La Tène culture

.jpg)

| Geographical range | much of Western and Central Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Iron Age Europe |

| Dates | circa 500 BCE. — circa 1 BCE |

| Type site | La Tène, Neuchâtel |

| Preceded by | Hallstatt culture "D" |

| Followed by | Roman Empire |

.jpg)

The La Tène culture (/ləˈtɛn/; French pronunciation: [la tɛn]) was a European Iron Age culture named after the archaeological site of La Tène on the north side of Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland, where thousands of objects had been deposited in the lake, as was discovered after the water level dropped in 1857.[1]

La Tène is the type site and the term archaeologists use for the later period of the culture and art of the ancient Celts, a term that is firmly entrenched in the popular understanding, but presents numerous problems for historians and archaeologists.[2] The culture became very widespread, and presents a wide variety of local differences. It is often distinguished from earlier and neighbouring cultures mainly by the La Tène style of Celtic art, characterized by curving "swirly" decoration, especially of metalwork.[3]

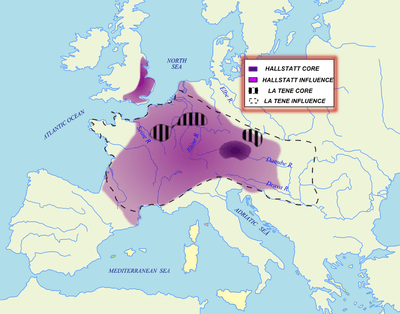

La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 500 BCE to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BCE) in Belgium, eastern France, Switzerland, Austria, Southern Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia and parts of Hungary, Ukraine and Romania. The Celtiberians of western Iberia shared many aspects of the culture, though not generally the artistic style. To the north extended the contemporary Pre-Roman Iron Age of Northern Europe, including the Jastorf culture of Northern Germany.

La Tène culture developed out of the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any definite cultural break, under the impetus of considerable Mediterranean influence from the Greeks in pre-Roman Gaul, the Etruscans,[4] and Golasecca culture.[5] Barry Cunliffe notes localization of La Tène culture during the 5th century when there arose "two zones of power and innovation: a Marne – Moselle zone in the west with trading links to the Po Valley via the central Alpine passes and the Golasecca culture, and a Bohemian zone in the east with separate links to the Adriatic via the eastern Alpine routes and the Venetic culture".[6] A shift of settlement centres took place in the 4th century.

La Tène cultural material appeared over a large area, including parts of Ireland and Great Britain, northern Spain, northern-central Italy,[7] Burgundy, and Austria. Elaborate burials also reveal a wide network of trade. In Vix, France, an elite woman of the 6th century BCE was buried with a very large bronze "wine-mixer" made in Greece. Exports from La Tène cultural areas to the Mediterranean cultures were based on salt, tin, copper, amber, wool, leather, furs and gold. Although the La Tène culture had no writing of its own (rare examples of it using Greek inscriptions exist, and late Celtic coinage often uses Latin) there are several accounts of the culture and aspects of its history from classical authors, most very hostile and tending to stereotype.

History

The preceding "Halstatt D" culture, of about 650-475, was also very widespread across Europe, and the transition over this area was gradual, and is mainly detected through La Tène style elite artefacts, which first appear in the western end of the old Hallstatt region.

The establishment of a Greek colony, soon very successful, at Massalia (modern Marseilles) on the Mediterranean coast of France led to great trade with the Hallstatt areas up the Rhone and Saone river systems, and early La Tène elite burials like the Vix Grave in Burgundy contain imported luxury goods along with artifacts produced locally. Most areas were probably controlled by tribal chiefs living in hilltop forts, while the bulk of the population lived in small villages or farmsteads in the countryside.[8]

By 500 the Etruscans expanded to border Celts in north Italy, and trade across the Alps began to overhaul trade with the Greeks, and the Rhone route declined. Booming areas included the middle Rhine, with large iron ore deposits, the Marne and Champagne regions, and also Bohemia, although here trade with the Mediterranean area was much less important. Trading connections and wealth no doubt played a part in the origin of the La Tène style, though how large a part remains much discussed; specific Mediterranean-derived motifs are evident, but the new style does not depend on them.[9]

By about 400 the evidences for Mediterranean trade become few; this may have been because the expanding Celtic populations began to migrate south and west, coming into violent conflict with the established populations, including the Etruscans and Romans. The settled life in much of the La Tène homelands also seems to have become much more unstable and prone to wars. In about 387 the Celts under Brennus defeated the Romans and then sacked Rome, establishing themselves as the most prominent threats to the Roman homeland, a status they would retain through a series of Roman-Gallic wars until Julius Caesar's final conquest of Gaul in 58-50 BCE. The Romans prevented the Celts from reaching very far south of Rome, but on the other side of the Adriatic Sea groups passed through the Balkans to reach Greece, where Delphi was attacked in 279, and Asia, where Galatia was established as a Celtic area of Anatolia. By this time the La Tène style was spreading to the British Isles, though apparently without any significant movements in population.[10]

After about 275 the relentless Roman expansion into the area occupied by La Tène culture began; it would never be complete, but lasted until the 1st century CE in Britain, leaving only the approximate areas of the modern Celtic nations (excluding Brittany) unoccupied. The Romans never attempted to invade Ireland and eventually decided that expansion into north Scotland was not worth the trouble, retreating from the line of the Antonine Wall to Hadrian's Wall in 162 CE.[11]

La Tène homeland

Though there is no agreement on the precise region in which La Tène culture first developed, there is a broad consensus that the center of the culture lay on the northwest edges of Hallstatt culture, north of the Alps, within the region between in the West the valleys of the Marne and Moselle, and the part of the Rhineland nearby. In the east the western end of the old Hallstatt core area in modern Bavaria, Austria and Switzerland formed a somewhat separate "eastern style Province" in the early La Tène, joining with the western area in Alsace.[12]

In 1994 a prototypical ensemble of elite grave sites of the early 5th century BCE was excavated at Glauberg in Hesse, northeast of Frankfurt-am-Main, in a region that had formerly been considered peripheral to the La Tène sphere.[13] The site at La Tène itself was therefore near the southern edge of the original "core" area (as is also the case for the Hallstatt site for its core).

From their homeland, La Tène culture expanded in the 4th century to more of modern France, Germany, and Central Europe, and beyond to Hispania, northern and central Italy, the Balkans, and even as far as Asia Minor, in the course of several major migrations. La Tène style artefacts start to appear in Britain around the same time,[14] and Ireland rather later. The style of "Insular La Tène" art is somewhat different and the artefacts are initially found in some parts of the islands but not others. Migratory movements seem at best only partly responsible for the diffusion of La Tène culture there, and perhaps other parts of Europe.[15]

Periodization

Extensive contacts through trade are recognized in foreign objects deposited in elite burials; stylistic influences on La Tène material culture can be recognized in Etruscan, Italic, Greek, Dacian and Scythian sources. Dateable Greek pottery and analysis employing scientific techniques such as dendrochronology and thermoluminescence help provide date ranges for an absolute chronology at some La Tène sites.

As with many archaeological periods, La Tène history was originally divided into "early" (6th century BCE), "middle" (c. 450–100 BCE), and "late" (1st century BCE) stages, with the Roman occupation greatly disrupting the culture, although many elements remain in Gallo-Roman and Romano-British culture.[16] A broad cultural unity was not paralleled by overarching social-political unifying structures, and the extent to which the material culture can be linguistically linked is debated. The art history of La Tène culture has various schemes of periodization.[17]

Ethnology

Our knowledge of this cultural area derives from three sources: from archaeological evidence, from Greek and Latin literary evidence, and more controversially, from ethnographical evidence suggesting some La Tène artistic and cultural survivals in traditionally Celtic regions of far western Europe. Some of the societies that are archaeologically identified with La Tène material culture were identified by Greek and Roman authors from the 5th century onwards as Keltoi ("Celts") and Galli ("Gauls"). Herodotus (iv.49) correctly placed Keltoi at the source of the Ister/Danube, in the heartland of La Tène material culture: "The Ister flows right across Europe, rising in the country of the Celts", whom however, apparently misunderstanding his source,[18] he places "farthest to the west of any people of Europe"[19]

Whether the usage of classical sources means that the whole of La Tène culture can be attributed to a unified Celtic people is difficult to assess; archaeologists have repeatedly concluded that language, material culture, and political affiliation do not necessarily run parallel. Frey notes (Frey 2004) that in the 5th century, "burial customs in the Celtic world were not uniform; rather, localised groups had their own beliefs, which, in consequence, also gave rise to distinct artistic expressions".

The spread of the Celtic languages before and during the period is also uncertain. In the 19th century it used to be thought that these only reached Ireland and Britain in the 1st millennium BCE, but it is now thought likely that they were dominant before the arrival of cultural styles associated with Celts, perhaps long before.[20]

Material culture

La Tène metalwork in bronze, iron and gold, developing technologically out of Hallstatt culture, is stylistically characterized by inscribed and inlaid intricate spirals and interlace, on fine bronze vessels, helmets and shields, horse trappings and elite jewelry, especially the neck rings called torcs and elaborate clasps called fibulae. It is characterized by elegant, stylized curvilinear animal and vegetal forms, allied with the Hallstatt traditions of geometric patterning.

The Early Style of La Tène art and culture mainly featured static, geometric decoration, while the transition to the Developed Style constituted a shift to movement-based forms, such as triskeles. Some subsets within the Developed Style contain more specific design trends, such as the recurrent serpentine scroll of the Waldalgesheim Style [21]

Initially La Tène people lived in open settlements that were dominated by the chieftains’ hill forts. The development of towns—oppida—appears in mid-La Tène culture. La Tène dwellings were carpenter-built rather than of masonry. La Tène peoples also dug ritual shafts, in which votive offerings and even human sacrifices were cast. Severed heads appear to have held great power and were often represented in carvings. Burial sites included weapons, carts, and both elite and household goods, evoking a strong continuity with an afterlife.[22]

Site of La Tène

La Tène is a village on the northern shore of Lake Neuchâtel, Switzerland, where the small river Thielle, connecting to another lake, enters the Lake Neuchâtel. It is an archaeological site and the eponymous type site for the late Iron Age La Tène culture. In 1857, prolonged drought lowered the waters of the lake by about 2 m. On the northernmost tip of the lake, between the river and a point south of the village of Marin-Epagnier, Hansli Kopp, looking for antiquities for Colonel Frédéric Schwab, discovered several rows of wooden piles that still reached up about 50 cm into the water. From among these, Kopp collected about forty iron swords.

The Swiss archaeologist Ferdinand Keller published his findings in 1868 in his influential first report on the Swiss pile dwellings (Pfahlbaubericht). In 1863 he interpreted the remains as a Celtic village built on piles. Eduard Desor, a geologist from Neuchâtel, started excavations on the lakeshore soon afterwards. He interpreted the site as an armory, erected on platforms on piles over the lake and later destroyed by enemy action. Another interpretation accounting for the presence of cast iron swords that had not been sharpened, was of a site for ritual depositions.

With the first systematic lowering of the Swiss lakes from 1868 to 1883, the site fell completely dry. In 1880, Emile Vouga, a teacher from Marin-Epagnier, uncovered the wooden remains of two bridges (designated "Pont Desor" and "Pont Vouga") originally over 100 m long, that crossed the little Thielle River (today a nature reserve) and the remains of five houses on the shore. After Vouga had finished, F. Borel, curator of the Marin museum, began to excavate as well. In 1885 the canton asked the Société d'Histoire of Neuchâtel to continue the excavations, the results of which were published by Vouga in the same year.

All in all, over 2500 objects, mainly made from metal, have been excavated in La Tène. Weapons predominate, there being 166 swords (most without traces of wear), 270 lanceheads, and 22 shield bosses, along with 385 brooches, tools, and parts of chariots. Numerous human and animal bones were found as well. The site was used from the 3rd century, with a peak of activity around 200 BCE and abandonment by about 60 BCE.[23] Interpretations of the site vary. Some scholars believe the bridge was destroyed by high water, while others see it as a place of sacrifice after a successful battle (there are almost no female ornaments).

An exhibition marking the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the La Tène site opened in 2007 at the Musée Schwab in Bienne, Switzerland, moving to move to Zürich in 2008 and Mont Beuvray in Burgundy in 2009.

Sites

Some sites are:

|

|

Artifacts

See Category:Celtic art.

Some outstanding La Tène artifacts are:

- Vix Grave of a very wealthy woman in Burgundy) buried with an 1100-litre (290 gallon) bronze krater, the largest ever found.

- Mšecké Žehrovice Head, a stone head from the modern Czech Republic

- A life-sized sculpture of a warrior that stood above the Glauberg burials

- Chariot burial found at La Gorge Meillet (St-Germain-en-Laye: Musée des Antiquités Nationales)

- Basse Yutz Flagons 5th century

- Agris Helmet, with gold covering, c. 350

- Waldalgesheim chariot burial, Bad Kreuznach, Germany, late 4th century BCE, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn; the "Waldalgesheim phase/style" of the art takes its name from the jewellery found here.

- A gold-and-bronze model of an oak tree (3rd century BCE) found at the Oppidum of Manching.

- Sculptures from Roquepertuse, a sanctuary in the south of France

- The silver Gundestrup cauldron (2nd or 1st century BCE), found ritually broken in a peat bog near Gundestrup, Denmark, but probably made near the Black Sea, perhaps in Thrace. (National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen)

- Battersea Shield (350–50 BCE), found in the Thames, made of bronze with red enamel. (British Museum, London)

- Waterloo Helmet, 150-50 BCE, found in London in the Thames

- "Witham Shield" (4th century BCE). (British Museum, London) [24]

- Torrs Pony-cap and Horns, from Scotland

- Cordoba Treasure

- Turoe stone in Galway, Ireland

- Great Torc from Snettisham, 100-75 BCE, gold, the most elaborate of the British style of torcs

- Meyrick Helmet, post-conquest Roman helmet shape, with La Tène decoration

- Noric steel

Notes

- ↑ Or just "La Tene" in English. More rarely also spelt "Latène" (especially in French adjectival forms) or "La-Tène". In German Latènezeit or La-Tène-Zeit equate to "La Tène culture"

- ↑ Megaw, 9-16; Green, 11-17

- ↑ Garrow, Ch 1 and 2

- ↑ Sarunas Milisauskas, European Prehistory: a survey, p. 354

- ↑ Venceslas Kruta, La grande storia dei Celti. La nascita, l'affermazione, la decadenza, (Newton & Compton), Roma, 2003 ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9, a translation of Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire. Des origines à la romanisation et au christianisme, Robert Laffont, Paris, 2000, without the dictionary

- ↑ Cunliffe 1997:66.

- ↑ "Manufatti in ferro di tipo La Tène in area italiana : le potenzialità non sfruttate".

- ↑ McIntosh, 89

- ↑ McIntosh, 89-91

- ↑ McIntosh, 91-92

- ↑ McIntosh, 91-96

- ↑ Megaw, 51

- ↑ Mystery of the Celts Archived 15 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Green, 26

- ↑ Garrow, chapter 2; Laing, chapter 4; Megaw, chapter 6

- ↑ Megaw, 228-244

- ↑ Laing, Chapter 3, especially 41-42

- ↑ Lionel Pearson, "Herodotus on the Source of the Danube", Classical Philology 29.4 (October 1934:328–337).

- ↑ In another place (ii.33.) Herodotus mentions the Ister, which "rising in the country of the Celts, beginning from the city of Pyrene, cuts Europe in half", which would have made it intersect with the Rhone; Pyrene is not mentioned aside from this context.

- ↑ Forster, Peter; Toth, Alfred (2003). "Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100: 9079–9084. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9079F. PMC 166441

. PMID 12837934. doi:10.1073/pnas.1331158100.

. PMID 12837934. doi:10.1073/pnas.1331158100. - ↑ Harding, D. W. The Archaeology of Celtic Art. New York: Routledge, 2007; other schemes of classification are available, indeed more popular; see Vincent Megaw in Garrow

- ↑ Megaw, chapters 2-5; Laing, chapter 3

- ↑ Megaw, 132-133

- ↑ British Museum - The Witham Shield

References

| Iron Age |

|---|

| ↑ Bronze Age |

|

Ancient Near East (1200 BC – 500 BC) India (1200 BC – 200 BC) Europe (1200 BC – 1 BC)

China (600 BC – 200 BC) Korea (400 BC – 400 AD) Japan (100 BC – 300 AD) Philippines (1000 BC – 200 AD) Vietnam (1000 BC – 630 AD) Sub-Saharan Africa (1000 BC – 800 AD) |

|

Axial Age |

| ↓ Ancient history |

| Historiography |

- Garrow, Duncan (ed), Rethinking Celtic Art, 2008, Oxbow Books, ISBN 1842173189, 9781842173183, google books

- Green, Miranda, Celtic Art, Reading the Messages, 1996, The Everyman Art Library, ISBN 0-297-83365-0

- Laing, Lloyd and Jenifer. Art of the Celts, Thames and Hudson, London 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- McIntosh, Jane, Handbook to Life in Prehistoric Europe, 2009, Oxford University Press (USA), ISBN 9780195384765

- Megaw, Ruth and Vincent (2001). Celtic Art. ISBN 0-500-28265-X

Further reading

- Cunliffe, Barry. The Ancient Celts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1997

- Collis, John. The Celts: Origins, Myths, Invention. London: Tempus, 2003.

- Kruta, Venceslas, La grande storia dei Celti. La nascita, l'affermazione, la decadenza, Newton & Compton, Roma, 2003 ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9 (492 pp. - a translation of Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire. Des origines à la romanisation et au christianisme, Robert Laffont, Paris, 2000, without the dictionary)

- James, Simon. The Atlantic Celts. London: British Museum Press, 1999.

- James, Simon & Rigby, Valery. Britain and the Celtic Iron Age. London: British Museum Press, 1997.

- Reginelli Servais Gianna and Béat Arnold, La Tène, un site, un mythe, Hauterive : Laténium - Parc et musée d'archéologie de Neuchâtel, 2007, Cahiers d'archéologie romande de la Bibliothèque historique vaudoise, 3 vols, ISBN 9782940347353

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La Tène culture. |

- Charles Bergengren, Cleveland Institute of Art, 1999: illustrations of La Tène artifacts

- La Tène Archaeological Sites in Romania