The Bear (1988 film)

| The Bear | |

|---|---|

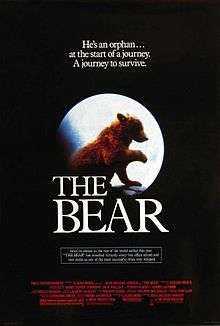

American film poster | |

| Directed by | Jean-Jacques Annaud |

| Produced by | Claude Berri |

| Written by |

Gérard Brach James Oliver Curwood (novel) |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Philippe Sarde |

| Cinematography | Philippe Rousselot |

| Edited by | Noëlle Boisson |

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures |

Release date | 19 October 1988 |

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | English |

| Box office |

$31,753,898 (U.S.) >$100 million (worldwide)[1] |

The Bear (known as L'Ours in its original release) is a 1988 French film directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud and released by TriStar Pictures. Adapted from the novel The Grizzly King (1916) by American author James Oliver Curwood, the screenplay was written by Gérard Brach. Set in late 19th-century British Columbia, Canada, the film tells the story of an orphaned bear cub who befriends an adult male grizzly as hunters pursue them through the wild. Several of the themes explored in the story include orphanhood, peril and protection, and mercy toward and on the behalf of a reformed hunter.

Annaud and Brach began planning the story and production in 1981, although filming did not begin until six years later, due to the director's commitment to another project. The Bear was filmed almost entirely in the Italian and Austrian areas of the Dolomites, with live animals—including Bart the Bear, a trained 9-foot tall Kodiak—present on location. Notable for its almost complete lack of dialogue and its minimal score, the film was nominated for and won numerous international film awards.

Plot

In the mountainous wilds of British Columbia circa 1885, a young grizzly bear cub suffers the accidental death of his mother from a rockslide while digging for honey. Forced to fend for himself, the cub struggles to find food and shelter. Elsewhere in the mountains, a large male grizzly is pursued by two trophy hunters (Jack Wallace and Tcheky Karyo). Although the younger hunter attempts to kill the bear, his shot fails to take the animal down, and the wounded bear flees. Coming across the grizzly a short time later, the cub attempts to befriend him. Uninterested in the cub and distracted by his wound, the adult bear warns the young orphan away with a growl. The cub approaches again, however, and manages to soothingly lick the other bear's wound. A friendship forms between the two bears, and the grizzly takes the orphan under his wing, teaching him to fish and hunt. At night, the cub suffers from nightmares, reliving the tragic death of his mother.

Determined to find the grizzly, the two hunters are joined by a third man (Andre Lacombe) and a pack of hunting Beaucerons. A chase ensues, in which both bears are driven toward a cliff, with the dogs in pursuit. While the cub hides, the grizzly lures the dogs away, killing some of them. He then escapes over the pass with the remaining dogs following behind. The hunters arrive to find their dogs dead or badly injured, one of them being the favorite Airedale Terrier of one of the hunters. Finding the frightened cub, they take him to their camp, where he is tethered to a tree, and tormented by the hunters and their vicious dogs. That night, the hunters plot how to kill the grizzly.

The next day, the hunters separate, with the younger one manning a spot high on a cliff near a waterfall. He descends from his post to wash up in a small waterfall in the hills. His gun out of reach, the hunter suddenly finds himself cornered by the grizzly, who rears and roars at the sight of the man. Faced with certain death, the hunter cowers in fear. The grizzly, seemingly affected by the hunter's distress, turns and leaves. The young hunter, impressed by the bear's act of mercy, attempts to scare him off more quickly by shooting his gun into the air. When the hunter's companion joins him, having heard the gunshots, the younger man tells him that the bear is dead. However, spying the bear ascending a scree, the older man raises his rifle to shoot, only to be stopped by the other man. The three hunters return to their camp empty-handed, where they free the young cub and then ride off into the wilderness.

Alone again, the cub is soon confronted by a cougar, who corners the young bear near a stream. Trying to defend himself against the cougar's attack, the bear struggles to roar. Suddenly, a loud and menacing roar chases the cougar away. Turning, the cub sees the adult grizzly and runs to his side, where he is comforted. As winter approaches, the two bears enter a cave together for hibernation.

Before the end credits a quote by J.O Curtwood comes up saying "The greatest thrill is not to kill but to let live."

Production

Sources

American author James Oliver Curwood's novella The Grizzly King was published in 1916. The story was based on several trips he took to British Columbia, and the young hunter, called Jim in the book, is based on Curwood himself.[2] However, many of its plot elements—mainly dealing with the friendship between the cub and the eponymous grizzly bear—were fabricated. Curwood's biographer, Judith A. Eldridge, believes that the incident in which the hunter is spared by a bear is based on truth, a fact that was later related to Jean-Jacques Annaud. He stated during an interview that he "was given a letter from Curwood's granddaughter revealing that what happened in the story happened to him. He was hunting bear, as he had done often, and lost his rifle down a cliff. Suddenly, a huge bear confronted him and menaced him, but for reasons Curwood could never know, spared his life."[3] Shortly after the book's publication, Curwood—once an adamant hunter—became a supporter of wildlife conservation.[4]

Brach and Annaud decided to set the film in the late 19th century in order to create a perception of true wilderness, especially for the human characters.[5] In addition, while both the bears and the two hunters are named in the script, their names are not mentioned in the film. The bear cub is referred to in the script as Youk, and the adult grizzly is known as Kaar. Tchéky Karyo's character is said to have been called Tom and Jack Wallace's is Bill. These names differ from Curwood's novel; for example, the cub is known as Muskwa in the novel, and his adult companion is called Thor.

Development

After the commercial success of Jean-Jacques Annaud's previous films, including the Academy Award-winning Black and White in Color (1976) and Quest for Fire (1981), producer Claude Berri offered to produce Annaud's next project, no matter the cost.[6] The French filmmaker had first considered the idea of making a film that included mammal communication through behavior, rather than language, while working on Quest for Fire. He became particularly interested in making an animal "the star of a psychological drama", so he "decided to do an entertaining, commercial adventure and psychological film" that would have an animal hero.[7] He discussed this idea with his longtime collaborator, screenwriter Gerard Brach, who within a few days sent Annaud a copy of The Grizzly King, to which the filmmaker quickly agreed.[8]

Although Brach began writing the screenplay in late 1981, Annaud took on another project, that of directing a film adaptation of Umberto Eco's book The Name of the Rose. Between preparing for and filming his next film, Annaud traveled and visited zoos in order to research animal behavior. In an interview he later gave with the American Humane Association, Annaud stated: "Each time I was fascinated with the tigers, to a point that I thought to do a movie called The Tiger instead of The Bear. In those days I felt that the bear, because they're so often vertical, would give me a better identification, or would provide more instant identification from the viewers."[9] The finished script was presented to Berri in early 1983.[10]

Filming

Shot from May 13 to late October 1987, The Bear was filmed almost entirely in the Italian and Austrian areas of the Dolomites. Several additional scenes were also filmed in a Belgian Zoo in early 1988.[11] The crew consisted of 200 individuals. Husband and wife team Tony and Heidi Lüdi served as the film's production designer and art director, respectively, alongside set decorator Bernhard Henrich. In their book, Movie Worlds: Production Design in Film, the Lüdis state that as the film's production designers, they "were constantly faced with the question 'What did you have to do?' To which we answered 'We turned the Alps into British Columbia.'"[11] Cinematographer Philippe Rousselot noted that "the only thing Jean-Jacques was unable to control" while filming in the Bavarian Alps "was the weather: he did not manage to have the clouds take part in pre-production meetings."[12]

While animatronic bears were used for several of the fighting scenes, live animals—including bears, dogs, horses, and honey bees—were used on location for filming.[13] A trained, 9-foot tall Kodiak bear named Bart played the adult grizzly, while a young female bear named Douce ("Sweet" in English) took on the role of the cub, with several alternates.[14] Three trainers worked with Bart (including his owner Doug Seus), eleven with the cubs, three with the dogs, and three with the horses.[13] One day during production, Bart injured Annaud while the two posed for photographers; Annaud's wounds, which included claw-marks on his backside, had to be drained with a shunt for two months.[15] In addition to the real bears, there were animatronic bears which were used in specific scenes that were made by Jim Henson's Creature Shop.

Themes

With its intersecting story lines of animals and humans, The Bear includes a variety of thematic elements. These themes include orphanhood, peril and protection, and mercy toward and on the behalf of a reformed hunter.

Film critic Derek Bousé has made the connection between The Bear and Disney's model of wildlife films, comparing not only the sympathetic characters but also the filmatic structure, to the animated Bambi (1942) and the live-action Perri (1957).[16] In his 2000 book Wildlife Films, Bousé makes a stronger correlation between Annaud's film and Disney's Dumbo (1941), in that both young animals lost their mothers at an early age, creating an unfortunate situation that allows the rest of the plot to develop (although, Dumbo's mother was merely imprisoned for a while, and was re-united with her son at the film's end).[17] Dumbo and The Bear also share a similarly purposed dream sequence, brought on by alcohol in the former and hallucinogenic mushrooms in the latter.[16]

The theme of the reformed hunter is a direct reference to the original novel and its author. James Oliver Curwood, himself a past hunter and trapper, considered The Grizzly King to be a "confession of one who for years hunted and killed before he learned that the wild offered a more thrilling sport than slaughter".[18] During its American release, the film used one of Curwood's famous quotes as a tagline—"The greatest thrill is not to kill but to let live"—and the film was endorsed by both the American Humane Association and the World Wildlife Fund.[19]

Release

The Bear was released on October 19, 1988 in France, and October 27, 1989 in the United States. An official tie-in to the movie, The Odyssey of 'The Bear': The Making of the Film by Jean-Jacques Annaud, a translation from the French edition, followed in November. In addition, Curwood's original novel—out of print in the US for fifty years—was republished by Newmarket Press, and a children's book titled The Bear Storybook was published by St. Martin's Press.[20]

Critical reception

The film was a critical success, holding a 92% "Fresh" rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[21] Some critics pointed to The Bear's adult handling of the wildlife film genre, which is often dismissed as belonging solely to children's films.[22] While positively reviewing the film, critic Roger Ebert wrote that The Bear "is not a cute fantasy in which bears ride tricycles and play house. It is about life in the wild, and it does an impressive job of seeming to show wild bears in their natural habitat" and that scenes from the film, especially those "of horseplay and genuine struggles – gradually build up our sense of the personalities of these animals".[23]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times, however, believing that the film was less about its wild characters and more about personification, wrote: "The Bear...is a remarkable achievement only on its own terms, which happen to be extremely limited and peculiar...its true emphasis is not on wildlife. Instead, it grafts the thoughts and dreams of more commonplace beings onto bear-shaped stand-ins."[24] Writing for the hunting and fishing magazine Field & Stream, editor Cathleen Erring stated that The Bear not only stripped its human characters of "all sympathetic traits and [gave] them to the bears", but it also created "a caricature that will subject anyone embarking on a bear hunt ... to the kind of scorn previously reserved for 'Bambi Butchers'."[25]

Some reviewers were critical of the film's dream sequences, which heavily utilize special effects and deviate from the overall naturalistic feel of the film. In his review for the St. Petersburg Times, Hal Lipper called the dream sequences "existential flights of fancy are accompanied by psychedelic images that seem better suited for '60s 'happenings.'"[26] In addition, one scene in which the adult bear mates with a female bear while the cub looks on was criticized as being unfriendly for children viewers.[24] David Denby of New York Magazine stated as much in his review of the film, noting "I would like to be able to recommend The Bear as a movie that parents and children could see together, but I'm afraid there's a scene in the middle that would have to be... explained."[27]

Awards and nominations

Won:

- 1988: National Academy of Cinema, France, Academy Award (Jean-Jacques Annaud)

- 1989: César, Best Director (Jean-Jacques Annaud)

- 1990: Genesis Award, Feature Film (Foreign)

- 1990: Guild of German Art House Cinemas Film Award, Silver Foreign Film (Ausländischer Film) (Jean-Jacques Annaud)

Nominated:

- 1990: Academy Award, Best Film Editing (Noëlle Boisson)

- 1990: American Society of Cinematographers Award, Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases (Philippe Rousselot)

- 1990: BAFTA Film Award, Best Cinematography (Philippe Rousselot)

- 1990: Young Artist Award, Best Family Motion Picture - Adventure or Cartoon

- César - Best Cinematography (Philippe Rousselot)

- César - Best Film (Jean-Jacques Annaud)

- César - Best Poster (Claude Millet, Christian Blondel, Denise Millet)

- César - Best Sound (Bernard Leroux, Claude Villand, Laurent Quaglio)

Notes

- ↑ Cerone, Daniel. "How to Train an 1,800 Pound Movie Star: What It Takes to Turn a Kodiak Into a Screen Sensation: A Bear's-Eye View of Grizzly Country," Los Angeles Times, Oct. 22, 1989. Online at Latimes.com, retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ Eldridge, p. 7

- ↑ Mahar, p. E01

- ↑ Eldridge, pp. 7–8

- ↑ Thompson, p. 2

- ↑ Benabent-Loiseau, p. 7

- ↑ Nichols, p. 23

- ↑ Benabent-Loiseau, p. 8

- ↑ Milosevic, Yvonne. "Film & TV Unit Profiles: Jean-Jacques Annaud". American Humane Association. Retrieved on 6 June 2012.

- ↑ Benabent-Loiseau, pp. 11–12

- 1 2 Lüdi, p. 72

- ↑ Baron, p. E1

- 1 2 Nichols, p. 26

- ↑ "EL OSO making off (Jean-Jacques Annaud)". YouTube.

- ↑ Schickel, p. 97

- 1 2 Bousé (1990), p. 31

- ↑ Bousé (2000), p. 138

- ↑ Curwood, p. vii

- ↑ Wilson, p. 154

- ↑ McDowell, Edwin. (20 September 1989). "Book Notes". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ "The Bear Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Bousé (1990), p. 30

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. (27 October 1989). "The Bear". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- 1 2 Maslin, Janet. (25 October 1989). "The Bear (1988) Review/Film; Two Bears Who Are Just Plain Folks". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Errig, p. 172

- ↑ Lipper, p. 13

- ↑ Denby, p. 70

References

- Baron, David. (11 November 1989). "The Bear". The Times-Picayune, EE, 3pp.

- Benabent-Loiseau, Josée and Jean-Jacques Annaud. The Odyssey of the Bear: The Making of the Film by Jean-Jacques Annaud. New York: Newmarket Press, 1989.

- Bousé, Derek. (Spring 1990). "Review: The Bear". Film Quarterly, 43(3), pp. 30–34.

- Bousé, Derek. Wildlife Films. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8122-3555-X.

- Curwood, James Oliver. The Grizzly King: A Romance of the Wild. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1916.

- Denby, David. (30 October 1989). "Wild Thing". New York Magazine, p. 70.

- Eldridge, Judith A. James Oliver Curwood: God's Country and the Man. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1993. ISBN 0-87972-604-0.

- Errig, Cathleen. (March 1990). "Books & Comments: The Bear". Field & Stream. 94(11), p. 172.

- Hal, Lipper. (27 October 1989). "The Bear Makes the Beast of it: Tale of Survival is 'Bear'ly There". St. Petersburg Times, p. 12.

- Lüdi, Heidi, Toni Lüdi and Kathinka Schreiber. Movie Worlds: Production Design in Film. Berlin: Edition Axel Menges, 2000. ISBN 3-932565-13-4.

- Maher, Ted. (5 November 1989). "Filmmaker calls 'Bear' Challenging Production". The Oregonian, Lively Arts Fourth, 4pp.

- Nichols, Peter M. Children's Movies: A Critic's Guide to the Best Films Available on Video and DVD. New York: Times Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8050-7198-9.

- Thompson, Ann. (September 1989). "Quest for Fur". Film Comment, 25(5), pp. 2–4.

- Schickel, Richard. (October 1989). "The Bear Review and The Bear Facts". Time, 134(18), p. 97.

- Wilson, Alexander. The Culture of Nature: North American Landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1992.