Cycloserine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Seromycin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~70% to 90% |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Biological half-life | 10 hrs (normal kidney function) |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

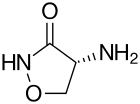

| Synonyms | 4-amino-3-isoxazolidinone |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.626 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C3H6N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 102.092 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cycloserine, sold under the brand name Seromycin, is an antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis. Specifically it is used, along with other antituberculosis medications, for active drug resistant tuberculosis. It is given by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include allergic reactions, seizures, sleepiness, unsteadiness, and numbness. It is not recommended in people who have kidney failure, epilepsy, depression, or are alcoholics. It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe for the baby. Cycloserine is similar in structure to the amino acid d-alanine and works by interfering with the formation of the bacteria's cell wall.[1]

Cycloserine was discovered in 1954 from a type of Streptomyces.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[3] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 29.7 to 51.30 USD per month.[4] In the United States in 2015 the cost was increased to 3,150 USD a month.[5]

Medical uses

Tuberculosis

For the treatment of tuberculosis, cycloserine is classified as a second-line drug, i.e. its use is only considered if one or more first-line drugs cannot be used. Hence, cycloserine is restricted for use only against multiple drug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis. Another reason for limited use of this drug is the neurological side effects it causes, since it is able to penetrate into the central nervous system (CNS) and cause headaches, drowsiness, depression, dizziness, vertigo, confusion, paresthesias, dysarthria, hyperirritability, psychosis, convulsions, and shaking (tremors).[6][7] Overdose of cycloserine may result in paresis, seizures, and coma, while alcohol consumption may increase the risk of seizures.[7] Coadministration of pyridoxine can reduce the incidence of some of these CNS side effects (e.g. convulsions) caused by cycloserine.

Psychiatry

A 2015 Cochrane review found no evidence of benefit in anxiety disorders as of 2015.[8] Another review found preliminary evidence of benefit.[9] Evidence for use in addiction is tentative but also unclear.[10]

Mechanism of action

Cycloserine works as an antibiotic by inhibiting cell-wall biosynthesis in bacteria.[11][12] As a cyclic analogue of D-alanine, cycloserine acts against two crucial enzymes important in the cytosolic stages of peptidoglycan synthesis: alanine racemase (Alr) and D-alanine:D-alanine ligase (Ddl).[12] The first enzyme is a pyridoxal 5'-phosphate-dependent enzyme which converts the L-alanine to the D-alanine form.[12] The second enzyme is involved in joining two of these D-alanine residues together by catalyzing the formation of the ATP-dependent D-alanine-D-alanine dipeptide bond between the resulting D-alanine molecules.[12] If both of these enzymes are inhibited, then D-alanine residues cannot form and previously formed D-alanine molecules cannot be joined together.[12] This effectively leads to inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis.[12]

Chemical properties

Under mildly acidic conditions, cycloserine hydrolyzes to give hydroxylamine and D-serine.[13][14] Cycloserine can be thought of a cyclized version of serine, with an oxidative loss of dihydrogen to form the nitrogen-oxygen bond.

Cycloserine is stable under basic conditions, with the greatest stability at pH = 11.5.[13]

History

The compound was first isolated nearly simultaneously by two teams. Workers at Merck isolated the compound, which they called oxamycin, from a species of Streptomyces.[15] The same team prepared the molecule synthetically.[16] Workers at Eli Lilly isolated the compound from strains of Streptomyces orchidaceus. It was shown to hydrolyze to serine and hydroxylamine.[17]

Economics

In the U.S., the price of cycloserine increased from $500 for 30 pills to $10,800 in 2015 after the Chao Center for Industrial Pharmacy and Contract Manufacturing changed ownership to Rodelis Therapeutics in August 2015.[18]

The price increase was rescinded after the previous owner, the Purdue University Research Foundation, which retained "oversight of the manufacturing operation" intervened and Rodelis returned the drug to an NGO of Purdue University. The foundation now will charge $1,050 for 30 capsules, twice what it charged before". Eli Lilly has been criticised for not ensuring that the philanthropic initiative continued. Due to US antitrust laws however, no company may control the price of a product after it is outlicensed.[5]

Research

There is some experimental evidence to suggest that D-cycloserine aids in learning by helping form stronger neural connections.[19] It has been investigated as an aid to facilitate exposure therapy in people with PTSD and anxiety disorders[20][21] as well as treatment with schizophrenia.[22]

References

- 1 2 "Cycloserine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Gottlieb, David; Shaw, Paul D. (2012). Mechanism of Action. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 41. ISBN 9783642460517.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Cycloserine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Andrew Pollack (21 September 2015). "Big Price Increase for Tuberculosis Drug Is Rescinded". NYT. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Nitsche, Michael; Jaussi, W.; Liebetanz, D.; Lang, N.; Tergau, F.; Paulus, W. (2004). "Consolidation of human motor cortical neuroplasticity by D-cycloserine". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (8): 1573–1578. PMID 15199378. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300517.

- 1 2 "CYCLOSERINE: Human Health Effects". National Institutes of Health.

- ↑ Ori, R; Amos, T; Bergman, H; Soares-Weiser, K; Ipser, JC; Stein, DJ (10 May 2015). "Augmentation of cognitive and behavioural therapies (CBT) with d-cycloserine for anxiety and related disorders.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 5: CD007803. PMID 25957940. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007803.pub2.

- ↑ Schade, S; Paulus, W (12 September 2015). "D-Cycloserine in Neuropsychiatric Diseases: A Systematic Review.". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 19: pyv102. PMC 4851259

. PMID 26364274. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv102.

. PMID 26364274. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv102. - ↑ Myers, KM; Carlezon WA, Jr (1 June 2012). "D-cycloserine effects on extinction of conditioned responses to drug-related cues.". Biological Psychiatry. 71 (11): 947–55. PMC 4001849

. PMID 22579305. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.030.

. PMID 22579305. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.030. - ↑ Lambert, M. P. (1972). "Mechanism of D-cycloserine action: Alanine racemase from Escherichia coli W". Journal of Bacteriology. 110 (3): 978–987. PMC 247518

. PMID 4555420.

. PMID 4555420. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Prosser, Gareth; de Carvalho, Luiz Pedro S. (February 2013). "Kinetic mechanism and inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis d-alanine: D-alanine ligase by the antibiotic d-cycloserine". FEBS Journal. 280 (4): 1150–1166. PMID 23286234. doi:10.1111/febs.12108.

- 1 2 Kaushal, Gagan; Ronaldo Ramirez; Demelash Alambo; Wacharah Taupradist; Krunal Choksi; Cristian Sirbu (October 2011). "Initial characterization of D-cycloserine for future formulation development for anxiety disorders". Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 5 (5): 253–260. PMID 22466372. doi:10.5582/ddt.2011.v5.5.253.

- ↑ Silverman, Richard (1998). "An Aromatization Mechanism of Inactivation of γ-Aminobutyric Acid Aminotransferase for the Antibiotic l-Cycloserine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 120 (10): 2256–2267. doi:10.1021/ja972907b.

- ↑ Kuehl, Frederick A.; Jr; Wolf, Frank J.; Trenner, Nelson R.; Peck, Robert L.; Buhs, Rudolf P.; Putter, Irvin; Ormond, Robert; Lyons, John E.; Chaiet, Louis; Howe, Eugene; Hunnewell, Berl D.; Downing, Geo; Newstead, E.; Folkers, Karl (1955). "D-4-Amino-3-isoxazolidinone, a new antibiotic". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 77: 2344–5. doi:10.1021/ja01613a105.

- ↑ Stammer, Charles H.; Wilson, Andrew N.; Holly, Frederick W.; Folkers, Karl (1955). "Synthesis of D-4-amino-3-isoxazolidinone". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 77: 2346–7. doi:10.1021/ja01613a107.

- ↑ Hidy, Phil H.; Hodge, E. B.; Young, Vernon V.; Harned, Roger L.; Brewer, Glenn A.; Phillips, W. F.; Runge, W. F.; Stavely, Homer E.; Pohland, A.; Boaz, H.; Sullivan, H. R. (1955). "Structure and reactions of cycloserine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 77: 2345–6. doi:10.1021/ja01613a106.

- ↑ ANDREW POLLACK (20 September 2015). "Drug Goes From $13.50 a Tablet to $750, Overnight". Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Learning and Brain Activity Are Boosted by a Dose of a Small-Molecule Compound". Scientific American.

- ↑ Bowers, ME; Ressler, KJ (2015). "An Overview of Translationally Informed Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Animal Models of Pavlovian Fear Conditioning to Human Clinical Trials". Biol. Psychiatry. 78: E15–27. PMID 26238379. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.06.008.

- ↑ Singewald, N; Schmuckermair, C; Whittle, N; Holmes, A; Ressler, KJ (2015). "Pharmacology of cognitive enhancers for exposure-based therapy of fear, anxiety and trauma-related disorders". Pharmacol. Ther. 149: 150–90. PMC 4380664

. PMID 25550231. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.004.

. PMID 25550231. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.004. - ↑ Goff, DC (2012). "D-cycloserine: an evolving role in learning and neuroplasticity in schizophrenia" (PDF). Schizophr Bull. 38: 936–41. PMC 3446239

. PMID 22368237. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbs012.

. PMID 22368237. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbs012.