total Body Integration through Bartenieff Fundamentals, Routledge Publishers, New York. ISBN 90-5699-591-X

- Laban, Rudolf (1926). Choreographie. (German) Jena: Eugen Diederichs. (Unpublished English edition translated by Evamaria Zierach and Jeffrey Scott Longstaff [1993]

- Laban, R. (1963). Modern Educational Dance. 2nd edition revised by L. Ullmann. London: MacDonald and Evans. (First published 1948).

- Laban, R. (1966). Choreutics. Annotated and edited by L. Ullmann. London: MacDonald and Evans. (Published in U.S.A. as The Language of Movement; A Guide Book to Choreutics. Boston: Plays.)

- Laban, R. (1975). Laban’s Principles of Dance and Movement Notation. 2nd edition edited and annotated by R. Lange. London: MacDonald and Evans. (First published 1956.)

- Laban, R. (1980). The Mastery of Movement. 4th edition revised and enlarged by L. Ullmann. London: MacDonald and Evans. (First published as The Mastery of Movement on the Stage, 1950.)

- Laban, R. (1984). A Vision of Dynamic Space. Compiled by L. Ullmann. London: The Falmer Press.

- Laban, R., and Lawrence, F. C. (1947) Effort. London: MacDonald and Evans. (4th reprint 1967).

- Lamb, Warren (1965). Posture and Gesture; An Introduction to the Study of Physical Behaviour. London: Gerald Duckworth.

- Lamb, Warren, and Watson, E. (1979). Body Code; The Meaning in Movement. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Moore, Carol Lynne (1982). Executives in Action: A Guide to Balanced Decision–making in Management. Estover, Plymouth: MacDonald & Evans. (First published as Action Profiling, 1978.)

- Moore, Carol Lynne and Kaoru Yamamoto (1988). Beyond Words. New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Newlove, J. & Dalby, J. (2005) Laban for All, Nick Hern Books, London. ISBN 978-1-85459-725-0

- Ullmann, Lisa (1955). Space Harmony VI. Laban Art of Movement Guild Magazine. 15 (Oct.): 29-34.

- Ullmann, Lisa (1966). Rudiments of space-movement. In Choreutics, by R. Laban, annotated and edited by L. Ullmann (pp. 138–210). London: MacDonald and Evans.

- Ullmann, Lisa (1971). Some Preparatory Stages for the Study of Space Harmony in Art of Movement. Surrey: Laban Art of Movement Guild.

- Ullmann, Lisa (1975). Some hints for the student of movement. In Modern Educational Dance, by R. Laban; 3rd edition revised and edited by L. Ullmann (pp. 108–134). London: MacDonald & Evans.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labanotation. |

- Laban/Bartenieff & Somatic Studies Canada (LSSC)

- Laban/Bartenieff & Somatic Studies International (LSSI)

- Laban Analyses.org Laban analysis and Labanotation searchable database

- What is LMA? (Glossary)

- NYU Movement Lab: Intro to LMA